Evening Star Newspaper, October 10, 1935, Page 14

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

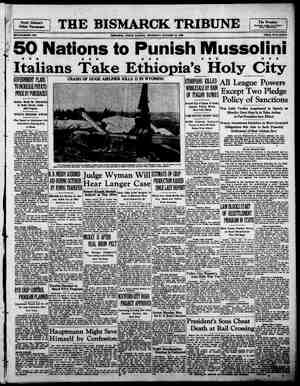

< A—14 THE EVENING STAR, WASHINGTON, D. C., THURSDAY, OCTOBER 10, 1935. JUDGE TRENCHARD UPHELD IN COMMENTS ON EVIDENCE PART OF HIS DUTY T DISCUSS DATA tharge to Jury Held Favor- able to Defense if at All Biased. (Continue¢ From Thirteenth Page.) N. J. Law. 36, where we held that in that case the absence of an exception would not bar a reversal and placed this on grounds of public policy. However, & glance at that case will ¢how a fundamentally different situ- ation in that the trial court in the conduct of a murder case disregarded one of the most fundamental rules of .the court procedure in such cases, viz., .that the jury should be sequestered “ sluring the trial. and in fact permit- | ted the members of the jury to dis- perse to their homes. This was in- deed a case of public policy, but does not, require the extension of the rule to what may be described as ordinary trial error. We deem Point III therefore to be without substance Point IV is a challenge in another form to the summing up by the at- torney general and read as follows: “The defendant’s constitutional rights under the fourteenth amend- ment of the Constitution of the Unitea States were contravaned by the sum- mation and material variance of theory.” This is said to be in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. Without repeating here what has already been said under the first point, we conclude that there was no such infringement of the Federal Constitution. Venue Issue F To Bring Reversal. Point V is headed “the venue was improperly laid in Hunterdcu County instead of Mercer County.” What is meant is that the indict- ment, if any, should have been found in Mercer County and tried there. It | will be remembered that the child | when stolen was in Hunterdon, and | that the body was found in Mercer. | Counsel, of course, recognized the pro- | visions of section 59 of our “Criminal | Procedure Act” (C. S.1839) that where there is a felonious striking in one county, and death therefrom occurs n another county, the indictment may be found in either. Parallel with this is sectior 60, cov- ering cases where felonious striking is without the State and death 1 the State. The case of State vs. James, 96 N. J. Law, 132, was a case covered by section 59. Under section 60 we have the recent cases of State Vs. Lang. 108 N. J. Law, 98, and State vs. Prazer, in the same volume at page 504, The gist of the argument. both orally and in the brief, was and is that there was no evidence to justify the jury in a finding that there was any felonious striking in Hunterdon County. The court charged that “the fact that the child's body was found in Mercer County raises a presumption that the death occurred there. But that, of course, is a rebuttable pre- sumption and may be overcome by circumstantial evidence.” Clearly the jury were entitled, in view of the evidence, to find that gome sort of battery was committed in Hunterdon when the child was taken from its bed. and from that evidence might also find that the blows on the head, causing death, were inflicted in Hunterdon. It was not necessary to show death in Hunterdon. Proof of a felonious strik- ing in that county. causing death that ocurred, was sufficient. And we consider that of such striking there was sufficient proof, even though of @ circumstantial character. ,Opinion Finds Evidence ©Of Common Law Burglary Point VI is stated thus: “There was no proof of the common law crime of burglary, and the court erroneously charged the statutory crime.” This, it will be observed, contains two propositions. Both are incorrect. There was proof of common law burg- Jary, and the court did not charge what the thief calls “the statutory ecrime,” 1. e, section 131 of our crimes act, C. S. 1787. As to the first—a burglar, says Blackstone (4 Blk. 229) following Coke, is “he that by night breaketh gnd entereth into a mansion house with intent to commit a felony.” In 1 Russ. Crimes 785, burglary is de- fined as “a breaking and entering the mansion house of another in the night with intent to commit some felony within the same, whether such feloni- ous intent be executed or not.” In State vs. Wilson, 1 N. J. Law- Coxe 439, Chief Justice Kinsey, charg- ing a jury defined burglary as “the breaking and entering in the mansion house of another with the intent to commit some felony therein, and that in the night time.” There was proof to meet all these conditions—a breaking and entering, and into a mansion house, in the night time—and with intent to commit a felony. Only the last merits any particular discussion. The intent is to be gath- ered from what was done. viz.: The stealing of the child and its clothing, #s charged by the trial judge. Kid- naping was no felony at common law, but larceny was a felony, whether grand or petit (4 Blk, 941,299 et seq.). It is suggested that there was no proof of value of the clothing and hence that proof of larceny was in- compelte, but we see no merit in this. The matter of value was material in trying an indictment for larceny—and perhaps also in framing such indict- ment—because of the greater punish- ‘ment in cases of grand larceny, but, as Blackstone says ubi supra, grand and petit larceny are “offenses which wre considerably distinguished in their punishment, but not otherwise,” and in treating of burglary the distinction 4s not even alluded to. As to the first proposition of point VI, therefore, we think it clear that there was suitable proof of the com- mon law crime of burglary. Then as to the second proposition we are equally | clear that the court did not “erro- neously charge the statutory crime.” By this phrase counsel mean the of- fense or offenses denounced by section 331 of the crimes act, which reads as follows (C. S. 1787): “Any person who shall, by night, willfully or maliciously break and en- ter any church, meeting house, dwell- ing house, shop, warehouse, mill, barn, gtable, outhouse, railway car, canal hoat, shio or vessel, or other building hatever, with intent to kill, rob, steal, commit rape, mayhem or/battery, and His counselors, procurers, aiders and 1 No. | MANN, wife of the convicted murderer, who fought by his side in an effort to provide him with | an alibi for the night of the crime. | No. 2—ALBERT S. OSBORN, handwriting expert, who testified | Hauptmann was the writer of the ransom notes. No. 3—ARTHUR J. KOEHLER, Government wood expert, Wwho | traced lumber used in the kidnap ladder to a Bronx lumber yard and \ testified the wood used in the ladder uprights was the same as that found in the attic of Hauptmann's Bronx home. No. 4—BRUNO RICHARD HAUPTMANN, the date of whose execution will be set by the trial Jjudge. No. 5—ATTORNEY GENERAL DAVID T. WILLENTZ of New ! Jersey, dapper, fiery prosecutor. | No. 6—EDWARD J. REILLY, | Brooklyn attorney. who conducted the defense during the trial, but withdrew before the appeal was filed. No. 7—BETTY GO' bergh baby's nurse. No. 8—DR. JOHN F. (JAFSIE) | CONDO! Bronx educator, who | identified Hauptmann as the “John" to whom he paid $50.000 ransom over a cemetery fence, No. 9—The Lindbergh baby. No. 10—COL. CHARLES A. LINDBERGH, the father, No. 11—MRS. ANNE MORROW | LINDBERGH, the mother. | —A. P. and Wide Woerld Photos. W, the Lind- | abettors, shall be guilty of a high misdemeanor.” Find Court Charge Favored Defense. When this language is examined. it will be found that while the word ! “burglary” is not used, the common law offense on burglary is fully in- cluded, and thereby made a high | misdemeanor. together with offense not amounting to a common-law bur- glary, either because committed in other buildings or with intent to com- mit some other offense not amounting to a felony, particularly a battery. But the elements of common-law burglary are all mentioned, viz.. the breaking and entering by night a dwelling house with intent to steal. The trial judge, mentioning the statute, it is true. and quoting section 131 in part. proceeded to instruct the | jury as follows: “If, therefore, the de- fendant by night willfullv and ma- liciously broke and entered the Lind- bergh dwelling house with intent to steal the child and its clothing and | to commit a battery on the child, he committed a burglary. and if the mur- | der was committed in perpetrating a burglary, it is murder in the flrst | degree.” Conceding for present purposes the claim of counsel for plaintiff in error that by “burglary” as mentioned in sections 106 and 107 the Legislature intended burglary at common law. the quoted instruction was, if anything, too favorable to the detendant, for it postulated an intent not merely to steal the child’s clothing, which would | have sufficed, but as well an intent | | to steal the child and to commit a battery. These, we would point out, | were not joined in the alternative but in the conjunctive. To consti- | ute burglary, in the language of the | instruction, all three must be in- | cluded in the intent. Hence the error, | if any, was prejudicial to the State rather than to the defendant. We have just said that for present | purposes the construction put by de- fendant’s counsel on the word “burg- | lary” in sections 106 and 107 may | be conceded, but the question was alluded to in State vs. Jones, 115 New Jeresey Law, 257, at pages 263-4, | and there passed, and it is needless to consider it now, for reasons just | given. Child's Garment Basis of Theft. Point 7 is that “there was mo evidence of intent to steal, and the court erroneously charged the jury” on that point. | The evidence tended to show that | the child when stolen wore the sleep- | ing garment, that there was no such | garment on the body when it was ! | found. That defendant had this gar- [mcnl in his possession. That he so | told Dr. Condon at the outset of nego- | | tiations for ransom and agreed to | send it to him as evidence that Con- |don was dealing with “the ‘right party.” That he wrote Condon say- |ing that the ransom would be $70,- | 000 and that “we” would send the sleeping suit though it would cost | $3 to obtain another one. That ‘the | ransom must be paid before seeing the baby and eight hours after pay- ment Condon would be notified where to find the baby. The sleeping suit came by mail and then Condon put a reply advertise- ment in a New York paper accepting the proposition conditionally. The claim now made is that in | view of the surrender of the sleeping suit there was no larceny. Relying on the rule declared in such cases as State vs. South, 28 N. J,, Law, 28, that | an intent to deprive the owner perma- | nently of his property must be an ele- | —MRS. ANNA HAUPT- < lout leave and with intent to relurnlder. and if while there engaged in securing his plunder, or in any of | | ment in the taking ofsthat property, 50 in a class of cases'#hich may be ! loosely described as borrowing with- ' Summary of Hauptmann Kidnap-Murder Case in Pictures > after temporary use. A similar case is State vs. Bullitt, 64 N. J. Law: 379 in State vs. Davis, 38 | Id. 176, it was held that abandon- ment of the “borrowed” property (a horse and wagon) justified an infer- ence of an intent to deprive the own- er permanently of his property. But the intent to return should be uncon- ditional, and where there is an ele- ment of coercion, or of reward, as a condition of return, larceny is infer- able (36 C. J, 769, Sec. 122). Mr. | Bishop adds “and perhaps it should be | added, for the sake of some advan- tage to the trespasser—a question on | which the decisions are not harmoni- |ous” (2 Bish. New Crim. Law. Sec. | 758, especially note 22, Id. Sec. 841 A, Sec. 842.) At Sec. 843 he says: “But the true view where the rule of luci causa is concerned, is simply that he should mean some advantage to himself. in | distinction from mischief to another Sleeping Suit Used As Extortion Aid. In Com. vs. Mason. 105 Mass.. 163 it was held larceny to take a horse found astray on the taker's land. and conceal it either to get a reward when | advertised, or induce the owner to| sell it “astray.” In the present case the evidence pointed to use of the sleeping suit to further the purposes of defendant and assist him in extorting many thous- ands of dollars from the rightful owner. True, it was surrendered with- out payment. But on the other hand it was an initial and probably essen- tial step in the intended extortion of money. and it seems preposterous to suppose that it would ever have been surrendered except as a result of the | first conversation between Condon | and the holder of the suit. and as a guarantee that there was no mistake as to the “right party.” It was well within the province of the jury to infer that if Condon had | refused to go on with the preliminaries the sleeping suit would never have | been delivered. In that situation, the larceny was established. Point 8 is that “the burglary, if any, was complete in Hunterdon County and separable from the mur- | der, presumed to have been committed in Mercer County.” The gist of this is that the burglary, if any. was compiete before any homi- cide was committed. That would be largely a question of fact in any event. But in dealing with it, the rule ap- plicable is not that of the New York cased cited in the brief, but of our New Jersey courts, laid down in such cases as State vs. Carolino, 98, N. J Law 48, State vs, Turco, 99 id. 96, cited by plaintiff in error, and State vs. Gimbel, 107, id. 235. To these may be | added State vs. Mule 114, id. 384, in | which the New York case of People | vs. Giro, 197, N. Y. 152, 90 N. E. 432, | is cited with approval. As to the argument that the crime of burglary is complete when there is a nocturnal breaking and entering with intent, that is doubtless true for | the purposes of a conviction of bur- glary. Bul we think it not applicable to a homicide in the commission of | a burglary. It would be strange, in- deed, if this court were to hold, in & case where a burglar has made his entry, is packing up his loot, is chal- lenged by the master of the house and | shoots and kills him, that the Stfltu-i tory first-degree rule does not apply | because the “burglary” is incomplete. Evidence Showed Death in Burglary. As to this the New York Court of Appeals said in Dolan vs. People, 64 N. Y. 485 at page 497: “If a burglar break into a dwelling house burglariously with the intent to steal, the offense is doubtless com- plete before he leaves the building, but he may be said to be engaged in the commission of the crime until he leaves the building with his plun- WE CARRY GOLD SEAL CONGOLEUM RUGS AND FLOOR COVERING Phone for Estimates THOMPSON " BROTHERS FURNITURE 1220 Good Hope Rd. S.E. the acts immediately connected with the crime, he kills any one resisting him, the statute.” The rule stated in the text of 29 C. J, 1107, and which for present purposes we approve, goes some what further, saying: “A murder may be committed in the perpetration of a felony, although it does not take place until after the felony itself has been technically completed, if the homicide weeech as 20 on JEAN BLAKE: “THIS HALL FLOOR CER- TAINLY LOOKS SHABBY, JIM. DO YOU SUPPOSE WE CAN AFFORD A NEW INLAID LINOLEUM FOR IT?". .. JIM BLAKE: “I| WONDER—WHY NOT PRICE IT AND SEE?" he is guilty of murder under | 1 is committed within the res gestae | titled to find that the child was killed of the felony.” | | while the “burglar” was still on the This seems to be the rule applied, | Lindbergh premises and, if so, the if not stated in this language in our cases above cited, and, indeed, conceded by counsel for defendant in moving for a directed acquittal when the State evidence was in. The con- cession was limited to a situation involving grand larceny at common law, but we have already dealt with that matter. Applying it to the case at bar, we think that the jury were clearly en- homicide would be murder in the first degree under sections 106 and 107, supra. | Poin® 9 is a further discussion of the case of State vs. Jones, 115 N. J., law, 257, already mentioned, We have already said, and repeat, that the alternative theory of homicide sug- gested in the summing up by the attorney general was not adopted by the court, nor submitted to the jus Consequently this point is without substance. Point 10 is argued at considerable length, the discussion taking up some 20 pages of the printed brief. The | heading of this point reads as follows: | “The court by its charge .mpaired | a verdict and impressed upon the jury | his conclusion as to the evidence and | imposed upon the defendant an un- | | authgrized rule | doubt.” as to reasonable | Again the point consists of two legally distinct propositions. The first is the alleged erroneous comment on | the testimony and the second the al- leged misstatement of the reasonable doubt rule. ‘Taking up the first: The discus- sion relates more particularly to the judicial comment on the Condon testi- | mony, the circumstantial evidence. The note said to have been found on the window sill, the matesial of which the ladder was constructed, the ran- som money and the story about Fisch, the testimony relating tc the thumb guard, the evidence of alibi and the testimony of the old witness named Hochmuth. Counsel sum up the criticism on the first branch of point 10 by saying: “These remarks and charge of the court on the question of circumstan- tial evidence controvert and upset every legal postulate hitherto em- bedded in our system of criminal Jurisprudence.” Judge'’s Duty Calls For Evidence Comment. ‘The brief under this point ignores | one of the most thoroughly settled rules in our New Jersey criminal juris- prudence. That rule is that “it is al- | ways the right and often the duty of a trial judge to comment on the evi- dence, and give the jury his impres- sions of its weight and value, and such comment is not assignable for erorr s0 long as the ultimate deci- sion on disputed facts is plainly left to the jury.” (State vs. Overton, 85 N. J. Law, 287.) ‘The writer of the briel appears to take the stand that was taken by counsel for the plaintiff in error in the Overton case, viz.: that “a trial judge should not intimate any opinion upon the facts.” still later case of State v. o il SALESMAN: "“THE ADHESIVE IS ON THE BACK OF THE LINOLEUM ITSELF, MRS. BLAKE...IT TAKES A LOT LESS TIMETO LAY IT AND SO CUTS THE COST ABOUT 20% ON THE AVERAGE JOB."” The adhesive on the back also saves time— floors laid in 2 to 3 hours,* ready for use... Just imagine a real Sealex Inlaid Linoleum floor laid in a few hours without any fuss or muss... and at a big reduction in cost! You can have it today — thanks to this wonderful new floor- covering with the adhesive right on the back— Adhesive Sealex Linoleum. You get a stronger, longer-wearing installation, 100, for the adhesive holds every inch tightly to the floor! And you save real money as well. Stop i MADE ONLY BY CONGOLEUM-NAIRN INC., THE WORLD’S LARGEST MANUFACTURER OF FLOOR.COV Line. 0556 at your dealer’s and see the lovely pat- terns now available in this sensational, new floor-covering! HAVE THIS LINOLEUM GOES DOWN FAST."” AND AT A BIG SAVING IN PRICE, TOO!" *Estimate based on average floor of about 15 square yards. A Adhesive Sealex Linoleum is an exclusive Congoleun-Nairn product, protected by U. S. Patent No. 1,970,503. ADHES/VE SEALEX LINOLEV TRADEMARK REGISTI i ki A i fl:kflv.um.nm.w.m i Corrado, 113 N. J. Law, 53, at page 59, the opinion speaks of ‘“certain comments of the trial judge on the evidence, interrogative and argu- mentative in character, as calcu- lated to influence the jury unfavor- ably to the defendant. These com- ments were in n0 WAy erroneous. The right of the trial judge to give ihe jury the benefit of his individu- al view of the evidence, so long as he is careful to avoid controlling |them by a binding instruction, is steeled in the State beyond perad- venture.” The rule has obtained in full force for many years. In Donnelly v. State, 26 N. J. Law, 463, affirmed at page 601, two assign- ments of error alleging that the court, by its charge invaded the province of the jury by arguing the facts of the case, and also that the court in said charge did give a partial view of the evidence against the prisoner. and omitted the circumstances in his favor, were held not to constitute a legal ground of error, or of a bill of exceptions. In Bruch v. Carter, 82 Id. 554. a civil case, this court held that “a judge has an undcubted right to make such comments upon the testimony as he thinks necessary or proper for the di- rection of the jury.” There are further remarks on the point unnecessary to reproduce here, but all of the same purport. Court Rulings Back | Comment by Judge. In Castner vs. Sliker (38 Id. 507), also in this court, the then Chancellor Zabriskie, in commenting on certain rather strong language in the charge which is quote at page 511, pointed out that the ultimate finding of facts was left with the jury and concluded “It is the right and duty of a judge to comment upon the evidence, and in cases where he thinks it required for the promotion of justice, to give his views upon the weight of it. provided he leaves it to them to decide, upon their own views of it. This is too well settled by repeated decisions to be now called in question.” In the case of Smith and Bennett vs. State (41 Id. 370), the comments of the trial judge were held erro- neous on the specific ground (page (Continued on Fifteenth Page.) every *| D usually sperdt for INLAID LINOLEUM FLOORS WORKMAN: “DON'T WORRY, LADY, I'LL LAID IN PLENTY OF TIME TO SURPRISE YOUR HUSBAND. THIS NEW ADHESIVE SEALEX LINOLEUM JIM BLAKE: “ADHESIVE RIGHT ON THE BACK OF THE LINOLEUM, JEAN? AND DOWN IN 2 HOURS? SAY, THAT'S A SWELL INVENTION! A LOT OF PEOPLE WILL JUMP AT THE CHANCE OF GETTING A REAL INLAID LINOLEUM FLOOR SO EASILY ..