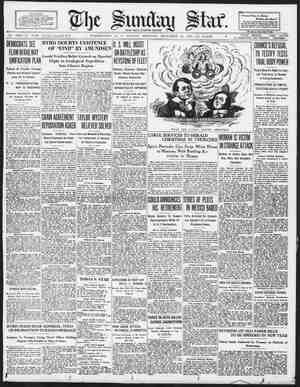

Evening Star Newspaper, December 22, 1929, Page 92

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

The Passing of Mr. Whidden Is a Strange Affair, and This Is One of the Reasons Why This Particular Story Was Given One of the O. Henry Memorial Awards—Another Complete Prize Story Will Appear in the Magazine of Next Sunday’s Star. ROM the street below came that most terrifying of sounds, the full-chested roar of two men shouting, “Extra! Extra!” through the rainy night. “Exta! Extra!” Mr. Whidden, reading his evening paper, wondered what was the trouble. He could gather nothing from the ominous shouts that assailed his ears. The two men might have been lusty-lunged Russians for all of him. But there was an ominous note in their voices— the warning of dark calamity—the grim sug- gestion of wars, plagues, holocausts. “Where do they get those men with voices like that, and what do they do between extras?” he thought. Mrs. Whidden emerged from the kitchen, whither she had retired to bathe the supper dishes. “There’s an extra out, Ray,” she announced. *“So I hear,” said her husband, who was not above an occasional facetious sally. She walked over to the window, opened it, and thrust her head out into the rain. In the street, five stories below, she could see the two newsvenders. “Extra! Extra!” Mrs. Whidden turned from the window. “Something must have happened?” TH.ERE was an overtone of complaint in her ! remark that Mr. Whidden recognized only too well. It was a tone that always suggested unwelcome activity on Mr. Whidden's part. He wished that she would came right out and say, “Go downstairs and get the paper,” but she never did. She always prefaced her commands with a series of whining insinuations. “I wonder what it was?"” she asked, as though expecting her husband to know. “Oh, nothing, I guess. Those extras never amount to anything.” Mrs, Whidden turned again to the window. “Something awful must have happened,” she observed, and the counterpoint of complaint was even more pronounced. Mr. Whidden shifted uneasily in his chair— the one comforiable chair in the flat—the chair which he himself had bought for his own oc- cupancy and about which there had been so much argument. He knew what was coming; he didn't want to move, and walk down and up four flights of stairs for the sake of some information that would not affect his life in the remotest degree. “Don’t you intend to find out?” asked Mrs. Whidden, and it was evident that she had reached the snappy stage. Her husband knew that, if he didn’t go down and buy that paper, he would provide fuel for an irritation that would burn well into the night. Nevertheless, that chair was so comfortable, and the weather was so disagreeable, and the stairs were such a climb!. .. “I guess I won't go down, Emmy. Those extras are sometimes fakes, anyway, and, be- sides, if it is anything important well find out about it in the morning paper.” The roars of the men shouting “Extra! Extra!” reverberated through the street, beating with determined violence against the sheer walls of the walk-up apartment houses, shud- dering through the open window of the Whid- den’s living room, jarring the fringed shade of the reading lamp, the souvenirs on the book shelves, the tasseled portieres that led into the little hall. “You're just lazy, Roy Whidden,” said Mrs. Whidden. “You sit there reading your paper— night after night—night after night.” She turned as though to an invisible jury, to whom she was addressing a fervent plea for recognition of her prolonged martyrdom. Then, with all the dramatic suddenness of an ex- perienced prosecutor, she snapped at the de- fendant: “What do you read, anyway? Answer me that! What do you read?” MR. WHIDDEN knew that the question was purely rhetorical. No answer was expected. “You don’t read a thing. You just sit there and stare at that fool paper—probably the death notices. When anything important hap- pens, you don’t even care enough to step out into the street and see what it is.” “How do you know it's important?” - Mr. Whidden inquired, being inclined, albeit un- wisely, to display a little spirit. “How do you know it isn’'t?” Mrs. Whidden back-fired. “How will you ever know any- thing unless you take the trouble to find out?” Mr. Whidden uncrossed his legs and then crossed them again, “I suppose you expect me to go down and get that paper,” cried Mrs. Whidden, whose voice was now rivaling the news-venders’. “With all I've got to do—the dishes, and the baby’s 10-o'clock feeding, and...all right! Il go! T'll walk down the four flights of stairs and get the paper, so that your majesty won’t have to trouble yourself.” There was a fine sarcasm in her tone now. Mr. Whidden knew that it was the end. For seven years this exact scene had been repeating itself over and over again. If there had only been some slight variation in his wife’s tech- nic...but there never had. At first, he had tried to be frightfully sposting about it, as- suming the blame at the first hint of trouble and doing whatever was demanded with all possible grace; but that pose, and it had not been long before he admitted that it was a pose, was worn away by a process of erosion, a process that had kept up for seven years— seven years of writing things in ledgers in an airless office on Dey street; seven years of listening to those endless scoldings and come plaints at home. Whatever of gallantry had existed in Mr. Whidden'’s soul had crumbled be- fore the persistent and ever-increasing waves of temper. He know that now, if he gave in, he did so because of cowardice and not be- cause of any worthily chivalrous motives. He threw his paper down, stood up, and walked into the bedroom to get his coat. Little Conrad was asleep in there, lying on his stomach, his face pressed against the bars of the crib. Over the crib hung a colored photograph of the Taj Mahal, a “lovely, white building that Mr. Whidden had always wanted to see. He also wanted to see Singapore, and the Straits Settlements, and the west coast of Africa, places that he had read about in books. He was thinking about these places, and wondering whether lttle Conrad would ever see them, when his wife's voice rasped at him from the next room. “Are you going or will I have to go?” “I'm going, dear,” he assured her, in the manner of one who is tired. “Well, hurry! Those men are a block away by now.” Mr. Whidden put on his coat, looked at little Conrad and at the Taj Mahal, and then started down the stairs. There were four flights of them, and it was raining hard outside. TWELVE years later Mrs. Whidden (now Mrs. Burchall) sat sewing on the front porch of a pleasant house in a respectable suburb. It was a brilliantly sunny day, and the hydrangeas were just starting to burst out into profuse bloom on the bushes at either side of the steps. “And do you mean to tell me you never heard from him?” asked Mrs. Lent, who was also sewing. . “Not a word,” replied Mrs. Burchall, without rancor. “Not one word in 12 years. He used lo send money sometimes to the bank, but they'd never tell me where it came from.” “I guess you ain't sorry he went. Fred Burchall’'s a good man.” “Youd think he ‘was a good man all right if you could’'ve seen what I had before. My goodness! When I think of the seven years I wasted being Roy Whidden’s wife!” Mrs. Burchall heaved a profound sigh. “Ain’t you ever sort of afraid he might show up?” asked Mrs. Lent. “Not him And if he did, what of it? Fred could kick him out with one hand tied behind his back. Fred Burchall’s a real man.” She sewed in silence for a while. “Of course, I am a little worried about Conrad. He thinks his father's dead. You see, we wanted to spare him from knowing about the divorce and all that. We couldn’t have the boy starting out in life with his father’s disgrace on his shoulders.” Shortly thereafter Mrs. Lent went on her way and Mrs. Burchall stepped into the house to see whether the maid was doing anything constructive. She found her son Conrad curled up in a chair, reading some book. “You sitting in the house reading on a fine day like this! Go on out into the fresh air and shake your limbs.” “But mother——" “Go on out, I tell you. Can't you try to be a real boy for a change?” “But this book’s exciting.” “I'll bet. Anything in print is better than fresh air and outdoor exercise, I suppose. You're just like your—can't you ever stop reading for one instant? I declare! Onme of these days youw’ll turn into a book. . . . . Now you set that book down and go out of this house this instant.” Conrad went out to the front yard and started, with no enthusiasm, to bounce an old golf ball up and down upon the concrete walk that led from the front porch to the gate. He was thus engaged when a strange man ap- peared in the street, stopping before the gate to look for the number which wasn’t there. “Hey, sonny, is this Mrs. Burchall's house?” “Yes,” said the boy, “it is. Want to see her?” 'HE man was short, slight, and none too formidable-looking, although he was ob- viously a representative of the lower classes— possibly a tramp—Conrad was not in the least afraid of him. He had a rather friendly ex- pression, a peaceful expression, as though he bore ill-will to no one. “What's your name?” the man inquired. “My name’'s Conrad—Conrad Whidden.” Conrad wondered why the man stared at him so. “I used to know your mother,” the man explained, “before I went to sea.” “Oh, you're a sailor!” Conrad was obviously impressed. ‘“Where’ve you been?” “Oh, all over. I just came from Marseilles.” “Gosh,” said Conrad. “I'd like to go there. I've been reading about it in a buck—it’s a book . called ‘The Arrow of Gold.'” ‘The man smiled. “You were named after the man who wrote that book,” said the sailor. “I never knew that.” “No, I guess not. Your mother didn't know, either.” Just then Mrs. Burchall appeared on the front steps, attracted perhaps by the suspicious ces- sation of the sharp pops that the golf ball had been making cn the concrete walk. When she saw her former husband leaning on the gate, her first thought was this: “Well, of all things! And here I was talking about him to Adele Lent not 10 minutes ago.” Then she realized, with sudden horror, that her son was actually in conversation with his father. She wondered whether that fool Roy had said any- thing: . s “Ccnrad, you come here this instant!” Conrad ambled up the concrete walk. “How many times do I have to tell you not to talk to every strange man that comes around?” “He's a sailor, mother.” “Oh, a sailor, is he!” Somehow or other that annoyed Mrs. Burchall. “Well, you just chase yourself around to the back and don't let me catch you talking to any tramps—cr sailors, either.” Conrad cast one glance toward the man who had come from Marseilles, and then disappeared from view behind the house. Mrs. Burchall walked elegantly down to the front gate and confronted Roy Whidden. “So ycu're a sailor, are you?” she said, and