Evening Star Newspaper, September 9, 1928, Page 87

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

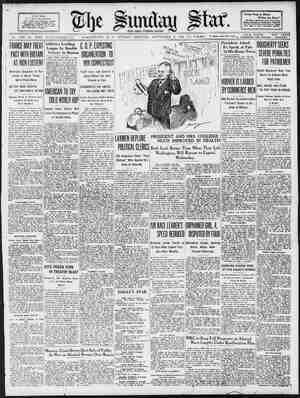

THE SUNDAY STAR. WASHINGTON, D. C., SEPTEMBER 9. 1928—PART T. Master Fisherman Sends Coolidge’s Equipment to Junk Heap BY J. RUSSELL YOUNG. CEDAR ISLAND LODGE, BRULE RIVER, Wis., September 7, 1928. ALVIN COOLIDGE, since coming to the North woods for his va- cation, has developed into a| real fishermzn. No longer i3 the man who waited so. long before he decided o learn how to play a rank amateur with the rod and reel. No longer does he fish merely for fish. He now fishes for the love of the sport itself and for the thrill and excreise it affords him. The President has long since aban- doned the use of angle worms as bait He used them before he started te ac- quire the genuine sportsman's love of fishing. As he Ims :ro:nssed. and grown more skillful, and as his devoticl has become more intense, he aside spoons, and spinners, and all other such devices to coax fish to his lin He has graduated from all that. He 1s now in the class of the fly fisher- | men—dry flies. That is why he o longer is in the bush league of anglers. That is why he is now looked upon as a | T Amons. the experts fn_this sectio Among_the ex tion | (and thgre are many) fly fishing is the real sportsman’s way of taking game | fish from the water, especially dry-fiy fishing. That is recognized as real angling. It is an art in itself. and is considered to be the acme of the sport. It | 1s the ambition of every ardent fly fisher- | man to become proficient in the art of | handling and placing a dry fly. and, ac- | cording to those who have béen watch-| ing the President’s progress .since he | took up this scientific manner of a gling, more -than a month ago, he h: developed remarkably well, and has| demonstrated skill and deftness thai | elevate him to the big league. | Mr. Coolidge has prograssed to njm} int where he can hold his own with | h> best of them. If he is not now actually an expert, he is at lcast on ti threshold of becomiing one. At any rato, he_loves the sport. President Coolidge owes this progress | JOHN LAROQUE, THE PRESIDENT'S CHIPPEWA GUIDE, 1S A BOAT- MAN, NOT A FISHERMAN. 5 tor and companion for the Presi- |t There was no question about his be- |ing the best fisherman in this part of the country. Besides. he is intelli- gent, is versed in woodcraft, knows | the wa lover of ture, Moreover, he has a re| | knowing the Bruls river any one in the head-of-the-lakes | country. He was just the man for the | | PresiGent, with these reservations. | It was thought at first that John | Le Roqus, the half-breed Chippewa Indian, who has been on= of the Brule | ides for many years, would fiil the l. But La Roque is not a fishorman. He is guide and a boatman. He is skilled at handling a canoe, and knows | ths trails and the best fishing holos, | but he is not versed in the finer arts| of fishing. Like all Indians, his 1idea | of fishing is to catch fish to eat. It| makes no difference how you land them ; or what you use to entice them to your | hook. just as long as you catch tnem. Indians are interesting in this re- spect. They are unlike the white man, to the extent that they do not fish for the love of the sport. With them it is a means of providing f They will catch only the fish needed for food at | one time. John La Roque has been helpful to the President only as a boatman and a | guide. As a matter of fact he knew no more about the finer points of angling than did the President—probably not so much. He knew where the fish could b* found and the hours when they would be biting the best, and he has | itation of and this dev:lopment of a real passion George . & veteran Brul to be one of the most expert dry-il fishermen in th> country. dry-fly fishing, and who subsequently taught him and coached him until he now ranks so well as an angler. Babb is not only an expert with the rod and reel, but he is a trapper and rtsman to the core. He has been in| e North woods for more than 40 years. He has trapped and hunted game COL. BILL STARLING OF THE | SECRET SERVICE, A REAL LOV- _ER OF FISHING. through these wilds for decades. He| has worked in lumber camps. He has | seen life in its crudest and hardest form, and as the President’s tutor and trainer he has been no easy task master. Presidents mean nothing to this out- doorsman, and he has made no allow- ances for Mr. Coolidge during the course of his instruction just becausc e | President’s line and guide ana sportsman, who is con ea,u:fl‘:"'l. It was Bab3 | using most any old who first intercsted the President in | casting in any sort of fashion. He was | D been handy at taking them from the ~~ing them in the The President ‘ast floundered along. | thing on his line and | having a good tim~» and was catching plmtygol fish, bui he knew he was not improving his skill and for that reason he was not wholly contented. hesitating about engaging Babb. | fish right, he suggested Babb teacher. tter than | t North woods. | tlon in the Adirondack Mountains Correction—Qutdoor Life Relieves Intensity of Executive Mind. EtrMLS that those intrusted with the | fiching expeditions, and when he dis- | first impre: ponsibility of getting a fishing in- | covered thet the President wasn't going 0 be satisfied until he legrned how to as a Starling previously had been fishing with Babb, and he had occasion | to know there was no mistake about the | latter’s skill. of wild animals and is a|had taken some less dry-fly casting and he was most enthu- siastic when he urged the President to The secret service man ns on the sly m‘ Ty it PR | 'HE President soon formed a strong | attachment for this man of the He has learned much | from him and expects to learn more. He | has found that Bab> is a2 man of strong character and tha: he knows about many things other than dry-fly fishing. This attachment is very similar to the one the President formed on his va o years ago for Osmun Doty, who served then as his guide and outdoors com- panfon. Doty was soft spoken and not talkative and was a trifle awed by being so close to the President. Otherwise these two men who struck’ the fancy of President Coolidge are very much alike, although Babb is by far more expert as a fly fisherman. Dry-fly fishing differs from ordinary wet-fly fishing. The fly, line and leader must float on the surface of the water. | It must be remem d that the trout | les always with he2! up stream. Thus | the fly represen's natural fly or | AVeUsT 1928 ¢ | out >d with Babb. They were nding in front of Cedar Babb was using some oil esident. It had on the be Tsland Lodge. belonging to the been sent to him 2nd was supposed to be the last word in such oils. Babb wanted to use his own concoction, but the President insisted on his. Babb did not argue further, but he was not careful or sparing in his use of the ofl. _He not only applied it overgener- but_he spilled a quantity on the ground. The President waited until he had fimshed and then asked for the can of oil. After scrutinizing it closeiy he remarked, “You overlooked some. How'd that happen?” Later that dav there were more flies |and leaders to he olled. The President |and Babb were in the canoe, far up the Brule. Babb started to us2 his o, but again the President insisted on his own and handed the can to Babb. The President then turnsd his attention to casting, and while his back was turned Babb quickly put the President’s oil aside and substituted his own article. When he had finished the job he re- merked to the President, who all the while had had his back to him and ap- parently had been intent on fishing, that he was finished. ‘Without turning his "eal and con- tinuing his casting as he spoke, the President said, “You are mighty stub- born, aren’t ? T have always been told so, but what makes you think s0?” Dabb asked. “You thought I wouldn't know you other insect floating down the stream, and that intricate knack of making the dry fly imitate the movements of the natural fly or other insect in its efforts to_leave the water is one of the most difficult parts of this scientific form of fishing. To place the fly on the surface of the water is a real art. It must be done in such a manner as to give the | impression that it is a natural insect alighting. The trout is wise and wily. It must be terribly hungry to be easily | fooled. | ‘There is no element of luck in drY—i fly fishing. It is simply the study of n.tre and the habits of fish and knowledge of how to cast properly. There are hundreds of different kinds of flies on the market. The size of the fly used is of greater importance than the kind of fly used, owing to the size of insect life on the water being fished. The fly must be oiled and also the leader to keep th>m afloat on the sur- face. The kind of oil and the method of applying it are all a part or scien- | tific fishing. | Babb makes his own oll. He uses deer fat and olive oil and something els> h> keeps a secret, Sportsmen love to have such secrets. It was in relation to the oiling of Col. E. W. Starling of the secret serv- ice frequently accompanied him on his flies and leaders thai the President was used that oil of yours, but you didn't fool me,” was the President’s dry an- swer. “I saw the reflection of your movements in the water.” Babb admitted his deception, but went on to assure the President that he would be giad of it after he tried the flics he hed oiled. The Presi- dent socn agreed with him and has | since used no cther kind of cil. | * ok % | "THE President was quick to sense the | possibility that Babb could improve on some of the other things in his fishing paraphernalia. Therefore he suggested: “Maybe therc are other things in my outfit you don't approve of or could improve upon,” “I'll say I could!” Babb shouted. “Guess you and I'll have to go through those things when we get back and separate the good from the bad,” Mr. Coolidge annsunced. “That's fine!” shouted Babb. “So far 2s I'm concerned we could start right now.” Th= President’s look of bewilderment caused the woodsman quickly to add that he wouid like to start with the very rod and reel the President was then using. “What's wrong with this?” Mr. Cool- | ed. GEORGE BABB, VETERAN BRULE GUIDE, WHO TAUGHT ;l'\HE PRESIDENT DRY FLY FISH. NG. | PRESIDENT COOLIDGE CAST- ING FOR TROUT. HIS TEACHER IN THE STERN OF THE CANOE. : rather meekly asked as he looked down at the rod in his hand. ‘What's wrong?” Babb fairly bawl- “The whole damn thing is wrong.” “It cost a heap of money; I think is was $19:" Mr, Coolidge retorted with Yyme feeling. “I don’t give a darn if it cost $99. It is no good,” Babb bawled, this time a little louder than before. Seeing that the President wanted to know why his rod and reel were not th> thing to use, Babb went on to ex- plain. When he had finished his dis- sertation, the President, who had listened attentively all the while, simply remarked: “That sounds reasonable. I guess it means my getting the kind you recommend.” When President Coolidge states that a thing sounds reasonable, that is a very good sign that h2 is convinced, or that he is being won over to your way of thinking. Those who have been around him for some time know this. | | Babb was quick to learn it. The Presi- dent has used that phrass many times | since, while Babb was teaching him. ‘The President did get Babb to go through his fishing things that very night. Babb told the President that he never saw so much and such a variety of junk. All sorts of spoons and hooks and other contraptions to lure fish. He culled out what he thought was worth while, and the re- mainder he put in a pile. ‘The President had received ever so many presents in the form of fishin tackle, and purchased some himself. To discard all thes> things, some of them quite costly, just because they were frowned upon by his instructor, did not wholly conform to his ideas of thrift. His New England training re- ceived a terrible jo!t when he2 finally ordered the things thrown into the junk heap. ‘This breaking away from traditions and a training of economical living was proof in itself that Calvin Coolidge healthier. getting more fun out of life, though he still is President. is more jubilant over it all than is Mrs. Coolidge. to play more, to get some kind of a hobby, anything to gst him away from his work and his serious thoughts. M President Becomes Friend of Brule Angler, Who Treats Head of Nation as Firmly as He Would Any Other Pupil Who Needed that the President was terrible when he took him as a pupil. “All he kne about fishing then was to catch fish, Babb explained. “He might just as well have used a shotgun, if that was all_ he wanted.” But Babb thinks differently of him now. He contends that the President possesses all the traits and character- Listics that go towaré —==inz z fisher- he finally had a hobby, and that ms| whole heart was in it. He is deriving | any amount of real pleasure from it. | too. There is not the slightest doubt | that he has had more genuine enjoy- this_Summer, especially since he took on Babb as an instructor and com- panion, than any time since his care- tree days as a youth in the Vermont hills. It seems as though he just can- not get cnough of trout fishing. He has been after bass in a nearby lake once or twice, but his thirst has been ff‘l]r the wily trout—the gamest of them a how to play—to play and like it. He was 56 years old last month, and he basn't done much except wcrk and study since he reached his 20s. Mr. Coolidge is looking stronger and He seems happier. He is even No one She has always wanted him B 6 R. COOLIDGE recently said to this writer that he has discovered that fishing gives him an incentive to get out in the open and to stay there for long periods. It gives him an interest in_bodily exercise and fresh air. President Coolidge is taking his fish- | ing seriously. He has entered upon it | with the customary Coolidge deliberate- it took him a long time to learn | man—patience, persistence ana a quiek eye. He only needed the heart for the sport and more skill. Now he has them all. He showed that he had the heart and love for the svort when he took np dry fly fishing. Further and more posi- tive proo: was furnished when he start- ed fishing at night. That's the real sport. That is when one gets the big thrill out of the sport. The large trout lie in deep, secluded spots during the day and they are hard to coax out into the open, much less upon your hook. At evening time they move into shallow water to feed, as it is easier to obtain food in shallow water. For this reason few large trout are caught during the middle of the day The Bruie Kiver guides ars a ple- turesque and interesting lot of men. The majority of them are Chipptwa Indians who have been born and raised in this romantic country, but the ~vhi'- guides are invariably better fishem and are better able to tell about the Brule country itself. It is a healthy and fascinating means of livelihood, though associated with some little hard- ship and occasional perils. First of all, a guide is supposed to know his section of the country. He must be able to cook good meals. He must know how to paddle and pole a canoe and have strength enough to carry it over a portage, of which there are several on the Brule throughout its length. He must know the channels and the rocks as well as the fishing holes and where the best camping sites ness. That is his way of doing things. FISHING DOES NOT APPEAL TO JOHN COOLIDG AROUND THE SUMMER WHITE FOR HIS SAXOPHONE PRACTICE. are along the way. He must know how ND WOODS HOUSE SEEM A FITTING PLACE That is the reason he wanted to learn how to fish right and to become really Fmflcient. He fished a great deal dur- ng his stay in the Black Hills last Sum- mer and while traveling through Yel- lowstone Park, and caught his share of fish. He fished during the Summer be- fore that up in the Adirondacks. It was there that he first went in for the sport since becoming a man. But he gave little thought to the science associated with the sport until lately. was at last wild about fishing—that Babb has no hesitancy in saying now BY SAMUEL S. DRURY, Headmaser, St. Paul's School, Concord, N. H. O you not recall the sounds and _smells of now that September's and the great bell rings all? Is any memory as ward to its ci 1 days vivid as our first school | t see yourself 20, 30, 40 years iz:‘ e hld of 6, trudging to_the primary schbol, ?‘osnbly with a slne‘ th your arm? ! m’;“:\:ly 1’mpressxve is the thought that | one person out of every five in these | United States this week will ing to the great school bell. Mor: 20,000,000 will answer its call. the toddlers in the kindergarten to the research students in the laboratory, a fifth of the population will be intent on getting and adding to an education. No country pays more, talks more about, thinks it cares more for schools than our country. It is devoutly to be hoped that we are getting our money's | worth, that we are reaping the fruits of r sacrifice, that the September school ggll is summoning its 20 millions to an offering which this year will richer than ever before. The country is vibrant with educa- tional ambition. Hard-working parents. themselves without schooling, insist upon it as a panacea for their sons. More than a million young men and women will be headed this month for the bachelor degree. The country is thick with learners Unexpectedly you see them. Last week an emergency took me to a tiny island | on the coast of Maine. As the motor boat chugged back in the evening, I looked at the young sailor who conduct- ed me, a fine, alert head. delicate fe: tures, bronzed skin. What a | thought I mn my citified sophistication, | that this fine boy is doomed to buXet | with the waves and set lobster pots all | he happened to be in his exalted posi- tion. Winter through. So I essayed, “What | be | pity, | sights and | o school | come | md‘ the children scamper school- | ? ‘Can| 20 Million U. S. Vacations From School Are Ending had trouble with English compositions,” with the unspoken reflection, “and just look \n{hnt a thundering success I am today!” or the mother who sadly con- fesses, “I never could spell.” is layinz a wet blanket on the receptive mind of Y hereb, ereby a disposition is bel in- jured. All education, as Rurunglones has reminded us, is building up a dis- position, and any transmitted sense of inherited deficlency pulls down the thing we are trying to build. The unspoken pressure of parents on children is almost terrifying in its in- fluence. Beginning with the nursery floor, the job of education is to build up in the child a disposition of calm and cheerfulness and love, not of fear and fretfulness and failure. Even if we are not good at certain things, it is our privilege to look hopefully forward, and we may all expect our children to be better men than we are. The whole family must generate a corporate will to do well. It is the first essential. S HE child who must look to the teacher or the school for all his in- tellectual impetus is handicapped. Our second unexpressed aid to progress is an atmosphere of a?preclnnon at home. It the very walls of our houses vocally express what tastes a family possesses, how much more will the avocation of the elders set its tone! Don't you think it must be pretty hard for a child to develop a taste for books and a desire | for book learning when the reading of the family is nothing more solid than flimsy magazines? One thing every family can do—en- courage reading aloud. There you have a pleasurable exercise in brain stretch- ing. Not only shall this be reading to the children, but the children shall read to the family. Select a good, exciting historical novel and have It read aloud, chapter by chap- ter, by Billy and Edith and Tom. Some- times the youngest child reads best of all—that will stimulate the others to to shoot the fa'ls and rapids. of which there are any number on the Brule. Andt a guide is expected to be intelli- gent. e 'O write about the President’s Sum- mer of fishing on the Brule and about the capabilities of George Babb, his instructor, it is highly essential to say something about the Brule River itself. To a lover of a picturesque, wild stream in a country that has all the appearance of being primitive, this river is in a class by itself. It is ap- pealing, not because it is reputed to rank as one of the best trout streams in the United States, nor yet because of the fact that two Presidents have fished on it—Coolidge and Cleveland— but because of its interesting history. There is a charm about this stream. Aside from its real beauty and wild at- tractiveness, it has an intriguing his- tory reaching far back into the past, when the white man first dared this wilderness. Credit is given to Sieur Daniel de Greysolon du L'hut, a French explorer and gentleman ad- venturer and trader, in whose honor the city of Duluth was named, for discovering the Brule. almost 250 years ago. French translation of the Indian name { the river, meaning burnt wood. Du L'hut was in search of a waterway from Lake Superior to the Gulf of Mexico when he entered the Brule. He had little to guide him save what seemed to be fanciful tales of his Chippewa companions, but he traveled the stream from its mouth to its head, a few miles north of St. Croix River, which flows |into the Mississippi. By means of a portage of not quite six miles this river became the connecting ling between the Northwest and the Gulf of Mexico. In this way it figured prominently in the carrying of commerce, especially during that romantic period of the coureurs de bois, and later during the early days of the fur traders. The Brule ran through the heart of the Chippewa country and it has been the witness to many conflicts between the Chippewas and their enemy, the Sioux. About 80 years ago these rivals fought their last’ and probably most terrific battle on the Brule, and ac- counts of that conflict speak of the stream as “running red with Indian blood” on that occasion. There are cabins and claborate Sum- mer camps along the banks of the Brule now, but for the most part throughout its length it traverses a sec- tion that is virtually a wilderness in its virgin and primitive state. When one is canoeing along the stream it is not difficult to imagine being many miles removed from civilization. All is so still. It is just the sort of background that causes one to expect to see the | 2 Mr. Coolidge rather liked this attitude | dO_.YOfl do in the Winter? o e T T ST on Babb's part. ‘The loud-voiced, dic-| GO to school.” was the reply. tatorial master of the art of dry-fiv| fishing made a decided hit with him. | Babb is not easily awed, nor is he afraid to speak his mind. He has never | horitated to tell the President when he was_doing the wrong thing, and he would tell him in a tons that could be heard some distance down the gtream. Sometimes Babb would “bawl ~out his corrections. * %k % T first the what embarrassed by his in- structor, especially when he latter in- jected a few well-chosen cuss words to make his meaning more impressive. He was quick, however, to discover that Babb knew his business. and that he was a real artist in casting and all the other things that go to make an expert angler. He, therefore, was perfectly willing to put aside his presi- dential and personal dignity and be corracted, éven in loud tones. He even ehuckled over Babb's “bawling™ but he drew the line on the latter's ex- travagant use of cuss words. Of course, while talking intently, he thoughtlessly lets drop a cuss word now and then, from force of habit, but, otherwise, the President hds im- pressed him sufficiently to make a change Mvg Coolidge was compelled to laugh outright once. after admonishing Babb. ~hen the latter asked his pardon. said he was sorry. and then remarked in a dejected manner. “whin a big trout the after vou think . ‘gosh.’ or ‘oh! mercy.’ or ‘Heavens' falls so far short @f exnressing vour feelings RBabb is also noted for his loquacity 1t was because of these well-established President was some- | “Where?" said I. He mentionsd a well accredited col- e, r7“whnl are you going to stud, He ruminated in the gloom. | see. I'll be a junior. I'll he | analytical geometry. English literature, ! economics and physical chemistry.” How's that! Things are not, and people are not, always what they seem! | Just as we hear of V. C.'s peeling potas toes in the galleys of ocean liners, so the bellboy in a Summer hotel may | le the Intellectual superfor of those rml | whom he waits. 1 “Look out.” I have warned easy-going { youths: “behind the brass buttons of the boy who jumps to open the door for you mav lurk the coveted Phi Beta Kappa key!" i ES, the country is chock full of learners, and this week the bell will summon many from leisure of sea- shore and mountain to blackboard and freshly varnished desks. There is a tonic in the call. We are glad to go back. Enough of vacation! The school bell is ringing us in! Youth gets demoralized by too much idle time. It takes a well disciplined character to handle prolonged freedom | usefully, or even sweet temperedly. For the last fortnight fathers and mothers undoubtedly have been saying: “It's { high time that John. or Jane. or Doro- thy. or Timothy. got back to school * And the young people know it, too. though they cling to last_days, packing rach day with delights. They know it's time to go to work. and, despite their ‘nmv»smunnx. the normal boy and the | normal girl will be glid when the bell IN THE DAYS OF “READIN’ , 'RITIN' AND "RITHMETIC". irings and they return to fresh text | books. regularity, orderly comradeship. | and the expected decorums of a modern | school. the bell. A cynic has remarked that holidays are devised to give teachers a rest and that terms are arranged to give parents a rest! So now, has your rest begun? Alas, by no means! hard to steer children in the holidays, and now, upheld by the work-a-day week, | the parent must go on steering and con- trolling. Scheduled days are easier for all concerned than days of | uncharted freedom. Term time is trig- ger time than August or July. We | parents, however, have our part in the school. and if we don't play it. how | ever new the equipment. however ex- | pert the teacher. however alert the | ehifld, something will go wrong. Are we sorry for ourselves now that September's come and the bell s ring- ing our children in to school? Parents The parents, I know, are glad to heur | It is | surely | | are a somewhat pathetic lot. We mean 80 well, we're so intense in sacrificial ambition for our young: yet somehow we | don't co-operate effectively in the scho- lastic quadrilateral — the community, | parents, teachers and pupils. There is the parent who mistakes iter- ation for inspiration. “I write to m: boy every day, urging him to do wel says a mother about her boy at board- ing school. Could anything be more surely ineffective? 3 “I ask my boy every morning at breakfast how he’s getting on,” says a | dogged fathor. Could any question be- come more callousing? “I tell my daughter every week that | if she docsn't bring home a good report | we'll have to take her out of school,” says a worrisome mother. U LL these conscientious elders think that a merely stated precept is in iteelf a tonic, Othpr parents wash their hands of responsibflity. “I give my boy to the community to be taught. I don't interfere. I provide him with the time to do what his teachers require, It's up to him, and it's up to them, to make a go of it.” Such a man, by his very negativeness, drags on the pregress of the school. Some fathers and mothers can keep up with their children’s studies and by the evening lamp can actually solve problems_involving unknown quantities or give hinting lifts through complex passages in Cicero. Such family life is rare. We parents may be intelligent and high minded, but the technique of exact scholarship has somehow flown away. What, then, can we do to abet the teacher and speed on the children now that September’'s come? Nagging is no good. Threatening is of little use. An anxious melancholy disappointment seldom acts as a spur to self-centered adolescence. How can we, then, be propulsive factors in the schooling of the child? I suggest that we surround the boy or girl with these three great helps—a spirit of accomplishment, a sense of ?_pprecxunon and a rigid rule of applica- ion. A family can awaken a child’s ambi- tion by corporate, friendly expectation. Careless as boys and girls may be, they all have family pride; they don’t want to let the family down. If the home enerates a vital atmosphere of succesz, fhe child wil catch it, and if praise for | Tais attainment, however slight, is bestowed five times as often as blame for mis- takes, however bad, the child, imma- ture, ignorant, timid and self-conscious as many children are, will develop an expectation to attain which gathers mo- mentum and confidence year by year, Family spirit can be a mighty force 10 the progress of each of its members. ‘The tonic of accomplishment can be- | itsel: come a family tradition. But the father ywho airily declares, “I never could \Afleuund algebra,” or “I always improve. The plot thickens, the excite- ment of the story creates a power to read faster. There will be laughs and gasps, and the great discovery that a book can con'ain life will once for all be made. Poetry, too, will become a pleasure. The reading aloud of such a graphic piece as Masefield’s “Dauber” will convince young people that often very appealing things are couched in verse. And what will be the result? Not only history and language, but the general background of culture, will be- come living realities. School work will thus take on a valid pleasure. The learner will enjoy his task, which is another essential in the gllvine drudgery of getting an educa- jon. Elders can also help by using every opportunity to link learning with living. Unless the learner can discern some connection between today’s lessons and tomorrow's duty, between this year's curriculum and an ultimate career, schooling will be a treadmill affair. But 1f parents can forge a link between the lessons-to-be-learned and the life-to-be- lived, rationality immediately invests the assignments in the books. This is hard. is sometimes frustrated by meticu- lous teachers, whose vision does not ex- tend beyond the schoolroom walls. It is better to chat with your boy and lead him to see the relation between algebra and engineering than to exult when he gets a 90 on his report; it is better to let your daughter's mind leap from the history book to the current newspaper history that every day shapes f between Europe and America than around the bend ahead, manned by a painted redskin or by some dark- skinned, fur-wrapped coureur de bois or by a stern-looking fur trader. It is a beautiful stream. It is hardly wide and deep enough to be called a river. At times its waters are as still as a pond, and upon the surface the trees and growth on the shores are re- flected as though by a huge mirror. Then a little distance ahead the water takes on speed. A series of rapids and finally falls follow. And so it runs its length for nearly 40 miles to Lake Su- perior. There are wild animals in the wilderness on each side of the Brule— deer, black bears, otters, foxes and some wildcats and wolves. The moose has long since disappeared. Along the shore lines there are many b. ver villages and countless muskrat and mink holes. There is considerable bird life, and it is doubtful if the hermit thrush sings more earnestly or sweetly than he does along this ploturesque stream. Tallow Trees. IN Texas from time to time ‘experi- ments have been made to_cultivate the Japanese tallow free. This tree bears nuts that contain a rich tallow- like oil that has been found very valu- able in the manufacture of high-grade vl{nhhex and other much-needed prod- uets. The climatic and soil conditions in that section of Texas are apparentlsi well adapted to the growth of this curious tree, and the experimental gar- to dwell on her puncfuality and deco- rum. Parents hel) efr children best by praise and practicajity. dens have been supplying farmers through that region with young trees with which to experiment.