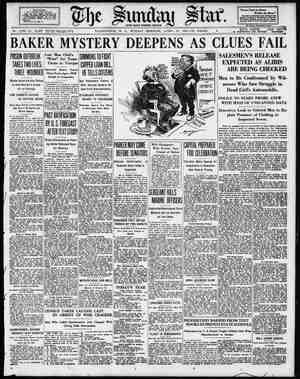

Evening Star Newspaper, April 20, 1930, Page 82

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

| s . o THE SUNDAY STAR, WASHINGTON, D. C, APRIL 20, 1930. Faster Customs and Legends Around the W orld The Feast Day Was Celebrated by Pagan Rites in Honor of Sbring Long Before .Coming of Savior—Symbolizing New Life, Resurrection, the End of Winter, the Dawn of the Season of Flowers, Festivities Throughout the Ages Have Taken Many Forms in Different Lands and Countries. @ “Apis Osiris,” by Frederick Arthur Bridgman. An ancient festival given in honor of Osiris, the Egyptian god of verdure, BY MYRTA ETHEL CAWOOD. INCE the beginning of time man has celebrated the annual rebirth of na- ture, which embodies the spirit of resurrection. The pagan feast of Eostur was given in honor of Spring long before the Christ was born. Easter, as we know it today, is the commemoration of an event and not an anniversary, for no one knows the exact date that Christ rose from the dead. Because of the poetic resemblance of the resur- rection of Jesus to the rebirth of nature the early Christians grafted the festival of Eostur onto the pagan celebrations of Spring. Ever since the world began all nations have expressed their inherent thankfulness for Springtime by elaborate national feasts. Each country has it own name and legend for such celebrations. To the Japanese it is the merry festival of the cherry blossoms, while the Chi- nese burn the Spring ox and scatter its ashes over the land to insure good crops. When the waters of the Nile rise in the Spring and threaten to ruin the new crops the angry river is appeased with a young bride In ancient times a beautiful virgin was clothed in rare silk and glittering jewels and cast into the foaming waters—wedded to the Nile. In re- cent years the living sacrifice has been spared and King River is offered a dummy bride in- stead. In some countries near the Equator the Southern Cross is worshiped because it is be- lieved that the crops come from the south. But the Brahmins dedicate the Tamil new year, or the Spring, to the spirits of their departed ancestors. They think that people, like nature, live anew in the Spring. In India, Springtime is considered the marriage season. Madana and Rati, the god and goddess of love, are wor- shiped at this time by public ceremonies and dances in which great garlands of flowers are used. SPRING is truly a season of promise, the resugrection of the sun brings new life and food after the hard, cold Winter. Nature is reborn, but what about man? For untold centuries philosophers and scholars asked the question. Finally it was answered—in the Christian religion—by the dramatic event of the resurrection of Christ. On a Sunday morn- ing He rose from the dead, and this day became Easter, the most joyous festival of the Christian calendar. It commemorates the great histori- cal fact and fundamental truth upon which the whole structure of the Christian religion rests. Although every one, pagan and Christian alike, knew, when Spring came no one could determine the date of the resurrection. For more than three centuries after Christ bitter quarrels waged as to the proper date of Easter. All factions agreed on one thing, that Christ yose on a Sunday morning—before the cock ecrew. But which Sunday? The early Christians relished controversies, They used to fight over hypothetical questiors, such as the number of angels that could pirouette simultaneously on the point of a needle. Is it any wonder, then, that they could not decide among themselves the exact date of the resurrection? Finally the matter was referred to the Coun- ¢il of Nice. That august body decreed in 324 AD. that Easter should always fall on the first Sunday after t} e full moon which comes on, or next after, t¥™ vernal equinox—which is March 21. It may come as early as March 22 or as late as April 25. Between the years 1916 and 1965, Easter occurs 40 times in April and 10 times in Mar-h. In the beginning of the gourth century ¥mperor Constantine passed & law which stated that all the movable feasts of the Christian calendar should depend upon Easter Sunday. BU’I‘ the word Easter itself is not of Christian origin. ‘The original meaning of the word is often disputed. Historians have claimed that it is derived from the name of the ancient god- dess, Ostara—or Eostre—who personified the Spring, the east, the morning and all things new. Ostara’s month was called Eostur-monath and it corresponded to our April. There are other writers who say Eostur-monath was named for the old heathen feast of Eostur—or Easter, which was so called because the Spring sun rose in the east. Still others claim that Easter is derived from the ancient word Oster, which signifies rising. Winter was & frightful ordeal to the ancients. They had never dreamed of such comforts as steam-heated houses and canned food. Is it any wonder that they celebrated the warm Spring and new food with unrestrained joy? When the first Christian missionaries went to England to introduce Christianity the pagan celebration of the Eostur festival reigned su- preme. The missionaries soon found that the festival was deeply rooted in the lives of the unbelievers. The Christians tried to abolish this heathen custom, but they could not, so they welded its spirit of joy and thankfulness onto the Christian calendar and give it the deep significance of the resurrection of Christ. This was not hard to do; the resurrection of new life in nature needed but the dramatic episode of the risen Christ to make it perfect. The French, Italian and Spanish words for Easter are derived from the Hebrew name of the Passover, which is pesach. This feast, among the Jews, commemorates the act of the angel of destruction who smote the Egyptians, but passed over the houses that were sprinkled with the blood of the “pascal lamb.” The early Christians saw an allegorical resemblance to the Jewish Passover in the resurrection of Christ, in that the lamb of God was actually sacrificed to save the people. The pagans celebrated the Spring about the first day of May and many of our present Easter customs are easily traced to this fes- tival. The Oestra celebration consisted of riot- ous games, sports, dancing and farcical enter- tainments. It was the custom to dress in new clothes and garlands of flowers. So we find that new Easter clothes and Easter parades have pagan origin and were practiced long before Christianity. The early Christians were, in fact, a doleful class of people. The pagans furnished the elements of hilarity to such Christian festivals as Easter and Christmas. “Easter fires” have their origin in paganism. It was an ancient custom to ‘build great fires on the mountain tops to celebrate the triumph of Spring over Winter. The flame had to be kindled from new fire created by friction. Often a figure representing Winter was hurled into the bonfires. The Christians tried to stop this heathen custom also, but .could not, so they gave the new flame struck from flint a Christian significance. It now stands for the reappearance of the Light of the World out of the tomb of stone. One of the most sig- nificant spectacles in the pageantry of the Easter celebration at Rome is the spectacular lighting of St. Peter’s, called the ‘“silver” and the “gold illumination.” The Sun Festival, which is still practiced by almost ail the heathen countries in the world, is a relic of prehistoric days, when the planets were worshiped. The deep-rooted beliefs of the sun worshipers are probably -responsible for the ancient superstition that the sun danced and spun around like a cart wheel three times as it rose on Easter Sunday. The pagans themselves used to dance at a festival in honor of the sun after the vernal equinox. But the early Christians thought that the sun actually spun around three times to commem- orate the third day on which Christ arose from the dead. To this day the Devonshire children get up early on Easter morning to see this remarkable feat. Elaborate devices, such as mirrors and tubs of water, are set to entrap the image of the sun. A slight movement on the surface of a pond or tub of water materially strengthens this illusion. IN East Yorkshire it is considered exceedingly unlucky for those who wear old clothes on Easter. The ‘“rooks” or “crakes” are said to spoil all clothes except new ones. Particularly must the young swains wear new clothes on Easter if they wish to be lucky in courtship and marriage during the “wooing season,” which is, of course, the Springtime. The Chinese New Year, L8 Ch'un—the begin- ning of Spring—is the greatest festival of the Chinese calendar. Morally it represents the idea of resurrection, the rebirth of the year. It is a season of great rejoicing. The Chinese have no Sundays or one-half Saturday holidays, so their feast days are needed for resting. But there is little rest. The people busy themselves by preparing many gifts for each other, such as food, tea, fruits and growing flowers—never cut blooms. The climax of the three-day fes- tival is the pageant and sacrifice of the Spring ox. At the exact hour that Spring begins the great procession stops and the ox is beaten by willox twigs decorated with ribbons of colored paper. The beating is to “rush” the season and to incite the farmer to begin work in his field. If the ox is not well beaten there will be a late Spring. After the ceremony the ox is burned and the ashes scattered over the land. The people then go home, take off their furs and flannels and don Spring clothes. In re- cent years the ox and driver are made of paper, but in the earliest days of Chinese history a real ox was slaughtered and its raw meat di- vided among the worshipers. The sacrificed ox is the identical principle of the lamb of the Israelites in ancient times. It was the invariable custom of the ancients to offer a living sacrifice to the god of Spring, In some remote sections of India the natives celebrate the Tamil, or Spring season, with great military pomp and ceremony. At the end of the three-day holiday a buffalo is slain by a man whose right to perform the ceremony is hereditary. There is great rejoicing among the men. Women are not allowed to participate in this event; they stay at home to prepare the great feast, which must be ready for the men when they return at night. In India the word “year” originally meant “the Spring,” and the season was celebrated by offering flowers and the first fruits of the year to the dead—both the human dead and the dead Winter. In some far corners of the globe the heathen still celebrates the Festival of the Dead. The Hindus believe that the pious who die in the Spring go straight to heaven, but those who, unfortunately, die at other sea- sons must remain in the nether world to be born again and return to earth to work out their true salvation. A person dying in the Spring is buried with his head to the south, where the death god Yama abides. An ancient legend says that the angel Trisanku was hurled from the heavens, but caught by Yama and suspended in the southern sky because of his goodness and valor. This is tF2 story of the agriculture and germinating new life. Courtesy of Corcoran Gallery of Art, blazing Southern Cross, which is still worship= ed by scattered tribes in the South Sea Islands because it typifies the South—the home of Spring. For unknown ages inhabitants along the Ganges River have taken their annual bath in the Spring. This yearly immersion is not so much for bodily cleanliness as to purify the soul and give it a new life—to wash away all sins. THE first temple to Ceres, the Roman goddess of grain, was built in 496 B.C. to com- memorate the deliverance from a great famine, At the ancient Festival of Ceres it was a prace tice to fasten burning brands to foxes’ tails, The foxes—or corn spirits, as they were called— were turned loose and left to burn, so that their ashes might charm the grain and pro- duce an abundant crop. During this festival grain was scattered about the earth and thrown upon people, because it represented fertility— the germ of life. Our modern custom of throw= ing rice on newly married couples can be traced to this old pagan festivity. Long before Christ the Romans burned a new-born calf and scattered the ashes over the soil to induce the earth to yield much- grain. This custom was later introduced into China, and as late as 1804 porcelain images of cows were presented to farmers in the Spring to bring a good rice crop. In North Germany, Scotland and England the shepherds to worship Pales, the shep- herd’s god, in Springtime. The sheep were first purified by brushing and washing, then sulphur was burned about them. At night the shepherds lighted great bonfires and danced among their sheep by the light of the moon and the fires. In the morning the shepherd looked to the east, toward the resurrected sunm, and washed his hands in dew. In some sec- tions of Europe the shepherds still dance at Eastertime among their sheep, which now typifies the slain Lamb of God. But holy water takes the place of the dew in the Christian ceremony. The lamb is one of the earliest symbols of the resurrection. Among the Christians of the East a young lamb is always eaten on Easter Sunday. During Passion week hundreds of Spring lambs are brought into the market places and sold for the Easter feast. This is a great time for the children of the houschold, who make friends with the lamb as soon as it is brought home. They tie ribbons around its neck, legs and tail and hang garlands of flowers about its body. Often the father finds it diffi- cult to separate the lamb from the child. But a lamb must be slaughtered for the Easter feast, so two lambs are usually bought—one for the children and one for the festival. The spared lamb becomes the children’s inseparable play= mate. At bedtime they argue with each other to decide who shall sleep with the lamb. Per- haps this old custom inspired the famous nursery rhyme, “Mary had a little lamb and everywhere that Mary went the lamb was sure to go.” In England and France it is considered a good omen to see a lamb on Easter morning when one first looks out of the bed room win- dow. If the lamb’s head is turned toward the house any wish that is made will come true. It is commonly thought that the devil can take the form of any creature in the world except the lamb and the dove. In Mechlenburg the peasants wash in Easter water, which must be rain water or dew. This act of washing is supposed to ward off sickness.