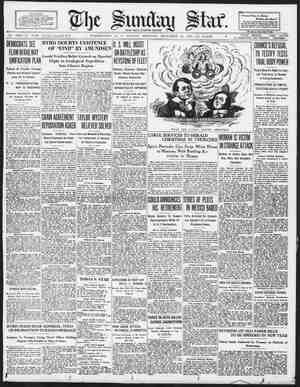

Evening Star Newspaper, December 22, 1929, Page 87

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

THE SUNDAY STAR, WASHINGTON, D. C, DECEMBER 22, very low. “From all that I know of him—why, she didn't even pretend to be sorry when they told her he had fallen from the raft. Sha2 wasn't even sorry they didn’t find his body——" “She loved him once. And, if I had lewed him, they would have gcne away together just the same,” Bertha reminded her. “No! Because then you could have kept him!” Anne cried, and stopped. “Well, I didn’t want to keep him,” said Bzrtha distinctly. *“The whole thing was a miserable failure. But it didn’t occur to me that the way to make a success was by changing the law “Why not?” cried Carl. “My dear Carl,” said Mrs. Millet, “one person or two persons cannot make a law for society— or change a law. One person or two persons can merely break it.” “But a law is made——" Carl began. “By majorities,” she said. “Where is your majority?” “All over the country!” cried Anne. “Every- where. You know how strong the feeling is——" “In that case,” said Bertha serenely, “get your majority together. Have them act together— as in any other lawmaking. Just now we are following a law made by one majority. Well, that’s our law—until another majority changes it. Dodging is no solution.” In her words there was something electric. Carl went again restlessly to the window. The storm was still driving, but now, where the Glen road opened, the light which they had seen below was nearing the summit. ““It's somebody coming here!” he exclaimed. “Anne ran to look. Bertha said indifferently: “Nobody comes here.” BUT the light was the light of a car whose laboring ascent was now audible. And it panted into Bertha’s little yard and halted, with 2 rasp of the brakes which was like a hoarse and relieved breath. "In the flash of time before the stamping steps were heard on the walk there came to Bertha a triumphant sense of these two—to neither of whom did it seem to occur to try to evade the moment by hiding. She smiled at them and went to open the door. The figure making its way through the drift in the door-yard was small and agile, but it was S0 bundled that the door was closed before Bertha recognized her. The snow-laden shawls were thrown back and there was Jane Graham. “Why, Jane!” Bertha cried. “Jane—in all this storm——" “Mother,” Anne tried to say, “what a night for you to be out——" but the words died on her lips. Mechanically taking off her wet cloak,“Jane said not a word, nor did she speak when Carl room But when Bertha sat dowh by Jane she started and drew back, looked at Bertha with a terri- ble intentness and said: “So this is the way you’ve gone about it to pay me back.” “I don't understand,” said Bertha gently. “Are you going to pretend I haven't caught you red-handed making things easy for these two?” “Mrs. Graham——" Carl burst out, but she cried: “Nothing from you!” “Mother,” Anne tried to say, “she was doing her best——" “And nothing from you!” cried her mother vehemently. “I know what I see. I found your note tonight that you thought I wouldn't see here with supplies. I guessed the rest. You two keep still. It's with this woman I've got my settling to do.” When they broke into protest Bertha said to : “Please. I want to hear——" Jane Graham turned and faced her. - “From that minute I o care. I knew he belonged to you, but I didn’t care about that, either. “Well, for a while I was giad. Anrne remem- be:sthn—shehmlmmwy. I sang all day about my work—I was happy. And then——" Bertha's level voice broke in upon hers, “Tell me something, please,” she said curious- ly. “Did you never think of me at all?” Jane looked at her indifferently. “I knew you wanted to get rid of him,” she said. “He told me that.” “If I hadn't,” Bertha persisted, “if I had loved him-—~ Jane’s eyes fell. “I loved him,” she said, “and I was a fool.” “Mother,” said Anne quietly, “if you loved each other, you would have been right. Love is the only thing in the world.” “And freedom,” Bertha put in dryly. “Yes, of course, and freedom,” Anne added hastily. PP PRT NI R s arne -0 o o e & - BRI P B He leancd ax:inst the closed door, breathing hard, like @ man spent by more thar: rv :ning. “You thought I was dead, and I guess you didn’t care.” “Freedom!” cried Jane. “That's the kind of stuff you're teaching them——" Carl sprang to his feet before her. “Mrs. Graham,” he cried, “she’s teaching us nothing of the sort. She’s been try——" But he heard Bertha's voice saying evenly: “Carl, let’s hear what Mrs. Graham has Lo say. I won't interrupt again.” “Mrs. Graham has this to say,” said Jane, “that in two years’ time I was sick to death of a gentleness which lowered the high key of the room. “It isn’t true,” he sald. “We'll tell you the whole truth——" Jane Graham swept the young people aside and got to her feet and faced Bertha. “You're right,” said Jane, “this thing is be- tween you and me. I'll tell you what I've coms to say. It’s this: I know you've got the right to hate me. But take it out some way on me. Don’t hurt these children—don't hurt Anne! And it's this: If you'll help me keep things right tortbem.lwon'tuynwordhlnyu\m'm want to do to me—not one word. Il give up the farm—I'll go off—but don’t you teach them so's harm'll come their way.” “Jane,” said Bertha, “why, Jane——" rose, trembling, stretched out her hand to the other woman, and neither of them heard the confused words of Anne and Carl trying to put their case. 4 But they all heard the voice outside which abruptly came cutting the storm and sounding within the room. And they heard the feet treading the snow of the porch. “Bertha!” they heard. “Bertha!” And they all knew whose voice it was. They stared at one another as if it were the voice of the dead, given back by the river. “It's Bart!” cried Jane terribly. Bertha Millet was moving slowly toward the door, but Jane turned like a thing struggling in a net. She saw the threshold to the dark inner room and darted toward it. Then, as the voice echoed once more—“Bertha! Bertha!>—and a sharp knock sounded, Jane cried to Anne and Carl, “Let her see him alone!” The two, in an instinctive obedience, like that of little children in a crisis, went with her, and when Bertha quietly and with an odd way of smiling thrown open the door, the room was Bart Millet entered. He must have wal Glen road, for he was caked white wi snow, and his face was white, too, like the snow that covered him. But his eyes burned, live an wild “Bertha!” he said, and stood staring at her. He leaned against the closed door, breathing hard, like a man spent by more than running He was gaunt, unshaven, but neatly dressed With a manner of strangeness, as if he had come from a long distance or a long past, he said, “You thought I was dead, and I guess you didn’t, care.” “Every one Bertha. thought you were dead,” said “Drowned, they said—" “Drowned I would have been if I hadn’t swum ] hut of a man I knew. It took him weeks to w the ice out of me—and when I found how thought to be—well, I let them y.” > 1 EEEE T the fire, nor heat. and did id shortly. “You're Jane’s husband,” she replied. At that his head went down, but he said noth- ing. Only his great hand shot out and came to its rest on her knee. For a moment she did “Bertha,” he said, “I want you back.” At this she laughed lightly and, “Will you tell that to Jane?” she asked. “To Jane—tio everybody,” he shouted, and then he caught the look in her face as she turned to the room. “Jane!” she called. From that dark room Jane Graham walked out as if from a tomb of her own. “Tell what to Jane?” she asked. He sprang up, overturning his chair, “All right,” he said ly. “I tell you both. I was a fool to ve Bertha. I love her yet.” “And what made you leave her, then?” cried Jane. Before he could speak, Bertha answered for him, for them all, quite gently. “The same thing made him leave me,” she said, “that made him leave you and that brings him back here now.” BART threw out his hands. “I wanted love,” he said simply, and looked at neither woman, but stood staring at the fire. The raw truth brought them all to quiet. It was in quict that Bertha spoke. “I wanted love, t00,” she said. And Jane said roughly: “Didn’t I want love? I was always one that wanted love as much as anybody.” In the heavy silence that settled upon the room, abruptly Jane began again to speak. “I saw you with Bertha. I thought she didn't want you. I did want you. I figured it out that it wasn't right for you two to stay together, if you didn’t love each other.” “Wait!” Bertha's voice came doggedly. *“I saw that you liked him.. I wanted to be free of him. Time after time I threw you two together.” Bart Millet laughed. “I saw you both maneuvering,” he said, “Jane 10 get me and Bertha to get rid of me. I was mad because you didn't love me and glad you did. I wanted love—but I don’t know whether T loved either of you, and I know now that neither of you loved me.” Theeysonhuethreetumedbackulongme dark paths down which they had passed, alon: or together, looking for love. And the three stood there empty. The silence continued and seemed about to snap when Bart Millet stirred and shifted. “I guess I'll go now,” said he some- what foolishly. Neither woman spoke. He got into his coat, the water and got ashore downstream by turned up its collar, hodded with stiff and ale most ludicrous formality and left. Bertha whirled. “Oh, Anne!” she called. “Oh, Carl!” Against the dark doorway Anne and Carl were like two spirits, “It was most fearful eavesdropping——" Anne began, but Bertha-cried: x “Promise each other—here and now—that no such ugliness as this shall ever touch either one of you. Promise!” Carl stretched out his hand. “Why, of course,” he said proudly, “I can promise to love and ‘cherish Anne all her life, so that nothing like this shall ever come near her.” “Oh. I can promise,” sald Anne gravely. “But you two poor——" “Wait,” said Bertha. “You two are promising to love each other all your lives!” “Why, yes, yes!” Anne cried. “Carl is not like that man—Carl and I—" “Anne and I——" began Carl. “That’s all that marriage is,” said Bertha. “Are you really afraid to say such things before your friends and the law?” E In the silence that fell Bertha's words came unforgettabily: “Our failure did not come from being married too much,” she said; “it came from not being married enough.” Jane Graham's voice came shrilly: “But I thought you were arguing them out of marriage, Bertha Millet!” “Even if that had been true,” said Bertha gently, “I couldn’t have borne it to bring any more suffering on you.” At this Jane Graham covered her face with her hands. She did not weep—it was as if she remembered how no longer; but her hands upon her face were of sovereign eloquence—toil-worn, tired hands that had made nothing of life and had from life but one gift—Anne. Anne looked at Carl and their eyes spoke to each other. “Mrs. Millet,” Anne said only, “if we’'re married on Christmas day, will you come down to the wedding?” Bertha's eyes were on the window, and the storm having lessened a little, she could see again the light left burning in Jane's house. “I'll come,” she said. Jane’s harsh voice steadied them all. “It's your own house,” she said to Bertha, “and your own things. You'd better stay, and Il go ” ¥ “Isn’t there room enough in that house for both of us?” said Bertha. “Anyway, we can spend Christmas there, and then we'll see——* The word Christmas hung in the air like a star. Co-operatives in Switzerland -OPERATIVE assoclations of farmers, . which are just nicely getting into their stride in this country, are an old story to the Swiss, who have joined various co-operative or- ganizations to the extent of about nine members per farm in their country.. Perhaps the nature of the farms in Switzerland, where a farmer may own a number of sections of land, scat- tered about between holdings of various neigh- bors, has a lot to do with it. In reporting on the results of investigations carried on in the republic, Asher Hobson, a col- laborafor of the Department of Agriculture, says that out of a total population of about 4,000,000 people in Switzerland, about one-fourth depend upon agriculture for a livelihood. Production and co-operative marketing are more highly de- veloped in that country than in any other coun- try in Europe, except, perhaps, Denmark. In 1920 there were 10,942 local co-operatives with 897,082 members, or an average of nine co-operative memberships for every farm in the country. A single individual may be enrolled in more than one local co-operative, a local co- operative may be affiliated with more than one central organization, and more than one mem- ber of a farm household may be a member of one or more co-operatives. Co-operation and dairying are almost synony- mous in Switserland. In 1920 there were 3,519 local dairy co-operatives, with 102,659 members, These locals are united into a number of differ- ent types of federations, the Central Union of Swiss Milk Producers being the hub of the or- ganized dairy movement. This union has 25 member federations, repre- senting 3,392 local societies, with 99,059 mem- bers. It controlled the product of 534,852 cows of the total cow population of 810,000 in 1924, Hence the production of 66 per cent of all the m-hthnteountryhmmnedbyoncgu- tral federation. 5 Switzerland produces about three-fourths of its food supply, but only one-sixth of its wheat requirement. The value of agricultural imports - is about four times that of exports. Two-thirds of the farm receipts of the country come from dairying, cattle feeding and hog raising. Animal products of high quality are exported. “Perhaps the greatest single handicap to’ Swiss agriculture,” Mr. Hobson declares, “is that many of the farms are divided into a num- ber of separated strips. There is great loss of time in going from one parcel of land to an- otba.mumuchnm:nyo(theplecubelong- ing to a single farm may be one, two or three miles away. “Labor and interest on land and capital ave the lergest items of cost of farm operation. In- terest at 5 per cent on capital investment ae- counted for approximately one-fourth of total farm costs in 1924. Labor represented 42 per cent. Approximately $50 worth of labor was applied to each acre of land in farms in 1924, Farm labor that is hired on a permanent basis, such as dairy hands and horsemen, receives. about $4.25 a week with board. Harvest help hired by the day is paid around $1.20. Day labor during other seasons of the year may be had for 90 cents a day.”