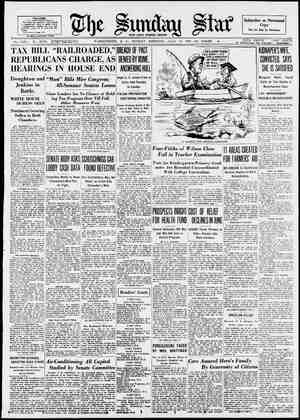

Evening Star Newspaper, July 14, 1935, Page 93

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

hS Magazine Section Puppy Love Continued from page two He saw her just as she saw him, and both hearts leapt high. In a minute she was in the shop talking excitedly to the proprietor. *‘He's back — the little black Scotty. I must have him, please. I have only thirty-two dollars, but I'll pay evety cent at fifty cents a week until the rest is paid. May I, please, sir?” To her surprise the proprietor im- mediately took the Scotty out of the window. “But be careful with him, miss,” he said. ““He’s inclined to be a little snappy.” “Oh no, never,” she defended, as if she had had him all her life; ““he’s very gentle.” He seemed gentler then than any creature she had ever known. And in her arms he felt a little lighter, too. He had eaten very little since she last held him, only enough to sustain life, but this Louise did not know. How could she, a mortal, guess the agonies endured by canines for their special gods? In the street he followed her like a veteran. She was proud and delighted. He himself had never felt so blithe and free. He sniffed every scent on the breeze and noted with wonder the strange new sights, keeping all the while close to her heels. But Louise’s joy was short-lived. She was wrestling with a grave prob- lem: how to break the news to her mother. For a while at least, she must conceal him. Perhaps she could hide him in her bedroom and take him out surreptitiously for exercise. Then she would broach the subject, coax a little, and perhaps her mother, seeing how much she wanted a dog, would say They came in unnoticed and went to her room. While Jock made an in- vestigation of the room and its con- tents, she prepared a little corner for him. Having found everything alto- gether satisfactory, Jock then obeyed her injunction to “lie down and be very quiet.”’ ‘While she mused her problem, there was a quick knock. “Open, please,”” her mother bade Louise’s heart beat furiously. She tucked Jock under the bed and opened the door, facing her mother with wide, frightened eyes. Sensing something unusual, Louise’s mother gazed about the room. Her eyes fell on a little black body pushing itself forward until it reached the comforting shoe of its divinity. “Mercy me,” she exclaimed, “‘a dog! So that’s where you’ve been.”” Louise struggled for words, but they did not come. The two stood staring at each other. Then her mother went out, murmuring, “I'll be right back.” Louise thought wildly, *“If mother won't let him stay, I'll not stay, either,” and she formed mad, bitter resolutions, and all the while her heart continued to thump so noisily that she could hear nothing else, not even her mother’s returning footsteps. “Oh, mother,” she said, close to tears, and got no further. “‘Here, my dear, if you're going to have a dog,” her mother said, in a firm but not ungentle voice, “you may as well learn how to bring him wp properly.”” For a long time Louise stood hold- ing the book. She was terribly happy, but she couldn't trust herself yet to show that she was. The pup, resting on her shoe, slept in peace. He had nothing on his mind now except to watch over his mew- found mistress. As long as he felt her shoe beneath his chin, he knew no harm could come to her. The Next War Continued from preceding page maneuver one another. Not until civili- zation decays, and it is no longer possible to mass-produce machines and to fuel them, will men again fight in primitive fashion, naively taught that the bayonet is the ‘“‘queen of weapons.” The traditionalists object that in- fantry is still the main element of military force, because infantry alone can “‘occupy ground.” But naval com- manders do not consider it necessary to “occupy” any particular wave — it is the relative positions of the opposing forces which matters. In- fantry in the land-battles of the future will have much the same importance as swimmers in the Battle of Jutland. Nevertheless, it is certain that this will not immediately be realized. Tra- ditions die hard. Assuredly, at the beginning, a muscle-power army will find itself pitted against a more or less completely machine-powered army. The commander of the machine-army will not be miles back, in a chateau. He will be in a fast-moving armored staff-vehicle, receiving aerial reports by wireless, giving his orders by wire- less, even as does an admiral. (A tech- nical battle to ‘“‘jam’” each other’s wireless will surely be a feature of the next war, as to some extent it was in the last). Armored, gas-proof whippet tanks, a couple of machine-gunners in each, moving across country at twenty miles or more an hour, will swarm around the flanks of the quasi-immo- bile, stiflingly gas-masked infantry, plunging easily across the slight trenches hastily thrown up in the course of a movement-battle. (An old- fashioned heavily entrenched position will of course be *‘turned.”) It will be a lucky battery which registers many hits on those cvasive, swift machines; it is amazing how even a heavy tank can avail itself of the lie of the land and be visible only for moments. Against such an onrush, in- fantry can do nothing and only the heavy armor-piercing machine-guns, difficult to handle, wguld be effective for the few minutes before their crews were slain in the streams of machine- gun bullets arriving from unexpected angles. Behind those swarming “‘whippets” will come the heavy tanks, armed with quickfirers that vomit shells, to deal with serious obstacles — even as the battleship supports the cruisers and the destroyers. Away around the rear of that impotent mass other light tanks will be racing across the lines of communications, shooting up local headquarters, spreading a chaos of disorder and dismay. Yet further in the rear, the side which has put its faith in machines, and therefore has superi- ority in planes, will be bombing the bases, the vast railroad sidings packed with supply trains for the front. Sedan will be only a miniature of the disaster which awaits the 19th-century army waging war against the technique of the 20th. However — and this should be re- assuring to the humanitarians — after the first masses have been sacrificed to the ancient jujus of plumed hats and gold braid, it is probable that military results — i.e., the imposition of the will of one nation upon another — will be secured at an infinitely less cost in human lives than at any time since the 18th century. Modern war, with its sheets of machine-gun bullets, its storms of high explosive and shrapnel, its mustard- gas which can make ground impassable to boots and shepherd the enemy into desired areas (hospital-filling mustard- gas is still the most effective muilitary chemical; the lethal gases are all too volatile), is of course appallingly deadly. It is so deadly, in fact, that no one can play at it who is not sheltered in an armored, gas-tight machine. But machines cannot be indefinitely multiplied in the fashion of man- power armies; they cost too much, and they demand too much fuel. Naval commanders think in scores of battle- ships and cruisers; they do not think in impossible thousands of ships. A victorious sufficiency is all that is required to impose acceptance of de- feat upon an enemy. Paradoxically, and logically, the more terrible that weapons have become, the less is their THIS WEEK pro-rata toll in human lives. In the Napoleonic wars it took a man’s weight in bullets to kill him. In the last war, it took a ton of explosives. In the next war, that tendency will be continued and accentuated. In that next war — unless, im- probably, Britain should side with Germany against France — there would seem to be little likelihood of major naval action. (A war for the mastery of the Pacific is specifically outside the scope of this article.) A war in which the British navy blockades Ger- many would be much like the last, save that the British battlefleet would be based much further off than at Scapa Flow. Then Jellicoe had only submarines to be afraid of. Now the British commander would have fast- flying squadrons of torpedo-airplanes and bombers as a constant menace. The best thing he could do would be to take his battlefleet out into the Atlan- tic. In the absence of any enemy fleet, it would have no function. But he could never forget that the biggest battleship, on which a heavy bomber has scored a hit, either direct or along- side, is no longer a fighting unit but — assuming it is still afloat — only a job for a repair shop. , A naval war in which Britain was engaged would be a desperate effort to maintain the continual flow of sea- borne traffic which is Britain's life- blood. That flow goes around the coasts of France,with its lurking shoals Farewell of submarines. So long as France was an ally the effort would probably be successful, despite the attacks not only of submarines but of aircraft. Against Germany alone, Britain could build up a defense as fast as the attack could develop. Only in the Pacific is a naval war likely to present any sensational features. To' conclude, the next war will not provide hundreds of miles of trench- lines behind which millions of men massacre one another in long-drawn futility. (It is inconceivable that Ger- many should attack the immense French system of fortification after the manner of 1914-18. It will be the bases of that system which will be attacked — by air.) However it com- mences, that war will end in the con- flict of small, completely mechanized armies, of which one eventually im- poses its will in the absence of effective Nor — unless the combatants let the air-arm get out of hand and smash one another into a chaos of anarchy — is that next war likely to be the end of civilization as is so freely prophesied. Whenever shivering pacifists make my flesh creep with that air-arm, I think of those Australian gunners and am comforted. Still, it might be worth while moving my very nice library out of Paris. Carlyle once remarked that the inhabitants of Great Britain were mostly fools — and that goes all over. Carlyle's compatriots had no monopoly. to Legs Continued from page eleven quivering at the memory, “with every ounce of weight and muscle behind the shot. I thought for a moment I had on, a more cheerful note creeping into her voice, “of breaking things in half, if you wouldn't mind, darling, just climbing that tree and handing me down its contents, I will see what can be done with this driver.” But Angus McTavish, who had been scanning the tree closely, shook his head. Gently he led her from the spot, and it was not until they were the distance of a good iron shot away that he released her and replied to the protestations which she had been uttering. “It is quite all right, dear,” he said. “Everything is in order.” “Everything in order?"* She faced him passionately. “What do you mean?”’ Angus patted her hand. “You were a little too overwrought to observe it, no doubt,” he said, “but there was a hornets’ nest two inches above his head. I think we cannot be accused of that when he starts to — ah!” said Angus. “Hark "™ peace of the spring evening. “And look,” added Angus. As he spoke, a form came sliding down out of the tree. At a rapid pace, it moved across the turf to the water beyond the eighteenth tee. It dived in and, having done so, seemed anxious to remain below the surface, for each time a head emerged from those smelly depths it went under again. “Nature’s remedy,” said Angus. For a long minute Evangeline stood gazing silently, with parted lips. Then she threw back her head; from those parted lips there proceeded a silvery laugh so piercing in its timbre that an old gentleman, practising approach shots at the seventeenth, jerked his mashie sharply and holed out from eighty yards. Angus McTavish patted her hand fondly. He was broad-minded, and felt that there were moments when laughter on the links was permissible. Christophine Discovers America Continued from page thirteen down. A lodge-keeper swung back a pair of wrought-iron gates which might have come from Versailles. The meter spitefully jumped another dime before the house came into view. When it did, my driver ground on his brakes with such sudden force that my head nearly snapped off. But at that he was only just in time to avoid a small open car of foreign make which flashed across our path like a humming bird, and, before our astonished, incredulous eyes, mounted the wide stone steps leading to the front door and went on into the house itself. Dazedly 1 descended from my taxi and saw that the big double doors of the main entrance were being held back by a pair of liveried footmen. The little roadster had been halted neatly about six inches from a cabinet con- taining what looked to be a priceless collection of Ming pottery, and from the driver’s seat, a tall red-headed girl emerged with a laugh of triumph. “I did it!"’ she exulted to a young man in riding clothes who sat astride the bannister, applauding languidly. *I told you that bus could climb like a fly"” “Well,"” said he mildly, “you didn’t break your fool neck, so I owe you five dollars"™’ At this point, the red-headed girl caught sight of me and stared coldly. Then a flicker of remembrance crossed her face, and she came forward. “I suppose you're Christophine Warren,” she said. “Come in, will you? I'm Miss Kattleburg.” Somehow or other I got up the steps and, entering the magnificence of that enormous hall, stood beside the powerful little car. It was all too fantastic to be quite real. My hostess made no immediate move, but stood looking at me intently. It was per- fectly evident that my appearance was not what she had expected, and that she was almost as much surprised by our meeting as I was. ““You brought a letter?” she said at length. I handed it to her silently. Some- how there didn’t, in that mad situa- tion, seem anything to say. Marcia took the letter uncertainly, but when she recognized the handwriting, her expression changed. She tore it open rapidly and read the first few lines. Then she turned to the men servants. “Take that thing away!” she ordered, pointing to the car. Then she spoke to the young man. ‘“‘Scram, Jack!” she said imperiously. The young man obediently began un- winding himself from the newel-post in a leisurely fashion, as Marcia turned to me. “You'd better come inside,” she said in a strained voice. ‘“This seems to be very important.” (To Be Continued Nest Week) ‘10000 PROTECTION Accigént Sickness e TeDAY You have happiness TOMORROW What? $10,000 }:::n;% $25 Weekiy tenent ‘ for Stated Accidents and Sickness | DOCTOR'S BILLS, Hospital | Benefit and other attractive fes- mtohalpywhthndud. GET CASH..not Sympathy! in case of automobile, travel, covered in this strong policy? PREMIUM $10 A YEAR Payable $2.50 dewn, balance in menthly payments Over 21,000,000 PAID IN CLAIMS A SUDDENACCIDENT! A SUDDEN SICKNESS! Canyou say neither will happen to you? ‘Then dom't delay another day. Pro- dent and Sickness Insurance Company in America. Send the coupon NOW for complete infor- mation about our NEW §1¢v PREMIER LIMITED $10,000 POLICY—and protect your family. , E Under direct supervision of 46 state insurance departments ® ESTABLISHED OVER 49 YEARS CO. (af Chicago) | 895 Title Bidg., Newark, ’ By RCRPONERER Ly, | no cost to me, ' mww 1 H ier Policy. There is no 1 . 1 = Name = 1 1 = Address = § City 1 |