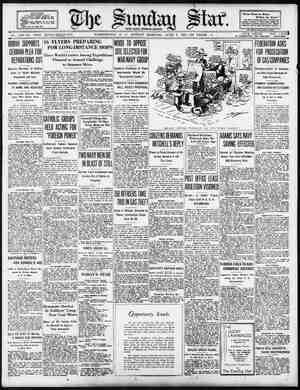

Evening Star Newspaper, June 7, 1931, Page 83

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

JINGTON, D. C., JUNE 7, "1981. H. SCHOOF. "\ was not released, but is here to tell of it. In Manother instance, though, the whites w:re less fortunate. AJ. WILSON and 40 volunteers, armed to the teeth, had set out through the wilder- ness one day to locate the main body of Loben- gula’s army. They located Lobengulu and his warriors at 3 o'clock one morning. The blacks were ali fast asleep, even to the guards, apparently after a long march. Maj. Wilson conceived the fool- hardy scheme of taking six picked men and a mule, slipping boldly to Lobengulu’'s tent and capturing that worthy. The plan almost worked. They got to the king's tent, which was easily identified in the bright moonlight, without. waking a soul. But just as they would have captured the king a dog barked. Then another dog barked, and then some more took it up. Shortly the black soldiers were up and in arms. The seven white men fled to their main body of 33, a mile or.so away. But they were soon surrounded. When the situation was seen to be hoprcless Maj. Wilson ordered two men to try to slip out and go for help. Among the volunteers was one Fred Burnham, later Maj. Burnham, who today is California park commissioner, residing at Los Angeles, and who unquestionably is one of the greatest scouts that ever lived. Burnham got through and came back next day with help, too late. They found 500 dead blacks and 40 disem- boweled whites, The Matabeles had surrounded Wilson's party, pounded shields and spears, hummed their weird chant, and marched in to annihilate them. In the last minutes—so the blacks told us Jater—when only six of the whites were left standing, they ceased firing, removed their hats, and there in the African moonlight sang one stanza of “God Save the Qu2en.” The blacks, astounded at this move, ceased fighting too, and stared agape at the white men until their song was don2. Then they charged in and climaxed the drama with their own gruesome benediction. DURING that war 4,000 of us white soldiers were pitted against 20,000 blacks. (Our original 500 was later augmented.) I suppose we killed at least 10,000 of them in hand-to- hand combat. Many of them were well trained men, too, and we had a price to pay for ultimate victory. Our men had to be good to stick it out. Once a band of white soldiers was captured, 25 white dragoons. Three of the British scouts, detailed to try to figure out a way to aid them, could do nothing. Al night they heard the 25 men screaming, screaming, and were powerless to help. They dared not go too close, for they knew the blacks would only add them to the tortured group. 3 Next day, when more help came, the whites (. “Dancing with delight, the black raised his long spear for the final thrust. I was helpless to prevent it. Then Pat O’Connor jumped 10 feect or so and landed bnyonl’l first. found their 25 comrades in the ce- serted Zulu camp, ali of them neaily skinned alive, their skins hanging nearby. It was a favorite trick, too, for the Zulus to capture three or four whites, tie them spread-eagle fasi- jon on the ground, nude, and place live ccals on their bodies. This afforded much around-the-campfire hilarity for the blacks. For variety's sake the blacks might tie an un- fortunate captive near an ant hill and pour honey on his body. And some of tice African ant hills get to be 12 feet high, so denscly populated are they. African ants, by their sheer num- bers, can kill elephants or any cther beast, and fre- quently do so. Thev are the scourge of the jungie. ND so, you see, we who were in the mounted police or the British Army of the South African campaign have little affection for the Zulus. Too many memories. Too many first- hand experiences of savagery and cruzity. King Lobengula one year was making prep- arations to start plundeiing the peaceful agri- culturists to the south of him, ruled by one King Khama, a Christian black man. Khama had appealed to the British for help. The British had established a protectorate, and it fell my duty to escort Dr. Moffat, brother-in- lJaw of the famous Livingston, into Bulawayo, where he was to present an ultimatum to Lobengula, a warning not to molest Khama if he wanted British friendship instead of Bitish enmity. 1 traveled with Moffat for days and days. We developed fever and dysentery. We suffered hunger. Our horses were skeletons. Lob:2ngula knew of our coming, in fact he had promised us we could come in and leave safely. But his huge black warriors formed a long lane for us as we marched toward his “palace,” hideously painted, naked warriors all anxious to kill us. We were presented to the mighty King as he sat on a throne of elephant tusks and lion skins. He wore a lkopard skin coat, had ostrich feathers in his headdress, rings in each ear and around his neck. In an intimate family semi- circle about him were his 67 wives, each weighing from 200 to 400 pounds. Fat, there, is a mark of feminine beauty. Moffat presented the British Queen’s ulti- matum, and old Lobengula roared in arrogant laughter. He called our attention to a kraal made of elephant tusks, big enough to hold 1,500 cattle, an ivory stockade worth a fortune. He pointed to the forest of posts, each topped by a human skull, 'which adorned his courtyard. He showed us these to impress us, and said he would do as he pleased, would attack Khama soon, and if the white soldiers there got in the way his war- riors would kill them too. We departed, wondering if we could hope to get back to headquarters safely. Frankly I doubted if we would. What if the King had promised us we could return unmolested? = He hated us, told us so, threatened us with death if we crossed him. UT I had not counted on a black King's sense of honor. I learned that Lobengula’s word was law, absolutely. We had potent proof when an elephant hunter secured permission to hunt on his lands and subsequent events prompted Lobengula to give us a demonstration of his integrity. The hunter had been promised immunity from harm by the King. But the foolish white man, staying one night at a black village, got drunk and the black villagers killed him. Promptly King Lobengula roared in anger whsn he heard of it. He thundered, “Is that the way a King keeps his word?” And he caused the entire village of 250 men, women and children—his own subjects—to be killed as punishment. I never doubted him again. I tell you this so you may have a better conception of the type of men we fought in Africa. They were an ignorant and cruel lot, and fighting them was a bloody pastime. W here “Maj. Schoof” was executed during the World War. The Tower of London, in which the death of a German spy led to an odd mixup involving Maj. Schoof's name. On top of all that, we in the Bochuanaland Mounted Police had all sorts of nalural hard- ships. For days I have lived on grasshopper hash, with an occasional bowl ¢f monkey soup. I had thought, back in the days when I was assceiated with old Chief Sitting Bull in the Dakotas, that dog soup was my Lmit. I learned better in Africa. We also had to face some dangerous reptiles during our service in Africa. I rccall the case of Trooper Todd, who had just been discharged from the service and was about to d t for his home in England. He was as happy s ever a trooper gets, laughing and carefree, in that last camp. We were encamped on the banks of the famous Limpopo or Croczodile River, rizhtfully named. At dawn Todd arose and started to wade into the river to wash his face and hands in the shallow water at the shore. “Todd, don't go into the river!” I shouted at him. “It’s full of crocs. They've been watching “Who's afraid of crocodiles?” he sang back, and waded in almost waist decp. The next instant he was sercaming for help. We rushed to the bank in time to sec his head and waving arms go under, then the spot was just a ripple leading up stream. It was the last we ever saw of him. In time my enlistment in Africa ended. and 1 was a bit homesick for America. I drifted back westward, but quite naturally entered military service again, this time in the 23d Alberta Mounted Rangers and later in the Canadian Provincial Mounted Police, of which 1 am today the oldest active member. IGHT here I want to prevent any possible misunderstanding by pointing out the dis- tinction between the Provincial Mounted Police and the Roya] Mounted. An easy way of making the distinction is to say that the Pro- vincial Mounted are somewhat like the Texas Rangers in the United States, while the Royal Mounted are more like American Federal offi- cers. The Royal Mounted, incidentally, not infrequently get the credit for things the Pro- vincial Police do. The provincials are my crowd —and a good crowd of active, capable police they are, too. However, I am getting ahead of my story. Before I finally settled down to an extended Chopping block for spies and trai- tors in the execution room of the old Tower of London, where Maj. Schoof was never confined, in spite of the wewspapers. career with the Provincial Police, I wandered down to Texas, locking for excitement. Being near the Mexican border, 1 was invited to cross over to the Mc:cxican side and deliver a speech. I did so. and found among my audi=- ence non2 other than Fiancisco Maderd, then President of Mezxico. At the end of my talk President Maderg in- vited me to join his stafl as instructor in swordsmanship and fighting for his Rurales, The Rurales were the Mexican federal police— a body organized originally by Diaz, somewhat similar to the Texas Rangers and surprisingly efficient. The invitation looked attractive, and I accepted. The Rural:s nceded instruction, for though they all carried machetes they could not use them expertly. However, they learned rapidly, Mexicans love to fight with knives, perhaps because it appeals to their romantic and fiery natures. The job didn't last so very long, however, In the course of time one of Madero's officers, Victoriano Huerta, sold out to Madero's enemies and enginecred a coup that resulted in Madero’s assassination and Huerta's elevation ta@ the presidency, where he had a turbulent time of it. S a result, we who had been Madero's fas vorite officers found ourselves in a bad situ- ation, and presently I was lodged in jail, along with several others, sentenced to be executed by a firing squad. I suppose my poor fellows in jail were killed as ordered, but when the time for execution came I began talking. You know, a gift of gab is a lot of fun some- times, and if properly used it may be highly valuable, too. I told them I was a British sub- ject, and suggested that all of his majestye army might be landed in M=xico soon, in spite of the Monroe Doctrine, if I was executed. Furthermore, I hinted that I could get my bands on $40 in actual cash, under proper circumstances! The two suggestions worked. I was fined $40. And here I am, able to tell about it. As I re- marked before, a gift of gab and a little extra cash are a lot of fun sometimes, and may be highly valuable too! Here in Canada in the Province of Allerta I have been in the service of law enforcemens$ almost ever since, and I am today the oldest active member of the Canadian Provincial Mounted Police. We in the frontier police work find that we do not have to dash hither and yon about th@ world searching for adventure. We seldom haw@ a “war,” to be sure, and we never have a Villa and we never have to combat naked Zulus with shields and spears. UT the Canadian provinces have some wild country, and some wild characters moles§ them. Taking them is no child’s play. Much of Canada is still a frontier land, strictly speaking. It is to this arsa—made still more glamorous in fiction and pictures—that many lawless folks gravitate. We must—Iliterally must—maintain a high standard of manhood in the police. Hence it is an honor to be a member, and we are proud of it. We do not say it boastfully. We simp@e believe our pride in the force is a justifiable one, and every man’s sense of duty is heightened because of it. When the World War came along I could not serve in actlie fighting. I had lost some of my physical periection due to bullets and spears and clubs in Africa, and had been more recently injured when a horse fell on me. But it was not difficult to find something to do to serve the allied armies in the war. I had an abundance of work at home. The war had to be financed. I sold bonds. I teok part in almost every sort of home activity, and I had as much satisfaction, if not as Continued on Fourtecnth Paae