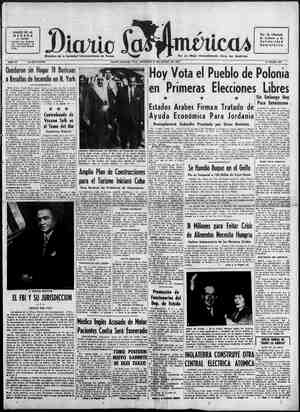

Diario las Américas Newspaper, January 20, 1957, Page 23

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

they cavort around for a while, then the leader of the challenged group tries to identify the oppos- ing leader among the motley cost- med figures under the street light. If. he succeeds, the losers treat his team to a party; but if he fails, his group must stand host. How these jokes have come to be associated with the Christmas cele- bration I do not know, nor do I understand their significance — if any. With Christmas Eve’ or Noche- buena, comes the peak of the sea- son. During the day families are busy with preparations for the evening and with the arrangement of special delicacies known as dul- ces de nochebuena or simply nochebuenos, tradiotional Popayan concoctions artistically arranged on a glass or silver platter. In the center a large triangular cruller stands up like a golden sail, com- pletely surrounded by ring crul- lers, pear-shaped fried sponge cakes called buiiuelos, glistening squares of colored gelatine candy, small containers of blanc mange or ariqupe, -and brilliant-hued eandied figs or orange peels filled with sweet syrup. As each tray is completed a servant delivers it to the home of a close frined with a brief greeting or simply the ‘send- er’s calling. card. For a while, these trays stand in the dining rooms as confectionary tokens of friendship .. but parties and dancing are young people. but as evening approaches, the children are allowed to nibble. Nochebuenos are also served dur- ing the ensuing festivities. On Christmas Eve the streets are deserted until almost ten 0’ clock. Gradually they fill with crowds dressed in their holiday best. People meet in cafés or in friends’ homes to share the holiday spirit before attending midnight ‘Mass. Just before midnight . the streets are empty again, but the many colonial churches are filled to overflowing. The mood is gay, for through the haze of incense that fogs the mellow candlelight the sound of the popular bambucos and pasillos floats over the throng. By tradition, secular musicians who usually play for dances and parties provide this pre-service music. At the stroke of twelve, bells through- out the city ring out rejoicingly, and the Mass celebrates the birth of the Holy Child. At the end of the service, exu- berance seizes the city as the crowds pour into the streets. The bands play the gay music of the folk dances again, the noise of the Chirimias rises above the hum of voices, the stacatto brilliance of fireworks flares in every quarter, the church bells clang deafeningly, and men, women, and children warmly embrace relatives and friends and wish them “Felices Pascuas.” The central plaza fills with celebrants and the cafés do a Tushing business; then the throngs begin to thin out again. This is a time for presents and family dinners. Almost everyone finds his way to a relative’s home, where he joins with cousins and brothers and sisters in the most exciting part of the Christmas ce- lebration. Toys for the children are carefully placed beside the pese- bre, as gifts from the Baby Jesus, Once everything is in order, the little ones are awakened — if in- deed they have slept at all — and everyone watches them open their presents and. whirl in a daze of holiday joy. For at least some of the boys, part of their happiness , arises from relief in finding that . _ SUNDAY, JANUARY 20, 1957 ‘ El Nifio Dios has not left charcoal as punishment for their misdeeds of the past year. Adults, especially relatives, ex- change gifts, if they did not pass them out before going to Mass. After the youngsters have gone to bed, the rest of the family gathers round the table for the Chirstmas feast. In many homes, the main course is a special soup or stew, sancocho, made with chicken or some other delicacy. In the wealth- ier homes the piece de résistance is the traditional Iechén, a whole roast pig stuffed with rice dress- ing and surrounded by cooked fruits that are both decorative and tasty Bowls of salad and fruit and platters of bread and rolls make the rounds. Everyone stuffs him- self, while conversation and laught er .sweep back and forth across the long table There are pitchers of coffee and rich, dark chocolate. Anyone who takes chocolate stirs in generous spoonfuls of fresh white cheese until a froth rises and the liquid becomes thick and creamy. Cakes and buiiuelos, most- ly from the nochebuenos, go with this liquid refreshment. After dinner, the oldsters linger at the table to chat, but the young- er members sing amd dance until the first morning light haloes the mountains. As the party breaks up, frineds part with Christmas wishes. popular too, especially with the The sons and daughters of the house kneel briefly before their parents to receive’ their blessings for the holiday season. Now the streets of Popayan are quiet. Peo- ple hurry homeward, glancing only casually at each other, at the tired Chirimia in front of a bar, or at the occasional revelers whose Christmas spirits have caught up with them in a quiet doorway or on the hard, cold sidewalk. Christmas Day is usually quiet, since the long celebration has left almost everyone exhausted. In some homes the children wake in the morning to find presents from their parents hidden under their beds or in the covers. These usual- ly keep them occupied while the rest of the family sleeps until mid- day or after. Sometimes their nur- ses take them to the edge of town to join the parade of children to the Church of Belén, high on a hilltop. Every Christmas Day youngsters from the surrounding countryside parade with noisemak- ers and balloons up the zig-zag path to the Belén pesebre. In the late afternoon some people go visit ing, others read the Special holiday editions of the newspapers, and sdme of the more opulent attend a club tea dance. The day passes slowly and serenely, except for the occasional sound of a passing Chi- rimia. But Christmas is hot over. Three days later festivities break out again on the Day of the Holy In- nocents to celebrate the eseape of the Holy Family after Herod’s or- der to slaughter all newborn in fants. It is a real April Fool’s Day, with exploding cigars, hoax edi- tions of the newspapers, crazy an- Douncements on the radio, and practical jokes on every hand, When someone is tricked, the per- petrator shouts “Pase por inocem te (The joke’s on you),” and everyone, including the victim, howls with laugter. Adults finish the day with dancing in the bars or @ costume party at a club. January 5 and 6 mark the end of the Christmas season with the nearest approach to a Mardi Gras Popayaén can muster. The fifth ie eee, Street vendors hawk Christmas wares on edge of Popayin market place, the Day of the Black Kings and the sixth is known variously as Day of the White Kings, the Feast of the Magi, or the Epiphany, which commemorates the arrival of the Kings of the Orient to present their gifts to the Christ Child, Pre- viously, this was the regular time for exchanging gifts, rather than . Christmas Day. Even now, the lucky children receive another round of presents. On the Day of the Black Kings little boys decorate their faces with fierce, black-shoe-polish musta- chios and goatees, chase the squeal- ing girls with grimy hands, and casually lay black handprints on innocent passers-by. In the after- noon and evening the bigger boys chase the bigger girls, many peo- ple wear masks and costumes in the streets, and groups ride aréund in trucks singing and throwing confetti and paper serpentinas at pedestrians. The Chirimias add their drums to the noise and there is drinking and dancing in the bars or, in slightly more sedate style, at one of, the three clubs. Next morning the color empha- sis changes from black to white. Instead of using shoe polish, the boys chase the girls with white powder. Decorated trucks and cars filled with young people go through the streets flinging corn- starch or flour on everyone they pass, the Chirimias with their dane ing Diablos make their final ap- pearance of the year, and the aguardiente flows freely through- out the day and on into the even- ing until utter fatigue brings everything to a halt. Not Iong ago the Epiphany ee- lebration was much more closely linked to the Christmas story by colorful parades that featured the magnificently arrayed Kings, fel- lowed by their fantastic retinue, as they traveled to visit the Child. The dramatic, sacred elements of these showy pageants were gra- dualiy submerged under a welter of Jocal political animosities. The parades became unruly mobs that fought as they passed each other, Finally, city authorities banned them, and nothing is left of the Feast of the Magi but mischief drinking, some partying, and poig- nant memories of.a grand carouse, Of course, outside influences have crept into the Popaydn Christmas celebration. Strings of colored lights adorn some pesebres and Santa Claus cutouts, distribut- ed by U. S. or European manu- facturers, are displayed in a few store windows. Christmas trees and Santa Claus made, their first ap- pearance in Popaydn only twelve years ago. In time they will pre- bably be. grafted onto the prevaih ing traditions, although they have met with considerable resistance. For new, Christmas in Popayaén ie still primarily a sacred celebration that, despite the extraneous ele- ments that have becme a part of it, has net been commercialized Chirimias in typical rural costume. Fiber shoulder bags will probably swell with coins at end of day’s musical meandering. Masked “diablo (devil)” dances with Chrimias, ward eff teasing children with a whip, and collects pennies, | oe