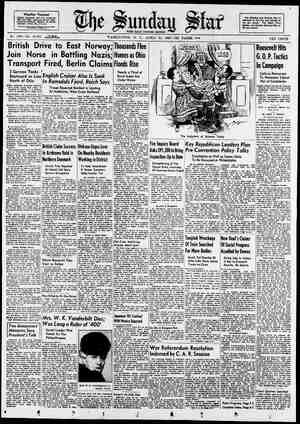

Evening Star Newspaper, April 21, 1940, Page 87

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

A Short Story Complete on This Page * * * Y FRIEND Barry Graham prided him- M self on the fact that he would never do anything that interfered with his liberty, or put him under the necessity of doing anything that he did not wish to do. The result was that we all regarded him as the most absolute example of the selfish person we had ever met. Life began by pampering him. He was born into one of the first dozen families which inherit the earth. Wherever he traveled — and that was everywhere — he had the irri- tating habit of always finding that an uncle, a cousin, a nephew or a second cousin was the Ambassador, Minister, or, at the lowest, British Consul in the capital, where he al- ways took a suite comprising bed- room, bathroom and sitting room on the quiet side of the hotel. Barry was never mean, but he was cautious. He would give money away to strangers but he would not lend it to friends. Friends, he knew, would always feel that he would not press them for repayment; and what they conveniently forgot he incon- veniently remembered. It made his relationship with them uncomfort- able. The stranger could always be dealt with by a solicitor’s letter. Barry had a passion for employing his solicitor, who would be invoked to deal with a quarterly telephone bill in which two local calls had been wrongly charged, or with the insur- ance company that disputed a claim based on a hole burnt in his hat at a movie by a neighbor’s cigarette. Barry married the right sort of girl, a peer’s daughter, related to everyone who mattered. They lived together for fifteen years, and no one knew that they barely tolerated each other, so perfect was their politeness in public. When it became clear that there would be no chil- dren, Lady Diana looked elsewhere for romance, and one day asked Barry to divorce her. After the divorce, Barry went to visit a Chief Justice cousin in Burma. He came home after four months, via Athens. It was in that Greek city that something hap- pened which resulted in his becom- ing a figure of romance ten years later. This visit to Athens came at a time when a little house painter, out of work in Munich, was peddling crude oil paintings of the Bavarian highlands. The gods who rule from the invisible world, and make a tangle of our lives with their ravelings of the skein of Fate, tied one of its strands round the legs of a boy of ten in Athens, made a loop round the heart of self-satisfied Barry Graham in the best suite of the Hotel d’Angleterre, and tied the other end round Adolf Hitler, born Schukelgriiber, conspiring from a beer house to overthrow the new German Republic. But let us return to Athens. The British Consul there, to whom for once Barry was in no way related, told him the sad story of a young English pianist who had died suddenly, leaving nothing in that torrid city except a portfolio of music, a battered portmanteau, and asmallsonof ten. Somewhere in Billericay, England, (““Where?"’ queried Barry, peevishly) the small boy had an old aunt to whom he must go. Would Barry, returning in a few days, keep his eye on a small boy traveling via Brindisi, steerage, with a label on his arm? “Oh, very well,” responded Barry, finding it too troublesome to say, ‘“No.” Twelve hours’ sailing from the Piraeus, Barry remembered the small boy but could not remember his name. He braved an odor- ous passage to the other end of the ship, and, in a heap of drab humanity impregnated with garlic, found the small English boy, whose eyes were swollen with tears and whose fingers were sticky with pomegranate juice. Like a small dog sick with distemper, Barry made him follow at his heels. In his cabin the Greek steward stripped the small boy, and Barry, regarding the juice-stained Cupid about to be sluiced with sea water, inquired his name. *“‘Achilles,” said the sad-eyed little boy. “What?” ejaculated Barry. “Achilles,” repeated the small boy. " “And what else?”’” demanded Barry deri- sively. THIS WEEK MAGAZINE “What fools parents are!" exclaimed Barry 7 ES / N\ The dramatic story of how a chance meeting remade the life of a playboy by Cecil Roberts Hlustrated by James Schucker “Heel,!” said the small boy, eyes downcast. “Achilles Heel — Oh, my soul, what fools parents are!” exclaimed Barry, and went up on deck to smoke a Sobranje cigarette, while the wine-dark sea of Odysseus parted at the bows where the dolphins leapt. THE news got round the London clubs very rapidly. Barry Graham had adopted a small boy found on the deck of a Greek steamer. The small boy was a Greek — no, a half-Greek —no, not quite that. His mother was a Cypriote — half-Greek, half-Turk — but of British nationality, since Nicosia was her birthplace. An English pianist, consumptive and penniless, appearing with a concert party in Constantinople, had met her on a boat proceeding to Rhodes, where she danced in the cabaret at the Grand Hotel. All nonsense, said Harry Colefax; the boy was one hundred per cent British. He had seen the boy, a little thoroughbred if ever there was one. The exact truth was never known. Within six months no one cared. No one even remem- bered that Barry had adopted a small boy. The child never appeared. Barry never spoke of him. But ten years later, at the Junior Carlton Club, Barry gave his friends a dinner party — and a shock. A youth with the head of Antinous stood beside Barry in the smoke room as he welcomed his guests. “You know Arthur?”’ asked Barry, blandly, knowing well that only two out of the eight of us had ever seen the boy before. At dinner he sat between Hugh Dalrymple, a quizzer of the first order, and Jack Somers, the cavalry officer. The boy emerged with full points from 7 a raking cross-examination. He’d had his schooling at Marlborough, going from there to Exeter College, bound later, perhaps, for the Civil Service. “Gard says I'm to study law, but I’'m not bright enough, I fear,” said Antinous, with a dazzling, modest smile. “Gard?” queried Dalrymple. “Who's Gard?” “Guardian,” answered the boy, looking across at Barry, raising his port glass, an inch of immaculate cuff emerging from his sleeve. Gard, synonym for God, 1 thought, seeing the worship in the boy’s eyes. ““Oh, yes, of course!’’ said Dalrymple, smothering his surprise. This, the Greek foundling, found in a heap of rubbish on a Greek steamer, picked up at a whim, edu- cated at a public school, and now produced by Barry without a single word of explanation! THE pleasant dinner came to an end. We shook hands with the boy, smiled at Barry, and none of us said a word. I was as intimate with Barry as anyone in his circle. He might have had the grace to tell me about the boy. I could have shared in his triumph and have congratu- lated him on all he had done. But not a word did he say. The August holidays separated us. We went to various corners of an uneasy Europe, I carrying my rheu- matism to Aix-les-Bains. Hitler’s march into Poland brought me scur- rying home, and then Chamberlain’s - fateful words on that Sunday morn- ing in September ended the pleasant England of accessible gasoline pumps and evening lamplight streaming across the dark green lawns. A month passed, with all of us scurrying round, anxious to make ourselves useful. At long last my own course was set, and a day came when my baggage lay labeled in the hall and I looked upon the October gold of an England I might not see for a long, long time. Those last desperate letters, those last drawers locked, the last visit to lawyers and house agents and travel agents — all had been achieved. I looked at the neat list on my desk; a coal bill paid, tooth paste, new shoes, sun glasses, shirts, typewriter ribbons; a tick against each item set my mind at rest. Then, with a groan, I saw my servant come in with some let- ters. They could not possibly be answered. I would read them, at my leisure, on the boat train. WXTHIN half an hour of leaving the shores of England, with gulls whirling around the liner’s stack, I remembered the letters in my valise. Two were of no importance, but the third made me start. The heading seemed a joke. It read: Private Barry Graham No. 7,756,835 C. Was it possible any human being could have such a number? And Barry Graham, once a dapper cavalry captain in the Great War No. 1, now a private! Why, he was fifty, if aday! And a private — Whatever . . . ? . ..well, here I am. We don't get nearly enough sleep, but it’s all great fun, and I'm with Arthur. It took a terrible lot of wrangling but I was very determined and they were very kind. But I suddenly realized how I should miss the boy. They won’t send him out for some time yet, and I hope they’ll let me go too — no reason why they shouldn’t, for I'm only a number here and you just let the stream carry you along. I didn’t think I could be so young or develop such a great appetite. ““I feel a bit guilty at keeping the car at a nearby garage, but it does enable us to run into T——, for a meal at the hotel, by way of a change. Food here not bad, though cooked by a chartered accountant . . . the Lord knows where we’ll all end up . . . but I'm happy as I've not been happy for a long time. Send me a line if you can find time...” I found time, just before the gangway went up, greeting that gallant connoisseur of the best food, the best hotels, happy with his Achilles Heel. The End