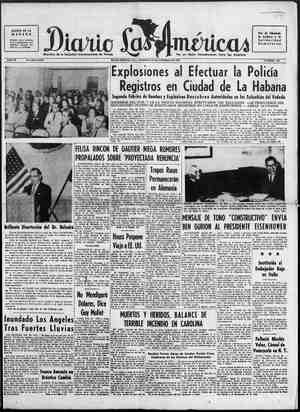

Diario las Américas Newspaper, February 24, 1957, Page 24

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

By HECTOR VELARDE THE GEOGRAPHY, the history, the culture of the American nations show a tremendous variety of in- tensely individual characteristics, ef forms and colors. But nowhere are the differences and similarities more striking than in architecture. Perhaps they can best be studied by observing the various ways in which these countries have assimil- ated or adapted contemporary architecture, in itself rational, functional, and supremely interna- tional. For example, the admirable mo- dern architecture of Brazil was a brilliant and unusually creative outburst, substantially free of tra- ditional fetters of form — colorful, neat and virgin. In México, the pro- eess was different: a violent rup- ture with the colonial past and a more or less explicit, but always intense, seizing hold of indigenous roots — a more complex architect- ure. Now, what has happened in Li- ma, Peri? We can see the impact of the new architecture best in the field ef house building, in which the process is always flexible, in- timate, and, above all, freer of fin- ancial obstacles. What was the traditional Lima house like? Colonial Lima streets were unmistakable. The traveler’s first impression was that he was in some Moslem city. This Arabic at- mosphere was engendered by the co and variety of wooden alconies hanBing over the street like cages and enclosed like closets, echoes of Cairo. Many elements had a hand in transporting this Isla- mic baycony to America: the mild, rainless climate, so like that of Egypt; the heat and dryness of the coastal lands, so reminiscent of North Africa; the first settlers, who were mainly from the Moorish parts of Spain, Estremadura and Andalusia. Looking at the streets more carefully, the visitor would note the Spanish doorways, high and decorative; the barred win- dows, low and protruding, adorn- ed with flower-pots from Seville; and the massive background of thick adobe walls, seemingly sprouted from the Indians’ native soil. The houses, generally two stor- ies high with plain, asymmetrical facades, touched one another, forming, as it were ,a single ado- be wall, varying in height and di- vided by isglated arrangements of doorways, gratings, and balconies. The outside walls were tinted over plaster in warm, bright tones: in- digo blue, yellow, ochre, and a deep rose like the “rose of Lima.” The doorways of the sixteenth eentury were sober in their plateresque or Herreran lines. Those of the seventeenth were of a compact baroque, sometimes very luxurious but always strongly uni- fied in bold relief. The eighteenth saw beautiful entrances given vast and elegant undulations under chu- rrigueresque and, later, French influence, when the arched, rather than rectangular, opening appear- ed. Stone porches were rare; they adorned only a few palaces. Often porches were solidly built of brick, in neat moldings and reliefs, but the usual thing was to make them of adobe, shaping the edges and projections with mud by hand as one models clay. This direct techni- que of shaping forms, and the plasticity of the material, gave Li- ma’s doorways a feeling of latent life, and there was a special charm in the general proportions of mas- ses and the heavy projections of cornices, ornamental brackets, and volutes. The history of Lima architecture could be indexed by its balconies. Those of the sixteenth and seven- teenth centuries are made of small Colonial building on Matavilela Street shows unity between Spanish wooden elements and heavy walls, Reprinted from AMERICAS, monthly magazine published by the Pan English, guese. American Union ia Spanish and Portu- rectangular panels, combined in varied and subtle Moorish designs, with an upper fretwork of small balusters. Those of the first half of the eighteenth century generally have wider, curved lower panels, often developed as a frieze between two bands of small panels. Later in the century the balconies became Gallicized, with Louis XV panels center medallions, garlanded bord- ers, and graceful oval openings. At the end of the eighteenth century, the balcony acquired a classical Took that lasted down to the early nineteenth century and the first years of the Republic: it had small Corinthian or Ionic pilasters, open- ings in the shape of Roman arches with carved spokes, and Greco-Ro- man cornices supported by denti- eles and brackets. The balcony it- self remained the same, repeated through three centuries as a living part of Lima architecture; only the decoration changed with the spirit of each era. Most of the interior floor plans were worked out along a longitud- inal axis with an arrangement simi- lar to that of Greco-Roman houses. These were plans that had a long Mediterranean _tradition behind them, stemming from remote Latin forms passed along through Spain. The odd thing is that in Spain itself the floor plans are not as faithful to this tradition as in the old man- sions of Lima. Just inside the doorway was the vestibule, an intermediate area be- tween street and patio that also gave access to the front rooms, known as “grated windows.” This entrance hall ended in a low arch, supported by heavy pilasters, se- parating it from the patio. This arch was one of the most repeated and characteristic motifs of Lima architecture. The patio, which was always rec- tangular, had rows of rooms — parlors of bedrooms — on one or both sides. Running across the back of the larger houses was a big reception room corresponding to the tablinum off the atrium in the Greco-Roman floor plans. The side rooms usually, the main one almost always, gave direct access to the patio through an arcade lined with fine wood columns; this was the peristyle. Generally the most luxur- ious carpentry is found in the carved brackets and beams of the entrance-hall ceiling, and in the tyipceal forked capitals. The gravel- ed floor of the patio was divided into sections by a central path and side branches paved with marble or flagstone. Pots of flowers and other plants adorned these open, yet intimate, settings. As to building materials, first. of all there was adobe — the same earth and the same walls as on the age-old Indian buildings along the coast. The thick adobe walls gave the house its fundamental struct- ure. On the second story the parti- tions were made of quincha, thin single or double wooden walls fur- red with cane and plastered with mud. Beams supported flat board roofs topped with a thick layer of mud to absorb humidity and keep out heat. This was an architecture of contrast — contrast between the massive, sober, and pompous char- acter of the clay and the delicate, fragile, and luxurious quality of the wood — an organic, plastic, and co- lorful architecture. In rejecting peninsular domina- tion, the independence movement also rejected this architecture re- miniscent of Spain, without realiz ing that by now it had become Peruvian. Moreover, the rejection revealed ignorance of what true Spanish architecture was. So the first “republican” buildings were erected. The native techniques of adobe and quincha gave body to, graceful facades with fluted pilast- ers, Roman Doric capitals, and bal- conies with a series of round arches and perfect Ionic and Corinthian cornices. The patios took on some- thing of the aspect of the peristyles of republican Rome. Symmetry rul- ed all this academic design. But basically these changes were mere- Ty ornamental .The traditional Li- ma house, with its colonial floor plan, balconies, and grated win- _ could not give way so quick- ly. Neocolonial house designed by Rafael Marquina around respect traditional motifs in doorway, walls, balcony. Play of masses and suggestive use of iron bars make a modern 1925 house by Santiago Agurto Calvo fit the setting. Toward the middle of the second half of the nineteenth century French academic neoclassicism blossomed in Lima. Some French and Italian architects: appeared on the scene. There were no native architects. Indeed, engineers were the people considered qual'fied to practice architecture. The tradition- al entrance halls and patios went out of style. On the facades, as on a theatrical drop curtain, adobe, quincha, and paint imitated per- fect stonework, with fine outlined Greco-Roman motifs and project- ing cornices for protection from imaginary rains. The first orna- mental roofs made their appear- ance: tile roofs with fancy gutters, false dormer windows, crestings, and even fake lightning rods. After 1870 (the time of the Fran- co-Prussian War), the neoclassical influence of Italian artists left its mark on our buildings. Then the war with Chile paralyzed all archi- tecturally significant construction until the turn of the century, when a renaissance occurred. This was an era of truly extraordinary eclectic- ism, an era of bad taste that free. ly mixed the “funeral pomp of clas: sical architecture” with the “art nouveau” of 1900. The small man- In the early years of the Republic, neoclassical details replaced Spanish touches in the woodwork and door openings, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 24, 198