Evening Star Newspaper, April 20, 1930, Page 75

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

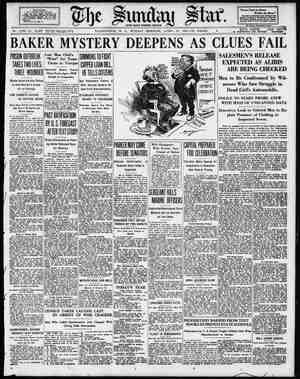

In the first article Lseut. Col. Mil- ler described the consternation of Paris citizens when, on Saturday morning, March 23, 1918, shells be- gan to drop into the csty. The sec- ond one struck mear the heart of town and killed several. The bom- bardment continued on Sunday and Monday, but ceased during the next three days, to be renewed again on Good Friday, when it reached a cli- max with the shot that struck the Church of St.~ Gervais, killing 88 worshipers. —< ARLY March, 1918, was a period of intense activity in the German Army. The very air was charged with expectancy of the big things. The war would end during the Summer in a glorious and complete victory for the German armies. Hindenburg and Ludendorff had :ssured the Reichstag of that in February, The French and British armies were low in morale. They were low in man power, no longer able to man all their bat- teries and accessory services fully. It was ab- solutely necessary for them to keep the trenches filled and a certain number of divisions of in- fantry in reserve for emergencies. During the Winter, the French had broken up nearly a hundred battalions. They had demanded that the British take over additional frontage, and with nearly 200,000 fewer men in his army than a year before, Haig had taken over 40 miles more of the line. Gen. Gough’'s 5th Army had taken that additional section, and stretched they were, to the point of ragged- ness, to cover it. All of this was known in the German armies, Nowhere was there more intense and en- thusiastic activity than down in that corner left in the line after the retirement of early 1917 on the Somme, the corner about the City of Laon, the Laon Corner. THE real surprise was coming, and the men laboring on the slopes of the little Mont de Poie, along the Rheims-Laon-La Fere- Amiens Railway, just north of the village of Crepy-en-Laonnois, were spurred to greater activity to finish all their preparations before the orders could be given for the first of a series of war-ending offensives. The German Army was going to give the world its biggest surprise, in the shelling of the City of Paris from this point. This was made possible by the combined efforts of Dr. von Eberhardt and Director Rausenberger, who, after months of weary ef- fort, had finally evolved and perfected a gun that would shoot 75 miles. Ludendorff was enthusiastic about the plan, had, in fact, or- dered the range increased from 60 to 75 miles after the Somme retreat had been decided upon late in 1916. In January, 1918, after a year’s continuous experiments at Meppen, a gun, and what was even more difficult to produce, a projectile, were made which would fire the requisite 75 miles. N There actually was no choice of positions. ‘The eastern slope of Mont de Joie, in the St. Gobain Wood, was the only possible place. This was dangerously close to the lines and easily ‘within the range of French railway guns that could be emplaced to the south, on the Sois- sons-Rheims Railway line, or to the west, on the Noyon-Chauny line, or the Chauny-Anizy- Soissons line passing through the Basse Forest de Coucy, which would afford fine concealment for such guns. Cannon of such value as these new long-range rifles should never be placed within so short a distance as seven miles of the lines as they would be here, but the com- bination of circumstances demanded the risk. Three separate positions were prepared and numbered 1, 2 and 3. Installation begun in September, 1917, was in the rather sparse and young growth wood known Ilocally as “la Sapiniers.” The installation track branched from the main Laon-La Fere line, at the Crepy station, crossed the Crepy-Couvron road; and led along the northern edge of the wood or southern edge of a partial clearing along the main railway line. Here a branch was led off to the northwest into the clearing. This was to mislead air observers. The ties for this were laid on top of the soft ground. The main branch passed on through to a point where the wood was dense and the trees highest. The other two positions were nearby, had branch lines built to service them, and were carefully camouflaged. The concrete work was particularly arduous to construct. All this work, which represented no small achievement of laboring, had been under way all Winter, and by March was completed, or nearly so. Even before the beginning of March the work of installing the gun carriages, am- munition and the guns themselves was busily under way. Men arrived daily, highly skilled men from Krupp's, battery artificers and navy personnel, to operate the guns. All of the work had been under the supervision of the navy. THE final item for assembly was the gun, the great achievement. No such gun had ever been seen before. It had been made from one of the navy’s newest 15-inch .45-caliber rifles, but now it was almost double the original gun in length. It had been tubed down to 8.26 inches. and the extension of the tube beyond the 15-inch gun made the new gun a strange looking device. This, transported on its spe-~ cial car, was run up to the emplacement, care- fully raised by crane, slipped through the cradle and its great breech lug bolted to the recoil and recuperator pistons. Work was finished at emplacement No. 1 early in March, and grand headquarters was so THE SUNDAY STAR, WASHINGTON, D. C, APRIL 20, 1930. Hindenburg and Ludendorff Convinced That Long-Distance Gun Would Play Definite Part in a Great Victory—Behind the German Lines. Receiving orders to fire the first shot on Paris. notified. The erection of the carriages at Nos. 2 and 3 was still in progress. Smoke pots were placed all about in the Laon Corner so that the emplacements might be effectively obscured no matter what the direction of the wind. ‘Telephone lines were run from battery head- quarters to a number of heavy field batteries emplaced in this region. Battery headquarters was connected by telephone with each of the Paris guns. As soon as the work of installation at em- placement No. 1 was finished, early in March, the gun crews were trained. On the 20th news of the long-expected general advance order passed like a flash through all the armies, and just before 4 o'clock the next morning, the usual first day of Spring, the German artillery all along the front of Gens. Below, Marwitz and Hutier, from the Laon Corner north past Arras, began a five-hour preparation for the first colossal offensive. As if to satisfy the impatience of the Paris gun crews, who could not see why they should not have been per- mitted to join this overture of artillery, the orders came from grand headquarters during the day to begin firing on the 23d. But those final calculations! This gun was to be operated at one elevation only, 50 de- grees. And here lay an interesting story in itself, It was just on this point that Prof. von Eber- hardt spent so much time, made such laborious calculations and presented his results to his chief, Dr. Rausenberger, early in 1916. He concluded that if one were to shoot a pro- jectile of sufficient weight through the low dense layers of air at a high initial elevation and it were possible to give the projectile an initial velocity of about a mile per second, it would very quickly, 12 miles up, come into air so rare as to offer a negligible resistance and the projectile would then have approximately the desired elevati.n of 45 degrees that Galileo had proved correcf for the maximum range in a vacuum. The projectile would go on up, grad- ually turning over from the pull of gravity, and descend finally into denser and denser air to the earth, having traveled more than three- fourths of its horizontal distanec or range in a virtual vacuum. He thought this should give an unusual range, provided the initial velocity of ahout a mile per second were possible. This had been found possible, and the elevation of the gun to give the greatest range was 50 de- ‘grees. The first item in the calculations, the range, was fixed. But even here there was something unique in artillery operations. For all normal field artillery firing the earth’s surface is a plane. But not for these guns. So great were their range, and for the range in question— that is, to Paris—that the distance from the gun to the center of Paris, a straight line be- neath the surface of the earth, of course, was nearly a half mile shorter than the map dis- tance, which is the distance on the surface of the earth. The earth, a sphere, had to be re- garded as what it is, and the straight-line dis- tance beneath the surface between two points on its surface had to be computed. This was the distance with which the gun and its pro- jectile would be concerned. And then the density of the air, that is, the reading of the barometer, and the temperature, the direction and velocity of the wind, the temperature of the powder, which was stored underground, where the most uniform temperature would prevail. THE final correction was more weird than that of the range; that is, for the compass direction. So great was the range that a cor- rection had to be made for the rotation of the earth, and this varied with the compass direction in which the gun would be fired. If, for example, it were desired to fire on a target 75 miles due south it would be necessary to air or “lay” the gun on a point east of the target. At the instant the projectile was fired it would be rotating about the axis of the earth as the speed of the gun. Seventy-five miles south, the distance around the earth in a plane perpendicular to its axis was greater; a point there traveled more miles per second, and, as everywhere on the earth, from west to east. When the projective had traveled south the distance of 75 miles, the point due south of the gun had moved on east. So to strike a point due south of the gun it was necessary to compznsate for the differences in speed of rotation of points north and south about the earth’s axis by aiming the gun east of the target. If one were to fire north, it would be necessary to air west or north, for in this case the gun would be traveling faster than the target. Every one connected with the Paris gun headquarters and No. 1 gun was astir even earlier than usual on Saturday morning. Breakfast for all was quickly disposed of. It was rapidly approaching 7 o’clock. After smoke pots in the northern corner were ordered lighted the order for loading was given and all sprang to with a will. The projectile was hauled over on the ammunition track, hoisted to the loading platférm and its.tray locked to the massive gun breech. The crew that had done this in practice so often fitted the rammer carefully to the base, slid the projectile forward to the end of the powder chamber, carefully turned it to fit into the grooves in the gun and then with a mighty heave rammed it home. The powder charges were already coming up to the loading plat- form; the first was slid into the powder cham- ber, then the second. Each was pushed forward into place with the rammer. Then two tiny pressure gauges were fitted into special sockets in the wall of the chamber and the brass-cased ° base charge was put in. The gunnery officer, with his sergeant, inspected every move criti- cally, the order to close ths breech was given and, with the turning of the crank, the huge block of steel moved across, sealing in the projectile and powder. The block was locked in place and the crew scrambled down from the platform. The sergeant inspected and set the firing mechanism and signaled “All's ready” to his officer. At once the switch was closed and, with the hum of the elevating motor, the great gun began to rise to its firing position. The gun was up; every one was out of the way who had no special function. The eleva- tion was carefully set, checked by a special quadrant and by a second gunner. All was ready. The gunnery officer had all adjacent batteries on the phone and when he received the final signal that the elevation had been checked he called to all to stand by for the order. At exactly 7:17 he gave the order on the phone. Instantly heavy guns, north, south and west, fired practically in unison to confuse enemy sound-ranging units. A second later the order was given to the Paris gun sergeant. With a terrific, crashing roar the great gun belched forth a huge cloud of orange-red smoke and incandescent gas. The projectile had gone. WI’I’HIN an hour the service of the great ’ gun was becoming a matter of routine to most of its crew. Not so, however, to the ballistic officers. Calculations, without end-— each time the examination of the pressure gauges, measurement of the state of wear of the gun, checking of the powder temperature, barometer, wind. A different weight of powder charge for each separate shot. The seventh shot at 9:01, with an appreciable overcharge, showed a high pressure. The projectile prob- ably fell 4 miles beyond the target, outside of the city walls. Nothing could be taken for granted with this gun. During lunch time word was received that the Kaiser would arrive about 1 p.m. The resumption of firing was therefore delayed and everything about the gun was put in perfect order. He arrived with others from headquarters before 1 p.m. and examined the whole installation with keen in- terest and satisfaction and remained for the first few rounds, beginnings at 12:57. Not many gun crews had had the honor of serving their pieces under the eye of the Kaiser—a long-remembered priyilege for this crew. He departed after several rounds had been fired to inspect the other emplacements. While at lunch the next day, when gun No. 3 was in action, alternating with No. 1, the admiral in charge of the gun was called to the phone to talk with headquarters. Every one was expectant; it must be news. “The French papers report a hecavy bombardment of Paris on Saturday by some German long- range guns. No such range as these guns seem to have has ever been known. The life of the French capital is completely demoralized. The battery is instructed to continue the bombard- ment.” ‘The admiral's face reflected the news as he listened to the report. The crew were hilarious when he told them the details; they must drink to such success. Wine and glasses were pro- duced and the toast drunk, “Hooch!” Hardly had the glasses been filled a second time, how- ever, when the crash of something which had exploded in the meadow below set the shelter's windows rattling. How could it be? But there was no mistaking it—a projectile of the heaviest caliber, 12 inches or longer. It could only have come from a French railway gun, and it struck midway between guns 1 and 3. This was to be real war, then, for the Paris gun batteries. The opponent had struck back, and accurately, within 30 hours of the first shot. But how could they have learned of the locations? Another heavy shell crashed farther over in the clearimg. This was no joking matter. Twelve to fifteen inch shells at five-minute intervals, and as close as those two, were not to be taken lightly. The admiral called a con- ference to decide what to do. It was decided to cease the bombardment for a few hours and to observe carefully where the shells fell Perhaps it was only guesswork on the part of the French. Distinctly lucky for the French, but most unlucky for the gun crew. Shortly after 3 o'clock a heavy shell struck a tree near Number 1. It burst immediately and a hail of fragments flew in every direction. The burst was close enough that dozens of the frage ments caught members of the crew and six were seriously wounded, among them the gun- nery officer. Tragedy at the gun end of the bombardment had come much sooner than any one had anticipated. At 7:30 the following morning, Monday, after their own shot, the crew of Number 1 heard the expected discharge at Number 3. At 7:37 they got off their own shot; the lowest pressure yet, 6 miles short; it may have fallen as far out as the suburb town of Drancy. Continued on Sevemth Page