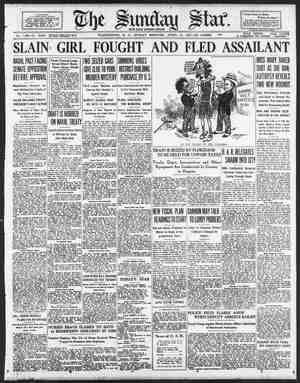

Evening Star Newspaper, April 13, 1930, Page 33

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

Special Articles Part 2—-8 Pages WORLD SOON MAY KNOW . REAL STORY OF WAR Pershing, Clemenceau, Foch and Others May Yet Reveal Battles Waged by Allied Commanders. “our BY THOMAS M. JOHNSON, Author of “Without Censor” and Secret War.” RE we going to know at last the full inside story of the greatest battle of world history, which was also the greatest battle Americans ever fought? More, are we going to hear all about the battle within that battle, whose issue determined the issue of the World War—the unknown struggle on the heights of Olympus, cloud-hidden, of the gods who in 1918 controlled world destiny: Foch, Pershing, Haig, Lloyd George and, perhaps, greatest of all, Clemenceau? Remember how—aided by propaganda =—we visioned them then, sublimely perfect. supermen, supperpatriots, nobly, even blandly, superior to common pas- sions? Can it be true that, after all, there were times when they resembled more an afternoon bridge club squabbling over the score and the prizes? Per- haps—or so it seems now that the dead hand of one of them has rent the veil of the temple. Other Views Coming. For Clerizenceau has written a book, wherein he has told things hitherto unknown of happenings on Olympus. And is it mere coincidence that Per- shing has resumed vigorously writing his side of the same great event? And Foch's own book is soon to appear, fol- lowed by a Foch biography written with help from the marshal's widow and his devoted Weygand, by the brilliant Eng- lish writer, Capt. Liddell Hart. ~The lowdown on the Olympians! ‘What did they really do and say and think up there on the heights when victory and defeat trembled in the scales? Did human passions rise and fall, too, as dominant personalities un- der great stress, strove for victory over the enemy, and, sometimes, over one another? How they strove appears in the dra- matic, ?wlgnam circumstances of the death of Clemenceau, “Tiger of France,” who but recently died fighting, after all. He had tried to rest from his bat- les, but fate, and Foch, and his own flery spirit would not let him. He seized again the pen that was his sword and perished by it. Astonishingly, the battle that this celebrated French- man died fighting was, in part, an American battle. Inside Facts Are Due. Nearly 90 years old, the Tiger stalked the kill again, snarling eagerly to tell the whole world his part in that battle, the Meuse-Argonne, and what has been called his intrigue to have Gen. Pershing removed as commander in chief of the American Expeditionary Forces. He had been stung by the action of his celebrated compatriot, Marshal Foch, former commander in chief of all the allied armies, in telling his side of the battle within a battle—a side that dif- fered from that of the Tiger. France's great soldier had revealed how France’s World War premier had wanted to appeal to President Wilson to send some one less independent, less stubborn, to command the American Army—some one who would yield more to allied ideas. The marshal told how he had opposed Clemenceau, favored Pershing. Then he said, after he, Foch, had won the war, Clemenceau had lost the peace. That caused a furore in France, lively interest here, This remarkable quarrel that the two foremost Frenchmen carried to their graves, has not yet subsided and cannot until their books appear, to be scanned by an eagerly curious world. A pre- view can be had in part, by narrating chronologically certain events whereof the average reader knows nothing, al- though they determined the course of 1918 when Foch and Clemenceau snatched triumph from disaster, but in 1919, did not treat those two quite the same. Different Types of Men. Not strange, for how different they were! Clemenceau—hardheaded, cyni- cal, agnostic; Foch—inspirational, mys- tic, religious. Love of France held them together in war, separated them in peace. When peace came, love of France pulled them in different paths. ‘They could not agree what was best for La Patrie. ‘That was not until after the darkest, tensest hours of the war's crisis. They worked together then, although Foch had become allied commander-in-chief over the dead body of Clemenceau's ambition—as few Americans realize. ‘The Tiger wanted to be commander-in- chief himself, although he was not a soldier. But British and Americans wanted Foch, so the Tiger yielded, but with il grace. Once he told Field Mar- shal Sir Henry Wilson that it_needed Just two men to win the war; a French- man and an Englishman, If and 8ir Henry. That was when Foch was wunder a cloud. Another thing few Americans realize is that only two months after he got the job Clemenceau wanted the Tiger saved Foch—the Tiger, that is, with some help from the Americans. In face of the first great German attacks, Foch, thanks to British tenacity and tardy French reinforcements, had kept the Western front intact, although at terrific cost in allied losses and morale. ‘Where would the next blow fall? Near Amiens, said Foch, disregarding American warnings that it would be far from Amiens, on the Chemin des Dames. So when the blow fell the few and tired allied troops could not be supported quickly enough by Foch’s re- serves coming tardily from around Amiens, and the triumphant Germans ressed down to the Marne at Chateau ’Il,'hlery—anly 40 miles from Paris. Called Blackest Hour. That was what Gen. cony. siders in all 1918 the blackest hour for the allles. Some of the French troops, harried and worn, lost heart, retreated pelimell, some even looting as they went. The allied commander-in-chief had guessed wrong. Officers at his headquarters saw his staff plunged in gloom. Clemenceau came to the rescue. Dashing back and forth between and the rmnt'm wa;re;ley‘ ue‘eglng the TTiger appeared heroic before the Cham- ber o!‘%epnuu, some of whom - ored for Foch's head. “What are you “I fight before Paris!” roared the Tiger. “T lfl‘h& behind Paris! I fight el _Loyally and courageously, he saved y !bchy:h{ and the Americans. For then it was that the 2d American Division, and Marines, came to the Marne at Chateau Thierry through throngs of retreating French peasants— and some soldiers—and stopped the Germans. Legend hath it that they saved Paris as well as Foch, which is <doubtful, buzm '.her”e‘ Was “ou‘;:lm’:‘ Clemencea, se upon as )pa- dlwe“mupmmdlnh‘mu, fl:fi- now that their troops and the had failed them. But, said Clemencesu, here were the Americans, fresh, innumerable—they that they were as good as the French newspapers enthusiastically told them they were. More American divisions thronged to defend Paris: Third, 4th, 26th, 27th, 42d. They helped shatter the last great German offensive of July 16; then on July 18 the 1st and 2d American Divisions formed, with the Moroccans, the spearhead of counter-offensive whereof Foch had dreamed vainly until they came. Pershing Has His Way. Now Foch and Clemenceau could no longer deny Pershing command of his own independent American fighting force, for which he had struggled in- cessantly. The Americans had made possible the victory for which Clem- enceau conferred upon Foch the ex- alted title, Marshal of France, and Foch began to plan the great battle that in the Fall brought the Germans to their knees—although not quite as Foch had planned. Haig, Pershing and Petain had their say. The battle that started ‘September 26 was a series of great converging at- tacks to disjoint and crush the Ger- their vital rail- ormed American rough, heavily fortified, strategically vital Meuse-Argonne region. It started its assault well, but stopped short of the well-nigh incredible victory for which some had hoped. In the heat of war, eager to end it victoriously, some French and British leaders, especially Haig and Petain, blamed our Army, whose staff and com- manders they called too inexperienced to run a big battle. They pointed to our road jams, which Pershing himself stood at crossings trying to disentangle. Partly from pique, partly because they sincerely believed us incompetent, Clem- enceau and Lloyd George embarked upon a propaganda that became an in- trigue to discredit American command in general and Pershing’s in particular. Traffic Jam Rouses Ire. Clemenceau visited the American front, was stuck for a time in a road jam, and arrived at Foch's headquarters boiling. He seldom disturbed the mar- shal at mass, which the old agnostic said “works very well with him,” but this time he exploded: “Those Americans will lose us our chance for a big victory before Winter," he said in effect. “They are all tan- gled up with themselves. You have tried to make Pershing see. Now let's put it up to President Wilson.” The French had thought of that be- fore when they found Pershing stub- born, sticking to the orders President Wilson, Secretary Baker and Gen. Bliss had given him when he sailed, to form an American Army as soon as prac- ticable. He was too ambitious, the French said. But Marshal FPoch knew that the American commander was fimrly set now for an independent American Army. He knew al that any other American commander would be just as set and would be backed by his Army and Government. So what was the use intriguing for Gen. Pershing’s removal? “The Americans must learn some time,” said the marshal to the premier. “They are learning now, rapidly. Every day they will help us more and more. We must play the game with them.” Grudgingly, Clemenceau returned to Paris, but there he told Admiral Sims that the Americans had lost a great chance, because that stubborn Per- shing insisted on trying to run a big battle independently. American Repre- sentatives ~ visiting France took the story back to Was! n. There were whispers that Gen. March would take Pershing’s place. Foch Sends Letter. Meantime, Marshal Foch got from Gen. Petain a proposal which he for- warded to Gen. Pershing in a letter dated September 30, that was as wel- come as a German air raid. The let- ter advised that the whole Argonne Forest front of our battle be given to a French general to command. The moposll did not mean that we should ve fewer men engaged or smaller losses—rather larger, for the marshal wanted us to bring to the Meuse-Ar- gonne more American troops and put many of them under French command. ‘To part of the pro) Gen. Per- shing consented, but not to turning over 100,000 or more American troops and a good slice of an American battlefield to a Prench general. Gen. Pershing and his staff considered the proposal tac- tically unsound and morally impossible. ‘The problems of the Meuse Valley and the Argonne Forest were inseparable, and must be handled by the same com- mander and staff. man armies by cuttin ‘What would be the moral effect if the erican , not the German, should be cut in two in the midst of its greatest battle? The Army and the American people would be explaining all the rest of their liyes. Suppose the school histories today said that we had failed in our first big battle, and the French had to take command? Gen. Pershing’s reply was plain. And s0, on an American battlefield, there started the 10-year feud between Foch and Clemenceau. For Foch dropped the idea, but Clemenceau did not. ‘The Tiger was a bulldog, whose jaws did not slip. The Americans l!m&&d forward once more, then in mid- - ber, paused for a rest and to g"repm for another blow. On Octol 21 Clemenceau wrote to Foch, protesting that he should force the Americans to accept absorption into allied armies, or else get a new commander. Foch did not agree. Suggestion Made Again. Only a few days before the war ended, Clemenceau proposed the same thing to Secret of War Baker, the Paris. So Lord Milner, minister, and, finally, Lioyd George. During the very armistice deliberations Haig made, B 's presence, slurring reference to the Americans, which f- days Foch remained the Americans’ friend and wrote to Pershing: “The accomplishments of the Ameri- can divisions under your orders are too fine for me not to lool !flmr::erg for every o » hatchet going to do?” they | covers it," the upreclmnl one s0 Foch and Clemenceau. ‘The it jdicr had_af- fronted m.mc Prench premier. Foch had singed the Tiger's whiskers by thrusting forward a firebrand idea—that the peace treaty should 'S place military frontier at the. Rhine, that so vasion be EDITORIAL SECTION The Swunday Star, WASHINGTON, D. C, SUNDAY MORNING, APRIL 13, 1930. . Money of the Nation Some of the Problems That Face Successful Operation of Country’s Financial Institutions Made Plain BY LOUIS T. McFADDEN, Chairman. Committee on Banking and Cur- rency, House of Representatives. P73 IRST ‘Three - billion - dollar Bank,” the headlines a nounced a few weeks ago the boards of directors of three New York institutions voted approval of a consolidation. That the combined resources of the merged institution probably will fall short of three billions by two hundred million dollars is not material, for a hundred millions or two hundred mil- lions of resources may be “picked up” almost any time in the bank consolida- tion fleld! The next merger may pro: duce a four-billion-dollar, even a ten- billion-dollar bank—and produce only yawns from the man on the street, who quickly scans the first-page headlines and then folds back to the sporting page for careful perusal and study. ‘The exploits of Babe Ruth may be, 'nnd undoubtedly are, far more interest- ing to the mythical “average man” than the exploits of America's great finan- clers. Yet what is now going on in the banking field throughout. not only our Nation, but the entire world, is of direct concern to every American who has a living to earn. The average man and the average woman are not ordinarily interested in banking problems as long as there is a bank—no matter what kind—conveniently located where a pay check may be cashed without burden- some formality or a modest savings or checking account carried. It is only occasionally, in the large cities of the country, that the banking problem becomes visible to any large number of people. Then there may be & long line of people waiting hopefully, and axlously, too, for bank doors to open, because of the word-of-mouth —Drauwn for The Sunday Star by J. Scott Williams. rumor they heard the night before that the bank was “in trouble.” Very much more often those lines— sometimes clamoring mobs—form in the smaller cities and the villages of America. At least 437 times last year their wait was unrewarded, for the banks had failed. The wives of work- ingmen forgot their own losses of quarters and half dollars laboriously saved for deposit in Christmas accounts while consoling their husbands at Christmas time over the loss, through the same bank faflure, of the few hundred dollars accumulated to make the first payment on a home. School teachers, grown gray after long years of service, found that the savings in- tended to make their old age secure had suddenly vanished with the post- ing of a little white sheet of paper on the front door of the “Security Savings Bank,” bearing simply the words “Closed by Order of the State Super- intendent of Banks.” Business men and children, the aged and the young and prosperous, suffered alike when those 437 banks suspended or failed in the wx 1929 with labilities of $218,- 000,0 ‘This situation, however serious and distregsing it is, presents only one phase of the banking problem, and not the most important one. The great ma- jority of the banks of the Nation are in sound and solvent if not prosperous condition. The stock market colls ,of last Fall produced surprisingly bank faflures. There was not, and is not now, any general shortage of money or bank credit. ‘The banking problems we confront now are not, in their essence, “new.” (Continued on Fourth Page.) Guiding the Mob Mind Mass Suggestion Is Directing More-and More of Our Thinking—New Ethical Standards Likely BY DR. WILLIAM A. WHITE and MARY DAY WINN. HROUGHOUT folk lcre runs the theme of the god or king who is told by soothsayers that at some future time he will be killed by his own offspring. Scientific inventions--radio, airplanes, television—are the most brilliant chil- dren of modern civilization, and, look- ing at them with the prejudiced pride of creation, most of us can see no evil in them and no danger. Yet any one of them, like the son of the old tales, may grow up to destroy us if we do not, keep our eyes open to all its possible influ- ences and lasmlm counteract its de- structive tendencies. Modern machines are turning the population of the world, psychologically speaking, into a mob; in that fact is danger as well as opportunity, since the collective_intelligence of any group of people who are thinking as a “herd rather than individually is no higher of the sti st than the lnulél:e;:; b !;&X pr intolerant, prone to exa ing in nt:'orpluimm ibb u;yél’mgnd by em A to a leader, and—what is very impor- suggestible. en in | f ter he withdrew. In those last | Of the rs A the first person who knew about it talked to a reporter. Hundreds Beset With Fears. On reading the resulting news items hundreds of people throughout the beset |.the bosom of another way of thinking is some common in- u:e’n, some common ambition or emo- Since the herd mind is 3 hly sug- feevmb!a. the first result oth:ge sflr{g: er news item was that individuals who read it decided that v ac contracted the stra: THE UNIFYING POWER OF HATE IS RECOGNIZED BY CERTAIN POLITICAL ORATORS. had it were suffering from nothing more unusual than hysteria. “At a cotton manufactory at Hodden Bridge, in Lancashire, a girl, on the 15th of February, 1787, put a mouse into fil‘l. who had a great dread of mice. The girl was im- mediately. thrown into a fit and con- tinued in it, with the most violent con- MA, for 24 hnux's’.! lIlonflt.ls.:e mmivx; three more were seized m5 same manner, and on the next six re. “By this time the alarm was so great that the whole works, in which two or three hundred were employed, was to- tally stopped, and an idea prevailed that a .f"""" ar disease had mn- troduced by a bag of cotton opened in the house. On Sunday, the 18th, Dr. St. Claire was sent from Preston. Be- fore he arrived three more were seized, and during that night and the morn- ing of the 19th 11 more.” caused by mass suggestion are enon. have oc- gives an interesting description of one which took place in the latter part of the eighteenth century. The follos account of it is quoted by Dr. Karl Menninger in “The Human Mind’ “Three of the number lived about 2 miles from the place where the diso: first broke 1 at Clitheroe, about 5 miles “The symptoms were , strangu- lation and very strong cons and these were so violent as to last without any intermission from a q of an }aeur to 2¢ hm;rl. and wt :&I:n": ve persons to prevent the from tearing their hair and dashing their heads against the floor or walls. * * * As soon as the patients and the country were assured that the com- plaint was merely nervous, easily cured and not introduced by the cotton no fresh person was affected.” Coming down to modern times, we may witness many similar examples af estibility. Every liowed by others in the same manner. great murder trial, which serves to throw the public into & herd way of thinking because of its common interest in the fate of the defendant, causes a number of entirely innocent people to confess to the crime, backing up their confession with the moot circumstantial details of just how they did it. While the Leopcid and Loeb case, with its account of kidnap- ing and cruelty, was being given so much space in the newspapers, several Chicago families received threatening letters telling them that if they did cr did not do this or that thing their chil- dren would be .stolen. A more cheerful example of mob sug- gestibility was the embarrassment of gifts which were showered on Col. Lindbergh after his famous exploit. The Nation was drawn by its common admiration for the hero into a mob state of mind, and hence was highly suggestible where he was concerned. News accounts of the first gifts sug- gested more. These in turn, publicly reported, suggested a fresh outburst of fenemslzy and’so on until the accumu- lated collection required a special house to hold it. Suggestibility, however, is by . no means entirely evil or frivolous in its results. It is, in fact, the quality in human nature which makes all_social life possible. If no man could influence the action of any other except by force or fear, we should probably still be sav- ages, lonely and antagonistic units wan- dering in forests. Common interests, aided by suggestibility, have us together, and the tendency of modern civilization is to stre n these bonds of interest and to weld us into ever larger and more closely bound groups. Apartment houses, co - operatives, trusts, chain stores, combines, labor unions—these are all indications that ‘we are acting more and more as crowds Bisis:viene & great experiment in co- ussia, where a great e: ent in co~ operative living is being tried, individual thinking or acting is a crime some- times ishable with death. Even in countries where individual thinking is not legally penalized, it is often difficult, rder | if not dangerous, if it happens to run out, and three at another counter social 0. ge accepted A growing nrtm of tolerance flum lucated classes is more the way from our fellow man, a h was strikingly illustrated newspapers carried a few g0 the pictures of Dr. Friederech Ritter and a woman friend. Beeklnfinw these two had fled secretly from Berlin and taken refuge in a yonl}ehmAnd of the Gala- pagos group. no purpose. The members of the McDonald expedi found them there, and before long their adventure was the common property of w'd people on ”t_w continents. numbers of persons into % state (Continued on Page.), h STIMSON HAD TO FORGET REDUCTION FOR PARITY Naval Figures for 1936 Reveal 25,000 Increase in Cruiser Tonnage. ——- BY FRANK H. SIMONDS. S a consequence of the publica- tion of the details of the American -Japanese agreement it is now possible to set forth in their final form the figures of the American fleet as they will be fixed in any treaty which may emerge from the London Conference. We know now not merely what the aggregate total tonnage will be but the exact division into categories, But before turning to these figures it is essential to make certain general observations, because the public mind has been inevitably confused by the conflicting and contradictory assertions which have been put forth, together with endless rows of meaningless statistics. Actually what will the treaty of Lon- don—assuming that there be one—mean in_terms of naval strength? It will mean precisely this: That the United States is going to scrap some 170, 000 tons of obsolete and obsolescent ton- nage, distributed among capital ships, destroyers and submarines, and in place construct an equal amount of tonnage— 125,000 tons allotted to new, modern types of cruisers and 45,000 tons of air- plane carriers. At the end of the process she will have almost identically the same total tonnage, but con- comitantly she will have a fighting fleet incalculably more efficient and effective. Moreover, all the tonnage which the United States is going to dispose of would have gone to the scrapheap, con- ference or no conference, by the mere operation of the age limit. And in the actually important category—namely, cruisers—she is going to undertake to build at least 25,000 tons more than were foreseen by existing legislation, inclusive of the 15-cruiser act. Sent on Hopeless Errand. ‘These figures must serve once for all to demolish the preposterous notion that the United States could have both parity with Britain and reduction in naval strength. When Mr. Hoover at the farewell breakfast commissioned Stimson and his associates to make re- duction the chief objective of their mission he sent them on a hopelessly impossible errand. At the Rapidan Macdonald had supplied the bottom figures of the British admirality, and they involved the addition of not less than 125,000 tons to existing cruiser strength in the American Navy. ‘The rather pathetic attempt of Stim- son—under pressure from Washington provoked by the famous petition of the 1,200—to demonstrate that reduction was contemplated finally exposed the whole truth: which was that the United States might have parity or reduction, but that it had to choose one. Since that moment Stimson at London has confined himself to the search for par- ity and reduction has gone by the board. Now as to the figures themselves, as disclosed by the Japanese agreement. The following table sets these forth, the 1930 figures being taken from of- ficial naval statistics, the 1936 from the Japanese agreement, which has now been duly published. Submarines 74,000 tons 11124,000 tons 1,124,000 tons. Reduce Battleship Tonnage. Now examiné these tables and what is revealed? The United States is go- ing to reduce her battleship tonnage by 71,000, which means three ships. These ships would have disappeared- in any event before 1936. Under the Wash- ington treaty she was free to replace them by two boats of 35,000 tons each. But France, Italy, Japan and Britain have all resolved to build no more of these craft. American naval experts are against replacement now, when the whole question of the capital ship is in the balance. In the same fashion the United States is going to reduce destroyer ton- nage from 227,000 to 150,000, but actu- ally this means no more than getting rid of a flock of old destroyers which were hurriedly constructed to meet the German submarine menace. Many of them are already obsolescent and there was no demand to replace old tonnage by equal strength. The United States was simply overstocked in destroyers and was bound to let her tonnage fall to 150,000, the London figure. And the same is true in American submarines; reduction was automatically imposed by age limit. On the other hand, in the two live categories, cruisers and airplane car- riers, the United States contemplates expanding in the former category by 125,000 tons, in the latter by 45,000 tons. And the cruiser expansion will carry her 25,000 tons beyond the total envisaged in the 15-cruiser bill. But even with this enormous expansion she will not have tonnage equality with the @ritish, who will have 339,000 tons, nor will she have parity in numbers, for the British total will be 50 and the American but 36. This considerable gap is to be bridged by American pos- session of three more 10,000-ton eighte inch-gunned boats than the British. ‘Well Rounded Fleet. Assuming that there is a trealy at London and that it is ratified by the Senate, the United States will have in 1936 a well rounded. fighting fleet, a modern, efficient instrument of war. She will get it by an enormous scrap= ping of the obsolete and an equal con= struction of the effective. The process will cost not less than $1,000,000,000. The point is not that the London Conference has imposed this program— such a conclusion would be absurd. The significant fact is that, conference or no conference, if the United States wanted an efficient navy, a navy equal to the British, this is what she would have had to do in any case, and the conference has left the situation un- changed. What has been absurd at all times has been the idea that the London Conference could bring about any re- duction as long as the American people demanded parity with Britain and the British people demanded a two-power standard vis-a-vis France and Italy. And the same reasoning applies to the Italian demand for parity with France and the French demand for a two-pow- gr lsundard vis-a-vis Germany and taly. The London Conference is going to result in the adjustment of the fleets of the five great sea powers in accord= ance with the necessities of the next war, as the experts in all countries see the technical nature of that conflict. By 1936, when the treaty of London will expire, all the fleets will be re- organized and reconstructed on this hasis. Reduction will not occur in any case; limitation will come only on the basis of the financial conditions and immediate political and strategic posi- tions of the various countries. Vast Expenditures by U. S. Parity between the United States and Britain will arrive, but at the cost of vast expenditure by the United States. This always was inevitable. But if a three-power instead of a five-power pact is made, then at once, or shortly, it will be necessary to add 85,000 tons to both the British and American totals and 60,000 tons to the Jspanese. This increase will result from the British determination to main- tain a two-power standard vis-a-vis France and Italy and the French de- termination to carry out their present building program. And it is the uni- versal recognition of the political perils of such an expansion, fatal to the Rapidan agreement, that explains the last-ditch fight in London for a five- power treaty. Returning from London, I find a widespread tendency in the United States to blame the European nations for the utter failure to arrive at any reduction in fleets. But such a charge is totally unjust. There is no better reason why the United States should have parity with Great Britain than why Britain should have a two- power standard: in Europe, France a two-power standard on the continent and Italy parity with France. ‘Would Have to Build 100,000 Tons. All of these respective national de- mands involve naval construction and preclude reduction. And the American demand for parity with Britain involves the largest and most expensive con- struction of all. To get immediate parity the United States will have to build a vast new fleet of cruisers, and to maintain it, if a three-power treaty is made at London, she will have to add nearly 100,000 tons to the Rapidan ures, To ask the British to reduce their navy beyond the two-power standard in Europe, which {s the basis of British security; to ask France to modify her naval construction program, which is the French estimate of national safety; to ask Italy to resign her demand for parity with France, which is a question of national honor, simply that the United States may have cheap parity with Britain—may have equality with- out expense—was always unreasonable. If anybody believed that the Kellogg pact had opened a new phase in post- war history, that, thanks to it, a naval conference could bring about reduction or even real limitation in naval arma- ments, the answer is written in the figures each nation has laid on the teble and subsequently maintained to the bitter end. London has not so far provided for bigger navies, but it certainly has made certain better navies. If the “‘unthinkable” war should come in 1936 the naval officers of all countries would have every reason to be grate- ful for what was done at St. James' Palace in the name of peace, parity and reduction. (Copyright. 1930.) Plan to Rebuild Ancient Nanking, Making It Beautiful, Modern Capital ‘The task of rebuilding an ancient Chinese city of narrow, meandering streets and poverty-stricken hovels into a beautiful capital is the problem con- fronting the Nanking City Planning Bureau. Since the Nationalists designated it as the capital of China as a tribute to the revered Dr. Sun Yat-sen, Nanking has been increasing in population at the rate of 100,000 annually. The census of 1928 was 497,500, and it is estimated that by the end of the present century the city will have a population approxi- mately 2,000,000. This expected growth is being taken into consideration by the ition | Institute, City Plannnig Bureau, which is laying out the various city centers. Plan Political Center. ‘The political center will be situated south of the foot of Purple Mountain, Wwhich is the site of the mausoleum of Dr. Sun Yat-sen. This location will be near the new rallway central station, which is to be built west of Purple Mountain and will include within its Righways lnking the capital with Hang- ways e ca - chow, 8| hai and cglnvkhn;. ‘The municipal center will be northeasf of the famous Drum Tower. According to the architect’s drawings, the munic- 1 will be grouped in a| circle N central building. This building will be intersected by roads run- nl;‘-nsldlmmny like the spokes of a Wheel. Near a famous hill known as Wu Tal Sen, the culture center will be located. ‘The gll:na include a public library, lec- ture hall, museum, stadium and recre- ation ground. National Research now in Shanghai, will be re- moved to the culture center of Nanking. New Educational Center. e or. e educaf cilities of the new capital. Most of the schools will be in the educational center, which will be near the residence sec- tion of the city. ‘The residence center is one of the most immediate concerns of the Plan- ning Bureau. A great scarcity of houses may be attributed to the remarkable in- crease in population since the city be- came the nation's capital and because a frnt many homes were destroyed in building the Chung Shan Memorial Highway, which connects the city with Purple Mountain. This was built as a memorial to Dr. Sun. Chinese Exteriors. The style of the government and pub- lic buildings to be erected in Nanking will follow Chinese models as to exterior, but will incorporate Western architec- tural ideas in their interiors. Provision has been made for an in- dustrial center three miles from Nan- king, where it will be convenient to the rallway as well as to Nanking Harbor. The municipal government plans to oFR odern water works GtiiHing Fenes rater works uf ang- tze River water. ottt £ reconstruction for the new capital totals $50,000,000 > currency. Seeking French Name For American “Talkie” What shall the word “talkie” be in French? 1In order to avold having 1o use the English word, various sugges- tions have been made in Paris, an:‘ tel:a Echo de Paris is conducting a contest for the best one. More and lish words get into the French language thue‘dniy;.b wm llnec I:h': be drawn, 30 say , 8 “talkie.” B‘fb the substituf S adduced seem barl