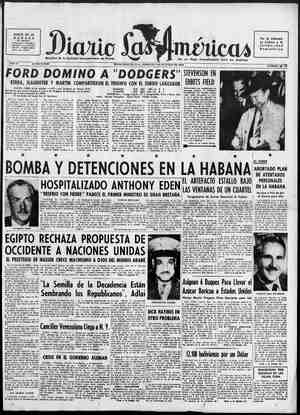

Diario las Américas Newspaper, October 7, 1956, Page 23

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

g Dut a holiday. it is too cold or, more often, ‘too hot; reliable food and decent lodgings are not easy to find; the means of travel are frequently rudimentary, “But we owe a lot to the United States,” remarked Miss Aretz. “Almost everywhere you go now there’s a store with a_modere refrigerator and clean soft drinks.” When the road stops, the folklorist does not; he takes to the trails — conscious, of course, that the harder the bet- ter. professionally speaking. “From that point of view,” said Ramon y Rivera, “It was too bad that in 19- 50 I was able to take a bus over a modern highway to an Argentine village that Isabel had had to visit on muleback before we were mar- ried.” nthe past, financial help being out of the beginner’s reach, the Ra- mon y Riveras did their share of Jbushwhacking without any of the portable comforts, or the vehicle to > earry them in-that could alleviate some hardships. “Most universities and research institutions are hard uv,” explained Miss Aretz. “Before you can get support you have to show them that you can achieve results without it.’ Nowadays, as established authorities, they find the way smoothed for them to an extent — to the considerable ex- tent, that is, that a jeep is an im- provement over a mule. In Ve- nezuela, for instance, they can use the facilities of the Ministry of Education to which the Institute of Folklore belongs. Once, while, ex- ploring the interior of Falcén State in a Ministry jeep, they learned guerite d Harcourt, a contemporary French composer who with her an- thropologist husband had made a study of mca music; Palma had noticed that many of his pupil’s themes employed the pentatonic scale, characteristic of the Andean regions. It then occurred to her that once she had mastered the European forms of musit, she ought to learn something about those of her native continent. At this point her mother suggested that she attend a lecture by the distinguished musicologist Carlos Vega. She became a student of his, and from her composer’s curiosity about folkloric music arose a pas- sion for’ research. Though Miss Aretz abandoned composition and the piano as a formal career, she has maintained her intérest in them. Her own com- positions, she says, are ‘modern with an American feeling, influenc- and rush out in tears.” Fortunate- ed by the music of the countries i know best: Argentina (1 particular- ly like the Araucanian), Bolivia and Pert (with their pentatonic scale), and Venezuela, my second . homeland.” As a composer, she finds that Indian music is closer to modern music, and therefore more compatible, than the Europ- ean-based types properly described as folkloric, “with their series of systems, harmony, rhythm, and so on, which rob me of freedom “of creation.” Her recent works include a two-part ballet called El Liama- do de la Tierra (The Call of the Earth), with an Argentine setting; Three Negro Preludes for piano, Paulo Hidalgo, harpist. and Pedro Nieves, singer and maraca- player, attract admirers at village restaurant in Venezuelan coastal state of Miranda. how a-party like theirs might im- press the impartial observer. The jeep had a loud-speaker.on top and a record-player within, which they used to power the tape-record- er, and was loaded down with equipment. Miss Aretz wore prac- tical black slacks and shirt, and her fair hair — a aovelty in those parts — streamed in the breeze. At dusk, exhausted and grimy, they pulled up in a village. Almost immediate- ly a crowd gathered. “We were certainly not worth looking at, and we couldn’t understand the excite- ment till a child piped up: ‘Where’s the tightrope going to be?” This is not quite the career that Isabel Aretz had in mind when, a determined eight-year-old in Bue- nos Aires, she brought her prim- ary-school music teacher home one day and announced: “I want to learn to play the piano. Her par- ents were delighted as an instance of positive behavior,- this was clearly preferable to her stand- ard practice during the hated vis- its to her mother’s friends which was “to clap my hat on my head ly, the music teacher was an excel- lent: one. : The Aretzes were musical. Both parents were amateur pianists, and Isabel’s mother had for several years been taking the child to con- certs and recitals. She had also showed her how to play by ear. Years later, it was again her in- fluence that was decisive. By that time, Isabel was studying at the Na- tional Conservatory in Buenos Ai- res, intending to become a con- cert pianist. She was also enrolled in a composition class — writing “in the style of,” like most begin- ners, One day her professor, Athos Palma, gave her a book by Mar- SUNDAY, OCTOBER 7, 1956 inspired by Venezuelan songs and dances but not using actual native themes; and Soneto de la Fe en Cristo (Sonnet on Faith in Christ), based on a poem by the Venezuel- an Manuel Felipe Rugeles. Miss Aretz’s travels have taken her to all the South American countries, and she has worked in all but Brazil, Ecuador, and Co- lombia. Among her many publish- ed works are Musica Tradicional Argentina (University of Tucuman 1946), which contains almost eight hundred melodies; and Costumbres Tradicionales Argentinas (1954). In explaining the scope of the lat- ter, she also\defines the scope of the latter, she also defines the scope of her professional activities; she describes only those customs—such as festivals— connected with mus- ie and dancing, her specialty, and limits herself further to the cus- toms of the criollo (native white) and incorporated-Indian segments of the population. The rites and festivals of unassimilated Indians are excluded as belonging to the province of the ethnographer. , While working as assistant to Carlos Vega at the Studio of Music- ology, of which he was director, Miss Aretz was given the assign- ment of “orienting” a young, large- ly self-taught Venezuelan, who was to become her husband. Luis Felipe Ramon y Rivera, born in the small mountain city of San Cristobal, capital of Tachira State, in 1913, had. a legitimate claim to an in- terest in music: his grandfather and The Ramon y Riveras were mar- ried in Venezuela in 1946 and his uncle were music teachers in San Cristébal, and his grandfather’s house was one of the first in town to boast a piano, an expensive lux- ury that had to be brought in on muleback. As a chal, Rawever, he would only practice the vielin un- der the usual compulsion.,From the age of 14, when his father fell ill, Luis Felipe was on his own. He had to work his way through secondary school. The family enthusiasm for music awoke and somehow he scraped together the money to continue his violin studies at the Caracas Academy of Music. Event- ually he became first violist of the Venezuelan Symphony Orchestra. Through his taste for history and sociology he had been drawn to folklore. He read voraciously on his own. When he went to study har- mony and composition in Montevi- deo and Buenos: Aires, he decided to systematize his learning with a course in folklore under Vega and Augusto Raul Cortazar. promptly took off on a series of re- search trips that-lasted a year. An- other two years — 1950-52 — were devoted to--travel in Argentina, Christmas 1954, was spent in the remote Venezuelan town of Pre- gonero, collecting data on elabor- ate celebrations that will probably not withstand for much longer the effects of a road built ten years ago. This journey was made in line with the Institute of Folklore’s pro- gram of hastening at least prestud- ied. At this writing, if their ef- forts have beén successful they have vanished from Caracas again, pursued by the specter of progress. A very short time can make all the difference, once a community has been exposed to change. Some- times only the village ancients have been keeping a bit of tradition alive. The Ramon y y Riveras re- member an aged woman who, dis- cussing with her two or three. sur- viving contemporaries whether to continue honoring the local patron saint in the old way, as they had pledged to do in their youth, set- tled the matter with “a promise is a promise.” But when these people die the custom dies with them “We went to Cupira — that’s a pretty little town on the Venezuelan coast ~— on the advice of Miguel Acosta Saignes, a prominent anthropo- logist. He had seen the St. John’s Day celebration two years before and found it interesting. and au- thentic. But by the time we arrive ed, most of the old-timers were dead and the Church had taken over. When that happens, some of the ceremonies are thrown out as pagan and more orthodox ones are substituted. Or the priest will get: grandiose ideas of improving the festival — importing a band from another village, and so on. This is very common nowadays.” 4 To the folklorist, a good festival is a golden opportunity: music, dances, beliefs. all unfold before him. To the people of the interior, it is only the natural thing to do: “Ask, and it shall be given you,” they believe, and so they wll go to-any lengths to honor the God or the patron saint who thus provides for them. Miss Aretz re- ealls arriving at a village in La Rioja Province, Argentina, while a small pox epidemie was raging. She had_ had a vaccination before leav- ing Buenos Aires, but when a team of government vaccinators came through, she had another. The vil- lagers flatly refused to submti. “After all,” they argued, when she asked them why, “what is God for Among the Indians, some of the very instruments used in cere- monies are sacred. The Ramén y Riveras like to collect native mu- sical instruments, but their own- ers are often horrified at the idea of selling them. On occasion, if they feel friendly enough, they will give them away. Depending, as it does, so largely on the individual, thé study of folk- lore is less a science than an art, in Ramon y Rivera’s opinion. The folklorist must apply a scientist’s rigor to his data, but it is his know- ledge, his integrity, and his skill at interpretation on which he stands or falls. Ramén y Rivera cites three kinds of investigators who only hamper the profession. The self-assured amateur thinks all he needs is to have been born in a given place, to have attended its festivals, to be qualified to expound on the meaning, the origin, and even the causes of a piece of its folklore. The halftrained type is even more dangerous sometimes reliable, sometimes not, he can be neither believed nor discounted. The overenthusiastic investigator (“forever surprised, forever excit- ed”) “finds a word of Bantu origin and leaps to the conclusion that everything before his eyes is Afric- HEMISPHERE Too old to play properly or give reliable information, guitarist in Argentine village of Valle Fértil wanted to help and would have been hurt if not asked to perform. an.” Miss Aretz nelieves that the good folklorist acquires an insight into the fundamental nature of a coun- try that nothing else can supply. Formed by spontaneous choice from among a number of available influences, and in turn influencing future development by filtering back into more sophisticated levels of society, a nation’s folklore is the truest possible guide to its tem- perament. City intellectuals’ elab- orate notions about the character of their country are frequently not to be trusted, for they fail to take into account what the bulk of the population actually thinks and does. Miss Aretz says: “Many Ar- gentines I know make comments, admiring or disparaging, about the exotic folklore of other Latin Ame- rican countries. It never occurs te them that we have any such thing in our country That’s because they never go a hundred miles out of Buenos Aires and look around.” Whatever happens today to a specific work song in Venezuela or a saint’s day procession in Pert, folklore will not die. It is constant- ly being re-created. Some of our modern songs, dances, jokes, and fads will perish. Others will fill such a need that they become part of the common store of culture, and a hundred years from now the successors of the Ramon y Riveras will be patiently tracing, extract- ing, and studying them. Chiambanguele, as danced in Mérida State, Venezuela, in honor of St. Benedict, the Negro saint, has lost African characteristies, Instruments used te accompany Venezuelan carols. Im rear, mats dolin, furruco (played by rubbing moinstened hand up and dowa long reed),- cuatro; im foreground, tambourine made with beew botle caps, maracas. ~=* ed