Evening Star Newspaper, July 14, 1935, Page 85

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

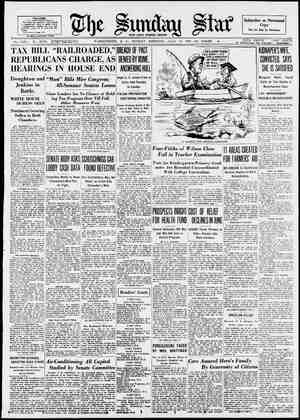

Magazine Section Illustration by 0. F. Schmidt SO & O 5 SHRILL whistle penetrated the in- fernal clatter. The stone crusher at Quarry Number Three slowed, slackened, stopped. Men in blotched blue overalls dropped their drills, shovels and jimmies, snatched caps and coats and made for the workhouse. Down at the Big Hole a huge, unshaven Italian fixed his windlass for the night, as Jerry and Porky emerged from the pit. ‘‘Been vera hot day, vera hot,” he ventured, wiping his glossy forehead with a huge ban- danna. attempting to grin at the men. If the two men heard the big Italian, they did not let on. They continued their hitching gait toward the workhouse. Jerry exploded to his fat companion, Porky, as he cranked the old car behind the workhouse: “We got a damn wop to work with! I told Steve our gang didn’'t want no more of 'em. We want Americans!"’ Porky seated himself on the front seat and stretched his legs. : “Can we say exactly we're 'Mericans, Jerry? We ain't got our papers yet, have we?’’ “Well, we're goin’ to, ain’'t we? And we're respectable, ain't we? We ain’t garlic eaters, are we? Say, Porky, did ya get a load of his breath this noon? I could hardly stand on me two pins.” Porky reached for his tobacco. “Thing that got me was the size of his paws. Gad! I never seen such paws. He sure can handle that windlass!” “And who couldn’t? I've seen lots could beat him. A wop with them hands ought to be luggin’ pig-iron, not twistin’' a rope!” “Wouldn't want to be on t'other side when one o' them paws gets riled up.” “Huh, he ain't so powerful as he looks. And he ain’t goin’ to last here. D'ye get what he said to me this noon?" “Sure. And 'twas half yer own fault.” THIS WEEK “Me own fault, Porky? What's ailin’ ya?" “Well, if ya hadn’t called him a wop, he wouldn't a said nothin’. D’ya think it was — well, policy — to call him a wop right to his face?' “That's what he is, ain't he? And he don’t go tellin’ me where I get off — not the likes of him. Who wouldn't say somethin’, when he brags how many kids he's got ?” “He warn’t braggin’, was he?"” “Sure he was! Braggin' he had nine of 'em. I told him it was a dirty shame.” “Now hold yer horses, Jerry, or they'll run off with ya."” “Hold me norses, me eye! That's what's killin’ the country — too much population. I told him so!”’ “Ya sure did, Jerry, and I see’d his big eves pop when ya said it. But I wouldn’t a said it."” “Well, he won't be on the job long, eny- how.” As Porky crawled out of the car on Roundy Street, Jerry told him he'd see Steve in the morning about getting rid of the wop. If Steve wouldn’t give ear, he'd have his say to the men. In the mbrning Jerry learned that Steve was not in a mood to let the new man go. “Tony’s the best I ever had on the engine. I watched him a dozen times yesterday. He handles them buckets and dumps 'em like nothin’ at all.” “‘But he ain’t a union man.” “He ain't got to be to dump rock in this “He ain't one of our kind. The gang won't stand for it." “I reckon they will, Jerry. The boys know jobs ain't hoppin’ at 'em any more.” “All right, then, have yer way, Steve. But I'm tellin’ ya there’ll be trouble.” Tuesday and Wednesday increased hostil- ities. Jerry got quite a lot of things otf’'n his chest, so he said, and Porky gave Jerry sup- port as frequently as support was asked. Thursday night Tony loitered around the quarry until the men had gone. He watched a pale strip of light shining beneath a frayed curtain drawn almost to the sill of the fore- man's office. Then he lunged around to the door, rapped and entered. “What is it, Tony?” The thick-set, black eyes burst into instant flame, his body began to shake. I get through. No good. Too much."” The foreman pushed a chair forward. *Sit down.” Tony only strode to the foreman’s desk, his feet shaking the floor, his heavy voice coming in gusts. “They no want me out there. Fight all time. No talk. No eat. No like. I go away. I say it is vera good day, and they say no good. I ask for ride home, and they laugh. I say to beeg fat man today, ‘How you feel?’ He say ‘Seeck,’ then tell me mind my damn bus’ness.” The boss sprang to his feet. “Now see here, Tony, you've got to stay. No good gettin’ all lathered up like that."” The huge Italian towered over the boss. “I no can stay. Make me seeck — all time tweest rope — tweest the rope. Nobody say ‘Hello, Tony; vera good day, Tony.’ One call me a damn wop. All laugh. I get through two days.” “You're a quitter?”’ “You mean Tony, he afraid? Tony, he keel them if he want to. Tony, he want work — and good friends.” “I didn't mean you were a coward. Just don’t let those scrubs discourage you. Why, you're the best engine man I've ever had!”’ “Yeu theenk so?” “Sure I do.” Tony relaxed. His eyes e softened and he held out s a hand. “Then may-be I stay.” “Thanks, Tony."” The following morning when the boss talked with Jerry and Porky and asked them to loosen up on Tony, the men moved off sullenly. Tony endured another day of loneliness and regret and reported for work Saturday morning as usual. Once again he ventured to remind Jerry it was ‘“‘a vera good day" and once more Jerry ignored the salutation, strut- ting unconcernedly by. Tony bent over his engine. Jerry wished he could be near enough to know what the big fellow mumbled. At ten-thirty Jerry and Porky cussed and 7 perspired, loading the rock into the bucket shoved them by the diggers. High up on the bank above, Tony waited for the signal. “‘Haul away!" Porky cut a circle in the air with his hands. Tony shoved a lever that started the clatter of the windlass. Slowly the bucket commenced to swing and rise, creaking, straining. Within ten yards of the top there was a dull snap in the machine, the engine shuddered, the wind- lass shot into reverse. Instantly the huge bucket of rock went plunging backward down into the hole. Jerry and Porky were bending over rock, directly beneath. Steve, a hundred yards to the right of the windlass, saw in a moment what had hap- pened, too paralyzed to move. He stood immobile, his features frozen with fear, while Tony, for an instant clawed madly at the lever, then shoved his arm into the grinding cog-wheels up to the shoulder. The wheels stopped. Down in the pit Jerry heard the terrific snap as the bucket of rock came to a stop not ten feet over his head. He looked up, then at Porky, pale, trembling, ghastly. The diggers, too, stared at the bucket of rock creaking into immobility, then at each other. Not a word was spoken. For an instant dark figures high above them were silhouetted against the blazing sky, clustering beside the windlass. As fast as they could, the men far down in the pit scrambled out, Jerry so weak he had to stop for breath three times during the ascent. Porky helped him up and they reached the bank just in time to pierce the crowd and see Steve ripping shirts off the men and wrapping them around the armless shoulder of a huge Italian uncon- scious on the 5 “God A'mighty!” groaned Porky, turning away. ““More shirts!" yelled Steve. ‘‘Help me with his shoulder, Mike. Go get my car, Charlie. For God's sake, hurry!” In three minutes Steve was rushing Tony to the hospital. Steve drove in front. In the back seat, Jerry held the Italian’s huge limp form in his arms and tried desperately to keep his eyes from clouding. All night Steve and Jerry waited in the They saw the bucket of rock plunging downward, Jerry and Porky underneath it \ " . 4 hospital lounge, paced the floor and exchanged bitter words. Early in the morning a doctor approached and motioned to Steve. A few low sentences were passed. As Steve, wordless, turned and started for the outer door, Jerry lurched toward him and grabbed his arm. “What is it, Steve?” Jerry's eyes were glassy, his stare pitiful. Steve shook himself free from the encum- bering hands. “Oh, nothin’. Wop's dead.””