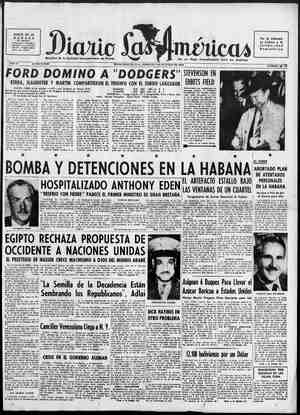

Diario las Américas Newspaper, October 7, 1956, Page 22

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

a “ THROUGH THE SOUTH AMERICAN HINTERLAND WITH TWO MUSICOLOGISTS By BETTY Francisco Peralta, best musician WILSON of Tucuman. Old traditions are still strong in this part of Argentina, on which Isabel Aretz is ranking authority. ONLY A CURMUDGEON would cavil at progress — would object when a highway opens up a remote region or a new industry turns a backward village into a modern boom town. The folklorist gamely rejoices along with the rest of the population, but there is no point in denying that his better nature is put to a severe strain. His business is to collect and study the songs, dances, poetry, stories, sayings, and customs of veople as unaffected as possible by self-conciousness and contemporary urban sophistication. It is getting harder all the time. Two of the most distinguished Western Hemisphere contestants in the race against the bulldozer, the popular press, and the TV set are the husband-and-wife musicologists Luis Felipe Ramon y Rivera and Isabel Aretz. Dr. Ramon y Rivera has been director of the Venezuel- an National Institute of Folklore and chief of its musicology sec- tion for the past three years; his wife, a lively, reddish-haired Ar- gentine who, he says, “was already famous when I met her,” has roved the byways of South America do- ing research since 1939 and is now technical adviser to the Institute. They are engaged in assembling the Latin American material for a folk- music collection, tentatively titled Music of the Americas, to be pub- lished under the joint auspices of the Organization of American States, the International Music Council of UNESCO, the Interna- 4 tional ‘nstitute of Folklore. Under 3 the general editorship of Charles Seeger, retired chief of the Pan American Union music section, this exhaustive work will appear in two editions: one, a special technical version in English, to be printed in London; the other, in English and Spanish and designed for the gen- eral public, by the OAS. Recently } they accepted another responsibili- ty — to select and record Latin American folk music for West- minister, one of the major U. S. re- cording firms. “It used to be,” said Miss Aretz, “that folklorists spent a good deal of their time arguing about theory and defining their terms. Nowa days we can’t afford to. We have to pick up every scrap of material we ean before our civilization destroys it, and till that’s done speculation will simply have to go by the board.” “Not long ago,” amplified her husband, “while we were on a re- search trip in an isolated part of central Venezuela, we stopped at a tobacco plantation to interview some Indian workers — Guaraunos. They had come down from the mountains only a week or so earlier and spoke no Spanish, so we had to deal with them through an inter- preter. At last we relayed to them a request to perform their songs and dances for us, but we didn’t need the interpreter to understand their answer, They said: ‘O.K.’ That is the sort of thing we musicolog- ists are up against.” Just what it is that constitutes a musicologist has been delineated by Ramon y Rivera in a monograph on the polyphonic music of the Ve- nezvelan Manos. Any number of trained professional musicians na- tive to the plains region had been in contact with this music all their lives and never noticed anything of particular interest in it. But music- ologists were greatly excited when the first description of it was pub- blished by José Antonio Calcano. How had this complex, highly cul- tivated part-singing, of a kind so difficult that it has almost disap- peared from folk music, come to Reprinted from_ AMERICAS, monthly magazine published by the Pan American Union in English, Spanish and Portu- guese. the Venezuelan backlands? How did it sound? Most important of all, considering how improbable it was that unschooled singers could pass on such an art from generation to generation, was it not likely that Caleafio was mistaken? Since this primary doubt could only br resolved by concret evid- ence, in 1947 the Ramon y Riveras packed a tape recorder into a jeep and rove off to the Manos. First they confirmed their colleague’s discovery. Then they set out to learn more about it: they listened to versions similar in type to me- dieval polyphony, they heard forms that in varying degrees resembled the other regional folk mu- sic, they examined all they found out in the light of their training in music and folklore, their pre- vious experience and their general education. Next they tried to draw some conclusions about it: ap- parently polyphony had _ been brought to the Hanos somewhere in what is now Carabobo State, perhaps in its capital; its initiators were European-traned musicians, very possibly priests; it must date back to at least the eighteenth century, for the chaos of the early years of the nineteenth century allowed no one much concern over matters like the introduction of pre-classical music and public taste in the later years favored less austere styles such as Italian ope- ra; the variations they had. noted were quite typical, produced in the usual way by casual admixture of familiar elements (for example, accompaniment by the four-string- ed cuatro, whereas the pristine form is sung a cappella). Final- ly they recognized that relation- ships worth investigating might exist between these tonos Haneros and similar music found in Brazil by Oneyda Alvarenga, in Portugal by Gonzalo Sampaio, and in Tucu- man Province, Argentina, by Miss Aretz herself — in the musicolog- ist’s hairbreadth fashion, she had caught it just in time — but that not enough material was available yet to warrant generalizations. (left) im Venezuelan lianos. On such a trip, the musicologist (or other folklorist) must first gain the confidence of the com- munity. Given a choice of two or more place where he has reason to believe a piece of music or folk- lorie exists in tolerably authentic form, he will have selected the most remote. Establishing friendly rela- tions there may at times take up to a month — although, say the Ramon y Riveras, who of course are most interested in music but will gladly accept information on any other aspect of folklore that comes their way, it is much easier to induce people to part with their songs than with their beliefs or superstitions. The support of the local political or administrative chief carries a good deal of weight, sometimes he despises folk- lore as evidence of backwardness, but usually he is eager to help and perhaps to perform. The village elders are also pleased by the visit- or’s flattering attention: it gives Harpist and maraca-player record for Luis Felipe Ramon y Rivera them sudden prestige in the eyes of the young, who are prone to con- tempt of the old ways and who would like to play or sing for the musicologist themselves but are re- jected because their performance is not authentic. After the tape-recording session come the questions — Where did you learn this song? Where did he learn it? How was it sung when you were a boy? — repeated with endless patience and to as many people as necessary to assure the musicologist, first, that he has got the answers straight and, second, that they are accurate (for ex- ample, a man’s dogged statement, even his profound conviction, that he made up a song himself is no proof that he did so). When the musicologist has learned all he can in the village and has it all down in detailed, exact notes, he moves on to a neighboring town to make eomparisons. These research trips are any» Dance perfomed on Day of SS. Peter and Paul (June 29) in villages directed against rich whites. In colonial days, region was made wp of Guarenas and Guatire, Miranda State, Venezuela, is satire of cacao plantations owned by aristocrats and worked by slaveg Pagina 10 HEMISPHERE ‘ SUNDAY, OCTOBER I, 1986