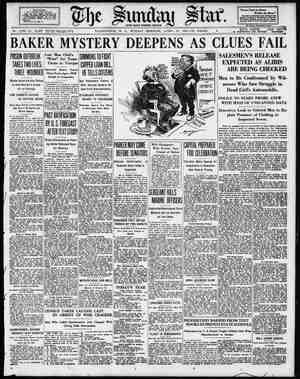

Evening Star Newspaper, April 20, 1930, Page 86

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

A Story With an Easter Angle. It Will Touch the Heart of You. S Slade, a small, wiry man with alert eyes and a keen, pointed face, rose to his feet Morton looked at him dully. He was tired. Conscious of an overwhelming weariness, stupefy- ing him, weighing him down, as if heavy, im- placable hands were pressing on his shoulders. “Think it over, Jim,” Slade was saying in his quick, staccato way. “You're just the man to put that sawmill on its feet. It won’t be easy, of course. But there’s a good salary in it for you and a third of the profits after you've pulled it out of the red. And as for that money you owe, don't give it another thought. I'll lend it to you at & per cent interest and you can pay back the principal $1,000 a year.” “Thanks, Tom; thanks a lot. I'll let you know in the morning,” Morton said, but there was no life in his voice, and for a long while after the door had closed on Slade's quick, energetic figure he sat at his desk staring ahead of him with tired, defeated eyes. He should have been grateful to Slade and in a way, an inert, exhausted way, he was. Five years ago when he was 34 and still hug- ging his illusions, he would have jumped at this solution of his difficulties. But five years ago he had not been the bankrupt he was today. And it wasn't only his debts nor the fact that his business was staggering on weak, tot- tering legs that had stripped him. The cause of his apathy, his disinterest, went deeper than that. He had expected things of life, and life had failed him Or, perhaps, he had failed it. It didn’t matter which way you put it, the net result was the same. And now it was nearly Easter, the time for reawakening, but there was no miracle in his heart. NONE of the triumphs he had envisioned for himself had come true. None of the am- bitions which had seemed so easily attainable in his young manhood had ever been achieved. JHe had been confident, swagger, thinking the world his foot ball. Fresh from college, where he had been somewhat of a campus god because of the success with which he had cap- tained the teams, he had thought in terms of victory. He was laughing, debonair, a comer; believ- ing in himself so gorgeously that Mary—he winced when he thought of Mary—had be- lieved in him, too. With what assurance he had stormed her! With what exultation he had won her, snatch- ing her away from Peter Downes, the only son and heir of the oil magnate, to whom she was all but engaged. “You won't regret it, darling. Some day we'll have a house that will make that pink stucco place of theirs look like a strawberry sundae,” he said, as he slipped his tiny diamond on her finger. She had put her arms about his neck, he remembered, and her eyes had been glowing and proud when he swept her to him in the flower-spiced sweetness of the Summer dusk. But the some day of which he had bragged had never come. He had failed Mary. The tiny diamond, which he had promised to replace with a larger, more brilliant stone, still winked at him tauntingly from her finger. The small, five-room cottage in a drab, unfashionable part of town, into which they had moved when Helen, their daughter, was born, still roofed them—Ileakily, as Mary often said—and what is more, it was mortgaged and much in need of paint. And though they had a car, it was :mot the costly low-hung, rakish affair he had once pictured himself giving Mary on a birth- day or a Christmas, but a cheap, square-built, four-cylinder make. Into Mary's eyes, once so proud and glow- ing with their faith in him, there had come a different expression. Gradually he had seen the faith dimmed by doubt, and the doubt harden to a look of permanent disillusion. Spring came and with it Easter, and every year the dream had grown fainter. Poor Mary! For the bright some day which he had promised her, she hoped no longer. For years she had scrimped and saved and cut corners, buying her Winter felts when it was Spring, and her Spring hats in the Fall when straws were bargains. “Don’t worry, darling. It isn't your fault if things don't break for you. One of these days you're bound to go over,” ‘she used to hearten him, but that was before she had come to have the patient, dogged, lack-luster look of women whose men have failed. HOW completely she had accepted his de- : feat he had realized the past Winter when she had taken a job with the Young Women's Club. “We need money so terribly, Jim. The hours are short and the salary good. Junior's 5 now and though I've always said I'd never leave him to the care of a nurse, I've had to come to it. You see, yourself, how the bills are piling up on us, and as for my clothes, they're in rags. If I take this job I can help you with the expenses and afford to have a servant—a dependable woman to stay with June while I'm downtown.” “Oh, of course, if you want to,” he had said, hating the idea, yet feeling that he, who had given her nothing but thin bread, had not earned the right to object. And shortly after that Helen, who was slim and choppery-haired with a vivid, life-loving mouth and dark, restive eyes, had announced her independence. At high school she had taken a business course and there was a job THE! SONDAYIATAR, WASHINGTON, D. C, 'APRIL 20, 1930. THE MIRACLE By Margery Land May. “But you're going there, Daddy. Mammy says so, "cause you mowed the grass on Sunday. . . . And, don’t you see, now that I've took big sister’s purse I can go, too.” she could get, “a pegpfectly spiffy job,” as at- tendant in a doctor’s office. “But Helen,” he protested feebly, “you’re so young!” At this objection, Mary’s mouth had set in a firm, determined line. “It’s a nice place, Jim. I've already talked with Dr. Johns about it. And as long as Helen has to work she may as well start early.” As long as Helen has to work! He had shuddered when she said the words and, sit- ting at his desk in his quiet, shabby office, he shuddered now. His women—wanting things! His women—setting out to get for themselves the cake, the frosting that he, their man, was incompetent to provide. And how they had expanded under their freedom! How it had thrilled them to have their own money; to be able to buy their hats at the right instead of the wrong season! Of a sudden, almost overnight it seemed to him, they blossomed out. Like April flowers, breaking with quick magic through the brown crust of the earth, he saw them drift before him in sheer and flimsy things, whose life was as brief and as bright as the hyacinths of Spring. Hidden behind the newspaper, apparently oblivious, but with burning ears, Morton would listen to their careless, bubbling chatter. He was shut out from them. Removed. The more established they became in their independence the further he was pushed away. Gradually, though they did not realize it, he was becom- ing gray and hazy, like a shadow to them. To the boy alone, a red-cheeked, brown-legged rascal, was he still an identity. But the boy was too young to know that, in his primary obligation as father, his daddy had failed. A faint smile of tenderness broke through the tired gray of Morton's face as he thought of the boy—June Bug, he called him. Then, as suddenly, he frowned. He didn’'t like, had never liked the idea of leaving him to the care of that white-toothed, ebony-skinned, old mammy who was filling his mind with all sorts of darky superstitions. Why, only yesterday when he went in to kiss the kid good night he had been excited and pink-cheeked over mammy’s notions of hell. Looking at him with wide, frightened eyes, he had said: “Daddy, you mow the grass on Sunday. And you shouldn’t. Mammy says folks who do things like that burn up in the bad place,” June had said. Fine stuff for the impressionable mind of a child, but what could he do about it? The old Negro woman was dependable and loving, at any rate, and as long as Mary and Helen worked downtown, some one had to be at home to look after him. BU‘I‘ it was wrong. All of it. The whole" scheme of things was awry. He had made it so. Failure had become a habit with him. Once he, like the rest of humanity, had boosted himself with the universal catchword, “Some- thing’s bound to turn up.” But no longer. Men were like children. At first they believed in luck, in gold at the end of the rainbow. Whey jest eouldn’t take it in that life wasn't gring to be glotious—some day. But later when dreams turned to ashes and hopes to gray dust they had to face it. The happy-ever-after illusion of their youth became an illusion, not a golden reality beckoning from the next corner. He laughed grimly. Five years ago he would have been tricked into expe¢tancy by the opportunity which Slade’s offer held out. But now he saw it for what it was. A chance to sweat, to fight, to pull the breathless carcass of a dead business back on its feet. Good enough in its way, he supposed. But he was too spent, too utterly sapped, to want to fight. Perhaps if some miracle could infuse his heart with courage and his veins with the energy of fresh, leaping blood—this was the resurrection season, Easter, time for mircles—but there weren't any miracles. He knew that, admit- ting the grim fact of a miracleless world at last. He was tired. What he needed was sleep—a long, unbroken rest in the bosom of the earth. And there was a way—his breath caught, his eyes glistened with the promise of it—a way to get it. Driving home in the shabby, square-built, four-cylinder make, he passed the pink stucco palazzo which belonged to Peter Downes and Driving home in the shabby four-cylin- der make he saw a gleaming, long- bodied car purr up the slope to the entrance of the pink stucco palace which belonged to Peter Downes and the girl he had married when Mary had made her foolish choice. the girl he had married when Mary made her foolish choice between concrete reality and the will-o’-wisp of faith. As he drove by he saw a gleaming, long-bodied town car purr up the slope to the entrance. On the front seat were a liveried chauffeur and a magnificent, henna- colored chow. On the back seat sat a woman, expensive, elegant, with a delicate, unlined face, framed in fur. She had a precious, treasured look—that woman. For her Downes had done all the things—to her given all the things that Morton had promised Mary. White-gloved and removed from common contacts, she leaned against the upholstery, not moving until the A Man Decides He Is a Failure in Life; Then Comes a Child’s Voice. butler hurried down the steps to open the door of the car. “Mary could have had all that,” he thought dully, and wondered why, when he would soon be leaving it forever, he was returning to the home where his presence, his influence, had become a mere shadow on the wall. And then the question answered itself. He wanted to see the boy, of course—the peache cheeked, sunny-haired little ragamuffin who always ran to meet him at the gate. But this evening as he got out of the car there was no shriek of rapture, no blue= rompered figure to catapult itself into his arms. At this absence Morton’s heart gave a sickening lurch and the steps with which he approached his house quickened to a run. A dreadful anxiety was gripping him as he flung the front door open and strode into the hall. With reassuring calmness Mary turned from the flowers she was arranging to greet him with: “Hello, dear! Have a good day?” He looked quickly, searchingly this way and that. : “Where's June Bug?” he demanded. Mary’s face clouded. “He's been very naughty, Jim. I sent him to bed. He took Helen’s purse. Denied having seen it when we questioned him, and then when we found it hidden in his toy box he wouldn’t tell us why he had taken it. I was horrified and sent him to bed at once. I wish you'd go talk to him,” she said. Though Morton’s first emotion was one of relief, it was instantly succeeded by a paralyzing shock of another kind. “That’s what comes of leaving him to the care of a woman,” he thought as he opened the door of the nursery and saw June’s flushed, tear-stained face against the pillows. “Daddy! Daddy!” At sight of him Junior scrambled to his knees and in another moment Morton was sitting on the bed with the warm, squirming little body in his arms. ORTON pressed his cheek against the salt of Junior’s tears. “Mother says you've been a naugh > told him. - “I did take it, daddy. I did. I did,” he cried in a childish treble that caught on a sob. “But why, son? Why did my June Bug do such a wrong thing as that?” Morton asked, perplexed and troubled. For a moment there was silence, Then, hesie tantly, with one round fist pressed into the corner of his eye, Junior answered: *“’Cause—'cause I want to go to the bad place.” . “The bad place! Why, June!” Morton was dumbfounded. At the gravity in his father’s voice the boy’s face puckered with fresh tears. “But you're going there, daddy. Mammy 8ays so, ‘cause you mowed the grass on Sunday. And, don’t you see, now that Yve took big sister’s purse, I can go, t00,” he explained. Morton’s heart stood still. He could not bee lieve his ears. And yet he wanted to believe them—knew that to be able to believe them was life itself to him. In a minute, in a second, he would chase the goblins from this baby’s mind, but now—now—-" In a deep, shaken note he asked him: “But, son, wouldn't you be afraid?” The small, sturdy body snuggled down closer in his clasp. “Oh, yes, daddy, I'm ’fraid! I'm terrible "fraid. Witches is there, mammy says. And a burning lake and a red devil with a tail and a long pitchfork. But if you're going there I want to go, t0o,” he said. At his words Morton’s eyes stung and there was something hard and dry sticking in his throat. Fool that he had been! Cowardl Here was the miracle he had doubted, the tonic to put courage in his heart and into his veins the fresh energy of swift blood. It was Easter, A shining miracle had been reborn again! June loved him! Enough to brave the utmost terror of his child’s imagination. And he? He could start again and live again for June. That sawmill! It would be a cinch to put that sawmill on its feet. Child’s play! ::le could do it! He could do anything—for une. Suddenly he felt young again, strong again, triumphant! He laughed. And his step was light, buoyant as a boy’s, when he went to phone his answer to Slade. (Copyright, 1930.) Virginia’s Soapstone. NEVER any one expresses a word of appreciation for soapstone Virginia can rise and take a bow, for all the soapstone pro- duced in this country comes from the neighe boring State. Any one questioning the appreciation of soap- stone may find reason for reflection in the list of uses of the stone, which include laundry tubs, trays, sinks, laboratory table tops, bus-bar come partments, store fronts, electric insulating mae terial, acid tanks, stair treads, furnace blocks, fuse guards, tiles, aquariums, switchboards, panel boards, insulators, wainscoting, fireless cooker stones, hearth linings and furnace lin- ings. If this list of uses fails to bring the thanks of the reader, he might recall the steaming hot pancakes that have slid toothsomely off the soapstone griddle onto his plate at breakfast time.