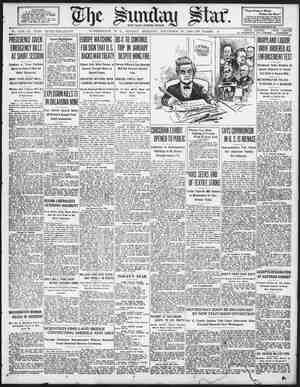

Evening Star Newspaper, November 30, 1930, Page 90

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

2 perhaps it forms a rivulet, to run to the near- est creek and scatter its fire for miles throughk woodlands and farm country. Truly, the burn- icg oil or gas well is a spectacle fraught with fright. There are several ways of extinguishing the burning oil well, and oftentimes all of them are tried on one well. The safest method is that of tunneling beneath the ground for 50 or 60 feet, so that a pipe may be connected to the casing and the oil drained from the fire into a reservoir. First, the site is cleared of debris by workmen wearing asbestos clothing—thick suits with a fireproof hood and equipped with a mica visor. Bulwarks of corrugated iron are built against the force of the heat and giant fans are installed at the site if there is no wind. Pumps and boilers are pulled up and the work- men are sprayed with water as they dodge in and out of the flames, snatching away with long iron hooks the pieces of red-hot metal that might reignite the weil once the first flame is snuffed out. The site cleared, the tunnel is constructed and a small room is fashioned about the cas- ing, so that those in charge of fastening the diverting pipe to the casing can move freely. It is a Jong job, and meanwhile the fire is consuming thousands of dollars in precious liquid gold. OTHER methods used in fighting oil fires include the spraying of the casing head with h’gh.pressure steam from a battery of beilers; the use, on small oil fires, of a smolder- ing device which is placed over the blaze by means of a cable stretched tautly between two posts through the very center of the roaring flame, and the use of mud and hematic spe- cially mixed and pumped under high pressure through a sort of moving hopper swung over the casing head. The oil field superintendent must make his preparations hurriedly, but well. Every fire presents a different problem to the engineer- ing department of the oil company, but to the workmen every oil fire is about the same. They all call for blistering hours only a few feet from a blazing inferno, and more than likély they call for sacrifice of health or even life. Even when a battery of boilers is used to subdue a burning oil well, the workmen must perform difficult feats. Unless the steam is released directly into the base of the flame it does no good. So the oil well crew must take charge of the nozzles. They strap them to steel wagon wheels, and while a steady stream of water is sprayed on them they advance into the furnace until the pipes are placed only & few inches from the spewing oil. When mud is pumped into the cas'ng the hopper first must be placed directly in the stream of ofl feeding the flame, so that the mud coming out of it under high pressure will equalize the flow of the well and cut off the supply of oil. Sometimes an oil well catches fire after i# has been brought in and the oil is flowing into a near-by earthen tank. When this happens the flame, Instead of shooting skyward, spurts out parallel to the ground—a very nasty sort of situation, indeed. The first problem is how to make the flame shoot upward, so that it can be snuffed out with steam. H'gh-powered rifles are then brought into play. Specially trained marksmen, standing a safe distance from the well, direct steel-jacketed bullets at the casing head until it is demolished. Often a thousand or so shots are required before the nozzle is broken off and the flame behaves as it should. It is in extinguishing the burning gas well, however, that the workman faces the most danger. Here the problem is different. The gas flowing from the well and ending in the bright plume at the top does not ignite uniil it is weli away from the casing. If this col- umn of gas can be severed, even for an in- stant, the flame will be snuffed out, much as one snuffs out a candle with the fingertips. Although the methods used in fighting ofl fires are used to a great extent on gas fires as well,. the, method generally employed in the oil fields today consists of using high explosives to sever the gas column, so the well will sub- side. As’in the oil well fire, bulwarks are con- structed, the site is cleared and the workmen are sprayed with water to ward off some of the effect of the intense heat, which is fiercer than that of the oil fire. This accomplished, the explosive—nitroglycerin or gelatin—is placed within a few inches of the casing and exploded by electricity—no small task, even in the oil flelds. { ’I‘HE business of placing a hundred or so pounds of gelatin or 30 or 40 quarts of nitroglycerin in the midst of the flame s usually delegated to the torpedo company oper- ating in the field. Once the site is cleared and everything is in readiness, a couple of daredevils, bearing between them the huge can of dynamite, walk directly into the flame. They are equipped with asbestos suits, of course, and the hoses spray them with water as they slowly and carefully work their way into the inferno. A stumble, a piece of flying debris from the well or a slight miscalculation would eliminate all traces of them from the landscape. The can and asbestos packing protect the ex- plosive from the intense heat until it is securely and safely placed within a couples of inches of the roaring column of flame. Then the work- men scurry to a safe distance and a distant watcher gives the signal to the detonator; the switch is thrown and the mighty blast shakes the earth and rattles windows 20 miles away. The debris falls in clouds, and when the atmos- phere clears the flame is no longer to be seen. Unless a piece of hot metal, overlooked when the site is cleared, reignites it, the hissing volcano has been conquered. Allowing an hour or so for the ground to cool sufficiently, the crews make their way back to the well to place the conneclion over the flow, so that the gas may be piped to safety. “Tex” Thornton fights fires alone because, he says, he doesn’t see any reason why two or three or a hundred men should risk their lives when he does the fighting so well by him- self. Besides that, he points out, his suits cost exactly $107—so figure wHat it would cost to have a lot of fellows walking in the flames in “Tex's” asbestos garb. And the suits last through only one fire. Because he charges a stiff fee—some say it is several thousand dol- - mensity of the black sky. THE SUNDAY STAR, WASHINGTON, D. C, ROVEMBER 30, 1990. _—_—_—,—m e { N Acme, A three-day oil fire that cost $4,000,000 near Los Angeles. lars—oil well owners do not call him except as a last resort. So “Tex” usually gets what he calls “the good and hard uns.” One of these “good and hard uns” was & burning gas well in the Taylor-Link field, in Pecos County, Tex., which Thornton recently . extinguished single-handed. The geyser, evi- dently ignited by a spark, had bezn roaring its head off for 24 hours when “Tex” arrived, equipped with an asbestos suit, a large cofl of asbestos rope and only 250 quarts of nitro- glycerin, The bulwarks werc reared and the site cleared of all debris. Then “Tex” began his maneuvers, while a thousand or so of the oil field curious gathered on the prairie nearby. He stretched the asbestos rope across the flame by tying it to an abandoned derrick on one side and a truck on the other, and pulled it taut by driving the truck away from the well. He then mixed a 20-quart bomb of nitro- glycerin, signaled the spectators that he was about to start the fireworks and suspended the nitroglycerin over the taut line with a loop of asbestos rope. He then tightened up the belt of his asbestos suit and started pushing the explosive along the rope into the fire. Trailing the protected wires of the detonator behind him, he walked slowly toward the bright column. The taut rope swayed a bit and al- most touched the casing. If it burned in two there would be no more “Tex” Thornton to thrill the people in the oil land! But it held, and he placed the charge within two inches of the casing head and began his hasty retreat. Out of range, he signaled for the detonator to let go. A blast that would topple a building rocked the prairie. The flame was snapped out, but the roar of the gasser, only a little diminished, kept on. An anxious moment, and it flared again with a booming sound. It had been reignited by a piece of metal. The whole thing was to be done again. By this time night was falling and the huge torch flared blue and orange against the im- Darkness didn’t worry “Tex” any, however, for he had plenty of light by which to work. This time he mixed a “shot” of 30 quarts of the “soup” as casually as one would stir sugar into his ) asbestos rope formed his guide thi as “Tex” waded into the sea of fire crowd cheered—a feeble endugh noise the roaring of the “gasser.” He D charge and retreated. Again the terrific made the earth quake. “Tex,” at what supposed was a safe distance from the was thrown for five or six yards on his head— uninjured. The flame was snuffed out. A vast darkness enveloped the plains. Stars, not apparent to those whose eyes had become ac- customed to the incandescence, looked down on a world once more at peace, “Tex” reck- oned “she wouldn’t need another shot tonight” and took off his suit with the satisfaction that here was a job well, but dangerously, done. If the burning gas well has been burning long enough to form a crater a much more dangerous problem confronts the firefighter. The caving earth creates fissures through which the escaping gas flows, and in a few seconds these secondary “blowouts” are burning as fiercely as the main flame. Then it becomes necessafy to place two, or even three or four, charges of dynamite or nitroglycerin, one in each of the fissures, and explode them simul- taneously. At any minute while the firefighters are placing these charges other fissures may open up to envelope them in flames and make their work extra hazardous. SIDE from the danger involved in fighting oil and gas fires, they offer difficult prob- lems in management because of their expene siveness. Extinguishing a well—if the well is saved and can be used as a producer again— costs somewhere between $1,000 and $70,000, depending on the number cf days it burns and the amount of oil and gas it consumes. If the well is lost the loss may range from a few thousand to $135,000, exclusive of its poten- tial production. As the oil flelds have become more extensive and the wild wells more numsrous the oil field equipment companies in a manner have met The “Stout Fella” gusher in Oklahoma City. the problem by building equipment that pes= mits the drilling of wells so that they may ba controlled no matter what happens. ‘This equipment, however, adds thousands of dollars to the cost of drilling a well. No driller brings in a gusher . intentionally, It is the unexpected that brings about gushing oll and hissing gas, and until a more complete knowledge of mother nature’s tricks is gained@ from constant exploration of the bowels of the earth with steel tools the “wild un” will con- tinue to be an actuality. And Oklahoma City, fringed about with potential gushers, may never rest comfortably until the last pool in the bountifully supplied oil fields is drained of its last drop of the precious fluid and the highly colorful troupers of the oil fields stage have transferred their properties elsewhere, there to re-enact their most thrilling exhibition—“Dante’s Inferno—Ameri- can Style.” Forest Fires Hit Trade much has been written about the loss in timber and the damage to farm land brought about by forest fires that it is easy to draw the conclusion that these two branches of agricule ture, forestry and farming are the only suffer= ers from the fires. This, however, is wrong, for there is an ine direct loss, chargeable to the fires, yet not con- sidered in the damages reported. Forest fires mean, for instance, a definite loss to hotels, service stations and others dependent upon tourist trade. Tourists apparently avoid forest fire areas as they would the plague, and, hav- ing stayed away during the fires, they are slow about coming back after the fires are over. As a resuit of this loss of trade, business ine tests in the vacation sections are co-operating with State and Federal authorities in efforts to eliminate or at least keep down outbreak of fire. A study of conditions brought about by the fires show, that in one section, during a fire, the tourist business dropped off 88 per cent., This loss of business had far-reaching effects, bringing declines to banks, building trades, real estate values and tax resources. Near the town in which the study was made, one hotel had 85 guests at the time of the out~ break of the fire. Six days later there were but 10 left, and a week after the fire was eX= tinguished the guest list showed but 58. Simiw lar observations have come from lake Statesy from New England and other sections free quented by tourists. Because of the fires I the upper peninsular of Michigan last August, thousands of Chicagoans who might have been expected to visit the section went elsewhere for their vacation trips. Wood Coating Sought. 'OR 15 years experts of the Forest Service of the Department of Agriculture have been experimenting and testing to find some kind of coating for wood which will exclude moisture entirely, and the net result has been the proving of the value of many treatments, but none has been discovered that can be said to bring about complete exclusion. The research work which is continuing ine cluded study of paints, varnishes, enamels, waxes, primers, lacquers, oils, metal leafs, pige menis and powders. All the coatings were applied according to accepted methods and were tried in all sorts of combinations and numbers of coats. The rew sults were noted soon after the coats were ape plied and periodically after exposure and weathering. Aluminum leaf coatings in combination with paint and varnish were most effective. Next in order were aluminum powder paints and varnishes. A few proprietary asphaltic and bituminous paints had good moisture resistance, Spar varnishes were found to increase in effece g;en:.; taa the number of coats were increased. e tion of pigments to the varnishes made them more resistant. Musk . Oxen on Long Trek GIVEN almost the attention whi_h would be accorded royalty, 3¢ musk oxen are well on their way toward the Reindeer Experimental Station in Alaska, on a journey from Greene land, in an effort to re-establish their species in Alaska. Half of the musk oxen are young, having been born this year. They arrived in New York on September 15, in roomy crates. Here they. had their first taste of changed diet, the native hay which they were fed on shipboard being changed to alfalfa. They seemed to like the new menu and thrived on it. After passing a month’s quarantine, they were loaded aboard freight cars and started on their overland trip to Seattle, where they were scheduled to be placed aboard the S. 8. Yukon for shipment to Seward, where they would again take to the rails for the final leg of their trip to Fairbanks. Antimony Bought Abroad. AN'I’!MONY, & metal vital to the printing trades and particularly to publishers of newspapers and magazines, comes almost entiree ly from foreign sources into the trade in this country. Mexico and China, in particular, are sources of the necessary supply. Antimony is mixed with lead in type metal in order that the metling point may be lowered and at the same time the cold metal made harder. Approximately three-fourths of the antimony brought into the United States i received in the metallic form, although much comes in amalgamation with lead. The metal, because of its low melting poing, s used in the manufacture of automatie sprinklers, serving as the trigger guard which melts at dangerous temperatures, such as might be caused by fire, permitting the water to flow through the sprinkler systems. £ {