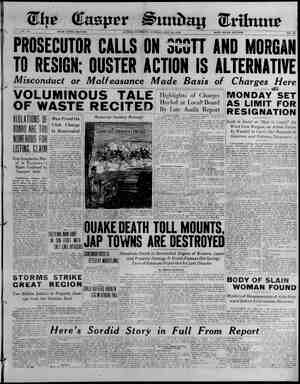

Evening Star Newspaper, May 24, 1925, Page 76

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

Wo ERE is a barrier, even im| America, between the sons of | men who carry a dinner pail | and the dauchters of men | who have had money and | power and place for generation The only question is what, precisely the barrier Jimmy McLean was the son of a Scotch stone mason who had come to America as a young man, settled in the old Connecticut village of Deep Harbor and built himself a cottage of | the native stone with his own hand: Jimmy learned the difference between £ood masonry and bad as he grew. At 10 he wanted to be a mason like | his father; at 15 he decided to be a | contractor and buiflder besides. But, | before he was 20, he walked down a | lane, in May, between two rows of | ancient apple trees with Cynthia | inwright. And nothing in his life | s ever the same again. The Wainwrizhts lived (when they weren't in New York or London 1 Paris) at Round Hill, in a white house that overlooks Deep i « house with tables by Phyfe, and early-eizhteenth-century silver, and a | late-nineteenth-century butler named | Wiggin. Cynthia's great-grandfather | had owned clipper ships: her grand- father had been Ambassador to France; her father had died in Tibet, in one of those early sporting at tempts to climb Mount Everest. Her brother Hugh, who had become head of the family on his father's death,! had two hobbies: Arab horses and tenni i Jimmy was the fair-haired boy of | Deep Harbor, the sort of boy other | bovs follow and older people admit | has something in him—if he ever | settles down. But he was the son of | # man who worked with his hands | and he might have lived all his life | in sisht of Round Hill and have be. come the town's leading contractor and builder without ever handing his hat to Wiggin save for a chance. The chance was that he was born to | keep his eve on a ball and his weight moving forward while making a full swing with his rizht arm and so he never had to learn the lesson that makes all the difference between the kind of tennis you see everywhere and the kind vou see at Forest Hills or Wimbledon or Cannes. i UGH WAINWRIGHT saw Jimmy playing one afternoon on the high school court and stopped hi roadster to watch a moment and stayed to_introduce himself. “Look here,” he said to Jimmy. “I wish you'd come up to Round Hill tomorrow afternoon and play with me. I think I could teach you to beat me.” That was the highest compliment a Wainwright could pay anybody. Jimmy blushed, stammered said, “T'd like to.” Jimmy walked the long miles up to Round Hill the next afternoon ——up to Round Hill and through the great iron gates and into another world. Jimmy got only one game in his first set with Hugh Wainwright. He w still awestruck and the unfamil- far bound of the ball off the turf dis turbed him. But he worked hard, running his head off back and forth along the base line and making im- possible gets. He held Hugh to 6—3 in the second set and 6—4 in the third. . “You see,” Hugh told him, * really a better man than I am. a natural-born tennis not. How old are you? “Fighteen—nearly nineteen. g n and vou're You're Jimmy said. . “I'm twenty-three,” Hugh said. “I've played at I ars longer tha vou have and I have to work to beat you.” " Jimmy was still breathing hard; he could feel the sweat running down his cheeks: one knee ached from a spill he had taken on the slippery turf; the grass had stained his white ducks from hip to ankle where he had struck. He glanced at Hugh, immaculate in white flannels, looking as if he had just dressed. “Let's have a shower, *“You'll stay to tea, won't “I'd like to,” Jimmy said, “but I think I'd better be getting on home.” What he really thought was that he couldn’t go to tea in that house in the clothes he had on “Will you come a afternoon?” Hugh asked. 1'd like to,” Jimmy said “I'm playing in a tournament over a1 Brixton on Saturday Hugh ex- plained, “and I want to get in all the practice T can. Would vou care to drive over with me Saturday morn- ing? “I'd like to,” Jimmy said. He tried to remember, walking home, if he had said anything except “I'd like to, 1 afternoo: He could ! have kicked himself for being so inept; and kicked himself again for caring so much whether he was inept or not. Why was it people with money made vou so self-conscious It wasn't the money, reall It was the things that came from always having money. It was manners Huzh wasn't a snob. | Or if he was a snob he was too much of a snob to show it. Jimmy wished | fervently that he had never met Hugh Wainwright, and thanked his stars that he had. The devilish part of it | was he liked the man and wanted to please him Jimmy played next three afternoons, manag time to decline tea. On morning Hugh called for drove him over to Brixton Hugh said in tomorrow at Round Hill the| inz each Saturday him It proved to be an important day in Jimmy's | dea life. It was the day he got h of the sporting thing UGH PREEE Sharp, in Sharp took happened to draw rival, a man the preliminary th first set at 11—9. Hugh took the second at 11—9. By that time the zallery was intensely | interested and Jimmy wanted to vell| every time Hugh made a placement. Hugh broke through in the ninth | game of the third and final set. The | score stood 5—4 in his favor and he | was serving. Twice he aced Sharp. The points stood at 30-love. And then a linesman made one of those incred- | ible decisions that are the despair of | tournament players. He called Hugh's | shot in when it was out. The gallery | groaned. Tne points stood at 40-love. If| Hugh took one more point he would | win the game, the set and the match. | He deliberately served a double fault. The gallery clapped discreetly. Where. upon Hugh served another double fault, The gallery cheered. Sharp saw his chance and took it manfully. He drove Hugh's next service with all he had, passed Hugh at the net, and the points were deuce. Sharp pro- ceeded to run out not only the next | two points, but the next two games. IHe won the match, 11—9, 9—11, 7—5. Jimmy was bitterly disappointed and intensely admiring. “You should have given him two points,” he said to Hugh on the way back to Deep Harbor.” “I shouldn't have let him beat me, h said. e you gave him two points,” Jimmy cried. “I had to give him two to even it up,” Hugh said. “It was the only sporting thing to do.” P immy stole glances at Hugh's face his only named round | Hugh, and THE SUNDAY STAR, WASHINGTON The Sporting Thing to Do | BY LUCIAN CARY. had done that day, and do it quie.ly and easily, asking no reward except his own knowledse that he had done what he called the sporting thing. Jimmy wanted to be like that—iike Hugh. He would be like that. “I'll get my revonge in about three weeks,” Hugh sald. “I'm going to coach you to beat Sharp and then let you onter the Stamford tournament.” It can't be done,” Jimmy said. u're better than vou think you Hugh told him. “Only you don't ¥ your best zame against me.” “I know I don't,” Jimmy admitted. “It's what they 1 a mental hazard in golf. You'll get over it. Neither of them said a word for the rest of that hour's drive. But Jimmy's mind was busy. He thought he had a long way to go to be the kind of man he wanted to be. He was still think- ing when Hugh swung the roadster through the gates at Round Hill and up the drive, and to a sudden jolting stop to avoid running into a girl on horseback. “AVhy, hello. Cynthia!” I “Where did you come from Jimmy ceased entirely to think. just looked. <h* said te For vears afterward he could recall =very detail of that pic- ture whenever he wished to—ani often when he didn't wish to; often when he tried not to. She was’ he saw, a vear or two younger than he was—a girl straight and slim and strong, who sat her hors2 as it she belonged there; a g without a hat, in a white blouse and white cord breeches, and boots of that mahogany color good leather takes, and small silver spurs; a girl who looked straight at you out of singu larly clear biue eyes and smiled with | complete, warm friendliness. Jimmy beinz knew introduc vaguely that he was d: that he was a knowledging the introduction: that he | | must stop staring. He couldn't stop staring. He stared at the horse. It | was a beautiful little hors2, with a high arching crest and the veins standing out on its neck, and its dark coat shining, and its thin nostrils quivering. It was exactly the kind of horse for such a girl to ride. “Jimmy is staying to tea,” Hugh ex- plained. | “So am L said Cynthia. | “Hurry it up then. You haven't time | to change.” THEY had tea on a veranda, over- | looking a garden with a sundial, and beyond an orchard in which the branches were still black lines—black lines in a delicate pale green mist of new bud and leaf. Every time Jimmy caught himself staring at Cynthia Wainwright he looked out at the orchard. He could not talk. He could only stare and listen. The pitch and | timbre of her voice captivated him. | He learned that she had got home | from school that day and that she | was going abroad with her mother in | a month or less to stay a couple of vears. She would be sailing for Paris about the time he got his diploma from the Deep Harbor High School | and started out in overalls to learn his father's trade by carrying mortar | in a hod. He was thinking how great | the distance was that separated her world from his when she turned and asked him whether he was in school or college. “I'm just finishing my last year in the high school,” he said. | And where are you going to col- | lege?"” Jimmy had an impulse to shock her | by saying, “I'm not going to college— I'm going to carry a hod.” He was himself shocked by what he did | ‘He said, “I am going down to Yale, | to the Sheffield Scientific School, to study architecture.” | She flashed him a quick, interested smile. “I've always wanted to be an archi- tect,” Hugh said. “I've been intending ever since I got out of college to pack up and go to Paris and the Beaux Arts.” * K ok ok ! /hy don't you?"” Cynthia asked. Hugh shrugged his shoulders. *I suppose T don't care enough,” he an- swered. “I'm more interested in horses and tennis.” He turned and addressed Jimmy. “My father was a sportsman,” | he added. | “My father is a stone mason,” Jimmy said. “I've always wanted to be a builder, “That's the difference,” nounced. “You'll do something real— something useful—because you've grown up with the idea. I can’t help | admiring my father's courage. But I can’t say he ever did anything useful, or expected me to.” Afterward, walking home, Jimmy's mood alternated between a queer, nameless despair.and an equally queer nameless happiness. How character tic it was of Hugh.and Cynthia to make him feel that he had an advan- tage because his father his hands! And yet their view of life was so different that their words hard- Iy meant what the same words meant to him. They spoke from the point of view of people who didn’t have to do anything at all. Life asked nothing of Hugh except that he be u gentleman. iis great-grandfather had seen to that. Doing something useful appealed to in a certain mood, as a new Hugh an- “I WISH YOU'D PLAY WITH ME, I THINK I COULD TEACH YOU TO BE_'_.AT ME” . as they sat side by side in the road- ster. He saw that Hugh was the sort of man who would always do what he rl | | by worked with | kind of sport. Jimmy had to earn his living, And now he had to earn his through college How absurd it was to let himself in for that because he liked a girl and | wanted to impress her! A girl he didn’t know anygthing about, a girl he had seen for an®hour and wasn't like- to see again more than once or twice before she sailed for Europe and out of his life forever. And yet he did know something about her. e knew everything about her. He knew that she made every other girl he had ever known scem pale or crude or silly. He had known a girl in the high hool who had vitality—and a volce like a buzz saw. He had known u industrious girl who got 99 in . He had known a gi v &y and vivaclous, but had u weak, ill-made body and the mind of u cana bird. Of course, Cynthia had every possible advantage, being a Wuin- wright. That had given her her polse. EE i IMMY, going to ay * sleep that night, | 1w that he must not try to know her. That way led only to a painful defeat, a defeat without a chance to fight. He quietly resolved never to see her again. So in the next three weeks he saw | her nearly every day. He continued to | Play tennis with Hugh and she was al- | ways there at tea. His game Improved. | > did beat Sharp in the semi-finals at | mtord, a long, hard five-set match, in which sheer stubborn stamina pulled him through. He lost to Hugh in him back to Round It was a day in May, veet and still as Sum: |mer, with the apple trees in full| |bloom. It seemed to Jimmy, sitting| |on the veranda, looking out on the orchard, unendurably beautiful. He wondered, sitting there at tea with Hugh and Cynthia. if all true beauty were like that—if it hurt. And then Wiggin called Hugh to the telephone and he was alone with Cynthia. He stole a glance af her. She caught him looking at her and smiled faintly. He had the strange notion that she knew he loved her. But how could she? He had the still stranger notion t she loved him. Which was, of course, absurd. For a brief moment it seemed to him as if, with- |out ever saving a word, they had completely confessed themselves to each other—that each knew the other’s heart—and that this was love, Then she spoke and Jimmy returned to earth. “Jimm to New mother. do on Tuesd He rose to his feet, took two steps toward her. “I know,” he &0 home now. vou again She did stood up rd. ou always go home by the road— don’t you, Jimmy?" |as warm and s she said, “I'm going in York tomorrow to meet We have some shopping to Menday. We're sailing on aid, “and I've got to 1 suppose I shan’t see not and answer directly. looked out at She the “You nezdn’t I'll show it to you She led the way around the house. Jimmy saw an avenue of gnarled »id apvle trees that marked what had once been a farm road leading away from the older part of the house. Cynthia paused and pointed and as she pointed her shoulder touched his. You go through the lane and you come out in a pasture and from there vou &an see vour way down to the village across the fields I see,” Jimm id. He couldn't have said another word. The touch of her shoulder against his made him’ di He tried to think of words in which to say good-bye. He wondered if it would be proper to ake hands with her. He decided it would. Of course would. He turned to look at her., Her cheek was faintly flushed, luminous. Her eyes were pools, clear, dark, deep. Her eyes contained depth after depth. He could not look into her eves. Without a side down apple trees, a better wa; it word they walked side the lane, between the on turf flecked with sun- light, through air scented with apple blossom. Jimmy slowly got control of himself, recalled his mind to earth. | When they got to the end of the lane he would turn, shake hands with | her, say good-bye and go. She would understand everything—that he liked her a lot and that he wished she were not going away, and all that. * ok k¥ |"THEY paused, as if by mutual un- derstanding, at the end of the lane. They could see the village— white houses in a thin line along the | shore, and the harbor, and the point, reaching out into the sound. They stood there, side by side, looking at the water. Then Jimmy turned and held out his hand and looked into her éves, and she looked back into his. Quite slowly, quite deliberately, he held her in his arms. He kissed her. For a_moment he held her close, so close he could feel her heart beat. “I love you," he said gravely. “Yes,” she said. “I love you.” He released her, took one last, long look at her and ran down the hill, across the pasture. There, climbing the stone wall, he stopped and looked back. He saw far off, nearly hidden in the apple trees, the flutter of her white frock. The only sporting thing to do, he told himself that night, was to pre- tend it had never happened. He would not write to her. He might » her if he did. It was inex- ble to have taken advantage of ssing feeling, which she was too young to understand. But nobody need ever know that it had happened except himself and herself. She would forget about it, or remember it only as an episode. His resolution not to write to her was shaken, but not broken, two days | later, when, in a square envelope, he got a photograph. It was a piclura of her on the Arab horse, alniost pre- clsely as he had first seen her, as he would always remember her. The way to forget her was to go to work, to earn his own way through colleze,” to become an_ architect. Tt did not occur to him that doing that Was u way of remembering her. Jimmy worked eight hours a day all Summer carrying a hod, and four hours every night studying for his entrance examinations. He went down to New Haven in September with money In his pocket, passed his examinations and found Jjobs by which he could earn his board and room. By Spring he had man-| aged the task_of earning his living | so well that h could play tennis for 4 couple of hours every afternoon. As a freshman he wasn't eligible for the team. The next Summer he got $6 a day as a mason. In the Fall he went back to college with a| certain grim confidence. He knew | now what a long way he had to go. Three more years In college would permit him to look for a job as a| draftsman in some big office. Five vears as a draftsman—perhaps six years—and he would be ready to practice his profession. He meant to graduate with honors, so that there would be no question about the draftsman’s job in the big office. He graduated in the Spring of 1917 into an officers’ training camp. Sight months later he was in France. It was four years since he had seen Cynthia; nearly three years since he had last heard from Hugh. He only knew they were somewhere in Eu- rope. He was lucky to get a place as a draftsman in the Chicago office of Morrill & Morrill at $50 a week. * % % % FTER six months in the drafting room, Jimmy took stock of what he had done. In the first place, the mem- ory of Cynthia Wainwright was too| much a part of his life. It was mor- bid thus to remember a girl he had neither seen nor heard from in vears; would probably never see nor hear from again. He would cut that mem- ory out of his mind. In the second place, he would need something to take her place in his mind. There would be another girl—eventually. But in the meantime he was going to study skyscrapers on his own. His days were occupied with almost me- chanical work. But his evenings neednt be. He would study modern steel construction. And somewhere in that study he would find the way in which a skyscraper ought to grow to be true to its own nature. For three years, Jimmy manipulat. | ed a T-square in the daytime and studied at night. And then he read| the announcement of a $50,000 prize | offered in New York for the design| of a new hotel, a hotel 31 storles high, and conforming to the new law which forces a facade to step back from the street as it rises. He decided, know- ing what it meant, to win that prize. He did win it. He won it after a vear's intense struggle, a year of working 12 and 14 hours a day, a year when the idea of his building never left him until he went to sleep at night, and came into his head as he awoke in the morning. He found himself in New York again, in Spring, with money in the bank, and fame to his name, and the joy of knowing that the hard-rock men were already blasing into the Island of Manhattan for the foundations of his dream—a | dream 31 stories high and solid as a | mountain. | He was going to look up Hugh Wainwright. He wondered whom Cynthia had married. He wondered if it really mattered to him that he had succeeded, 10 years after. * % K K E ran into Hugh in Forty-fourth reet, two days after his arrival. I wish I'd kept in touch with you, Hugh said, as they shook hands. “Why didn't you answer my last let- ters?” Jimmy stammered. He couldn't tell Hugh why. “Never mind,” Hugh said. “You're here now. You're coming to lunch with me. And after that you're going to Round Hill and play tennis with me again. And after that I am going to talk you into going into partner- ship with me—if T can.” Jimmy grinned. You haven't made any definite ar- rangement with anybody vet, have you?” Hugh asked anxiously. “No,” Jimmy said. “I've only been fn New York two days. Nobody has asked me.” “But they will,” Hugh said. “You can have anything you want now.” Jimmy grinned. He was afraid he looked red. You can, you know,” Hugh insist- ed. “Anything—anything at all.” Jimmy, irrelevantly, wanted to ask him where Cynthia was, whom she had married. But he did not. Instead he went to lunch with Hugh and talked. Hugh had gone to the Beaux Arts for two years. And then he had been drawn into the war. Now he wanted to found an architectural firm. He had connections, opportuni- ties—a bonanza. Later, at Round Hill, Hugh beat Jimmy at tennis in straight sets. Hugh shook his head over that. “T don't_understand it,” he said to Jimmy. “You're really out of my class.” You ought to give me at least 15 points. You're a better player than 1 am. But I still beat you.” Jimmy flushed. He knew why it was that Hugh beat him, would al- ways beat him. It was because he felt, would always feel, inferior to Hugh. But he could not bring himself to say so. “It's that same old mental hazard,” Hugh continued. “It's what they call a complex. Have you got a Wain- wright complex, Jimmy?" “I—I certainly have,” Jimmy said. “But how can you have—now? “T don't know,” Jimmy eaid. “I just have it—that's all.” Hugh shrugged his shoulders. “Well,” he said, “Cynthia is coming back in a week or two. She'll get you out of it." Jimmy took a deep breath. “I'd like awfully to see her again,” he said coolly. . “'She has always been interested in you,” Hugh said. I got a cable from her about you the other day. “What?" Jimmy cried. “She had read that you had won the Shelbourne prize with your design and she was very happy about it ““That’s awfully nice of her,” Jimmy said. He wondered if he could control him- self as well when he stood face to face D. C, MAY 2 uld You Be Willing to Let the Thing Which Means Most to You Turn on a Game of Tennis? “Who,” he asked calmly, “did Cynthia marry?” She hasn't married,” said Hugh. * k% % IMMY sat, two weeks later, on the veranda talking to Hugh and Cynthia. He wasn't aware that she had changed—it was so like that day 10 years earlier. She had changed, of course. She was 10 years older. She was a woman. He wondered if she re- membered that last day—that walk down the lane between the apple trees. He knew she did remember it. But he wanted to make sure. He want- ed her to say she did. And meanwhile they gossiped about things that didn’t matter. “I think,” she said suddenly, “that I'd like to see what the old place is like before it's dark.” She rose and looked out orchard. You may come with me, Jimmy," e said. Jimmy saw again the avenue of gnarled old apple trees that marked what had once been a farm road lead- ing away from the older part of the house. Cynthia paused and pointed, and as pointed her shoulder touched his. ‘The old trees are still there, said. “I see,” Jimmy said. He couldn’t have said another word. The touch of her shoulder against his made him dizzy. He tried to think of words in which to say what he felt. He wondered if he might take her hand in his. He knew he could. Of course he could. He turned to look at her. - Her cheek was faintly flushed, lumi- nous. Her eyves were pools, clear, dark, deep. Her eyes contained depth after depth. He could not look into her eyes. Without a word they walked down the lane, between the apple trees, on turf flecked with sunlight, through air scented with apple blossoms. She must know he loved her, had alway: loved her. She must love him, or she was punishing him cruelly. They paused, as if by mutual under- standing, at the end of the lane. They could see the village—white houses in a thin line along the shore, and the harbor, and the point reaching out into the sound. by side, looking at the water. Then Jimmy turned and looked into her eves and she looked back into his. Quite slowly, quite deliberately, he took her In his arms. He kissed her. For a moment he held her close, so close he could feel her heart beat. “I love you,” he said, gravely. “I've ved you for 10 years.” Yes,” she sald. “And you over the sh 1o still | don’t know that I love you.” He decided that night that the only sporting thing to do was to tell Hugh that he was in love with Cynthia. It was Hugh's right to know, to object. He told Hugh the next day. Hugh listened, frowning a little, his eyes narrowed. Well,” he said, when Jimmy had finished, “what do you want me to “I want you—to approve, I sup- pose,” Jimmy said. “H'm-m!" said Hugh, and paused, while Jimmy waited. “T'll have to be frank with yvou, Jimm he said, finally. 1 want you to be,” Jimmy said. Your father was a stonemason—a | man who worked with his hands.” Yes,” Jimmy said. “And vou have made yourself an | architect—I'm not sure vou aren't go- ing to be the best archifect in Amer- ica, the one whose work will endure They stood there, side | 1925—PART 5. longest. You don't need to ask odds | of anybody. And yet, somehow. vou Somehow you're afraid of me. ‘ve got some complex about me about Cynthia. It shows when we play tennis. You're a better man than I am on a court. But I beat you It's as if you felt inferior. “It's the one thing I've got against you. If it weren't for that I'd say marry Cynthia—there's no man Jiving | I'd rather have for a brother-in-law But you'll never make her happy | when ‘you feel that way inside. You can’t. You've got to get over it. “I know,” Jimmy said, quietly. “We're both entered in the tourna- ment over at Stamford, aren't we?" Hugh asked “Yes,” Jimmy said. “We'll meet in the semi-finals if we | aren’t drawn against each other soon er than that? “Yes,” Jimmy said. “All right,” Hugh in that match and gladly “Beat me yours- aid. she is * IMMY talked to Cynthia that night “I told Hugh that I wanted marry you,” he said Cynthia looked 2t him. She had a | little eager, expectant look, as if she hung on his words, that gave him a \ most delicious sense of power. “Hugh said he had no objection pro- vided I beat him at tennis this week- end.” Cynthia la ighed. “As if he had anything to about us!” | “I agreed,” Jimmy said stolidly. “You agreed?” she cried. | “Yes,” Jimmy sald. And he | spoke it seemed to him that her eves, | so tender, so deep. revealing depth | on depth, had turned hard and cold. | She stood tense, angry, hurt “Are you serfous?” she asked her in smb THEY PAUSED AS IF BY MUTUAL UNDERSTANDING AT THE END OF THE LANE. | sleep. | He had been The Her shoulders dr cre very tired ught vou loved me vou.” ou tension went out of If he were half & man he would go oped, as [ out to Round Hill and carry her off- | like your Lochinvar she said.| Jimmy walked out on the court with a tight smile. Hugh had won the toss. Do you | He had chosen to serve. Jimmy stood | just inside his own base line—which | meant that he was going to take | Hugh's service on the rising bound. " He saw Hugh toss the ball, saw his racket swinging, marked the slice, saw | the ball coming, saw Hugh running lin. He could lob, of course. But he | didn’t. He did what he had never | been able to do against Hugh before He hit the ball with everything he had. The ball shot down the side line, flat and fast. passed Hugh, { struck just inside the backhand slam. She was gone. {ner. Jimmy had taken the chance He walked down to the village and [and won. He took the match in sat in the station for an hour waiting | straight sets for a train to New York. He got out| Hugh came rur it the G nd Central and walked after that lust sizzling drive cross- walked to the end of the park and rt to shake hands. Jimmy saw back. He hated her. He loved her. that he was glad. For a fraction of Was there any difference second Jimmy shrank from that % % ok % ke, from the thing he had to amazement her body if she w “I th “1 do love o say love me. think if you really loved me vou'd let it turn on a tennis match? “But you don’t understand.” Jimmy said bitterly. “You aren't letting me explain.” “1 do understand—now.’ “I thought—I thought you all these years—just I had. T thought—oh, I don't know what I th t ; he went -quickly into the hl;\l.‘“J Jimmy started after her. And then he | stopped. He heard a distant said. 1d cared she ‘ door co: inz toward the net 1 he smiled to himself. He went to rooms and tried to |y ser id. His Wain- sleep. After a long time he did |y When he awoke the thing was | pler. He saw what she wanted. | She wanted what every woman want- | eye ed. She wanted to be won: more, t0 | tim, be taken, regardless. He hadn't done |and easily it. He hudn't even said the thing: Enow e he had wanted to say. He hadn't told were m her what she had meant to him th afternoon.” 10 years. He hadn't made love u mean vou eloped?” —really. He hadn't let go—as Jimmy said quiet] were 4 man and she were fraid to. He had been | “After I'd said afraid of her he had al-| peat ways been. And now he had lost her | thi, —unless he could find some way to| let her know how much he loved her. | No—not let her know—make her feel He must make her feel that he want €d her, that he was goinz to have her. | my?" he aske hat nothing could stop him ‘she’s yours looked Hugh straight in the shook hands. For the first life he felt quite simply Hugh's equal is, Husgh," he said ied in Brixton yester Jimm; s he “we 1 wanted tennis first—after you to as much as every- g 1 “Yes,” Hugh gain said. Iy held out his hand ke hands again, Jim- Days of Week and Hours of Day Tested for Varying Mental Powers BY CARL SHOUP. HERE was a day when the effi- ciency expert bloomed in the land, telling everybody how to do everything with the least possible trouble and the great- est possible saving. But there was a very important quystion which he and his tribe left untouched, and that question has at last been tackled by sclentists in a thoroughly systematic manner. It is, in brief, average man, in as follows: Does the the long run, do bet- ter work on any one day of the week than he does on other days? Is Sun- day a better day than Thursday? Can you get more done on Tuesday than you can on Friday? Again, is there any one hour of the day at which the mind is the most active? 1Is 10 o'clock at night better for mental activity than 4 o'clock in the afternoon? Can we accomplish more around 9 o’clock in the morning than we can around 9 o'clock in the evening? In place of guesswork, Dr. Donald Laird and his assistants in a series of interesting experiments in the psy chological laboratory of Colgate Uni- versity, have used systematic tests with numerous college students. Un- covering many facts hitherto un- known, they have found, among va- rious things, the tests indicate that: 1. The average mind works at its highest pitch on Wednesdays, with its low mark on Saturdays. The hour at which the most can be accomplished is 8 o'clock in*the morning; the poorest hour for work is 4 in the afternoon. It must be admitted that Dr. Laird was embarking on an uncharted sea when he started out to discover the answers to those questions propound- ed above. How could he find the an- swers? A correct method of testing was absolutely necessary, else the final statistics would be unrelfable and 2 nap MM TUES WD TR Fm st 18] ” Above—Chart showing average efficicney, on each of the seven days of the week, of 112 university students during six weeks' system. atieally formulated tests. Relow—Chart of hours showing -that the ave student mentality was sharpest at 8 A, M., and dullext at 4 P M. oAM__oAm_iem arn with Cynthia. He wondered if he would have any of the same feeling he had ence had about her. | tution, the conclusions worthless. What kind | of tests, then, should he employ? Without doubt, mathematical | problems are helpful in estimating in telligence. Dr. Laird. therefore, de cided to put them on the list. He se- lected two types—simple one-column | addition and more difficult two-column® addition. Comprehension tests—the “What wrong with this room?” type of prob- lems is somewhat of an example—are valuable to the psychologist. One tes of this kind was therefore used. i Dr. Laird then decided that he| would place special emphasis on mem.- | ory, as that is a phase of mental ac- | tivity which is found quite necessary in evervday life. He put four types of memory exercises on his program. This made seven different kinds of mental tests. To round out the list fully he added an exercise in substi. rearranging letters that had been purposely jumbled up—and one | in reading time, the reading being of a piece selected for memorization at the same time. Now came the problem of selecting the subjects to be tested. As he was doing his work at Colgate Universit: Dr. Laird decided that it would be best to use college students, as he could get enough to make the test of some value, and the regularity of | their appearance could be counted on. | He selected 112 students, and from that number made 7 squads of 16 each. The intelligence scores of these groups, as determined by pre- vious comprehensive tests, were approximately equal. Thus he had good material with which to start on his quest of the mental “high spots” and “low spots” of| the day and week. There was oné point, howevel which might have rendered all his work of little value had he overlooked it. That was the mental attitude of the students. If they knew the direct object of these tests, might they not, consciously or unconsciously, be influ- enced in their reactions by their owr set opinions? If student A had a firm supersti- tion that Friday was the high spot of the week, he might be strongly influ- enced by such a feeling, should he know that the tests were being made to see whether or not that supersti- tion were actually true. So the canny psychologist “fogged” the 112 by tell- ing them that the work was being done in connection with effects of temperature changes. The start was made, and for six weeks the work went on smoothly and steadily. The whole battery of nine different tests were fired at the vari- ous groups at 8 and 10 o'clock in the morning, and at 1 and 4 in the after- noon, and at 8, 9 and 10 at night. This was done consistently eves the end of the six weeks' period Dr. Laird expressed himself as satisfied that enough data had been gathered to make some valuable deductions, so the students were released from their extra mental duty. Not one of the 112 had missed a single test period— the records were complete. Then followed computation of the result. Statistic lovers may be interested to learn that 4,704 test blanks had been mimeographed and scored, 17,000 numbers had to be added to tabulate the records, 20,000 numbers had to be squared, there were 53,000 subtrac- tions to be made, and all the computa- tions had to be checked. It was no light job that Dr. Laird and his as- sistants had undertaken. The results, however, were clear is | that day | found to be the hour when the aver- and definite enough to be well worth | difficult additi the labor invoived idly at this time than at any other. On the average, Wednesday stood | Just why this should be so, Dr. Laird well above the rest of the week. It |does not attempt to explain. got first place in five of the nine tests, | Indeed, he does not try to deduce nd although it made a poor showing |any special theory from his work at in the addition und comprehension |all. 1le has conducted the tests on a tests, its average was quite a bit above | scientific basis, he has tabulated the ¥, which finished in second |resuits, and shows them to the world plice. for what they may be worth. The im- The stud portance of his achievement lies in tal work on the fact that his is evidently the first battle for cellar position between Sat- |test of its kind to be made so thor- urday and Sunday, but when the oughly. The fact that his work has smoke cleared Saturday was resting | given clear-cut results lends color to on the bottom. the hope that we may soon know far One cur thing was that the best | more about our weekly and daily work on both of the addition tests | cycles of mental activity than it was was done on Tuesday. So, if you have |ever deemed possible to ascertain. a difficult mathematical problem to | e untangle, you might do well to pick | Seeing “Invisible” Light UCH as man instead of Wednesday. The most erratic of days was Mon- | |\ en i airon his ability to see, his eyes are sensitive to on day. At one time or another among the nine tests it occupied every posi- e E a o very small portion memory work—the low marks for the | “onstantly flooding the world. students in three of the memory tests were found to be on Monda No less interesting were the re- ults when work done at different hours of the day was computed. Eight o'clock in the morning was ons were done more rap- nts did their poor aturday. It was a men lose Visible light, ranging from the deep violet with wave-length of sixteen- | millionths of an inch to deep red with a wavelength of twenty-eight mil lionths of un inch, occuples only an o tave of the spectrum of ether vibra tions. Our eyes tell us what materials e opaque and translucent to visible light. Shorter than visible light are the ultra-violet rays with wave-lengths from one-millionth _to sixteen-mil- | lionths of an inch. These rays affect { photographic plates markedly and, in fact, much of the image in ordinary negatives is due to these rays which cannot be seen by the eve. They have also been found to affect the growth and health of man, animals and plants. The sun's radiation is rich in these ! rays, and light from mercury vapor lamps in fused quartz containers con tains much of these wave-lengths Most materials opaque to visible light are also barriers to ultra-violet light, vet ordinary window glass will not let it through. The minerals fluorspar, quartz and rock salt are transparent to ultra-violet. These rays also have the property of making some substan- jces, finger nails for instance, glow with visible light. The shortest waves known to man are the gamma rays of radium, given off when this wonderful chemical ele- ment spontaneously disintegrates. These are even shorter than the hard X-rays used medically in the treat- ment of cancers and tumors and in scientific_work. Rays from and the ¥-ray rays impinge on solid very penetrating, passing through skin and flesh and many other substances. By allowing them to strike fluorescent screens they can be made visible to the eve and they can also be per manently recorded on photographic plates. age student mentality was sharpest. It had a decisive lead over 10 a.m. which showed up next best. The men- tal power of the students apparently | diminished steadily through the morn- ing and afternoon, until at 4 p.m. it reached its low mark. There was a noticeable pick-up from then on, and 9 p.m., surprisingly enough, was a better hour than $ p.m. After 9 o'clock, however, a decline set in again, and the day's tests closed at 10 p.m., very near the low mark of 4 o'clock. It will be remembered that mathematics tests had a special d Tuesday—on which the best results were obtained. Likewise, in compar- ing the different hours of the day, it was found that mathematics had a special hour all its own. This hour was 1 o'clock—both the simple and the ay: = 1P 5 200 Patents Daily. R]‘IPURTS of the Patent Office for 1924 show that applications were received at the rate of about 300 a day and that some 200 were granted daily, including designs and trade marks. Those issued totaled 63,062, an in- crease of nearly 6,000 over 1923, and the number of applications was 101,- 134. The office reduced the number of applications awaiting official action by nearly 12,000 and lowered the average time to four and one-half months for new work and to between three and four months for old work. DONALD A. LAIRD, PH. D., ASSO- CIATE PROFESSOR OF PSY- CHOLOGY AT COLGATE UNJ VERSITY.