Evening Star Newspaper, January 4, 1935, Page 5

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

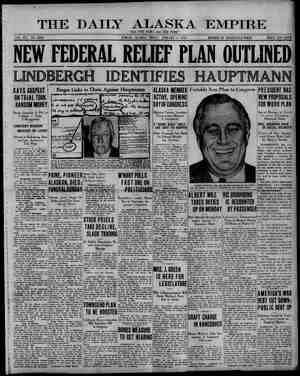

TENSE STORY TOLD BY MRS. LINDBERGH Woollcott Sees Hauptmann’s . Egotism as Motive for Crime Writer Praises Mother for Calmness on Relates How She Played| Stand—Believes Accused Man Resent- With Child During Minutes Before Kidnaping. ful of Lindbergh’s Popularity. BY ALEXANDER WOOLLCOTT. — By the Associated Press. FLEMINGTON, N. , January 4 (N.AN.A.).—In a hush that stilled the FLEMINGTON, N. J., January 4— For 45 dramatic minutes here yester- day, Anne Morrow Lindbergh, the slight, brown-haired mother, related what she knew of the day and nmhtl of March 1, 1932, when baby Charles Augustus Lindbergh was stolen from | the Sourland Mountains home of hls[ parents. ! Once her eyes gleamed as though with tears, but she did not lose her composure as, in low, clear tones, she said simply: “I looked hastily at the bed—and found it to be empty.” Mrs. Lindbergh, pale and dressed simply in black, faced Hauptmann, but did not look at him as the pris- oner shifted occasionally in his chair. The defense did not cross-examine her. Smiles Occasionally. ‘What mental anguish she conceiv- ably was enduring she concealed. In her manner at times was just a trace of restraint. She smiled, occasion- ally bit her lower lip, and for the most part sat erect in the old wooden chair, her legs crossed, her elbows resting on the arms, her hands lying in her lap. l;he described her son, speaking in tender tones. She looked at an en- larged photograph of him, showing him with blond, curly hair, looking up in baby surprise. She identified photographs of the nursery at the Hopewell house, of the crib and other furnishings, and de- scribed them in answer to questions. And even when Attorney General David T. Wilentz, proceeding in his questioning with the utmost care, showed her the baby's sleeping suit, his thumbguard, his tiny shirt made of flannel to protect his chest against the cold, and a second shirt he wore, she kept herself in check. Put Sleeping Suit on Child. Of the sleeping suit she said: “I put it on my child.” Col. Lindbergh half rose from his geat as his wife sat in the witness chair and _Wilentz —momentarily blocked his view. The preliminary questions were brief. Wilentz plunged at once into the happenings of March 1. “Who was at the house that day?” court house at Flemington so that every person in it, from the mild old judge to the most tremulous attendant sob sister, seemed suddenly to have stopped breathing, Anne Lindbergh took the stand in the trial of this young German carpenter from the Bronx for the murder of her little son. As a reporter of long standing, I have at- | ¢h, tended many a murder trial in my time, but never in any of them have I known a moment so intolerably painful in its suspense and its significance as that in which this gentle and gallant woman, with a grace of spirit which no dispatch from Flemington can hope ade- quately to repori, faced her ordeal yesterday afternoon. Deferentially, the counsel for the State led her through every hour of that fateful 1st of March three years ago. We in the listen- ing court room heard about the walk she took in the afternoon and the merry pebbles with which she pelted the nursery window to catch her small son’s attention when she came home in the twilight. scamper ‘We heard all about his last to the kitchen after his bath and the last glimpse of him tucked in his crib. Handles Baby’s Clothes. ‘The very things he was wearing when last she ALEXANDER WOOLLCOTT. saw him had to be entered as exhibits for the jury—the sleeping suit and the thumb protec- tors and those little shirts, one woolen and one a flannel shirt they had cut | out and stitched for him there in the nursery. It was her job to take them once more in her hands, with the whole world watching, and testify about them with such steadiness of voice as she could muster. Some of us could look no more, and, turning elsewhere for relief, found ourselves staring fascinated at Hauptmann himself. In that impassive and haughty face I seemed to see for the first time the glimmer of something like an expression. If I read it aright, it was an expression of faint resent- ment that any one other than himself should even for a moment be the center of attention. By all that she was and all she had experienced, Mrs. Lindbergh brought to the proceedings in this Jersey court room a final dignity which all the yammer of the radio, all the hullabaloo of the tabloids and all the turmoil of the frustrated sightseers can do nothing to lessen. Detective Story Recalled. By their unflinching part in this prosecution, the Lindberghs are serv- ing as best they can all the nurseries in America and once more deserve well of the Republic. A crime which communities is here running its course by supreme self-control. In one of the Sherlock Holmes stories, that famous detective so far unbent as to call Scotland Yard's at- tention to the curious incident of the dog in the night. But, they protested, the dog did nothing in the night. “Yes,” said Mr. Holmes, “that was the curious incident I referred to.” Today brought Hauptmann and the Lindberghs together under the same roof for the first time—or for the first time in nearly three years. Today Mrs. Lindbergh saw for the first time “I was there myself and my son, Charles A. Lindbergh. jr.; Mrs. Elsie Wheatley, her husband, Oliver Whea ley, and later in the day Betty Gow.” “So that the household” Wilentz said, “on that date consisted of your- self and also Col. Lindbergh in the evening?” “In the evening,” Mrs. Lindbergh repeated, nodding her head as she in- variably did in giving affirmative re- lies. = The birthday of the child, June 22, 1930, and his age, 20 months, were es- tablished. Mrs. tindbergh said she went for a short walk alone after Betty Gow, called from Englewood to care for the baby, arrived. The walk lasted per- haps 15 minutes, “perhaps half an hour.” Tells of Playing With Baby. “Now, during that day,” Wilentz went on, “had you played with Charles, §r.; spent much time with him?” “I had been with him all morning, I put him to sleep for his nap about 1; and in the afternoon I played with him after he awoke from his nap.” Mrs. Lindbergh smiled. the man whom she must believe mur- dered her little boy. As he came to his seat after the noon recess, he had to pass so close to her that she could have put out her hand and touched him. No word was said. No gesture was made. The leading figures of this tragedy were assembled within a small railed space and nothing happened. 1t is of the very essence of the drama of this case that nothing happened. Doubts Wilentz Statement. Mr. Wilentz, the lawyer from Perth Amboy, who, as attorney general of the State, is conducting this prosecu- tion, made the opening address to the jury. He is quiet, personable and Levantine of aspect, and his speech was able, discreet and effective. But in it he said one thing of which I doubt the truth. In his eagerness to suggest that the murder of the Lindbergh baby was a crime dictated by greed, he said: “This fellow had nothing against Charles Lindbergh.” When at long last the full story of this monstrous crime becomes a matter of record, as “After I returned from my walk I walked around from the driveway under his window and tried to look for him,” she continued. “I attracted the attention of Miss Betty Gow (the baby's nurse) by throwing a pebble up to the window, and she then held the baby up to the window to let him see me.” She smiled again, quietly, and her eyes were faintly moist. Wilentz brought out, through questions, the window Mrs. Lindbergh meant—the nursery window, out of which the baby ‘was stolen that night. At this point she rose from the may well happen before this year has runy its course, I think it will be shown that that Hopewell nursery was rifled by one who hated the world's hero with all the insane jeal- ousy of which an egomaniac is ca- pable. This was no such random blow as was struck in the Leopold- Loeb case, and in that lies the only essential difference between the two crimes. Otherwise, they march side by side. Jury Proves Surprise. Those prophets who had filled the air with sagacious predictions that it would take weeks to select a jury chair, took from Wilentz a long|were thrown into confusion when, less pointer, and standing before the|than an hour after the court was court, slim and girlish, directed the | called to order this morning, a gray- pointer to the floor plans of the Hope- | haired, unemployed bookkeeper and a well house, pinned on the wall. Leaves Footprints Under Window. Wilentz, by further questioning, es- tablished that Mrs. Lindbergh had left footprints in the muddy earth under the window. This was at 3:30 o'clock in the afternoon. “After my walk,” Mrs. Lindbergh continued, “I went up into the baby's bed room where I found Miss Betty Gow and Mrs. Wheatley. Then I went down again, I think, into the sitting room. About 5 o'clock I had the baby down in the sitting room playing with me. He left me to run into the kitchen. After that I did not see him until I went up into the nursery about 6:15 or after, when he had almost finished his supper. “From that time on for about an hour or a little more than that, I was with the baby, helping to dress him and prepare him for bed.” Wilentz turned to the child’s nature and appearance. Declared fo Be Normal. Mrs. Lindbergh smiled, leaned for- ‘ward, and said: “He was perfectly normal.” “Healthy?” “He was very healthy,” Mrs. Lind- bergh answered. Again she smiled and nodded, then suddenly checked the smile and bit her lip. Col. Lind- bergh watched her intently. “Playful?” Wilentz asked in a mat- ter of fact manner. “He was a great deal better than he had been the preceding two or three days when he had a cold, a slight cold.” “Was he able to talk yet?” “He talked,” Mrs. Lindbergh said. ‘Wilentz wanted to know to what extent. little, gnarled, weather-beaten old carpenter were mysteriously found acceptable to counsel on both sides. Thus was the jury box filled on the morning of the second day. In advance it had seemed reason- able to fear it might be necessary to draft the entire citizenry of Hunter- don County in the quest for 12 adults who had neither discussed the case nor formed any opinion about it. One would expect to find such satis- carried it to Mrs. Lindbergh, asked her if that was the shirt. She touched it, nodded, said “Yes.” There was an audible quickening of breath among the spectators, but Mrs. Lindbergh never flinched. The shirt was offered in evidence. Other garments followed—a small, sleeveless wool shirt, cut low in front and back; the sleeping suit and the thumbguard. The suit was clean. Before it was sent to the Lindberghs by the kidnaper it had been washed. ‘When she came to the thumbguard, a wire device designed to stop the habit of thumb-sucking, she explained how it had been fastened with tape around the wrist of the baby. She encircled her left wrist with her fingers to show more graphically just how the guard was attached to the wrist on the outside of the suit “so it would not cut his wrists.” ‘Wilentz then elicited the facts about Col. Lindbergh’s arrival from New York, about their dinner together and Mrs. Lindbergh’s preparations to re- tire. Child Discovered Missing. “s » » After I had taken my bath Miss Betty Gow came in to see me through the hall door and asked if I “I don’t remember any particularhad the baby and, hearing that I did conversation on that afternoon,” she answered. “Of course, he called all the members of the household by name, and he played about the floor with me in the living room.” Gives Color of Baby's Hair. Wilentz asked the color of the baby’s hair. “It was——" Mrs. Lindbergh hesi- tated, “light golden.” Wilentz showed her the photograph. She looked at it with no outward sign of emotion, and it was offered in_evidence. Wilentz led her, bit by bit, with neatly framed questions, to the de- scription of the nursery, the location of the room. The baby was ‘put to bed about 7:30, Mrs. Lindbergh said. Miss Gow and Mrs. Lindbergh dressed him for bed. “He had next to his skin a home- made flannel shirt which Miss Gow cut out and sewed that night out of a flannel petticoat which I had since the child was an. infant.” From the prosecution table Wilentz picked up & soiled little shirt. He 2 not, asked me if my husband had the baby, and I sent her downstairs: “I then went into the baby’s room through the connecting passage. This was after 10 o'clock, shortly after 10 o'clock. I went into the baby’s room through the conecting passage, looked hastily at the bed, found it to be empty, came back into my roem, vagu-e I met my husband and Miss “My husband went into the closet to take out a rifie and we all three went into the baby’s bed room and searched it. I was still in the baby's bed room when Mrs. Wheatley came upstairs, and I went with her back into my own bed room and got dr 3 and we started to search the house.” The rest of her story was quickly told—how Mrs. Lindbergh and her husband realized their child had been kidnaped and made a radio appeal to the kidnapers to take care of the baby, who she never again saw. Mrs. Lindbergh probably will nat be recalled in future trial mnum&’:n- lentz declared, because nothing is “in sight” to warrant further testi- mony from her. [ would have meant a lynching in some in an orderly and patient trial marked factory aloofness only among con- genital idiots or among those who had spent the last few months in the kind of withdrawal from this world usually achieved only by lamas in Thibet. But as it worked out, nearly every member of the panel seemed eager to serve on the jury and was unblushingly willing to put his or her hand on the court Bible and blandly deny ever having given the case a thought. Thus in our time in New J:rfily is justice served quickly—if al . (Copyright. 1935, by North American Newspaper Alliance, Inc.) Lindbergh Testimony At Yesterday’s Session (Continued Byom Fourth Page.) this, but, if the court please, we would like to know when it was taken. Mr. Wilentz—Yes, sir. Mr. Reilly—How it was taken and by whom it was taken. Mr. Wilentz—My information is that—well, let me offer it for identifi- cation. Mr. Reilly—For identification, yes, follow it up tomorrow. (The photograph was marked State exhibit S-6 for identification.) Q. Well, at any rate, Colonel, there was the note and the ladder, impres- sions in the ground that you speak about, the child gone, police officers coming—I suppose the press soon came, too? A. Yes. Q. And about how many, would you say, were represented there in Hope- well that night before daybreak? A. I don't know, I imagine several hundred. Q. Several hundred. So that, I take it, between the press and the police— and there were police of many organi- zations, weren't there? A. There were. Q. I take it that there was consid- erable confusion and walking in and about the premises, right? A. Well, there was, the greatest con- fusion was before all of the press ar- rived and while the press was there, there was a great deal of walking around outside of the house by the press which was absolutely out of con= trol as far as the vicinity was con- cerned, Q. I suppose that included the taking of pictures and flashlights and things of that kind? A. Yes, and walking around the house on the loose ground there. Assisted Officers. Q. And during all that time you were doing what, Colonel? A. Dur- ing the first period I was around the house trying sto familiarize the of- ficials with what had happened. Q. And go ahead, Colonel. A. Later in the evening and during the early hours of the morning I was out on different parts, different places in the vicinity of the house, with the group of police officials, visiting other houses. Q. I want to go back for a min- ute, please—it is quite disconnected, possibly, but I want to get back to the time in the house, and particu- larly when you were in the living room. As I remember it, the living room opens into the hallway, isn’t that s0? A. Yes, yes, in addition to other doors. Q. But it does open into the hall- way. A. With a double door. Q. With a double door. And, there are two staircases, one leading to the right and one leading to the left, isn't that s0? A. One staircase from the living room. Q. One staircase from the living room? A. From the living room. The other stair is in the back of the house. Q. In the back of the house? Well, now, the staircase leading from the living room —could you see that? You couldn’t see it unless the door was open, could you? A. No. Q. Was the door open that night when you came from dinner and walked into that living room, for 15 minutes or so? A. Yes, sir; the doors ‘were open that evening. Q. Did anybody—I will withdraw that. They were open that evening as I understand it? A. Yes. Q. Were the doors open to the library from the living room? A. Yes. Tells of Wheatley’s Search. Q. We will get back, then, again to the scene in the home, the con- fusion. Mrs. Lindbergh, I take it, remained in the house? A. I believe 80, yes. Q. Did you not also have Mr. Wheatley drive the car along the premises, playing his lights on the highway or on the road for a part of the way? A. Mr. Wheatley went out- side. At the moment I don’t recall just what his actions were. He went outside and was searching outside for & time. Q. Al right, sir. Having received this first note, did you receive an- other? A. By yes. Q To you directly? A. The next FLYER IDENTIFIES HAUPTMANN VOIGE Tells of Ransem Payment as Cross-Examination Begins. (Continued From First Page.) for the boat that you hoped had your son in t?” “That is correct.” “Your search, of course, was in vain " Wilentz prompted. Lindbergh replied simply. 'You returned then where?” - “I believe we returned to a field, a landing field near Hempstead, Long Island, called the Aviation Country Club.” “Did you make another effort in a plane to locate the boat that was sup- posed to be the one that you were looking for?” “I did later.” “When? The same day?” 'No, it was a day or two forward.” “I see, and who went up with you that time?” “At the moment, I don’t recall who was in that plane.” Search Was in Vain. He piloted again, he said, and was up in the air for several hours. “And again that search was in vain?” “Yes.” ‘Then he landed at Tzterboro Air- port in New Jersey, he said, and drove on to his home in Hopewell—“that was in April, during the early part.” ‘The flyer's full testimony on the matter of hearing what he alleged was Hauptmann’s voice, was as follows: Q. On the night of April 2, 1932, one was addressed to me at our home in East Amwell Township. Q. Note No. 2? A. Yes. Mr. Wilentz—May I have that note, please. Mr. Wilentz—Has your honor any objection to indioating to counsel what time your honor expects adjourn, so I can regulate my exam- ination accordingly? The Court—If it would suit the convenience of counsel, I would be willing to adjourn quite speedily. think the room is quite warm. Does counsel prefer it? Mr. Wilentz—I would like to get one breath of fresh air within the next half hour, but if there isn’t any objec- tion, I should like to just finish with this note and then continué in the morning, if it meets with your honor’s convenience. ‘The court—That, I think, will be satisfactory. By Mr. Wilentz: Q. Will you take a look at that envelope, please, Col. Lindbergh, and this note and see if that isn't the note which you received second? A. This is the envelope which contained the second note and this is the second note contained in the envelope. There are some initials on there that have been put on since. Mr, Wilentz—All right, I will de- scribe them. I will offer them in evidence. I am going to ask the court, please, if you don’t mind—I don’t want to be offensive either to the court or counsel or the press, but I would ap- preciate it, even though this is the last minute of this testimony, if the people in the room would remain here until we get through, so there won't be this apparent confusion that we are meeting with back there. The court—VYes, that is an entirely proper request. It won't be long now before we take an adjournment and there is no reason in the wide world why everybody who is in the court room now should not remain here un- til the court has adjourned. The people will observe that order and keep quiet so we can all hear. (The envelope referred to above was received in evidence and marked State exhibit S-19.) i+ (The note referred to was received |in evidence and marked State's ex- hibit S-20.) Mr. Wilentz—Exhibit §-19, then, is an envelope addressed to Mr. Colonel Lindbergh, Hopewell, N. J.. and note No. 2—we will refer to this as exhibit 8-20— The court—That has been offered in evidence. Mr. Wilentz—And marked. The Court—No objection. It will be admitted. Note Read. Mr. Wilentz—Exhibit 8-20 reads: Dear sir: We have warned you e—"“to make anyding”— -g—“public or notify the police. Now you have to take the consequences. This means we will hold the baby until everything is quiet. We can nof e—"make any appointment just now. We know very well what it means to us. It is really necessary to make a world affair out of this or to get your baby back as soon as possible. To settle this affair in a quiet way will better for both. Don’t be afraid about the baby. The lady taking care of it day and night. He also will feed him according to the diet. Singture on all letters with an arrow pointing to the circles and the red dot and holes. We are interested to send him back in gut"—g-u-t— “ouer”—o-u-e-r—“ransome was made up for 50,000"—with the dollar mark afterwards— but now we have to take another person to it and probable have to keep the baby for a longer time as we expected.” I want you to watch that point. “So the amount will be 70,000"—with & dollar mark after it—*20,000 in 508 bills, 25,000 in 20$ bills, 15,000 in 10§ bills, 10,000 in 58 bills. Don't mark any bills or take them from one serial number. We will inform you later " — w-e-r-e — “to deliver the ‘They—t-h-e—the money— m-o-n-y—"“but we will note"—n-o-t-e —*“do so until the police is out of this case and the papers’—p-a-p-e-r-s— “are quiet. The kidnaping was pre- pared for weeks so we are prepared for everything.” Mr. Wilentz—May we then at this time adjourn until tomorrow morning? The court—The court will take a recess, but I will ask everybody to re- main quiet, standing or sitting where they are, until the jury has retired. The jury may now retire. Has the Jjury retired? Court Crier Hann—The jury has gone out. ‘The court—The prisoner is remand- ed in the custody of the sheriff. He may retire, (Whereupon, the court adjourned until tomorrow morning, January 4, 1935, at 10 am.) $5,000 PAID BY BANK of the bank was voiced at & meeting of directors, when you were -in the vicinity of St. Raymond’s Cemetery and prior to de- livering the money to Dr. Condon and you heard a voice hollering, “Hey, doctor,” in some foréign voice, I think as you referred to it—since that time have you heard the same voice? A. Yes, I have. Q. Whose voice was it, colonel, that you heard in the vicinity of St. Ray- mond’s Cemetery that night say, “Hey, doctor?” A. That was Haupimann's voice. Q. You heard it a second time where? A. At District Attorney Foley's of- fice in New York, in the Bronx. After telling that the serial num- bers of the ransom bills were re- corded at his request, Lindbergh re- well; and did -you visit's morgue in Trenton?” . “;GOn the following- day I did,” he i By the way,” Wilentz went on, “in March, 1932, when was the last time you saw Charles A. Lindbergh, jr.?” “On' the Sundsy evening “And from that time on did you ever see that child alive again?” “I did’ not.” “Did you see the child at all again?” “I saw the child’s body.” “When?” “On the 13th of May, 1932.” “Sometime slightly after midnight of May 12th?” “Yes” = %’M it was your child?” “And you ordered the body cre- mated, as I understand it?” “Yes Right after this Wilentz said: “So that you did not get your money g |.back and did not get your child?” “I did not.” Lindbergh said. Col. Lindbergh squared his shoulders as he prepared for Defense Counsel Reilly's first questions of cress-ex- amination. ‘There appeared scant possibility that Betty Gow, the dark Scotch nurse of the slain child, would testify today. She was to have followed Mrs. Lindbergh on the stand yesterday, but she was so distraught after hearing her mistress’ testimony that she was unable to take the stand. Reilly declined to cross-examine Mrs. Lindbergh, telling the court: “The defense feels that the grief of Mrs. Lindbergh requires no cross- examination.” Later, he said, “as & witness she told a splendid, sympathetic story. But it was not evidentiary. As a woman, she is most charming aad admirable.” When she stepped down from thé stand and the State deemed Miss Gow too shaken to follow her, Lindbergh was sworn out of turn. now buys Bond overcoats regularly up to *25.00 it covers our entire stock of 2 trouser suits and overcoats. First time we’ve reduced our Rochester-tailored clothes. Price-cuts go the limit! You know exactly how much you save — without guess- ing —for you've seen ali these suits and overcoats at their regular prices. You can “charge it” with our Ten Payment Plan—at no extra cost to you. No eharge for alterations : CLOTHES ‘ 1335 F N.W. now buys Bond 2 trouser suits regularly up to *30 VA now buys our Rochester-tailored clothes formerly up to *35 The sale price of every suit includes 2 trousers