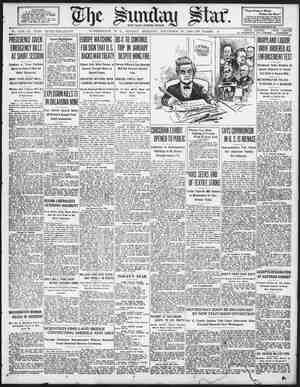

Evening Star Newspaper, November 30, 1930, Page 98

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

THE SUNDAY STAR, WASHINGTON, D. C, NOVEMBER 30, 1930. Under the Oleander By M. A. de Ford. A Powerful Story of the Jea]ousy Between Brothers and a Blind Man’s Revenge After Persecution. Tllustrations by George Clark. VEN when I still had my sight, the big oleander tree meant something very special to me. Afterwards. of course, it became still more impor- tant, a sort of conter of my being. Now that it is gone, and Gilbert, and in a sense Anne, and soon I shall be gone myself, it pleases me to trace the impalpable thread that bound us all together. When I was sti'l a small child, and Gilbert was a baby, while our mother and father were still alive, the oleander was already so large that by stretching my arm through my bed room window I could touch the uppermost cool pink blossoms. I believe that in the East and in Europe the olzan‘er is only a small shrub, but here in California ia the warm, protected valleys it grows to tree-like size. This one had double pink flowers, peeping out from among the thick, flossy leaves. ¢ reinember its appzarance so w2ll—just as I re- member its faint, troubling perfume. People with an insensitive sense of smell used to say it had no perfume at all, but I knew better. My mother planted it when she was first married, and Gilbert and I played under it all through our childhood. We used to prick the leaves with a pin to let out the milky sap, and pretend to use them as fodder for the animals of our Noah's Ark. Gilbert broke most of the animals in time, as he did all our toys, par- ticularly mine. I can still hear my mother saying “Let baby brother have it; he’s smaller than you.” WHEN I was about 18 and thought I was going to be a poet many is the night I spent sitting by the open window in Summer, instead of in bed where I belonged, breathing with the faint brezze in the oleander, sometimes stroking the smooth leaves and silky blossoms that waved just outside the sill. Then Gilbert and I went to the university, and after I met Anne and almost immediately became so wholly and completely hers I remem- ber taking her to the ranch over the Christmas holidays to meet my parents, and I remember, oo, standing with her under the oleander tree and thinking how its flowers were almost exactly the faint pink of her cheeks. It was raining a little, a soft,” pleasant rain, and Gilbert came out of the house rather abruptly and took Anne by the arm and hurried her onto the dry porch. It was in our last year at college that the accident happened. You see, though Gilbert was younger than I, our parents liked us always to be together, and so I did not go to the univer- sity until he was ready. So we were nearly always in the same classes, and we stood side by side in the chemistry laboratory. Gilbert was majoring in chemistry; I cannot say I had a sclentific mind, and as a selfish personal mat- ter I should much rather have specialized in languages; but father preferred us to take the same course, 50, of course, we did. Gilbert, was much better than I in chemistry —in fact, I imagine I gained the name of being a good deal of a dullard, for I couldn’t seem to get interested in the things I was studying, and I did too much irrelevant reading on the side. And, of course, a great deal of my time and thought went to Anne. I really think if that dreadful thing hadn't happened Anne might have felt for me some day as I did for her. But, of course, it was such a dreadful shock te Gilbert that for a time he seemed really in & more pitiable case than I, and only Anne could comfort him. Besides, I should never have asked Anne to take a blind and disfigured man for a husband. They say it was a defective test tube. It must have been, of course. All I can recall is standing by Gilbert In the laboratory while he heated the tube over a Bunsen burner, and then the sudden searing agony. After months in & hospital they got me on my feet again. The sight of both eyes was completely gone. No one ever told me the rest, except that one time when Gilbert eouldn’t control himself, just before he died; but though I couldn’t see, I eould feel that my face was no longer the face I had known. Poor Gilbert! It was terribly hard on him. They took me to the ranch, and the only comfort there was for me in life was the oleander tree. I used to lie under it all day in the sunshine. I could reach up and touch its rough bark and the leaves and the flowers, and it was as if there were one friend left in the world from whom I need not shrink or hide. I clung to it morbidly, I suppose. I know that the day they told me Anne was going to marry Gilbert I threw my arms around its trunk and lay for hours with my scarred face hidden by its root. It is strange that eyes can shed tears when they can no longer see. After father died mother and I lived alone together. Gilbert and Anne were in the city. He had not become a chemist after all—I suppose it was too painful for him after what had happened. I don’t understand exactly what his business was, but it had something to do with stocks and bonds; I know, because of his trouble afterwards. They had a little girl, but she died. SHE was only 3 years old at the time, and &7 the circumstances were very sad, too. No one ever told me all the details, but as N \O‘I_th & Wods s, o0 g v v \ W et ‘s Once when I was lying under the oleander tree, just thinking, she stole up to me and took my hand and said I was her only, friend. I recall it, Gilbert had had to punish her for some trivial childish lie or something of the sort, and she ran from him and fell down a flight of steps. A child, of course, could not realize that Gilbert’s hot temper didn’'t mean anything. He had always had it, but his heart was warm—I am sure it was. They never had any more children. I kept away from mother all I could, for I knew how dreadful it must be for her to see me. It seems queer to think that before all this happened people used to think me handsomer than Gilbert. I never agreed with them, and I know mother didn't, either. Gilbert was always her favorite and father’s; that was natural, for he was fiery and demonstrative and impulsive, and I was always a dull, moony creature. But mother was very kind to me always, just as Gilbert was afterwards, and Anna. I used to conscle myself by being grateful that if one of us boys had had to be marred it was not the one mother loved best. One night Gilbert came suddenly to the ranch without Anne. Mother was in her room; she hadn't been well for several months, but we never thought it was anything serious. Night and day are just about the same to me; I spent all that evening sitting under my oleander, whittling. I had bzgun whittling just to amuse myself and to fill the time years before; I had really grown quite skillful at it, I think. I used to carve all sorts of things for mother to use, and I imagine she just pretended out of kindness and pity to like them and prefer them, for, of course, they could have been bought anywhere just as cheap and prob- ably much better. Bowls and potato mashers and clothes pins and bread boards, household things like that. So I was not even in the house, though I could hear Gilbert’s vpice distinctly, rather loud and very much excited. I know now that he was telling mother about his trouble. Something to do with bonds, I think; some man who claimed that Gilbert had misappropri- ated certain funds given him in trust, or some nonsense like that. Anyway, things were so complicated that there was danger of Gilbert's arrest, and I know how distressed mother must have been. But I suppose she herself would have wanted to know all about it. I remember wishing that Gilbert realized better that mother wasn’t well and mustn't be upset, when all at once I heard her scream. He must have just told her how bad things were; that must have been the reason. That fool of a Maggie, our old cook who rushed to mother's room while I was stumbling up the porch, and found her on the floor, tried to tell everybody afterward that Gilbert had struck his own mother. Gilbert was quite right to discharge her at once, in spite of her years of service; no one could tolerate a hysterical liar like that. I asked Gilbert myself what put such a thing into Maggie's head, and he said when mother sud- denly had the heart attack and fell, her fore- head struck the side of the chair and was bruised. Mother’s heart had been weak for years, and every one knew about it. I was not surprised when the funeral was over to find that everything had been left to Gilbert. After all, he was mother’s favorite and she knew she could trust him to take care of me. He could use money to good advantage, and all I needed was a bed and some food and my oleander tree. 'HAT was another of Maggie’s wild stories, that mother had shown her a will in which I was left half the estate. That was when Gil- bert had to threaten her with suit for slander if she said any more, and she never dared make such a ridiculous charge again. It was most fortunate, as it turned out, that Gilbert got the money just when he did, for it settled that unpleasant affair in the city and enabled him %0 retire from business for good. He and Anne gave up their apartment and came to the ranch to live. Gilbert was always kind to me, and if in some small ways he did not seem to be, I understood the reasons for it very well. For instance, I could quite under- stand that it must have been very painful to &mne to see me, and I don’t blame him for “Here’s something you can use,” I said, and brought out the four meat skewers. “Try them in the roast tonight, will you?” I was trembling so I could hardly talk. wanting me to let him keep me in a comforte able home or sanitarium or asylum or somee thing of the sort. But for the first time, I think, in my life I could not agree to that. I was so used to the old house, and I felt as if it would tear my heart out to leave my oleander tree. It was more than ever my only real friend and com= fort. I was quite willing to compromise, how= ever, though Gilbert had to lose his temper with me once or twice first. I agreed finally to stay in my room during the daytime and to go out only at night when they were asleep. The new cook brought me my meals, and it was really a better arrangement all around. For one thing, I discovered that, like the fool I am, I still felt just the same old way about Anne. I was just as glad to hear her voice so seldom and not to feel that she was so hope- lessly near me. That was three years ago. I thought a great deal about Anne. It seemed to me that she wasn’'t happy, though why I can’'t imagine. Of course, she might have been grieving over the little girl they had lost, or perhaps it was dull for her in the country; she had been a city girl. Certainly it seemed to me very foolish of her to quarrel with Gilbert, as so often I could not help hearing her do. Surely in all those years she should have grown to know, as all our family did, that his quick temper didn’t mean anything, that it was just his way. There was always a reason for it, and all anybody had to do was to say nothing and let it blow over —we always had since he was a tiny child. Even that time he shot Anne’s dog he was quite right in saying it had howled and annoyed him—I heard it myself, though perhaps it would have been better for him to have tried te control himself, since she was so fond of it. I confess I came nearer to being angry with Gilbert then than I ever had done before, especially after I heard her crying. But that he shot it before her eyes I can scarcely believe. All T could do to show my sympathy with Anne was to make the same little gimcracks for her that I used to make for mother, and send them to her by the cook. She was very sweet about it; once when I was lying under the oleander, just thinking, she stole up to me—Giibert would not have liked it at all, but he was at work on the ranch. HE took my hand and said I was her only friend. I had to seem quite cold and casual and send her away, for I was trembling s0 I could hardly talk. It must have taken tremendous courage for her to come close to me like that and look right at me, and it wasn't necessary. I told her so. Somehow I think Gilbert found out about it. Anyway that night I heard them quarreling bitterly, and several times I heard my name mentioned. It was all I could do to keep from rushing in and telling them that I wasn't worth upsetting themselves over. But I kept quiet, and after a while I heard a sound as if Gilbert were slapping his hands together, and then there was no other sound except a little whimpering that I suppose must have been the cat trying to get into the house. I called it, but I couldn’t find it. Two days later Anne went away on a visit to see some friends. Although I had heard so little of her around the house, it seemed very empty without her. It was almost as bad as when she stopped visiting me in the hospital at the time of my dreadful accident. I asked Gilbert when she would be back and he was very angry about it. I hope he didn't mean his answer the way it sounded. “Never, while you're on my hands,” he said. But where could I go? It was the next day while I was asleep in my room that I heard it happening. I knew instantly, springing from my bed, what it was. Continued on Twenty-first Pare