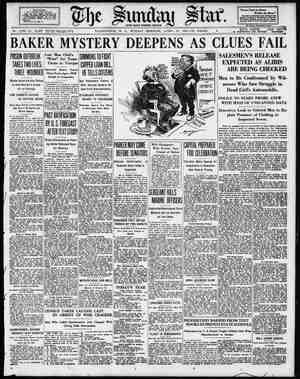

Evening Star Newspaper, April 20, 1930, Page 87

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

BY ALICE HUTCHINS DRAKE. HE Easter season finds thousands of visitors to Washington eagerly ex- amining the mural decorations in the Library of Congress. One of the two most popular series of paintings is *“The Evolution of the Book,” by John White Alexander. To use the phrase of John Erskine, the art- ist has here “set to painting” a great drama. The casual visitor finds sufficient to give him pause when he examines the Alexander murals ‘The book lover, the one who holds in reverence the Printed Word, ls a sense of awe as he studies the develop'fjent of the theme as por- trayed by the hand of the painter. John White Alexander is ranked by many art critics as one of the four of America’s greatest artists. In fact, some years ago he was one of the group popularly called “the . big four,” the others being Whistler, Sargent and Abbey. Each man is represented in Wash- ington, in the Library of Congress, Freer Gal- lery of Art and Corcoran Gallery of Art, respec- tively. The Alexander murals are in one of the three largest libraries in the world. It is said of them that few murals in this country are ap- preciated by as many people. HE series comprises six lunettes. On the south wall is, first, “The Cairn.” In itself, the word “cairn” is interesting. It is a Celtic term meaning an artificial heap of stones. In Alexander’s mural a group of skin-clad men is assembling the conventional conical pile of stones, probably to record some historical event; possibly to indicate simply that they have passed along this “rock-bound coast.” In the second tympanum a professional Arab story teller holds enthralled a group of seated listeners. The pose of the Arab, in his flowing white robe, is especially striking. He stands with one hand grasping a long pilgrim staff. His right hand and arm are outstretched, a slender forefinger pointing to a distant wall. Here is one allied in spirit to the troubadours and to the trouveres; to the minstrels of a later day; allied also in spirit to the profes- sional story teller who even today continues to spin fantastic tales in the market place, in bazaars of far-distant lands; allied in spirit to those who send out the spoken word by radio. Adjoining this panel, the title of which is “Oral Tradition,” is one which has for theme, *“Egyptian Hieroglyphics.” A young artisan is executing sacred carvings on the wall of a tem- vle. T. George Allen of the University of Chicago, in writing of hieroglyphics, comments upen the fact that “hieroglyphics proper, espe- cially as used on tomb or temple wall, were in- tended as much to decorate as to inform.” Over the entrance to the temple in Alexander’s mural, a scaffolding is swung. Here sit the young workman and a girl companion, In the distance flows a shallow Nile. Beyond is one “Festival o ASTER is the oldest festival known to mankind. It was instituted by Nature, herself, and was originally celebrated in honor of the Spring. Primitive man could not fathom the Spring miracle, but he could appreciate it, and celebrate this joyous “Festival of breaking bud and scented breath.” Every nation had its own name and legend for Spring—the resurrection of life. Each year, when Nature lived and blossomed anew, the tender beauty of the flowers stirred the human mind to wonder and deep speculation. Litera- ture is rich in beautiful legends of the flowers, which tradition says first bloomed in Heaven. When the evil angels were driven from Heaven they snatched their arms full of flow- ers and carried them away. But God would not permit His celestial blossoms to be taken to Hades, so He caused the wicked angels to become tired, and, one by one, they dropped the flowers over the earth before they reached their destination. Another old legend which accounts for the beginning of the flowers states that Venus sprinkled nectar into the blood of the wounded Adonis and flowers sprang up. The word flower itself comes from Flora, the ancient goddess of flowers. Although the flowers were originally connect- ea with pagan customs and beliefs, most of them are now closely woven, by Christian tra- ditions, to the event of the resurrection of Christ. OF all the flowers that open in the Spring none so beautifully typifies the religious sentiment as the lily. The Easter lily has be- come the symbolic flower of the resurrection of Christ. Once it was known as the Persian Beauty, but tradition tells us that the flower turned from yellow to white as the Virgin plucked it and held it in her hand. It is also known as the Fleur de Marie, the flower of Mary. Dante spoke of the Easter lily as the lily of the Arno. Tasso called it the golden lily and Solomon sang of the “lilies of the field.” St. Joseph’'s staff budded and lilies bloomed forth. In all ages and lands the white lily has been closely associated with the two greatest mys- teries of human life—birth and death. Juno, the Queen of the Roman gods, chose the lily as her symbol, and the classics tell us of feasts given among the lilies. Joan of Arc was crowned with white lilies to typify the purity and sa- credness of her mission. The first lily used as a symbol of the re- surrection was the Madonna, or Annunciation lly. The early masters have used this lovely "'y in their pictures of saints, angels and the Madonna. In the Madonna pictures there are frequently three lilies on a stem to represent THE SUNDAY STAR, WASHINGTON, ‘B. €, TAPRH; 120> 1930.- Crowds View “E The Printing Press, by John W hite Alexander, Library of Congress. Easter Brings Many Visitors to Library of Congress to See Famous Mural Decorations of John White Alexander, Who Is One of America’s Four Greatest Painters. of the Pyramids. This painting concludes the first group of three lunettes. The theme, “The Evolution of the Book,” is resumed at the north end of the corridor. The first mural symbolizes the pictorgraphs of the American Indian. From the standpoint of the painting it arouses perhaps the least interest. This may be due to a number of causes. One of the best-loved paintings in the Library ad- joins it and instinctively the visitor turns to it. Pictorially the panel, “Picture Writing,” is much less effective than most of the others. Here is a sandy waste, upon which is stretched the skin of an animal. A young Indian is paint- ing upon it. Beside him is a young companion, a girl, who watches him as earnestly as does the Egyptian girl watch the hieroglyphic cutter in the corresponding tympanum. It is probable that the chief reason for the absence of re- sponse to this painting is that the average American knows little about the picture-writ- ing of the American Indian. 2 fascinating subject. It is, however, If one does no more than read a paragraph or two in that extraordinary book, ‘‘Hodges’ Handbook of th: American Indian,” he gains enough information to add materially to his appreciation of the Alexander mural. “Picto- graphs,” says the authority just mentioned, “have been made upon a great variety of objects, a favorite being the human body. Among other natural substances, recourse by the pictographer has been had to stone, bone, skins, feathers and quills, gourds, shells, earth and sand, copper and wood, while textile and fictile fabrics figure prominently on the list.” Later the writer adds that dyes of various shades of brown, red and yellow which were extracted from plants were available for paint- ing. In the library mural the Ingian pictog- rapher is painting on a deer skin. Nearby is a saucer containing red coloring matter. A HAND at work creating beauty—a hand that opens vistas for mind and spirit—is found in the next painting. The setting is - o | 15 — volution of the Book” Paintings the scriptorium of a convent of the Middle Ages. George Haven Putnam, writing in “Books and Their Makers During the Middle Ages,” quotes the words employed at the consecration of a scriptorium as “evidence of the spirit in which the devout scholars approached their work™: “Benedicere digneris, Domine, hoc scriptorium famulorum tuorum, ut quidquid scriptum fuerit, sensu capiant, opere perficiant.” (“Vouchsafe, O Lord, to bless this work room of Thy servants, that all which they write therein may be com- prehended by their intelligence and realized in their work.”) In the painting light is admitted through a small window in the upper left wall. In the left foreground sits a monk garbed in white. Before him is a drawing-board or bookstand, over which he earnestly bends. Seated before the "wall in the background is a second monk, beside whom stands a third. They are work-' ing at a table, possibly in roles of illuminator and corrector. Frederick W. Hamilton, in dis- cussing the “Making of Manuscripts,” reminds us that “the makers of manuscripts, particu- larly during the Middle Ages, took enormous- pride in their work and were as anxious to_ produce sumptuous books as the most ambitious publisher of today and were often far more successful. The scribe who was to make a fine manuscript chose his vellum with great care. He laid out his work with compass and ruler with the utmost precision. He was careful that his ink and his pigments should be of the most brilliant color and the finest qultlity. He looked well to the care of his pen and inscribed each Jetter with the patient care of the most skillful engrosser of today.” One is tempted to lingef before this mural, absorbed in calling to mind all that he has known concerning the art of making illuminated manuscripts. And assuredly there is much to know! Tradition says that a knowledge of paper and of papermaking came into Europe by way of Spain after the conquest of Samarkand by the Arabs in 751. This knowledge, the invention of inks suitable for use in printing and the adaptation of a simple press to the needs of the book+ maker hastened the end of the day of the manuscript. History does not definitely record - who invented the inks first used by Europeans in printing. One story is to the effect that the painter Hubert van Eyck was the inventor, Similarly there is doubt as to the actual in- ventor of movable type. So far as the artist John Alexander was concerned, the controversy was settled. In the last lunette of his series, “The Evolution of the Book,” light floods from the ceiling on a large man who stands looking at a page eagerly grasped in both hands. Close by is an elderly assistant who bends low, the better to see the miracle. To the right is a printing press, a young apprentice swinging upon it. The figure which dominates the group is Gutenberg. He it is who stands gazing at the first page pulled from his press. The printed word has become reality. ) Breaking Bud and Scented Breath” the trinity, or the annunciation, conception and birth of the Savior. A pot of these lilies over doors and windows is symbolical of the Virgin in ecclesiastical art and architecture, but lily pillars, or columns, typify the resur- rection. In modern times the Easter lily has taken the place of the Madonna lily both in America and in Europe, because it is a hardier plant. The Easter lily, or Bermuda lily, was originally a native of Japan. More than 200 years ago a pirate sea captain brought some of the bulbs to Bermuda, where it grew larger and more beautiful than in the Orient. It became known as the Bermuda lily, and for generations its care and cultivation were handed down from father to son, until it became one of the house- hold gods of the island planter. Until very re- cent years America was entirely dependent upon China, Japan and Bermuda for bulbs of the Easter lily, but through painstaking experi- ments the United States Government has learned to produce our own bulb supply. Not only the Christians, but all other re- ligions of the world have used the lily to typify consolation and hope. The lotus lily is sacred to the Buddhists, and to it they dedicate cease- less prayers which are printed on parchment and fastened to constantly revolving cylinders in the great temples of Thibet. From Egypt to China superstitions and great love abounds for the sacred lotus. Tradition also relates that Judith, the Israelite heroine of the Apochrypha, wore a crown of lotus lilies when she went upon her mission to destroy Holofernes. And all the world knows that Cleopatra wore lotus blooms in her hair. THERE is a lcgend old as Christianity, which says that the Virgin spilled a few drops of her milk on the ground, and from these drops sprang the dainty little lily of the valley, those “fairy bells that bring incense to the Spring.” But in some of the old English country vil- lages this precious little flower is called the Ladder of Heaven. The ancient Druids be- lieved that it symbolized future happiness, and they used it at weddings to insure wedded bliss to the bride and bridegroom. In the old days all marriages were celebrated in the Spring, about the time the lily of the valley bloomed. Few modern brides rcalize that they follow an an- cient pagan custom when they carry a bridal bouquet of lilies of the valley. The Calla lily can claim one of the most beautiful legends of all the flowers. When Christ drank from his cup at the last supper it was changed into a beautiful chalice-flower —the Calla lily. This llly was destined to bloomh alone in its purity. Tradition says that :su;ernmmenolyonuhuneverbeen ound. In the days of dim antiquity all flowers were divided into two general classes. The bell- shaped blossoms were called lilies and all the others were roses. This is said to account for some flowers being called roses which do not belong to our present rose family. The rose of Jerico is one of these. It is not a rose at all, but a sort of vegetable. This plant is sometimes used as a symbol of the resurrection because it is usually found in a shriveled, dried- up condition, but it is immediately revived or resurrected by a little moisture. However, the rose of Jerico is more commonly called the rose of Mary because tradition says that it grew to mark every resting place of the Holy Family during the journey to Egypt. ANO’I'HER flower of the Easter season, the primrose, is likewise not a rose. Its old generic name in primula—or first—and since it was not bell-shaped it was called a rose. This flower blooms so early that it has become the symbolical flower of the month of January: “Primroses, the Spring may love them, Summer knows but little of them.” The briar-rose, according to ancient Chris- tian tradition, grew from the drops of blood that fell to the earth from the Saviour’s brow when it was pierced by the crown of thorns on the cross. But there is another legend which says that Christ's crown of thorns was made of the white briar-rose itself, and the red rose sprang from these blood-stained roses: Men pierced his brow with thorns, but Angels stanched his blood with roses. To this day the faithful in some parts of Russia will never suffer a red rose to lie on the ground. The red rose is usually considered an emblem of the crucifixion, but the white rose belongs to Mary. She dried her mourning veil on a rose bush and the bush bore white roses ever after. Cupid gave Hipprocrates, the god of silence, a rose, and that flower has since become the symbol of silence. When the Greeks wished the conversations at their feast tables to be kept secret a freshly-gathered rose was hung from the ceiling just above the head of the table. It was considered dishonorable and even criminal to reveal anything said “sub rosa,” (under the rose). But the mythical blue rose is symbolic of heavenly bliss and unattainable earthly ideals. The passion flower got its name from the fancied resemblance of certain parts of the flower to the instruments of the crucifixion. It is also a symbol of faith. The evil mandrake which is found in South- ern Europe, North Africa and Aisa Minor is also bound by tradition to Easter. Only a$ Eastertime does the devil lose his power over this herb. The root of the mandrake resembles the human form and it is said to drip blood and shriek terribly when dug from the ground, It was thought to be poisonous—even nare cotic. Many and strange are the supersitions related to it. It is said that it first grew bee neath the crosses of the two thieves who were crucified with Christ. But in Genesis we find that Leah used it as a sort of love charm to attract Jacob. . In Iceland there is a quaint Easter supere stition about this weird root. If one wishes to become suddenly rich—and who does not-— he must possess a mandrake root and steal a coin from a poor widow at early mass on Easter Sunday. When the stolen coin is placed beside the mandrake it will, mysteriously and immediately, draw all coins of like denomina= tions to itself from every individual's purse in the church. But the root can only exercise this magic when it is dug from the ground on Good Friday before sunrise by a man with a sharp sword and an undesirable black dog. Sue perstitions say that the terrible shrieks of the uprooted herb will immediately kill the black dog and therefore save the man and bring him luck and fortune. Joan of Arc is supposed to have carried at all times a female mandrake possessing great magical powers. s 'HE poets have always loved the dainty Ifttle Spring violet. The large early violets which bloom on the banks of sterams and in marshy places are a true violet color, although they are sometimes said to be blue or purple, Shakespeare says, “The violets blue do paint the meadows with delight! The Ionia Athee nians were proud of the violet and they used it lavishly in their architecture and art. It was as prominent in old Athens as the rose of England and the lily of France are in those countries today. Violets were for sale at all seasons in the public market places of Athens, The Greeks called this little blue flower Ion, for the goddess Yo. When the unhappy Io was changed to a heifer Jupiter was saddened at the thought of her eating common grass so he caused violets to spring up in place of grass wherever the lovely white heifer bent her head tc graze. The violet was the favorite flower of Mahomet and the ancient Arabians admired it greatly. Napoleon loved this mode est purple flower above all others and it became the emblem of the Bonapartists, who, remem- bering Shakespeare’s proverb, “The violet is for faithfulness,” still wear it as a token of a lost cause. No legitimist in France will ever wear violets. This flower is symbolical of the month of March. >