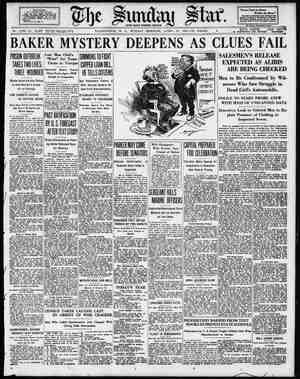

Evening Star Newspaper, April 20, 1930, Page 84

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

VOICE is calling your name, and you rise reluctantly from a deep well of sleep. It is dark in the cabin, but moonlight shines blue outside the window. Framed in the bright rectangle of the open dcor is the silhouette of a man’s figure. “Who is it?” ycu call. “Dis is Henry,” the voice answers. “I done come tuh tek yo' to chu'ch.” “But it’s the middle of the night,” you protest. “Yassuh, it sho’ is—but we-all starts long befo’ day, an’ de chu’'ch is a long ways off from heah.” It is Easter morning on the plantation in Louisiana, and in a far-off church in the woods the Negroes are gathering for a sunrise service. Henry has come to take you with him. And now, as he ad- vances into the rocm you see that he carries a steaming coffee pot in his hand. The hot, black drink drives sleep from your eyes; you rise by yellow candle light and begin to dress. Outside you can hear the stamping of horses. Ten minutes later you are in the sad- dle, following the Negro man who rides before you. The big house of the plan- tation seems sleeping among its trees, with moonlight slanting across its white columns. Mist hangs low over Cane River, and the foggy fields are like great bowls of milk. We gallop down the river road, two ghostly riders. After a mile, we leave the road and strike out across a cotton field toward the woods beyond. A cool breeze is blowing, and you can smell the swamp. In the stillness an owl calls, and your horse pricks up his ears; Henry shivers and turns his hat backward to ward off bad luck. THE woods loom ahead, a dark wall. Festoons of Spanish moss are lighter among the shadows. The moonlight does not penetrate beneath the trees. Henry curbs his horse and turns abruptly into a trail which leads into blackness. You can see nothing and ride with your arm raised to protect your face from therns and branches. From time to time the man ahead calls back a warn- ing of a low limb or of an entangling vine. The two-mile ride through the woods seems endless, but it is over at last. Ahead lies a clearing, with moon- light slanting down on white rectangu- lar stones. A cemetery. We slide down from our saddles and tie the horses to the graveyard fence. The dark spire of the little church leans crazily against the lighter sky. It is black under the trees beside the church, and you can see nothing, but the darkness is alive with voices: “Howdy, Mister Henry!” “Mawnin’, Sis Viney!” “Is de songsters come yet?” Here and there the burning end of a cigarette or the wider glow of a pipe shines for a moment and fades again. There are many Negroes waiting here; you can feel them all arcund you, al- though you cannot see them. An old woman’s voice comes from the dimness at your elbow: “Mawnin’, Mister Sack. How you do?” “Who is it!” you ask, laughing. “I can’t see you.” “Lawd-Gawd!” the vcice replies. “Is I so black yo' can’t see me? Dis is ole Aunt Patsy.” You greet her warmly, for she is an old friend. She is the Cane River wise woman and midwife, and her spells and charms are famous for miles around. Her grandchildren are legion. Now, as she greets you, she puffs deep on her pipe, and for a moment you can see her wrinkled face below her white head- handkerchief. The crowd is moving toward the church door, and Henry takes your elbow and pushes you ahead of him into the inky blackness of the building. You feel the smooth backs of the benches under your groping fingers, find an empty pew and clide in, moving over against the wall. The windows are open, and the dying moonlight is pale beyond them. The Many spend the entire day at the church. .dark hour before daylight is wpon us. Within the church you hear ‘t’ie scrap- ing of feet on the bare floor, and a dog velps suddenly as some one steps upon it. There is a murmur ¢! whispering voices. After a time there comies a profound hush, and out of the stillness a woman’s voice rises in a mournful chant : Oh, guilty, guilty my mind is, Oh, take away de stain. . . . A DOZEN women’s voices take up the melody and a chorus of men’s voices hums accompaniment, deep and mellow. Only two lines, repeated over and over, then silence again. But now the darkness is filled with emotion. A woman sobs aloud, a sob which is muf- fled immediately. There is a moment of expectancy, and then a man’s deep voice begins to speak: “Please, Jesus! OH, please, Jesus!” Twenty voices call out in response from the blackness: “Hab mussy!” “Lawd, help!” “Oh, Jesus!” And then the man’s voice goes on again: “I want You to tear down de wall. Teach our feets to know de way for peace. For peace. Forever-lasting peace. Oh, Jesus, we-all goin’ tuh ask ole Aunt Palsy to pray for us.” ... There is a stir and a sound of foot- steps; then the old woman’'s voice is heard: “Oh, Lawd! Tt’s wid a pure heart Ah come tuh Yo’ dis mawnin’! I pray an’ I pray. Oh, Lawd, Yo’ done heard me pray, and now Ah wants Yo’ to heah us all pray. We wants Yo’ to comeé among us dis mawnin’, Lawd, an’ let Yo’ light shine upon us. Lawd, Lawd! We is wanderin’ 'round in de dark, and we needs Yo’ to come an bring us de sun- rise and let us see how tuh walk in de right road. Oh, we needs Yo’ bad, Lawd! We needs Yo' bad!” And from the congregation comes a chorus of assent: “Dat’s right, Lawd! Jesus, help! Hab mussy!” Then, with a strangled sob, the old woman’s voice cries out: “Jordan, stand still and let me cross ovah!” N the pause that follows there is a sound of sobbing. Soon a low hum- ming is heard, then a woman’s voice be- gins a hymn. It is the old familiar THE SUNDAY STAR, WASHINGT( Laster on the Plantat Drawings By E. H. Suydam For In This Story the lous New Orleans,” ¢ pi” and ““Old Louisia ful Description of Customs of the Old Sq tation Colonies at Eas melody, “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” and in the darkness it rings out with almost unbearable beauty. Many are crying now, and there are frequent shouts of “Hab mussy, Jesus, hab mussy!” The moonlight has faded out and the black- ness surrounds us. And then a new voice is heard. A man’s voice, rich and soft. The sermon is beginning: “The chu’ch is throwed open dis mawnin’ an’ we done come a long way from home to git heah. Heah we is, lLawd, heah we is!” The cther voices interrupt: “Yes, Lawd! Heah we is, Lawd! Look at us, Yawd! Lawd help!” This preacher speaks again, this time with a strange rhythm: “Once a yeah we leaves ouh houses while it is still dark, Lawd! Once a yeah we come heah to dis dark chu’ch. We leaves ouh houses an we comes to Yo'.” His voice becomes a sing-song chant: We comes a long way . .. Through de woods an’ ’'mongst de trees. We comes slow, slow, but we comes. Cause we been thinkin’, Lawd. Yes, thinkin’ ’bout Resurrection. Is is Easter morning on the plantation and the