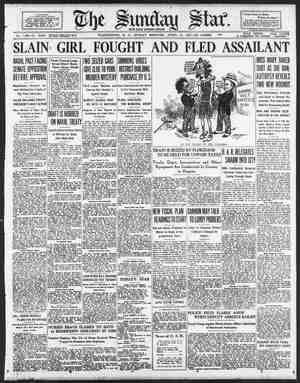

Evening Star Newspaper, April 13, 1930, Page 99

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

THE SUNDAY STAR, WASHINGTON, D. C, APRIL 13, 1930. e o e How the Holy Family Lived in Egypt American Scientists, Studying Relics of Ancient Egyptian Small Tozwns, Find Houschold Imple- ments Like Those That May Have Been Used by Joseph, Mary and the Christ Child, While They Hid From Herod. BY FRANK THONE. NTO Egypt fled Joseph and Mary and the Child, with the mad blood lust of Herod at their heels. Once across the border they could rest, and slip into the safe obscurity of a small town, until such time as it would be possible to return to their own land. They would rent a small house, and Joseph would hunt up jobs of wood-working such as carpen- Yers can always find, and life in exile would not be so different, after all, from life at home. They would scarcely even be noticed as foreigners. There were no end of Jews in lower Egypt, and the arrival of another family trom the north was merely something for a few bored immigration officials at the border to note down in crabbed Greek on a long-snce- perished papyrus roll, before they turned back to their office gossip, forgetting the newcomers before the dust of their plodding donkey had settled in the road. 3 Nobody knows where the Holy Family went in Egypt, though it is unlikely that they troubled to journey far beyond the border. Nobody knows how long they stayed there. One common tradition says seven years; but since they returned to Nazareth soon after the death of Herod, 't is unlikely that the Egyptian sojourn lasted that long. As nearly ¢s can be made out now, Herod died a few months after the birth of Jesus; it may be that the massacre of the innocents was an act of madness fore- boding his end. But when all is said, this episode in the life of Christ is and will remain obscure. Half of a terse Chapter in the Gospel according to St. Matthew tells all we know about it. ECENT researches by American archeolo- gists in the ruins of an old Egyptian town have thrown a flood of new light on how the common people lived in the villages and small cities of Egypt during the time the Holy Family sought refuge there. Out of the dust of centuries they have dug the remains of the little houses of sun-baked brick where the folk lived there unobtrusive lives. “"ney have found door and window frames o! wood, wooden stools and reading desks, wooden rakes and pitchforks—even wooden door locks with wooden keys! There evidently was no lack of work for Joseph. They have found glass dishes and woven baskets, such as Mary must have used in her housekeeping. They have even found quaint little wooden toys, oddlv like modern playthings sometimes, such as Joseph might have made in his odd mo- ments for the amusement of the little Jesus. This is a new kind of Egyption archeology The scientists of the spade have hitherto con- cerned themselves mostly with relics of the great, tombs of nobles, pyramids of pharaohs, encrmous temples of the gods, But history does mot consist wholly of the record of the wars and wranglings of the great. There are also the laborious poor, on whose mu’ti1ie of bowed backs thorns have always beenn “orne. What of the common people of Eg Ta” new view of history led the Near East Research committee of the University of Michigan to seek for a site in Egypt where the common people had lived their common lives— a mummified Main street. SUCH a place they found finally, not in Egypt itself, but in the Faiyum oasis. This valley of gr-n, which lies beyond 1 naked ridge of stone hil's in a basin cut down into the Libyan cesert, is a sort of annex or suburb of Egypt proper. This region the Ptolemies brought under cultivation ‘n one of the greatest reclamation projects of ancient times. This Ptolemaic boom in real estate started more than two and a half centuries before the Christian era, and ended in the decline of the settlements when irrigation went to wrack and ruin during the civil wars that attended Sir John E. Millais’ famous painting of the boy Jesus % % 3 in the home of His parents. Science now doubts the accuracy of the : details of this picture. The basket being woven at the left is correct, but the vise on the carpenter’s bench, and-the saw on the wall belund, may not have been invented. Along Karanis' “Main Stem.” Crumbling ruins of stone temples mark the center of old Egyptian towns. just as the city hall or public square dpes today. the downfall of the dynasty. Twice in later days these towns experienced a similar fate, their complete desertion falling in the fifth Christian century. Thus the task of archeologists who would study the small-town life of Egypt at a given period is simplified if they select the ruins of one of these towns in the Faiyum. It had a definite beginning and a definite end, and the situation is not complicated by finding manifold layer beneath layer of antiquity. as would be the case in almost any village in the Nile Valley proper, where the same sites have been inhabited from Neolithic times down to the present day. The town of Karanis, which the University of Michigan expedition selected as a specimen city for its investigation, had a population of perhaps 5,000 in its best days. Dr. A. E. R. Boak, who initiated the work which is still being carried on, says he expects after further study to know exactly how many taxable peo- ple lived there during at least one period in the town’s history, and (ven to know their names. Among the papyri recovered from the ruins are numbers of tax lists. Egvptian officialdom has held the all-time world championship in ingenuity and thorough- 1ess of taxation schemes, and it is a pretty safe bet that no person or piece of property in Karanis ever escaped the assessors. After Dr. Boak has had time enough to pore over sheet after sheet of cracked papyrus, he will know more about the Karanians of 2,000 years ago than most American towns can learn of their own history of 50 years back. For the papyrus rolls, preserved by the dry climate, are in ex- cellent condition, and may be read by scientists more @ccurately than yellowed records faded in northern climates, But without waiting for the slow deciphering - . of the tax rolls and other written reeords it is - still posSible to learn a good deal about these small-town folks of long ago. The broken walls of the buildings themselves, buried in drifted sand, tell a story that he who digs may read. KARANIS has known three different periods, and there are three levels of foundations separated by layers of sand. But the three towns that grew successively on the same site were very much alike, and fundamentally not unlike towns of similar size in medieval Europe or the Maya Empire or modern America. There was a center around which the life of the place circulated, and this was of stone. There were the houses and shops in which the people lived and traded, and these were of less pretentious construction. Here, as elsewhere in Egypt, house construction was of sun-baked brick, much like what we call adobe in our own Southwest. The walls were built farly thick, and the houses were small and set closely together. The principal building, occupying the place in the Karanian scheme of things that the county court house holds in our modern main street towns, was the temple. The ruins of its stone walls and a stone altar that attests its character have been brought to the light of - day. The presence of a temple as the most pretentious edifice does not argue that the people of Karanis were more pious than they . were patriotic. Religion and citizenship were the same things, both in Egypt and in Rome; Pharaoh or Caesar was not only a civil ruler but a high priest and a god in his own right. BUTltlslnthemomsotthcho\m'hm the people once lived, yoofless mow and with broken walls, that the most human and appealing chapters of the story of humble life in ancient Egypt may be read. stuff would have in a moister climate, and at last the roofs and walls fell in and the drifting . sands completed the burial. found ingeniously whittled out of timber. Perhaps the most remarkable and complicated mechanisms are the wooden door locks, opened with wooden keys. These are, to be sure, much larger affairs than the compact iron and brass devices that guard our own front doors. The . wooden blocks that cover the sliding wooden bolts are half the size of a common brick, and . the keys are six or eight inches long. But apparently they served their purpose. More orthodox in appearance are wooden hayforks, carding combs, spindles, door frames. A curious piece of furniture is & wooden read- ing desk. This is in the shape of a wide but shallow trough. The two boards that form its _ top meet in the middle to form a wide “V,” which prevented the rolls of papyrus that were the commonest books of that day from falling off. The desk is only about 4 inches high, - and must have been used by a student cross- legged on the ground, a position still much used among Orientals. ‘-~ JMIOST of the wooden articles are made of ordinary varieties of timber, but the car- penters showed the love they have always had for good tools. Numbers of mallets and wedges have been found that are made of mahogany, But wooden things are not the most perish- - able objects that have been held imperishable . by the kindly sands of oblivion. Woven and plaited fabrics of many kinds that helped folks to make a living long ago are turned up here in quantities, each new object an added para- graph in the mute inglorious history of a for- gotten common people. There is a camel har- ness, woven of cords, a fishnet. It is in household gear, however, that the ruins are richest. The people of Karanis were not rich, and they lived simply, but they had their own standards of comfort. Metal pots and pans for the housewife's kitchen work were of course unknown, but earthenware pots she had in abundance and in all conceivable sizes ard shapes. J/Great pottery jars for the household supply of water stood by the door, on stone stands. . Pttery lamps hung from the ceiling beams or ~ stood on wall brackets. The lamp makers seem to have been an artistically inclined group of craftsmen, for not less than 150 designs have been found among the lamps of Karanis. ANYBODY who thinks that glassware for table use is a modern invention will have his eyes opened if he walks through the rooms of the museum at Ann Arbor. These Karanian women liked nice things, too, and they could set well shaped glass bowls, goblets and bottles on the table when there was company for din- ner. Most of it is delicately tinted glass, too. The blues and greens are especially attractive. And when a hostess of Karanis was getting ready for her guests she had appropriate toilet aids. Only fragments of these two-millenniume old toilet sets can be assembled, but even the pieces are eloquent. There are several combs made of hard wood, accurately cut in a pattern - still followed by the more modern hard rubber - and pyralin products. There are pots for kohl, that eye-darkening cosmetic so universally used - throughout the countries of the Bast, with sticks and-a spoon for s application. Lot AN CC AR L