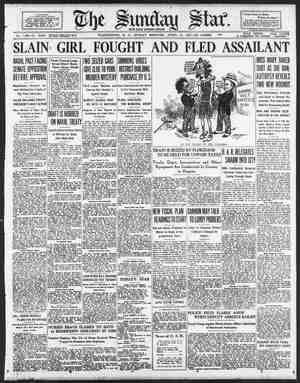

Evening Star Newspaper, April 13, 1930, Page 89

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

The submarines were obeying the allied orders, coming to them in their own code—and before the Germans could change the code, more subs were sunk in one week than in any week before. German Submarines Suffered Worst Losses During World War Obey- ing Faked Code Messages— De- = ciphering Clever Secret Codes. Finding Out If the EnemyWas Listen- ‘ang In—"The Work oy the Censors. W '\'..“ l-—-“‘ - L -3 c pt. Bj’ o 4 Thomas M. Johnson. e 1 (FAMOUS W AR CORRESPONDENT.) 14 EDITOR'S NOTE: This i5"one of & series of true World War spy stories. In some instances the author 1as used intentional imnaccuracies, to protect Amere § can secret agents: otherwise the information is au- /henticated by fact or by word of participation. “V4E possibilities for trouble were infinite in the mail of the two million poly- glot youngsters, mostly inexperienced in war, who made up the A. E. F, But it remained the most loyal army 1 iIn American history. Its base censor de- y tected only one real case of disloyalty, and 1 shat was exaggerated largely because the press censor censored the base censor and forbade ¢« publishing particulars, even in the Stars and ] Stripes, which called it a “spy case.” ¢ The real facts have neve been published. ' They are: Capt. Lusien J. Desha, in charge of ' the testing laboratory of the base censor’s office, found messages written between the lines of two letters, with fruit juice, and with a steel pen. It was a crude job, for oxidation had made evidence of writing apparent be- fore the letters reached the laboratory. Both letters were written, on paper furnished free in Red Cross and Y. M. C. A canteens, by Joseph Bentivoglio, a private soldier. His secret messages to relatives in Italy were about like this: g “Things are bad here. The food is poor. Do not believe what the newspapers tell you. We are all getting Xkilled!” Ao Al The soldier was court-martialed. His own - ignorance was proof that he was no spy. Many others, smart-Alecks or careless, made un- malicious efforts to slip something by. As Maj. B. A. Adams reported: *~ “We have discovered many attempts at the conveying of forbidden information to satisfy the curiosity of friends and relations at home. This information was usually the location ot the writer, the troops near him, and where he was to go, ordinarily in some easily de- tected code. In a few instances, it was con- veyed by invisible inks.” Mail censorship turned up other things, as this true story shows: . German-born soldiers in the A. E. F. caused G-2 puzzlement. Should they be sent to the front> G-2 advised the War Department to send to France no more than necessary, and gave those already there a choice, front or S. 0. S. Quite a few took the front, and did splendidly. But only naturally, censors watched letters directed to German names. | NE such raised some question abeut a sergeant of American Cavalry stationed only 16 miles from Chaumont. Investigation re- realed that he had come from the Coast Artil- ery where he had shown high mechanical pro- THE SUNDAY STAR, WASHINGTON, D. C, APRIL 13, 1930. Fake Messages and Secret Codes O?-éi)ies The last great Zeppelin raid was & failure an% most of the fleet had to come down, one way or another. One landed at Bourbonne-les-Bains, in the Ameri- can training area—and Americans were aboard to seize its code-books befora the crew could destroy them. THE FIRST AMERICAN PRISONERS, When Germany heard that Americans had at last arrived in the front trenches, according to the French intelligence service, they offered a substantial reward to the first German soldier to take an American prisoner. On the night of November 2d, 1917, a hundred Germans raided the Americans near Arracourt and dragged away 12 men, leaving behind three dead and many wounded. German authorities were excited. High officers, including the Crown Prince, questioned these 12 Yanks. What did America plan to do? How many soldiers were coming over? And why were Amer- icans fighting Germans? “To free Alsace-Lorraine?” said the Americans. “What is Alsace-Lorraine?” “Guess it’s a big lake somewhere over Rere,” they replied. Were the doughboys playing dumb? Whether or not, the 12 were happy-go- lucky Terans and the Germans gained little information from them. ficlency. A look at his record showed a model soldier, a look at him showed a typical Pruse- sian, perfectly disciplined, with an officer’s face, not a sergeant’s—and only 16 miles from G. H. Q! He resisted for two days Col. Sigaud’s stiffest questioning and then told this story: “I am the Baron von Schrack, of a family well known in the Fatherland. Long before the war began, I became a lieutenant in a crack Ger- man regiment. I drank and gambled, and finally embezzled mess funds. They let me off— —on my promise to join the secret service. I was trained at Charlotenburg, as a military and naval spy, to go to England. I learned that a World War was inevitable. I tried to get out of the secret serviec, and they threat- ened to kill me. So when ordered to Eng- land, I went—and took the first ship for the United States. In Detroit I enlisted in the army; and.there I have been a loyal American soldier.” G-2 sent him home, where his story stood the test, and Baron von Schrack kept his as- sumed name and American uniform, not as a sergeant of Cavalry—but as a captain of Mili- tary Intelligence. Mail censorship here helped catch the only spy condemned to death in this country, Pablo Waberski, Several letters were detected from and to real German agents in this country or in Mexico, whence most of the spy activities were directed after we entered the war. Ome enigmatic message remains unsolved, from & Spaniard in New York to a German in South America: “Where is the Cyclops?” Why he should have asked news of the lost Navy col- lier remains as mysterious as the ship’s dis- appearance. i Though counter-espionage nets kept spies pretty well out of the A, E. F., mail censors detected some quite loyal in acts that would have helped spies or evaded regulations. They turned up 1,042 cases for disciplinary action, including a .major who presented a charming welfare worker with a box of blank envelopes stamped in- advance, “Passed as Censored.” She could write anything she liked. One officer at the front wrote a girl at home that an earlier letter “fell into the hands of the base censor and that poor slacker had to do something to justify his existence and sent it back to me.” The second letter reached the same censoring officer, recuperating - from wounds, decorated for gallantry, and greatly to his delight it also violated censorship rules. The writer got what was coming to him. Ir Napolean thought an army fought on its stomach, Foch thought it fought on its morale. The best way to find out about both in any particular lot of doughboys was to read their letters home. In them they told of troubles, if they had any—sometimes, if they hadn’t. This helped find remedies for the post-armistice slump, as suggested in these extracts from letters of doughboys on leave at Aixles-Bains, ‘Biarritz and other famous Prench resorts. . “I shure have seen some reel sites...I seen a lot of places that people paid a grate deal to see but of all the sites I seen, the one that got my gote was a man that had been dead 5,000 years. That is, they say he has.” “This place used to be the big hangout for Ferdinand and Wilhelm, Alphonse and all those small town guys so naturally when the natives see @ regular guy like me, they go wild. The girls here are the finest I have met in Prance.” “Tell dad to buy a lot of Liberty Bonds, cause Uncle Sam needs the money to give his boys a good time.” But such enthusiastic letters went mostly from leave areas. When Gen. Pershing told Marshal Foch soon after the armistice that he knew the doughboys wanted to go home, they had told him so, through the base cen- sor. Besides forbidden military information that office sought in their letters information bear- ing on their morale, their feeling toward pub- lic questions, any irregularities or abuses from which they suffered and suspicious persons. The most dangerous mail was that to neutral or allied countiies. Letters home were less dangerous—they took too long, as all doughe boys will admit. There was more than one way to get the enemy’s code book. THI base censor received 30,846,630 letters and examined 6,335,645, His office in Paris was always understaffed even with 33 officers, 183 men and 27 civilian employes. The chemical ‘laboratory was not established 1918, and examined for secret Mk, 53,658 T i Eésfi Egé E [ zaifa:s! censored im his own outfit sgd went right through te transports without tarrying with the base gensor. The base censor says that those that did come, were delayed at most only 48 hours! Packages were censored as well as letters. - They might contain those ingenious German lneendhrypenclh,oneeflupectodolml fire at G. H. Q, or even spy messages. : ed, and messages were found in' false bottoms of boxes, in tobacco, soap or cans of preserves, and between the glued sheets of & photograph of some loved one. Newspaper advertisements became so com- mon a means of sending or gathering informa~ tion that many counter-espionage services in- vestigated every one before it was published. An agent within the enemy country woul insert in a newspaper, preferably near . some neutral border, an apparently harmless ad- vertisement containing a coded message. A few days later, his team captain in the neutral country would read that advertisement. . The old style “agony column” notice in the London Times afforded scope, and what seemed lovers’ quarrels ‘had a double significance. Here was one real one: “Z. Your heart watches. Be very good. No more. My God what a weariness. I can not come tomorrow.” It meant: “The government will float a new loan. There will mo longer be a ministry of concentration.” And this one in an Italiaai newspaper: “Wanted: A fine furnished room, detached, modern comforts, centrally located, price mod- erate. Answer Cortl.” Meaning: “‘General Italian offensive in view. Italian troops not being transferred to Franoce.” Censors forbade newspapers . publishing -lottery numbers, chess games and stamp data, but were stumped when they realised what could be done in signaling with stataps on an em- velope. THE British stopped the advertisements of & German agent in Londem, Hugh Mec- Kean, of cheap horoscopes'fr noldiers at the front, that required a return address. The Continued On Twenty-first Page