Evening Star Newspaper, May 16, 1937, Page 38

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

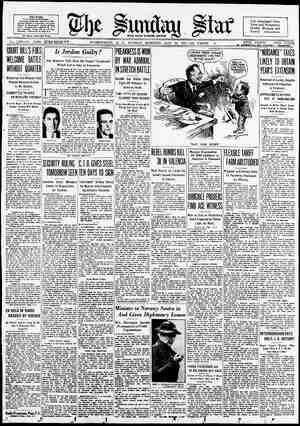

THE EVENING STAR With Sunday Morning Editien. WASHINGTON, D. C. SUNDAY _ SoasnR May 16, 1937 THEODORE W. NOYES --.Editor The Evening Star Newspaper Company. 11th St and Pennsylvania Ave. New York Office: 110 East 42nd 8t Chicago {'fice’ 435 North Michigan Ave. Rate by Carrier—City and Suburban. Regular Edition. Sunday Star The '“n:"' :ndflsé Ser month or 15¢ per week t The Evening St%. er month or 10c per week The Bunday Star —_. ¢ per copy Night Final Edition, Night F nal and Sunday Sta 70¢ per month Night Final Star. -56¢ per month Collection made ut the end of each month or each week, Orcers may be sent by maii or teje- phone Natior.al 5000 Rate by Mail—Payable in Advance. Maryiand and Virginia, 1 yr. $10.00; 1 yrl 862008 1 mo. 88c Sunday only. yr. $6.00i 1 m Member of the Associated Press. The Assoctated Press is exclusively entitled to the use for republication of all news dispatches credited to it or not otherwise credited in this paper and also the iocal news published herein, All righ s of publication of special dispatches herein are also reserved. The Issue Is Clear. Hearings on the King bill to ban nui- sance industries from the National Capi- tal have served admirably to crystallize public sentiment in support of this neces- sary legislation. What is more, the real issue at stake has been clearly estab- lished. The question is not whether the slaughtering of animals, the processing and rendering of the products, s a legiti- mate industry. Of course it is. The question is not whether the Gobel firm has the legal right under existing regu- lations to set up its plant in the District. That right has been recognized. The question is not whether a citizen is to be deprived of his property without due vprocess of law. Nobody is proposing to confiscate private property or to rewrite the Constitution. The whole question at issue is whether & slaughter house, rendering plant or other “nuisance” industries are to be given the continued right of location within the narrow confines of the Amer- lcan Capital, when their presence here manifestly places in jeopardy continua- tion of the policy of developing Wash- ington as the Federal City. But is this bill aimed at a single in- dustry? Why pick on the slaughter house? The bill is not aimed at a single in- dustry. It is aimed at all nuisance in- dustries. The slaughter house proposal has merely emphasized the danger of re- peating errors of the past, brought the whole issue in relation to National Capi- tal development to a head. Because errors have been made in the past, must they be perpetuated, ad infinitum, by addition of new mistakes? An awakened public sentiment is conscious of the dan- ger threatened by the slaughter house and demands that it be averted by prompt enactment of the necessary legis- lation. Testimony has shown plainly enough that the proposed slaughter house and rendering plant will adversely affect an area of the city which the National Government Is planning to develop and will tend to depreciate the Government'’s investment already made in contiguous territory. The time to remove this threat is now—not in the future when city plan- ners will be forced to spend great sums in the correction of a serious mistake, just as they have been retarded in the develop- ment of Washington by other mistakes of the past. It-required years of persevering effort to get the railroad tracks off the Mall. It required other years to transform the banks of Rock Creek from an ugly dump to the beautiful parkway it has become today. Years ago the location of a slaughter house in Northeast Washington was tolerated, just as the railroads of the Mall and the pigs on Pennsylvania Avenue were once tolerated. But this is another day. Washington has grown rapidly in the past and this growth continues. The plain fact is that there is no longer any room for such industries as slaughter houses and ren- dering plants within the limits of the District unless the traditional concept of the city’s development as the Capital is to be thrown overboard. The whole tend- ency in city planning now is to prevent, by wise foresight, the creation of the blighted, rundown districts which are such eyesores today. The creation of such districts within Washington, where the city limits are fixed and non-extensible, is a more serious mistake than in any other city. The opponents of the King bill are actuated by their own interests. The proponents of the measure are working to preserve the character of the Federal City. ——oe—s. ‘The Japanese have established a valued annual reminder of good will. What their learned men would think of dis- turbing the annual lure of the cherry blossoms would be worthy of serious end intelligent consideration. ——o—s Philip Snowden. Those who knew Philip Snowden Marveled at the spiritual miracle which he worked in himself. Small and weak and frail from boyhood, pathetically i1l in his later years, he triumphed over his physical handicap as few men ever have. The wonder is that he lived at ell, not that he managed to reach seventy-two years of age. His career, like Dr. Samuel Johnson's, was “a long disease.” Yet it was wonderfully rich in service to the common good, bright in achievement far surpassing the suf- ferer's most ardent expectation. Perhaps pain taught him the lessons of optimism, tolerance and charity which he exemplified in everything he thought and said and did. Snowdes understood from experience the profoundest mean- ing of mercy. His soul sympathized with humanity in its struggles because he was on terms of intimate acquaint- v ance with agony of mind and body. War he hated with a passion bred of overmuch familiarity with its correlative phenomena of death, prodigious labor wasted, brave hopes destroyed. Class strife he also deplored for the same sufficient reasons. He gave the best of his genius to the problem of resolving conflict into co-operation, mass murder into mutuality and fellowship. It surely is not remarkable that he was respected by all parties. His de- voted wife declared that she “fell in love with him when she saw his smile.” Thousands could echo that sentiment. But his countenance in repose was equally attractive. The eyes at such a moment were those of a beaten child, the mouth trembled with the earnest- ness of an unspoken appeal to whatever power there be in the cosmos for the help of mankind. Critics who imagined him cold and bitter never looked into his face. They would have found their answer there—and in their own re- sponsive hearts. Parliament did not need to be asked to cheer him when he concl* * 1 his supplementary budget speeci 3eptember 10, 1931, with Swin- burne’s magic words: “Come the world against her, England yet shall stand!” He was carried into the House, Ramsay MacDonald supported him to his seat, but no other chancellor ever was so little lacking in public confidence. The empire applauded him. Now it mourns for him, and America proudly shares in its grief for its lost benefactor. D Uncle Sam at London. If President Roosevelt and Secretary Hull had been present in the flesh at the opening session of the Imperial Con- ference in London, American influence upon its deliberations could hardly have been more impressive. The atmosphere in question was provided by Prime Min- ister Mackenzie King of Canada, who boldly and unequivocally identified him- self with the Washington Government's reciprocal trade agreements program. In effect, Mr. King enacted the role of & missionary for the Roosevelt-Hull idea that the way to international peace is through the smashing of artificial eco- nomic barriers. Seldom has there been more graphic demonstration of the theory that Canada is the bridge be- tween the Americas and the British Em- pire, or more convincing evidence that in the realm of broad foreign policy the Dominion and the United States nowa- days see eye to eye. The head of the Ottawa government, plainly reflecting the results of his re- cent conferences in Washington, told his fellow representatives of the British Commonwealth of Nations that they have “a definite responsibility to join with other countries willing to co- operate in a concerted effort to avoid increasing tariff and exchange or quota controls, and to lessen in every prac- tical way obstructions to world com- merce.” Following this frank invitation to Britain and the dominions to follow the American example, Mr. King de- tailed how Canada had moved con- cretely in that direction. Negotiations with the United States and more re- cently with Greai Britain had led to substantial reductions in the Dominion's tariff rates. In no instance were con- cessions to either country effected by raising duties against any other nation. Canada plans to proceed along these lines with countries both within and without the British commonwealth, per- suaded that it can thus make the most substantial contribution to revival of trade and consequent removal of inter- national friction and conflict. The case for economic understanding, as the bed- rock of world peace, could not have been more effectively argued even by the ardent proponents of that policy in Washington. It, of course, remains to be proved whether the Imperial Conference can bridge the yawning differences which separate the empire nations on trade and many other grounds. English pro- tectionism is the antithesis of the Ca- nadian prime minister’s tariff liberalism. South Africa’s nationalism runs counter to the traditional empire loyalty of New Zealand and other dominions. On the paramount issue of imperial defense, a way must be found to reconcile Great Britain's European commitments with dominion fears of Old World entangle= ments. The mother country is con- scious that it cannot compel the daughter nations to contribute to the $7,500,000,000 rearmament scheme necessitated by de- velopments wholly outside the dominions’ sphere, except possibly in the instance of Australia’s yearning for safety against the Japanese danger. Vaunted British genius for compromise faces an acid test in the necessity to grapple with the complex and perplex- ing agenda of the Imperial Conference. — As to what Hugo Eckener thinks about the loss of the Hindenburg no intelligent assistance can be given. A series of in- telligent interviews will, however, surely be of assistance in guarding against a repetition of the calamity. o Trailer Cities. The sponsors of the New York World Fair of 1939 are planning a three-mil- lon-dollar trailer camp for the accom- modation of visitors expected to motor to the scene with their domestic estab- lishments behind them. A natural de- velopment of the same idea would lead to trailer cities scattered all over the map. But, of course, such communities would be likely to be mobile, or, at least, mutable in character. The moment Citizen John Doe found himself rest- less he would “hit the road” again. Meanwhile, his temporary neighbor, Richard Roe, responding to similar im- pulses, might “pull up stakes” without notice and chug away into the infinite. In a few days the two automotive vaga- bonds would be hundreds, perhaps thousands, of miles apart. A serlous problem, it seems, is in- volved in soclal fluidity of so free a type. The business of maintaining the necessary machinery of government re- quires a certain constancy of residence among the people. How, for instanle, is the tax collector to keep track of Doe ’ THE SUNDAY and Roe in their wanderings? Again, education may be mentioned as an as- pect of the dilemma. What chance of regular schooling will the little. Does and Roes have, if their parents insist on living “on the run”? Possibly it is logical to expect that crime will increase in proportion to the growing popularity of bothering with no fixed abode. Epidemics of disease, finally, could be spread effectively enough by the trailer system of existence. It may be granted for the sake of argument that America is a free coun- try and that there is no law against exercising the privilege of possessing no home save a caboose. The enthusiasm with which vast numbers of families have adopted the policy of constantly “moving on” is evidence of its attrac- tiveness. But the question remains: Should the practice be stimulated? Un- less it be agreed that it is the best of all available devices for the strengthening of useful social ties, it is indicated that it ought not to be promoted arbitrarily. Trallers, surely, are a wonderful inven- ton. Yet it cannot be demonstrated that they surpass walls, doors, windows, & roof and a hearthside that “stay put.” ) New differences in valuation arise in & Harvard vocabulary. The good old college still encourages the production of interesting theories by which able men engage in enlightening quarrels without indicating more than the human hope that a good brain, used like that of Oliver Wendell Holmes, will remain long in useful service. o By the time money experts get through burying the stuff there may be a read- justment that makes values dependent on something that depends on a new and different word to indicate valuation. In the meantime, however, a number of Government attaches will have found a good living in Kentucky soil. ——oe—s. As a matter of fact, every change of administration represents an effort to talk over a “new deal,” but with an idea of getting away from elements of need- less hazard in applying an old one. In so simple a matter as costume, feminine fashions continue to hold a respect for the ancient standards of propriety. — e Old ideas come forward for responsible consideration in a new deal. Mr. Ham- ilton Fish asks a few questions about the valuations that are to be reliably em- ployed in commerce if it is decided to adopt an entirely new system of figuring commercial values. ——oe—s. After G. Bernard Shaw heard all about the coronation he did not approve of it, a fact which will convince anybody of his consistency of purpose regardless of his facility in handling arguments. o Shooting Stars. BY PHILANDER JOHNSON. Trying to Be Good. When you were just & little boy “A-tryin’ to be good.” How frequently you would annoy The peaceful neighborhood And hear your father say anew, As tears fell fast and hot, “It hurts me, son, much more than you"— You knew that it did not. Your brother laughed at your disgrace As you refused a chair, Your mother kissed your tear-stained face And smiled and said, “There! There!” For mothers more than all the rest Have always understood How boys may fail who do their best “A-tryin’ to be good.” It needs experience so stern To make life’s pathway plain; It needs a lot of years to learn To curb a restless brain. Some boys grow up as men of note For courage, strength and skill And some, though old enough to vote, Don'’t learn and never will. X you should help at duty’s call To mold the social plan, Reproving follies great and small That fret your fellow man, A moment now and then employ— T'would help you if you could— With recollections of that boy “A-tryin’ to be good.” Keeping Them. “Can you keep all your promises?” “Yes,” answered Senator Sorghum, ‘“some of them on file indefinitely.” Belated Regret. “A great many people do things they are sorry for,” said the readymade philosopher. “Quite true,” answered Miss Cayenne. “But many of them do not realize how sorry they are until the facts come out in the newspapers.” Human Confession. I've made mistakes. The fate I've shared Of mortals who have gone before. Moreover, if my life is spared, I know I'm going to make some more. Jud Tunkins says it begins to look to him as if it were either wonderfully easy to make money or absolutely impossible. “When you denounce the conduct of others,” said Hi Ho, the sage of China- town, “can you be sure that you would not have imitated it had the temptation or opportunity been your own.” In the Merry Springtime. The elephant I once admired, His size now makes me fidget And from my favor is retired. I'd like to be the midget. The elephant is never gay, His style is far too nosy. I'd rather be petite and play Ringling around the Rosy. “I likes to hear good speakin’,” said Uncle Eben, “an’ I ain’t yet found an oratory dat satisfies my mind as much as my old friend de preacher.” . 4 STAR, WASHINGTON, D. President Returns to Find a Political Mess BY OWEN L. SCOTT. President Roosevelt got back to the White House after seventeen days of vacation to find himself in a political mess. Life was nearly gone from his court change plan. Congressmen were squabbling all over the place about economy, the Supreme Court and just plain politics. Cabinet members had ‘worked themselves into a dither over the fate of their pet plans in a period of economy. What to do? Mr. Roosevelt is pondering an answer that he can’'t yet give. The fact is that, for one of the few times since taking office, events have maneuvered the President into a corner. Chief Justice Hughes, by bringing a shift in court attitude toward State minimum wage laws and Federal labor laws, caught President Roosevelt off guard. The next move, the cards show, still is up to the Supreme Court. With one deeision, due on any one of the next three Mondays, the court can: Pump life into the President's plan to add more justices, knock the Federal Government budget further into & cocked hat, cause acute official headaches, stir Congress into a burst of activity. Or the court can: Make probable a quiet death for the court plan, take a load of financial worry off the Treasury, ease administrative strains and encourage Congress to remain definitely tired of experiments. * ok ok K The key to the immediate future is held, not by the President or by members of Congress, but by the “keyman” on the Supreme Court, Justice Owen Roberts, 62, youngest of the justices. How he uses the key he holds will determine the fate of the country’s new unemployment insurance and old- age insurance systems. And the fate of those systems will almost surely de- termine the outcome of the, impasse that now exists in Congress and in the relationship between President Roosevelt and Congress. History is wrapped up in the moves expected during the days just ahead. An odd situation within the Supreme Court heightens the drama of the present situation. Past decisions on constitutional issues similar to those involved in this country’s social security act suggest that four members of the court are definitely of the opinion that this act is in conflict with the Constitution. Those four voted against the New York State unemploy- ment insurance law, as well as against the railroad retirement act and the agri- cultural adjustment act. They are Jus- tices Van Devanter, Sutherland, Mc- Reynolds and Butler, constituting the conservative group. * *x Xk X Those past decisions suggest that three other members of the court, Justices Brandeis, Stone and Cardozo, will almost, certainly approve the social security law. They voted in favor of all three of the other acts. Chief Justice Hughes approved two of them, but went with Justice Roberts in overturning the A. A. A. Justice Roberts wrote the decisions that ended the first old-age pension system for railroad workers and the New Deal farm control program, using strong language in each. He approved the un- employment insurance system for New York. This time, the decision, when made, will affect 28,000,000 workers and em- ployers. It will involve old-age insurance for 26,000,000 workers and unemployment insurance for a large proportion of those same workers. Taxes, figured at more than $700,000.000 for the next year, are at stake. The coming decision touches a program that was a major issue in the 1936 presidential campaign and re- ceived an overwhelming indorsement at the hands of the voters. The turn that decides the fate of his social security plan, President Roosevelt is convinced, will be called by Justice Roberts. Which way will it be? Nobody outside the court knows. But: Court approval of the social security system would make retreat easy from the President’s plan to add new justices. Mr. Roosevelt could tell the country that the court majority now had altered a view point that appeared before to block his plans. He could decide to push ahead with the remainder of the legis- lative program originally mapped out for a Congress that today is restive and angered over its enforced idleness. Many members, who came in January full of zest for reform, now want nothing more than to go home. On the other hand, court disapproval of old-age and unemployment insurance ould force the President to recast some of his major policies and could cause him to drive harder than ever to bring a change in the complexion of the court. In that event, retirement of two or more justices, now being predicted for the Summer, might be the one develop- ment that would forestall an act of Congress adding new members to the court. * Xk Kk X The relationship of Justice Roberts to this whole complicated situation is most unusual. Events of the past few years show that the attitude of this one court jus- tice has had a determining influence on the course of Government policy. His position, in this regard, grows from the sharp division in the court—with four conservative members voting as a unit on most important issues. The record of decisions involving constitu- tional questions discloses the develop- ment that has caught the eye of the President. The official record shows that, in cases involving the overthrow of acts of Congress on the ground that they violate the Constitution, Justice Roberts has been found dissenting from the majority opinion just once during his term on the bench. That one case concerned a tax matter of relatively minor importance. In this regard, his record is close to that of the conserva- tive group on the court, which shows that Justices Butler, Sutherland and Van Devanter have no dissents and Justice McReynolds one, in cases that involve the upset of acts of Congress. Yet, when Justice Roberts votes to uphold an act of Congress, the conserva- tive group, which is a majority when he votes its way, immediately becomes a minority. The record thus brings clearly to light the key position held by the justice from Pennsylvania. This position is all the less comfortable for the decision that is expected to be made before the court adjourns on May 31 or June 1. The record reveals that, when Justice Roberts has joined with the liberals to uphold controversial acts of Congress or of the States, the conservative group is found among the dissenters—dis- senting against court approval of those acts. This was true in the decisions upholding the Federal labor relations act, the Washington State minimum wage act, the dollar devaluation act and the New York State and Virginia State acts permitting price fixing in milk. On the other hand, a swing by Justice Roberts to the conservative side adds to the already impressive number of dissents on the part of the liberal group. ‘These dissents are against overthrow by the court of acts of Congress. Among them are strong dissents in the A. A. A. - C., MAY 16, 1937—PART TWO. A COMPELLING BOOK BY THE RIGHT REV. JAMES E. FREEMAN, D.D, LL.D, D.C. L, BISHOP OF WASHINGTON. A group of men were sitting about a campfire. They were tired-out city men whom the late Senator Beveridge de- scribed as having “non-productive brains and sore, ragged nerves.” They were more or less broken in body and tired in mind and they had sought the big open for refreshment. Far from the crowded streets of the big city, they were living close to Nature's heart. They had hunted and fished, and now, after the noonday meal, they were seeking for some kind of mental relaxation. “I want something to read,” said one. “Well, what's the matter with the Bible?” said his comrade. “Oh,” said the first, “I don't want any- thing dull.” Whereupon a discussion ensued as to what the Bible really contained. The men at the campfire were thoughtful, yes, intellectual men. They had an ap- preciation of literature, but not one had ever conceived the Bible as other than “a dull book,” a book for Sundays and preachers, yes, and possibly for senti- mental folk and little children. He had never thought of it as other than a preacher’s text book, it had made no ap- peal to him as containing incidents, nar- ratives, bits of history, poetry, romance and countless other things rich with human interest. Like most people, he had read the Bible in his youth because he had to. It was a volume of stern discipline, shadowy and gray, and now, as a man, he had put it aside as unentertaining and perhaps uninspiring. Here is where so many make their mis- take. The Bible is more than a book, it is a library of 86 volumes, 39 in the Old Testament, 27 in the new. We might reverently call them, for the purpose of distinguishing their relative position, the Old Library and the New Library, not forgetting, however, that the two are intimately and indissolubly related. Again, it might help us to know that these two libraries may be classified simply as follows: The old one con- taining law, history, poetry, prophecy, with other sub-headings; the new con- taining the gospel or good tidings of Jesus, history, letters and finally that unique and mysterious book known as the “Revelation of St. John.” We have sometimes thought that it was a mistake to break up the Bible into chapters and verses, because it prompts the reader to read by chapters and verses rather than by subjects. In Mr. Beveridge's estimation, the Bible has more good reading, yes, and interesting, than that contained in any other book in the world. Here is his own testimony: “Many years ago in a logging camp, there happened to be nothing to read, and I just had to read. I had read everything—that is to say, I had read everything but the Bible. And I did not want to read that. I had read it over and over again in the church and in my own home, and always with that mo- notonous non-intelligence, that utter lack of human understanding that makes all the men and women of the Bible, as ordinarily interpreted to us, puttylike characters, without any human at- tributes. But there was nothing else to read. So I was forced to read the Bible, and I instantly became fascinated with it. I discovered what every year since that has confirmed—that there is more ‘good reading’ in the Bible than in all the volumes of fiction, poetry and philosophy put together. So when I get tired of everything else and want some- thing really good to read, something that is charged full of energy and human emotions, of cunning, thought and every- thing that arrests the attention and thrills or soothes or uplifts you, accord- ing to your mood, I find it in the Bible.” We think the late Senator was right, and we further think that there has never been a better time, certainly not in our generation, for reviving the sub- ject of Bible reading. Theodore Roose- velt read its immortal stories to his children because they were the greatest and most fascinating in any literature in the world. Our mothers told us these stories, along with the priceless truths that we may never forget, and there is no book with more sacred associations than this book that the dying Sir Walter Scott called for and upon which he pil- lowed his hand as he went forth on the Great Adventure. Apart from its sacred character, we may not forget that the best English we possess is found in the King James version of the Scriptures. It is little wonder that the late President Hadley of Yale once told a group of college students that no man could regard him- self as educated who was unfamiliar with the text of Holy Writ. We need this book in all the departments of our twentieth-century life and, reverently read and studied, it becomes as “a lamp unto our feet and a light unto our path.” Fifty Years Ago In The Star “Many of the army of Government clerks who will be affected by the new : \¢ Clerks Are Disturbed gn‘el ,fi:}g? By Civil Service Rule. ing promo- tions in the departments,” says The Star of May 9, 1887, “realize that they will have no easy work in retaining their positions. In the War Department, where the new rules will be applied first, may be seen arithmetics, geographies, grammars and other school books on the desks of clerks who hope to snatch a little spare time in which to brush away the cobwebs from their brains before they are compelled to enter into competitive examination for promotion to positions above them. It has.been said that the new rules are de- signed to rid the Government service of Republican clerks who have managed to hold on to their offices with the aid of civil service reform. “An official in one of the departments, himself of Republican proclivities, said to a Star reporter today that the changes will not affect any clerk unless it is shown that he is incompetent to remain in office, and then it will be his own fault. The best men will be promoted on their merits and those who fail to get seventy- five per cent in the examination will have nothing to complain of, as they will be allowed six months in which to fit them- selves to show that they are deserving of attention in office. Heretofore, he said, there has been no necessity for clerks to study.” * * % On the same subject of the civil service rule, The Star editorially, on May 13, . 1887, says: Scholastics and "1 the examinations Promotions. are not to be suffi- ciently scholastic to bother any practical, efficient clerk and the marking for practical efficiency is to control if he is bothered, of what service are the scholastic examinations? The clerk may, without the rules, be exam- ined and tested as to his practical effi- ciency and discharged if inefficient or retained and promoted if efficient. If there is any foundation for the slander that the vast majority of old Government employes are incompetent and unfit to hold office, why were they not discharged long ago for inefficiency, under powers then and now existing? If the new rules leave the opinion of a clerk's superiors as to their competency still to control, what reason is there to expect a change in that opinion which shall bring about proper dismissals, previously denied? The truth is that the new regulations, as amended by ‘definitions’ which, for the most part, do not define anything in the rules, but add new matter of importance, are so muddled and uncertain that they please nobody, neither civil service re- formers nor spoilsmen, actual nor would-be clerks, and promise no im- provement of the public service.” case, the municipal bankruptcy case, the railroad retirement case and the Guffey coal act case. Now, the all-important question, from the President’s standpoint, is: On which side will Justice Roberts be found when the fate of the social security law is determined? * ok kX Chiet Justice Hughes is credited with an historic selling job in the shift of Justice Roberts to the liberal side on the subject of State controlled mini- mum wages and federally controlled labor relations in industry. But until there is a decision on old-age insurance and unemployment insurance, Congress will be left to fret and fume. The Presi- dent will be able to do little more than continue his course of stalling. A strained situation in Washington will be expected to grow more strained. Gestures that may be made will be de- pendent on the outcome of the social security cases. Mr. Roosevelt decided early this year to maneuver the situation in Congress in such a way that everything important got backed up behind his court plan. Congressmeh have been on the job for more than four months, doing' little more than vote for appropriations and for extensions of powers already in the hands of the White House. This en- forced idleness has added nothing to the normal good nature of the Senators and Representatives, nor has it added to the President’s prestige in Congress. President Roosevelt traces all of his present troubles to the uncertainty concerning the position of Justice Roberts, as the “keyman” on the court. (Coprright, 1937.) Capital Sidelights BY WILL P. KENNEDY. The Coast Guard has taken to the air in a big way for better performance of its multifarious duties, which the public generally “wots not of.” Tribute to the efficient services of this important branch of the Federal service is given by Rep- resentative John H. Tolan of California. He points out that ten air stations have been authorized for the Coast Guard and nine of those have been already located —six on the Atlantic Coast, two on the Pacific Coast and one about to be estab- { lished on the Great Lakes. The Atlantic Coast locations are Salem, Mass.; Cape May, N. J., about to be put out of com- mission by a new one under construc- tion at Floyd Bennett Airport, N. Charleston, S. C.; St. Petersburg, Fla.; Miami, Fla.; Biloxi, Miss.; San Diego and Port Angeles, Calif. The tenth station is to be placed somewhere between Charleston, S. C., and New York. ‘The principal duties of the Coast Guard are summarized by Mr. Tolan—preven- tion of smuggling, enforcement of cus- toms laws, enforcement of navigation and other laws governing merchant vessels and motor boats, enforcement of rules and regulations governing the anchorage of vessels, enforcement of laws relating to oil pollution, enforcement of law rela- tive to immigration quarantine and neu- trality and saving of life and property along the coasts of the United States. Last year the Coast Guard searched 8,371,212 square miles of area, Mr. Tolan points out; its airplanes cruised 837.696 miles with 8959 hours in flight; identi- fied 51,694 vessels, identified 6,836 air- planes, responded to 118 requests for search, assisted 1,013 persons, assisted 430 vessels, transported 85 emergency medical cases, gave assistance in 233 cases to other Government agencies, lo- cated 70 foreign smuggling vessels, lo- cated 34 American smuggling vessels, sighted and reported seven suspicious airplanes, located eight smuggling land- ing fields and located and seized 402 stills. * kX X “West Virginia leads the Nation,” Rep- resentative Jennings Randolph boasts, after studying a comparison of percent- ages of eligible voters in the 48 States. He claims that “‘West Virginia was far ahead of all the others with a percentage of 92.1. West Virginia is credited with 900,- 987 persons over 21 years of age based on 1930 census figures, and the total voting in the 1936 election was 829.945. If the alien population of some 24,000 is deducted the voting percentage would be increased to 94.6.” Compared with this the figures for the entire United States are “appalling,” he points out, with only 67.5 per cent actu- ally taking advantage of this precious right in the last presidential election. He cited figures which show that in South Carolina only 14.1 per cent voted, in Mississippi only 16.2, in Arkansas, 18.5, and in Georgia, 19.6. Representative Randolph warned that “the future of our democratic system of Government in national as well as in State affairs rests with the citizens of the United States. It is only when we have an electorate that acknowledges not only its opportunity to vote, but rec- ognizes its responsibility to do so as well that we shall hope to have the fullest expression of the principles of govern- ment by the people.” He said he hoped the other 33 per cent of the citizenship might be awakened to their duty. * K K X Within the coming year South Dakota expects to place its first figure in Statu- ary Hall in the Capitol, a replica of the statue of General William Henry Harri- son Beadle, now in the rotunda of the State Capitol—on the centennial anni- versary of his birth. Representative Francis M. Chase of that State has given a tribute to General Beadle, whom Lincoln made a colonel by brevet “for gallant and meritorious conduct in action.” It was this soldier who spoke these words: “Political institutions whose foundations rest upon public opinion can never be secure unless all the people are educated.” Representative Chase re- called that he was “born in Indiana, educated in Michigan, lawyer in Wiscon- sin, surveyor general for Dakota Terri- tory, first superintendent of public in- struction in South Dakota, and author of the constitutional sections that have guarded the school lands of the States * that have come into the Union in the last fifty yenrs,'; * * % Supplies, transportation and services for the Army and the C. C. C. boys in flood relief activities amounted to about $8,000,000. The Pomp of American Service Uniforms BY FREDERIC J. HASKIN. The American press has had quite a little to say about the formal dress which the special ambassadors of the United States to the coronation of King George VI of Great Britain wore. Particular attention seems to have heen given to the uniform of the general of the Armies, John J. Pershing. Perhaps it has seemed a trifle strange that Black Jack Pershing, the hard-boiled cavalryman of empire days in the Philippines, should. appear bedight in pounds of gold braid, al glittering like a Broadway electric sign. There is nothing to wonder about. There are very few people who do not dress up when they get a chance and soldiers are especially given to such practices. Pershing is the first man in American history who has held the title of general of the Armies and there is no military power on earth which can tell him what to wear. Any officer who bears the title of full general—and there have been but few of them—has the privilege of designing his own uniform. The chief of staff of the United States Army bears the title of general while serving as chief, but, unless there is a special act of Congress conferring the title upon him after his term has expired, he re- verts to the title he held before having been appointed chief. * kK In the case of Douglas MacArthur, until recently chief of staff, he has managed to retain his prerogative of designing his own uniform through get- ting himseif named a field marshal of the Philippine Army. He can let him- self go, can carry a field marshal's baton, which no United States officer can be- cause the post of field marshal does not exist here. General Pershing and Field Marshal MacArthur have always been snappy dressers. Indeed, they were con- sidered the Beau Brummel and the Beau Nash of the American forces. As a matter of fact, General Pershing in his specially designed uniform a Special Ambassador Gerard in his black satin knee breeches, on the occasion of their attendance at the Westminster coronation, looked as somber as pro- fessional pallbearers, compared to the way American officers and even private soldiers looked in the earlier and gaudicr days of this Nation. There has been a sore decline in show-offishness among modern Americans. In his autobiograph for example, John Hays Hammond, who appeared officially representing United States at the coronation of K George V, said that American diplomats were especially conspicuous at court functions because of the quaintness of their simple satin knee breeches. Thev stood out like sore thumbs. They wou have appeared far more modest and democratic had they been attired in colorful robes as were the other noted guests. It seemed a bit of American bravado to wear such conspicuously plain clothes. * oK ok ¥ The American troops in the Revolu- tionary War were picturesque i extreme. Every American is fam: with the blue coats and buff trousers, with boots or leggings and white sal: crossed straps passing from belt to 1 shoulders. worn by officers and men of the Regular Army. In addition there were many independent militia comse panies. There were soldiers who wore Jjackets and trousers lavishly edged with fur and ooonskin caps with dangling tails. There was nothing drab about those boys. The early artillery uniforms were prob- ably the gaudiest. Artillerymen affected red to a large extent. Blue coats con- trasted with white breeches, but the lapels and the skirts of the coats showed revers of bright scarlet. All hands, in outfits, ran strongly to buttons. Ast Nation was established and the ind pendent militia, going home to farr and forest, left only regulars, a grea standardization of uniforms appeared and, as though in celebration of inde- pendence, a more superb showiness. Even private soldiers wore helmets with cox- combs of bristles arching down their centers. They resembled the helmets of Roman centurions. The infantrymen-—private, not offi- cers—of some of the War of 1812 troops looked more like members of the chorus of some extravaganza than soldiery. With blue coats and white breeches, these gallant soldiers wore top hats, much the shape of coachmen’'s hats and cockaded. Then there were other types which looked like butter churns. Officers wore fore and aft hats, feathered and plumed. The uniforms of officers left little space uncovered by gold braid or other ornamentation. In the Mexi- can War period the comic opera cos- tumes were carried, if possible, even further. There were helmets and chapeaux which looked like the more ornate ones of the armies of Napoleon. There were tall hats or caps. prettv near a foot tall, and surmounted by erect pompoms, which looked like especiallv bushy ribboned papered toothpicks stuck in lamb chops, only on a larger scale. ok %k The Civil War brought more sober military attire. The darker blue was introduced and coat and trousers of most outfits were of the same sha Others wore trousers of a lighter bl For fatigue duty the uniforms w: plain. Every one remembers Grar squarish slouch hat. Cavalrymen wi soft hats cocked on one side, with & feather sticking from the band on t other side. Beards seemed to be & p of the uniform of the day. There w some outfits which, indeed, wore helm with spikes rising from them, alm exactly like the German spiked helme of the World War. Full dress was gaudy enough. The dark blue of the uniforms was heavy with gold braid. Epaulettes like wedding cakes adorned the shoulders. Besides the gold belt, high-ranking officers wore gold sashes or scarves which passed over _ the left shoulder, tied on the right side at the belt and ended in a finial tassel of heavy gold threads. All through the years the uniforms of the West Point cadets were gorgeous affairs. Hats were high and jackets were striped and barred, and buttons of brass studded the cloth. The Spanish War first introduced the khaki and there was a general simplifi- cation of military attire so far as the fleld was concerned. Even then there were more or less private militia com- panies like the famous Richmond Blues and the Cleveland Greys which wore their own brilliant uniforms just as, in the Civil War ' there had been some Zouave companies, wearing Charlie Chaplin pants, some of them striped like sticks of peppermint candy or barber poles. Full dress continued brilliant. One thing about the full dress of high officers in the ’twenties is curious. Whereas the officers of the Civil War wore the sash over the left shoulder, tying at the belt on the right side, the officers after the Spanish War wore the sash over the right shoulder and coming down to the left side. At any rate, Gen. Pershing will have to think up something a little wilder if he hopes to live up to the standards® of early American uniforms in the days when we were supposed to be a simple people. Py