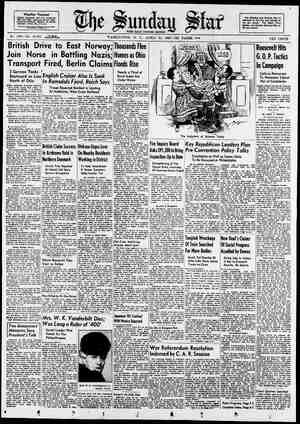

Evening Star Newspaper, April 21, 1940, Page 31

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

— Oil Assumes Great Importance In Politics Here and Abroad Federal Regulation, Latin American Situation, World Aflame With War Thrust Petroleum Into Limelight By Marquis W. Childs It has been said that the story of con- temporary politics can be told in terms of oil. If that is an exaggeration, it is certainly true that oil has figured vitally In almost every important political con- test in recent decades. This is as true of tie coming campaign as of past ones. Occasionally the political maneuvers centering around this vital commodity are apparent. More often they~ take place behind the political stage on which | less realistic issues are debated. But almost invariably the private interests contrélling oil are a factor. Their power is over a product almost as essential to modern life as food—in a mechanized world all depends in great measure on oil. In 1940 oil will be an important issue In an election which may well be a turning point in American life. In three ways it comes into the politics of this election year. First, there is the comparatively sim- ple question of Federal regulation of the Industry. Secretary of Interior Ickes has come out for Federal regulation in the interest of conservation. He would police the inéustry to prevent waste, in an ef- fort to'conserve America’s rapidly shrink- Ing reserves. This move has been op- posed by virtually the entire industry, the so-called independents along with the big companies. Latin American Question. Second, there is the more complicated fquestion of oil in Latin America, a ques- tion tied up with the right of Latin American countries to expropriate for- eigners’ property and the whole position of the United States “south of the bor- der.” The oil companies are very likely to promote the issue of Mexican expro- priation, perhaps condemning the pres- ent administration for not taking a *“stronger” stand. And this will be point= ed not so much at recovery of Mexican properties as at retention of the vast oil stake in Venezuela and elsewhere. Last, and by no means least, comes the whole matter of world oil politics as it relates to the war in Europe and the American attitude toward the war. The late Sir Henri Deterding, head of the Royal Dutch Shell Co., had thrown in his lot with the Nazis, seeing in them a last hope for recovery from the Soviet— for the “West,” for “civilization,” for Shell perhaps—of the great oil fields of Baku. Before his death a year ago he was disillusioned in that hope. In fact, according to his associates, this disillu- sionment contributed to his death. In any event, the oil of Baku, the oil of Persia and the Far East, is one of the great prizes for which the war is being waged. Even so conservative a thinker as Calvin Coolidge once remarked, “It is even probable that the supremacy of nations may be determined by the pos- | session of available petroleum and its products.” Both sides in the present conflict know that all too well. Before 1933 there was no effort in the United States to regulate the oil indus- try. Just a few years before the New Deal the great East Texas field came roaring in and the domestic market was | flooded with oil. The price went down to | 10 cents a barrel for Mid-Continent crude, less than the cost of production. Under the royalty leasing system wild- caiters were making quick kills, leaving priceless and irreplaceable deposits of oil in the earth in such a way that they could never be recovered. N. R. A. Checked Some Abuses. Confronted with this chaos, even the oil operators were prepared- to accept some kind of regulation. They came under the Blue Eagle of the N. R. A. and this far-reaching instrument served at least to keep up the price and prevent some of the worst abuses. What it did not do, according to Mr. Ickes and other conservationists, was to check the vast wastage that has gone on almost from the time when the first well in Pennsyl- vania was drilled. When the Supreme Court threw out the Blue Eagle, the major oil interests then sponsored the State compact idea for the contrcl of production. Senator ‘Tom Connally of Texas introduced and had passed the “Hot Oil” Act, permitting the Federal Government to halt the in- terstate flow of oil in excess of the pro- duction agreed upon by States entering the compact. Under the act, of course, the Governmenmt has no right to inter- fere with production within the State. ‘Whatever the compact system may have accomplished in the way of regula- tion, a serious flaw has been the fact that two producing States—California and Illinois—decline to enter the agree- ment. In California the question of State legislation to bring the industry within the compact was sharply fought over at the last election, with President Roose- velt, Secretary Ickes and other New Deal- ers plumping for a State law. While the oil companies indorse the compact idea, they oppose a, State law, on the assump- tion apparently that they can do the job without governmental interference. ‘Without these two big producing States the interstate compact and the “Hot Oil” Act are of little value. This is the argument of Mr. Ickes and the con- servationists who are backing the bill for Federal regulation introduced by Repre- sentative Cole, Democrat, of Maryland. Under the terms of this measure, on which hearings were held for many months, the Department of the Interior would act in an advisory capacity to regulate oil production. But the Government would also have authority to step in and compel abandonment of wasteful prac- tices when individuals failed to heed advice. Reserves a Defense Problem. The ‘chief argument of the conserva- tionists is the menacing depletion of American oil reserves, a threat which touches not only all of industry and finance, but, more vitally, sthe question of national defense. The Natural Re- sources Committee under Secretary Ickes in the Department of the Interior ap- pointed a special group to make a survey of the energy resources of the Nation. In a report issued last year these experts declared that there was only a 12-year known supply of petroleum in the United States at the present rate of production, It is just here, of course, that the ques- tion of foreign holdings comes in. Since 1918 the scramble for oil reserves in various parts of the world has been intensified. The major oil combines, backed by their respective governments, have been engaged in bitter warfare all over the globe for the stuff that makes the wheels turn. The British have long realized that the power of empire de- pends on oil. For that reason the gov- ernment created the Anglo-Persian com- pany and gave almost unlimited backing to Royal Dutch Shell. By far the largest American holding is in Venezuela, where Standard and Gulf have enormous oil reserves, their combined resources and production being | greater than Dutch Shell’s. The oil dis- | coveries have given Venezuela a vast | | temporary wealth. New Colombian Field. An important new field in Colombia is in process of development. This is the Barco concession in which major production is just starting. A Standard | subsidiary has a lesser holding in Peru. | Similarly in Argentina there is a Stand- | ard field which is comparatively small, supplying only about a fourth of Argen- tina’s own domestic needs. The gov- ernment of Bolivia canceled out Amer- ican oil contracts to the consterna- tion of oil executives, who saw in this the shadow of expropriation even though the amount of money involved was very | small. It is in Mexico that oil politics in re- cent years have been hottest. The ex- propriation of American and British properties on March 18, 1938, precipitated a bitter warfare that is not yet ended How much use the Republicans will make | of the Mexican oil issue can only be sur- | mised. They may make political capital of the long, drawn-out failure to reach a settlement, of other surface symptoms of trouble. It is a safe bet that they will not press any investigation which would show all that is back of the Mexican maneuvering. One Phase of the Whole. In the larger view, all this is merely counting romantic and biased accounts, it remains true that much of the history of the post-1918 decades can be written around the effort to recover the great oil resources of Baku that were national- ized after the Russian revolution of 1917. Such powerful men as Deterding never gave up the hope that the wealth of the Caucasus Mountains would some day be restored to private hands. Under ordinary circumstances the be- hind-the-scenes maneuvers of the oil powers are difficult to discern. With wartime censorship all knowledge is blacked out. What part oil diplomacy played in the outbreak of the present war will be known, if it is known at all, only long after peace has come. And that peace may determine where con- trol of oil reserves, and therefore where world power, shall lie. SALUTE FROM . AN EXPERT. ’ SUNDAY STAR, WASHINGTON, D. C, APRIL 21, 1940—PART TWO. Wheeler, Liberal Champion Fights to Win in Career Checkered by Defeats By Raymond P. Brandt. Characteristic camera shots of Senator Burton K. Wheeler—on the oratorical firing line and in contem- plative repose. THE original story for the motion pic- ture “Mr. Smith Goes to Washing- ton” was called “The Man From Mon- tana” and was based in part on the tem- pestuous career of Senator Wheeler. Will Hays vetoed the title and many drastic changes were made in the story before it reached the screen. But the original idea was sound, for Burt Wheeler's career is studded with epi- sodes more lurid than any in Frank Capra’s film. Furthermore, Wheeler at 58 looks like a screen Senator—or a President. He stands well over 6 feet. His head is large and well shaped. His small, ex- pressive hands—“gambler’s hands,” they have been called—constantly move from the wrist as he talks. He has “pres- | ence.” The salty New Englander who settled in Butte because card sharps got his money there and he couldn’t travel any farther has been fighting ever since. He has taken a licking again and again. He has been viciously framed at home and in Washington. He has been vili- fled outrageously. But waste no sym- pathy on him, for he can dish it out as well as take it. When he fights, he fights to win, rough and tumble, and he isn't dainty about his weapons. Just now he is riding high; he can unquestionably stay in the Senate; he is an avowed can- didate for the presidency. Anaconda Ancient Enemy. His first fight was with “the company.” When Wheeler says “the company,” he still means the Anaconda Copper Co. When he was a fledgling legislator in Helena, 30 years ago, Anaconda regarded | Montana as its private domain and the | coup de grace. Legislature was expected to pay homage. Wheeler joined the forces trying to send Thomas J. Walsh to the United States | Senate. Walsh was barely defeated then, but won his seat two years later, in 1912, and got President Wilson to ap- point Wheeler United States Attorney for Montana. That district-attorneyship, during the World War, continued Wheeler’s political | education. Super-patriots clamored for . | prosecution of “enemy” Irish and Ger- one phase of world oil politics. Dis- | man workers, syndicalists and labor leaders. Behind the agitation Wheeler sensed the hand of the mining interests maneuvering to crush unionism. Refus- ing to yield to the clamor, he was de- nounced and the spy hunters shrieked that Montana was a hot-bed of sedition because of his attitude. Wheeler’s answer was to go after war profiteers and grain speculators. But in 1918 he re- signed because he was told that other- wise Senator Walsh would be defeated for re-election. Thereafter Wheeler was offered ap- pointment as Federal judge in Panama, but refused because he was convinced that it was a trick of the interests to get him out of the State. In 1920 he ran for Governor. Mobs broke up his meetings, once chased him out ¢f town. He was the worst beaten Democratic candidate who had ever sought office in Montana. Two years later he won the senatorship by the largest majority ever given a sen- atorial candidate. Popular approval had caught up. with Wheeler’s views. Went After Daugherty. He had not been long in Washington when the Teapot Dome scandals broke. “I came to the conclusion that if Daugh- erty was the Attorney General he should be, he must have known about the whole affair,” Wheeler recalled the other day. “I prepared a resolution demanding his dismissal from the cabinet. Imagine my surprise when Joe Robinson of Arkansas got ahead of me by calling for the ouster of Denby, Secretary of the Navy. Joe persuaded me to change my resolution to a demand for investigation instead of dismissal. It passed, 66 to 1. During the debate Senator Willis of Ohio coined a political classic. Harry Daugherty, he sald, was ‘clean as a hound’s tooth.’ ” ‘Wheeler had only hearsay to go on. But just a few days before the hear- ings started he found in Ohio the bizarre Roxy Stinson, divorced wife of Daugh- erty’s most intimate friend, Jesse Smith, who had killed himself the year before in Daugherty’s apartment. Roxy broke the case wide open. Wheeler was severely criticized for using her as his principal witness, but this was rough and tumble fighting of the Montana kind. He was out to win. ¥ In revenge he was shamefully framed. Federal courts in Montana indicted him on the trumped-up eharge of “unlawfully accepting money to influence issuance of oil and gas prospectinig permits.” There was a blast from the opposition press: Wheeler was a demagogue, a subversive influence, the “most dangerous radical in America,” & friend of Moscow. In the midst of all this, Ray Baker, a | with Roosevelt. Democratic wheel horse, former director of the mint, told Wheeler he had heard the Republican administration would in- dict him in the District of Columbia as well if he joined Robert M. La Follette, wio had just been nominated for Presi- dent on a third party ticket. Wheeler already had refused to run, but now he got La Follette on the telephone and told him he had reconsidered. That is the story, here told for the first time, of | how Wheeler came to run for Vice Presi- dent in 1924. And, sure enough, the fol- lowing March he was indicted in Wash- | ington. He was acquitted in both courts | and exonerated in the Senate by an overwhelming vote. Beat Supreme Court Bill. In some respects his greatest fight was Wheeler, more than any other man, beat the proposal to pack the Supreme Court. He had been a New Deal supporter from the start, had | steered through the Senate some of its | most important legislation—for instance, | | the holding companies’ “death sentence” Most of his liberal friends—reluc- | act. tantly or otherwise—were for the Su- preme Court reorganization bill. In the opbosition were elements he had scorned and who had scorned him. But he did not hesitate; he was one | of the first to announce his opposition. | “A . liberal cause,” he said, “was never wori by stacking a deck of cards, by stuffing a ballot box or packing a court.” He had no hope of beating the bill when the fight began, but thought that he might be able to win modifications. | Popular sentiment gradually swung his way, Senators slowly were won over, and eventually Wheeler administered the Chief Justice Hughes had declined to testify before the Senate Judiciary Com- | mittee, although obviously the best per- son to present the views of the court. Wheeler went to see Justice Brandeis, his close friend. Telephone to the Chief | Justice, Brandeis urged; maybe he will write a letter. Wheeler demurred; he didn’t know the Chief Justice. “Well, the Chief Justice knows you, and what you're doing,” said Brandeis. He led Wheeler to the telephone, stood with his arm across the Senator’s shoul- ders as Wheeler made the call. Hughes was, possibly, just waiting to be asked. Next day Wheeler had an eight-page letter on which the Chief Justice and his law clerk had worked most of the night. The Supreme Court was not behind in its work, said the Chief Justice. The President’s proposal to add six more Justices would impair, not increase, the court’s efficiency. That letter killed the bill. No Longer Called a “Red.” Conservatives suddenly discovered this man Wheeler wasn't so bad after all. Has Wheeler himself changed? There is evidence that his views have broad- ened. The railroads shuddered when he became chairman of the powerful Inter- state Commerce Committee of the Sen- ate, in 1934, but they have found him notably fair and ready to hear both sides of any case. He made a speech last December to the National Associa- tion’ of Manufacturers which that organ- ization still is circulating in pamphlet form. It pleads for Government co-op- eration with business. Nobody calls him a “red” any more. But it is probable that though he is less impatient, not 80 sure of quick panaceas, he is un- changed fundamentally. He still is the spokesman for the agrarian West, for silver, for labor. To be for monetization of silver is good politics in Montana. A high price for silver means jobs for miners. And silver inflation would mean that farmers could pay off their debts with debased dollars. Wheeler has twice proposed coinage of silver at the Bryan ratio of 16 to 1. It is likewise good local politics to be against the Hull reciprocal trade treaties, for Montana is a cattle-raising State and fears competition of imported beef. This man from Montana, now 17 years in the Senate, is not a student in the sense that La Follette and Borah were; his liberalism grows out of personal ex- periences. He is essentially a scrapper, & courtroom lawyer. Born in Hudson, Mass, he talks the earthy Western ver- nacular with a residual trace of Yankee accent. He puts the New England “r” on “hadn’t orter” But he cusses in pure Montanese, He was the youngest of 10 children on a farm. After going through high school and a business college he worked in a hardware store, an optical goods factory and a lawyer’s office to scrape together $750, enough to enroll in the University of Michigan Law School. At Ann Arbor he waited on table and did clerical work in the dean’s office. Summers he ped- dled Dr. Chase’s cookbook, published in —A. P. and Harris & Ewing Photos. » English, German and Norwegian, price $1 to $3.50, depending on the binding; commission, 60 per cent. He cleared about $300 each summer. It was while peddling cookbooks that he met Miss | Lulu White at Albany, IIL When Burt Wheeler was graduated | o 2 | “straighten out” the Nordic neutrals as | & preliminary to the main action against from law school, in 1905, he was sent West by a physician who mistook over- work for tuberculosis. He established a law practice in the tough mining town | of Butte, after he had been cheated of | his small bankroll there. In two years he was doing well enough to go back to Illinois to claim his bride. | There was a large crowd on the Missis- | sippi River steamboat carrying him on the last stage of his journey. “There’s a wedding up at Albany,” the captain explained. “John White’s daughter’s getting married.” “Who's the bridegroom?” ventured. “Some damn’ book agent.” The Wheelers live in a sprawling white frame house in Washington—big because they have six children. Mrs. ‘Wheeler Wheeler likes to play nine holes of golf | with him before breakfast, to be sure | he gets his exercise, Has Few Intimates. but has few real intimates. He plays the game expertly with the Washington correspondents, with the result that he often gets the breaks in news columns | even when editorial pages are lambast- ing him. The Senator keeps up his law prac- tice. Borah complained when liberal | colleagues would not support his peren- nial bill to bar Senators from represent- ing firms which do business with the Government. - “The difference between Borah and me is that I've got six kids,” said Wheeler. Summers the Wheelers | 80 to a long cabin in Glacier Park. De- scribed by political opponents as “pala- tial,” actually it cost $750. Wheeler and his three boys buiit some additions. Montana is Far West. It is not popu- lous—has only four electoral votes. Yet Wheeler has a chence to win the Demo- cratic nomination. He has elements of strength, is acceptable to most New Deal- ers and not unpalatable to conservative Democrats. If the 1940 election is to be decided by three minority groups—farm- ers, organized labor Wheeler is in a powerful position. He John L. Lewis has singled him out for special political favor—indeed, he seems to be Lewis’ first choice for the presi- dency—and William Green has spoken highly of him. He is the darling of the railroad brotherhoods. He has demon- strated ability to get support from Re- publicans in the Senate. It is an outside chance. He knows it and is hedging his bet by seeking re- election to the Senate. That's the shrewd Yankee in him. It is a long shot—but long shots have won before. Strategic Nickel Mine Retained by Finns Reported undisturbed, despite the battles of the Finnish-Soviet Arctic front, is the Canadian-owned, $6,000,000 nickel plant of Finland’s Far North Pet- samo region. The end of the war, how- ever, has brought a third nation into the geographic picture. For cession to Soviet Russia of parts of the peninsular terri- tory north of Petsamo gives the Russians a strategic position overlooking the mines’ Arctic Ocean outlet. “Still in the construction stage, the mining concession held by a Canadian nickel company already includes a num- ber of surface works such as shops, store- houses and'workers’ homes, with & smelt- ing plant also well under way,” points out the National Geographic Society. “Pros- pecting in the region was begun in 1933. Operations,were scheduled to start in the fall of 1940, but the war slowed up activi- ties. “While the exact value of the nickel deposits has not yet been determined, it is estimated that the plant eventually will have a yearly capacity of some 12,- 000,000 pounds of the metal. Classified as a strategic war mineral, nickel durjng the World War of 1914-18 was especially useful as an alloy for armor plate and projectiles. Since the war, commercial demand for this metal has been heavy in various flelds. Nickel alloys are par- ticularly valuable in industrialand farm machinery, in mining supplies and trans- portation equipment. In other forms the metal is found in such varied prod- ucts as radio apparatus, jewelry, coins and decorative materials.” ‘ Wheeler is easy to meet, easy to talk to, | and Negroes— | Germans’ Scandinavian Success Spurs Italy’s Balkan Ambitions Hitler and Mussolini Seen Linking Territorial Aims by Striking Swiftly at Small, Helpless Neutral Nations By Constantine Brown. Whither Italy? This is the question on the lips of every statesmsn and diplo- mat in Washington and abroad. It is at the present time more important than the results of the military operations taking place in Norway and even more consequential than the impending threat to the independence of the Netherlands. There have been wishful thinkers ever since the outset of the war who actuaily believed that Italy would join the allies* it offered a fair price.. Many of the highest officials of our State Department believed this to be true. One of the tangible results of Mr. Sumner Wel voyage into Fairyland was to dispel this myth. He is said to have returned with the definite feeling that if Italy does not remain non-belligerent, she will certainly rather side with Germany than with the allies. The active war on the western front was decided by the Fuehrer after the historical meeting at Brennero between Hitler and Mussolini. According to the best advices which have reached Wash- ington, the two dictators reviewed the situation after it became evident that there could be no peace by negotiations and reached the conclusion that the | time to strike had come and that they must move swiftly. The chances of suc- cess were better than 50 per cent if the axis took the initiative at the present time—even at the risk of drawing the United States into the imbreglio in the next few months. This was felt not only by the diplomatic advisers of the two dictators, but also by the military men. Mussolini—who,is said to have a greater perception and “feel” of military matters —was all in favor of it. Norway a “Preliminary.” If the reports of what has happened at Brennero are correct—and there is more than a reasonable chance that they should be—Germany undertook to Britain and France on the western front and by devastating air attacks. The action of the Germans—these re- ports say—would be synchronized by an action of Italy in the south. It is rea- sonable to assume that the cautious Mus- solini is awaiting the final results of Germany's action in Scandinavia. Jjudgment of the situation is based not on rumors or demonstrations which the allies may make, but on hard facts and | results judged by the general staff. For the time being, Italy has given is about ready to enter the scene of and his henchmen and by notices in the government-controlled Italian press. But besides these public intimations of Italy’s intentions, there have been military measures which are sharply pointed. The Italian troops in the Alps have been so reinforced in-the last three weeks that the French had to increase their “covering” forces by another 150,000 men. More troops are held in readiness to be rushed to the Alps at a moment's notice. Field Marshal Italo Balbo's air forces also have been reinforced recently by the addition of an unknown number of airplane squadrons and mechanized units especially designed to operate in the sand dunes of Africa. But what is more important is the fact the Italian have reached the rendezvous in the Dodecanese Islands, with the Island of | | Rhodes as the main conceptration point. The presence of the whole Italian fleet | in the Eastern Mediterranean is a source of considerable worry to the allies. Greece Comes First. Italy, if she deciaes to abandon her non-belligerent status, needs a quick and easy victory. By a process of elimida- tion, the allies fear her first prey will be | Greece. This assumption is based on the the present time, an action against Tur- key by trying to force the Dardanelles. fying the natural position of the straits for the last five years, and they are con- sidered now as impregnable. It is equally unlikely that she will attempt a coup against the well-fortified and well-de- ‘fended Suez Canal. An action against Tunisia, with the important French naval base at Bizerta, is equally unlikely | on account of the prospect of a serious setback. On the other hand, the allies still be- lieve that in the event of & war develop- ing in the Balkans, their main base of operations would be at the important Greek port of Salonika and therefore they have done everything in their power to gain Greece to their side. That hav- ing failed, from the present disposition of the Italian fleet an attempt to conquer Greece seems more than likely in the event of Italy deciding to get into this war, Not only are the Italiari naval forces gathered at a point only 24 hours from Salonika, but in recent weeks important reinforcements—estimated at betwean 30,000 and 50,000 men—have been sent to Albanig, whence they could swoop down into Greece. It is true that the Italian government explained that the fresh troops sent into Albania were in- tended to replace battalions which had been there since the occupation of that country by Il Duce and had to be re- patriated, but observers in Italy have not seen as yet a single man retutn from King Zog's erstwhile dominion. Mussolini's Strategy. In military quarters it is considered that a coup against Greece by a com- bined sea and land operation is going 4o be attempted by Il Duce in the belig! that this can be done with impunity. The allies are deeply engaged at the predent.time in Norway. They are get- ting ready to intervene in the Low Lands in the event Germany decides to invade Holland and must be ready for a Ger- man attack against the Maginot Line. The British fleet is engaged in the North Atlantic and cannot spare impor- tant units for the Mediterranean. While British sea power is still supreme, there is no doubt that its striking force has been somewhat impaired since the out- break of the war by the loss of several units—either sunk or damaged. Because of the possibility of & German coup the French high command has dis- patched to the Mediterranean, since last | week, the units which were co-operating His | with the British fleet in the North At- lantic—the Dunquerque is rumored to be one of them. Whether the British have any impor- tant units in the Roman “Mare Nostrum | 1s uncertain. But Italy has a navy muc!: | larger and stronger than the German | fleet has put to sea for “spring maneu- | | vers” and was reported, on April 15, to | fact that Italy would not undertake, at | | The Turkish government has been forti- is the sponsor of three farm relief bills. | 5 L l the world enough indications that she | This fleet concentrated on one point is a serious match for the combined alliea conflict by speeches made by Il Duce | forces in the Mediterranean. The Italians have in commission &t the present moment seven battleships (three of the latest type and four re- constructed) as against nine French. B of the French ships several are old turs built 28 years ago. These have not becn modernized by the French. Italy’s Fleet Good. So far as cruisers are concerned ti > | Italians have eight heavy cruisers 15 | seven French, while the French have numerical but not qualitative superiori'y in light cruisers, having 14 such vesseis against Italy’s 12. The Italians have a definite superiority in destroyers (102) against the French (92) and the same thing applies to submarines, the French having 102 such vessels against 117 Italian. i The French auxiliary force is undoubt- edly reinforced by a number of British units, but because of the present opera- | tions it is difficult to ascertain how many. | The Greek Navy is of no consequence in | the event of an Italian coup agaihst that country. ‘There is no doubt that in the Mediter- ranean, with the British heavily engaged in the Atlantic, Italy is a first-class naval power which can boast to have at its mercy any country like Greece with a | long sea coast. In Paris and in London it is feared | that if the Italian government is con- l vinced that the Germans have been suc- cessful in Scandinavia—that is to say, | if the allied expeditionary force in Scan- | dinavia does not produce some tangible military results swiftly—there is more than an even chance that Italy will at- tempt to do to Greece what she has done _ to Albania, what the Russians have done to Finland, what the Germans intend to do to the Nordic neutrals. S e “I'm afraid yow've come at rather a bad time to dad. We've got slight artillery activity on the top floor i, see over the line, today” —By Bairnsfather.