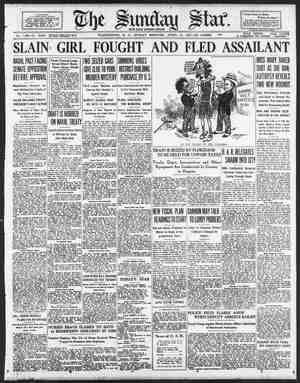

Evening Star Newspaper, April 13, 1930, Page 88

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

Smiling Harry Sinclair, who paid more than $1,000 a day in maintaining his big racing stables at a time when he had 210 horses. BY GILBERT SWAN. g £ ; !EE fic E i E i IR : | FEe o HIT I HEL fentiglities. For there is no greater gamble under the sun, Two hundred horses may be @isposed of in this auction, and but two or three may ever be heard of again. Millions will be spent on prospect, and only a few thou- sand may come back to the pockets of the in- Romance and glamour hang over the & ] [ -3 i g 4 sk 5 i £2 i €3 en : thousands through the The children of this horse of been many, and valuable. Most made excellent names for them- ¥ il There for instance, Crusader, which had brought Sam Riddle: more than $166,000 a THE - SUNDAY STAR, WASHINGTON, D, C, APRIL 13, 130 MILLIONS FOR A HORSE How American Kings of Finance Follow the Sport of Kings, Sinking Fortunes in Colts, Training Them and Keeping T. hem in the Races—Often W ithout Betting a Dime on Ponies of Their Stables. Y/ Peddled off for $5,000, Man o’ War, pictured with his owner, Samuel P. Riddle. fords, which grabbed off the hotly contested Belmont Puturity for 3-year-olds. Those are but & few of Man o’ War's illustrious sons and grass belt, where they have been kept on the farm of Elizabeth Daingerfield. There was, too, was somewhere around $12,000. horse had brought in the Derby purse, Hertz spent something like $50,000 to prove he had the world’s speediest racer. He sent Reigh Count to England in a special stall aboard the Minnetonka. This ship stall was pneumatically padded and an insurance of $250,000 was taken out against possible misfortunes. Yet Reigh was refused. John Hertz remained loyal to his favorite. One of the biggest “money horses” of them all was Blue Larkspur of the Bradley stables, which showed total earnings of $220,000 not s0 long ago and was credited with grabbing off some $135,000 worth of prizes in a single season. And there was that excellent money-making Anita Peabody, perhaps the most prosperous 2-year-old to turn out on an American track. Her price was $11,000, but in the 1927 season she had taken ten times that amount in prize money—=a consistent winner. BU‘!‘ for every big winner of this type there have been hundreds that barely paid their stable keep, or not even that. And keeping the sport of kings alive involves a somewhat breath-taking expenditure. To begin with, figure that the average stable that pretends to be a stable has from 10 to 40 horses. The general average would, perhaps, be about 20. ‘The initial cost of getting such a stable together, what with stake horses, sell- ing platers, handicaps, 2-year-olds, assemblers. . and the 1test, involves more than $150,000. Then the upkeep. Each horse is maintained a day. It can be estimated that ! about $10,000 or more a year, and Laverne R g man stables have consider- ably more than 20 horses. The Whitney sta- bles have held from 75 to 200 horses at one Harry Sinclair had, at least a year or some 210, which even on a farm ran up a cost of more than $1,000 a day for main- ce ate his own stable at one time but found he 't make it go. 8o he returned to riding. Now and then the stables do show a profit. The 1928 record price of $75,000 went to a colt of Whiskbroom II, and Harry Sinclair did very well that year when his great horse Zev beat Papyrus in the international race at Belmont. This amazing performer brought to the Rancocas stables some $450,000. But, however you figure the various win- nings, it remains a losing game. Statistics show that for every $750,000 which changes hands at the Saratoga paddock sales an amaz- ingly small percentage ever comes back to the pockets which put it out. But how about the betting, you naturally ask. Believe it or mnot, an extraordinarily small amount is ever wagered by the millionaires who send their favorites to the posts. The wager- ing is left to the grandstand crowds. Whitney, for instance, rarely backs his own mounts. The same goes for Widener, Harriman, Mar- shall PField and the rest. When bets are made they are generally so small that little difference is made one way or the other. There have, to be sure, been a few individual violations of this unwritten rule—but not many. Their thrill does not come, as it does with the crowd, from having money up on certain horses. They are content with the thrill of seeing their stable colors bring home a silver cup, a purse and a huge horseshoe of flowers. The late Sam Hildreth, one of the track’s most picturesque figures, liked to plunge a little, however. A colorful character, who still lives in the track-side tales, Hildreth was ex- tremely superstitious. about the mounts on which he was wagering. v . From 75 to 200 horses are always in the stables of Harry Payne W hitney. For instance, he would never allow a news- paper cameraman to photograph one of his favorites before a race. I recall one occasion when a canny picture grabber managed to “steal” a shot. Hildreth, feeling that this would prove a jinx, scratched the horse at the last minute. ANY tales also cling to that grand ol racer, Exterminator. It was said by his jockeys that here was one horse that never was really “ridden.” A jockey once told me that if one were to put & sack of lead on the stable, equivalent to the weight of a jockey, Exterminator could make the grade just the same as if he had & rider. He knew when to fall back, when to pick up, when to nose his way through, and when to begin his finish plunge. The wise rider never tried to force this horse nor to direct him. It was the jockey's business merely to sit in the saddle and let this shrewdest of racers take care of himself— which he almost invariably did. The smaller and precariously maintained stables have to fall back on chance taking, with several of them notorious for quick clean- ups and manipulation of horses in an effort to build big odds for a final clean-up. There are many stables barely able to “make their feed,” which provide horses for the smaller tracks, and ofttimes do well enough to make eventual appearances in the “big time.” They cannot, like the millionaire sports- men, afford to take a chance on the purchase of yearlings. T is from this latter source that a consid- erable income is built and some return om the huge investment realized. During the past racing season, for instance, the Whitney farm sold about 25 yearlings at a price of $150,000. The Wheatley stables were- the chief buyers. Another big buyer was the “Warm Stables,” which is relatively new to the race world, backed by Silas Mason’s money, Three of the horses in this latter purchase were Victorian, which made a neat name; Cady Hill and The Nut. Before the year had ended Whitney had some real cause to realize the caliber of horses from his own farm, for The Nut beat Whitney's own favorite, Beacon Hill, in the Realization Stakes race. It is figured that Whitney’s racing and breeding investe ment would undoubtedly reach close to $10,« 000,000. In the list of horsemen who have built for- tunes from breeding, training, trading and racing horses, the late John Madden was cer- tainly unique. A shrewd trader, and a particularly keen horseman, he seldom made any mistakes, and as a result of his uncanny wisdom, his repu- tation was international. The jockey role of honor belongs over a period of time to Earl Sande, though he has not been consistently active on. the tracks of late. His 1926 record, however, showed him bringing in $240,000 in purses. Laverne Fae tor, Johnny Maiben, McAtee and Johnson are also high in the purse-winning lists. But that's all past tense. Each Spring brings its assortment of “dark horses” and bril- liant riders; its buying and bickering and bet= ting; its overnight changes in dope—and that's why the hobby-riding millionaire kings of sport find an endless allurement in tossing away their millions on the sport of kings. (Copyright, 1930.) Lave