Evening Star Newspaper, November 30, 1930, Page 99

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

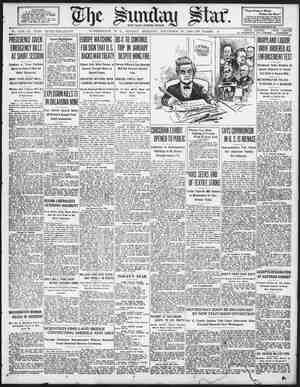

THE SUNDAY STAR, WASHINGTON, D. C, NOVEMBER 30, 1930. 11 ‘Russia’s Effort to Get Along Without HOME COOKING | How the Ambitious Soviet Schemers Plan to Banish Kitchen Drudgery for Women, Within Five Years, by Subsiituting Food Chemists Who Will Do All the Meal-Getting for Entire City and Rural Communi« ties. N Soviet Russia “kitchen factories”—that is, kitchens run on a factory scale—are expected within five years to render / home cooking obsolete. They will at least destroy the power of the notorious *“primus,” the one-burner oil stove which has furnished material for unending ridicule on the part of Soviet and foreign critics. To American housewives with their roomy, modern kitchens, socialized cooking may not seem very desirable, although American fam- flies “eat out” much more than formerly. But in Russia’s crowded cities, whole families five in one or two rooms where they prepare their meals, or several families use one. com- munity kitchen. If a dozen families occupy one filat, then a dozen one-burner kerosene stoves stand on the rarely-used brick oven in the community kitchen. Housewives and maids prepare the family meals while the vicious lit- tle stoves sputter and smoke; if it is a more modern kitchen, they stand in line waiting for places on the four-burner gas range. Perhaps each of the women has already stood in other lines for hours that day in order to buy the products necessary for the meal. Life in Moscow is just one line—or queue— after another—queues to board a street car, and to buy galoshes, butter and vodka, and queues at the registry offices to get married and divorced. I have noticed that a con- tented expression settles down on the face of a Muscovite when he takes his place in line, as if to say: “Well, here I am, waiting along with the rest; I don't need to worry—my turn will come some time!" NO’I'HDIG will have a more practical effect in dissolving queues than public dining rooms, since they will eliminate the necessity of individual marketing. ‘The makeshift of communal life to be found in the usual community kitchen has been created not so much as a matter of principle as by the lack of housing space and equipment; there is the same grim necessity, perhaps, be- hind the avowed principle of sex equality and economic independence for women. Women are needed to help carry out the rapid industrialization of the country, and leaders say that women cannot do justice to their “social work” if they have the double burden at home. Hence the government has from the first been bending its efforts toward the abolition of private cooking and house- keeping, by opening public dining rooms for workers, and day nurseries for their children. And the latest and most scientific result is the kitchen factory. — ‘The People’s Commissariat of Food, known cryplically as “Narpeet,” has an important role, to play in the execution of the stupendous five- year plan by which the Soviet government hopes to industrialize Russia by 1934. “Nar- peet” has for this purpose a budget of 1,700, 000,000 rubles—almost a billion dollars. At the end of the five-year period, “Narpeet” is pledged to feed daily 75 per cent of the workers and 50 per cent of their families in public eating places, preparing a total of 50,000,000 a day! ‘These ambitious builders of a new society @admit that the greatest drawback to the carry- ing out of their program, next to the shortage of food, is the shortage of trained cooks; they have only 6,000 at present. But schools have already been opened to train “culinary en- Dm!:C'!ORs of kitchen factories are the instructors. The sum allotted to the training of cooks is quoted at 20,000,000 rubles, and already more than 20,000 persons are en- solled in the schools of “Narpeet.” “In order to prepare good soup for our din- fng rooms,” declared one instructor, “it is necessary to be active in our social life. A ©ook who is indifferent to our construction pro- gram can never feed the workers well.” 80 now everywhere are labor union schools for training cooks, all no doubt first examined for their “political reliability,” and their sym- pathy for and participation in the new life. Today, giant kitchen factories are springing up all over the vast Soviet land. In far-away mountain villages, in the agri- eultural collectives, and in every city—in ©Odessa, In Kiev, fn Nizhni Novgorod on the A satire on the old Russian housewife with her “primus” or oil stove. Volga, in Novo Sibirsk, capital of S!beria, and in Minsk a factory prcducing 24,000 me>ls a day. Perhaps in the new scientific kitchens men and women will take pride in being cooks, a profession regarded as somewhat menial, slav- ish and poorly paid. I recall that in our in- dustrial colony Kuzbas in Siberia, our most difficult labor problem was providing cooks for the community kitchen; one after another they would desert the kitchen and go to work in the mines, preferring to dig coal rather than drudge in the kitchen. . In “Crime and Punishment” Dostsevsky quotes one of his chiracters as advancing a clever argument in a debate cn Socialism. “Well, all right, everything will be lovely, every man will Bedlam! A Russian housewife pictured in one of the old-fashioned apartment kitchens which provided such poor food through such terrible drudgery and squalor. BUT the Russian Communist of today says: “Dcstoevsky’s hero knew nothing about plumbing; now the wide masses of the popula- tion, even in our country, are familiar with it; Young patrons of the first children’s dining room in Moscow. Paid supervisors see to it that they eat their carrots and most of them gain in weight and health without parental supervision. be lifted to the level of a half god—neverthe- less, who will clean the outhouses?” And the Russian Socialist of that day replied uncon- vincingly: “I'll do it, even if I am of noble birth!” now we are arranging things so that there aren’t any outhouses.” The conrlusion is that the machine age is fast eliminating disagreeable labor and auto- matically solving a problem which has baffled Cooking hall of the first factory kitchen in Leningrad. It is fully equipped with the newest electrical cookers and is kepg spotlessly clean by cooks who call themselves chemical engineers. This is an artist’s poster aimed at advancing the cause of the new scientific community “factory kitchens.” social reformers of every generation—the prob- lem of who is to do the dirty work. There should be note to do. The first experimental station of the Food Commissariat was opened in Mosccw early this year. When you visit the station, you see a man in a white apron and cap who is standing by a large stcam kettle, “Comrade cook—" you begin by way of greeting, if you are a loyal Sovietist. He smiles. “I am not a cook, I am a chem- ical engineer. You will see, soon only chem- ists will feed the people!” Food is cooked in steam. The experimental station has prepared a standard meal, scien- tifically cooked and containing the necessary calories and other properiies. Under its di- rection, the culinary Soviet which meets once a week tests the quality of dinners served in public dining rooms and restaurants. Notices are served on those eating places whose meals fall below the standard—and there are many of them. “We shall reach out to the collective farms, to the villages and towns, and millions will leave their ancient hearthstones and individual primus and live a more healthy, happy life,” the chemical engineer declares enthusiastically. As a direct ocutcome of the research work done by the experimental stations, the first kitchen factory was opened in Leningrad, in a great new building whose kitchens are fully equipped with the most modern electric ma- chinery for pceling vegetables, grinding meat and washing dishes. In the cooking hall stands a row of her- metically sealed, shining boilers; it is a spot- less, roomy place as unlike the smelly, dirty, crowded Russian “community kitchen” as sun- light to darkness. The menu is posted on the street below: “Bouillon, 20 kope:ks; ground beef, 25 kopecks; baked duck, 30 kopecks; chicken in sour cream, 45 kopecks.” TBE cashier’s desk, resembling the ticket of- fice of a moving picture theater, is in the corridor; heré patrons select and pay for their dishes, which are numbered on the printed menu, and with their checks they enter the buffet, or main dining room. The buffet is simply a kind of great lunch counter, but the dining room is a great hall bandsomely decorated, spacious and quiet. No smoking whatever is allowed here—there is a smoking room elsewhere in the building, and a long terrace and reading room besides. Hot water is on tap in the wash rooms. In the dining hall you see many families, and the diners are in various kinds of attire— workers in blue blouses, greasy trousers and heavy boots, women in shawls, office employes and “responsible workers” more smartly dressed —and all wearing a pleased and satisfied ex- pression. For while to you this dining room does not appear so wonderful, to them after the dirt, confusion and congestion and bad food of the usual public eating place and of their own homes, it is a Utopia such as Edward Bellamy pictured in his “Looking Backward” half a century ago. HOW are the children, the most important consideration in any social program, pro- vided for in this widespread sockdization of the kitchen? The answer is simple; they have their own dining rooms!