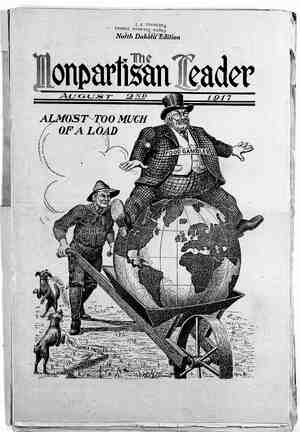

The Nonpartisan Leader Newspaper, August 2, 1917, Page 8

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

‘Growing Flax for Oil and Fiber Present Shortage and Vast Fields Out of Crop Hold Promise for the Northwestern Farmers F FLAX is not to become a g profitable crop for those farmers who are situated in a region where it can be grown well, there is no use in looking back upon the history of past crop years. Since the season of 1911, the price of flax seed has increased steadily in the United States, although the world supply has not been dwind- ling. The government estimate for last season was 15,495,000 bushels of seed, and the July crop estimate for 1917 is that this will be exceeded by 1,600,000 bushels. The United States portion of the total flax seed yield, however, is very small being approximately 10 per cent, in recent years, the world yield of seed being about 130,000,000 bushels for the last seasons for which figures were available. The great war has stopped all chance of securing anything like re- liable figures since the crop of 1914 was harvested in all those countries where flax is principally raised, Russia, Belgium, Bulgaria, Servia, Austria, etc. But though the United States yield is comparatively small in quantity, it is of the finest quality for oil production, s0 valuable in fact that American farmers have not yet taken any serious interest in cultivating it for its fiber. The flax crop of the United States in 1915 had a value on the farms of ap- proximately $24,000,000 with the four hard wheat states leading in its pro- duction and monopolizing almost the whole of that value. These same states in 1911, (which was the greatest flax year ever known in the United States, from a value:point of view) produced a crop valued at- approximately $35,- 000,000 including such minor additions as other mid western states produced, That year the average price paid for the seed was $1.82 per bushel, and the United States production was close to 20,000,000 bushels. BIG FLAX CROP BRINGS GOOD RETURN Basing their judgment upon the good results of that season, the Northwest- ern farmers turned to with a will, and planted the greatest acreage of flax ever known in the country in 1912, namely 2,851,000 acres. With thisg bumper acreage, they produced the biggest yield ever known, exceeding 28,000,000 bushels but at the same time, flax was knocked down ig price to the lowest level of the past 10 years, $1.14, and itg farm value was $3,000,000 less than it was the previous season. The farmers raised almost 9,000,000 bushels more of the seed, and they got $3,000,+ 000 less for it. That put a crimp in flax culture and the following four or five years saw & falling off of 10,000,000 to 15,000,000 bushels annually in the total United States yield.- But prices began to re- cover, and now with the great flax countries at war, and engaged in using up at a tremendous rate, the chief products made from linseed oil, instead of producing the crops from which to manufacture those products, flax promises to come into its own again, and bring to the farmers a good return for its'cultivation. In fact this result is already being seen, for prices gained over four cents the next year after the big drop, gained eight cents more the next year, 47 cents additional the next, and present prices are hovering around $3 per bushel. How long the European and Asiatio flax fields will remain out of produc- tion will depend upon how long the war lasts, and how badly demoralized is agriculture in those countries, It will undoubtedly take time for the peasants of Russia and Austria to catch up with the setback that half cultivation, and wide destruction has wrought. South America produces from 23,000,000 to 40,000,000 bushels of flax seed a year in normal times, while Europe ranges somewhere around an average between those -points, and North America (which means, chiefly Minnesota, Montana and the two Da- kotas) produces from 13,000,000 to 20,- 000,000 bushels. DIFFICULTY OF FLAX CULTURE IN RUSSIA But even with the greatest stimula- tion towards recovery that conditions in Europe will be likely to furnish, the American farmers, and especially. the Northwestern farmers, where flax cul- ture is now best understood and the best linseed oil produced, will be in a position to put on the market a great . amount of the seed under advantages that do not exist-in the old country. Some idea of the difficulties of rais- ing flax in Russia, one of the greatest producers, may be gleamed from the illustrations shown on this page, indi- cating the great economic handicap under which these simple people strive. Cultivation for its fiber is one of the chief uses of flax, and Russia con- tributes to the world’s linen roduction vast quantities of crude flax fiber of many different grades. In extensive areas of Russia the Flax straw in the growing region along the Volga river, showing how it is spread out for “dew retting.” so thin as to dry out. It is afterwards hung up to. dry, and women with woodel paddles,. seated at long low benches, beat and paddle the worthless matter from the stalks, separating in this way the.fibers, PEASANTS GROW IT FOR ITS FIBER £ Sometimes instead of dew retting, Seed flax hung up in the common Russian peasant manner to dry so that the seed can be beaten off before the fiber is put out to “ret.” peasants still follow the old hand meth- ods of production and preparation of their fiber that were used in primitive times. After pulling-it by hand (the best method where -fine staple is to be obtained) the flax straw is laid out carefully on the fields to be rotted or “retted” by the dew. This has to be done with the greatest care in order that there may not be layers of the fiber so thick as to rot to weakness, or The Russian peasant method of marketing homemade bales of flax fiber after retting and beating. the fiber is retted by being stood on end in shallow, warm sloughs, covered with sod and weights and left to steep for two or three weeks. This is a method as old as fiber culture and is widely used where climatic conditions do not favor the dew retting process. It is a modification of this method,-by substituting vats for sloughs, and heat- ing the water, thus cutting down the period of retting from weeks to hours, that has been used in the modern manufacture of linen in France, Bel- gium, Ireland and elsewhere. After the superfluous vegetable mat- ter has been soaked and beaten off of the stalks, the crude fiber is gathered into bales and trundled to market, where a great variety of prices obtains, and where the peasants are forced to accept- buyers’ prices just as wool growers and wheat growers in America are forced to accept the prices estab- lished by the buyers. The whole labor- ious routine of flax culture is broadly hinted at in the accompanying pictures, but the pictures fail to show one pro- cess, which is none the less- arduous. In spite of the fact that much Rus- gian flax is grown for its fiber, the seed is not thrown away. Much of it finds its way into commercial products, and of course vast quantities of the seed must be saved for replanting Russia’s 3,000,000 to 6,000,000 acres every year. The Russian peasants in many parts of the country, still flail out the seed in the old fashioned way, beating small bundles of the straw on large canvass blankets and separating the flax from foreign seeds by hand methods. PAGE EIGHT Thus the Russian peasants are com« peting by hand with American tractors, threshing machines, and up to date cleaning machinery, and their patience and great numbers can not possibly make up#for the better methods avail= wble in this country. A PORTABLE GRANARY A portable granary saves both man and horse at threshing time. It can be moved into the field and the grain run right into it from the machine. Mr. ‘W. R. Porter, superintendent of the North Dakota demonstration farms has had a good deal of experience in using ' portable granaries. He gives the following suggestions for such a building: On ning 4 by 6-inch sills 14 feet long, placed two feet apart, nail a rough board floor 12 by 16 feet, Make the- studding § feet long from 2x4’s. Side with drop siding. Put on a one-third_ _ pitch shingle roof. Lay a matched fir floor, make a trap door in roof. Two men can put up such a granary in two days at a cost of about $75.00. It will hold 1200 bushels of grain. Kept well painted, such granaries have lasted 20 years. Such a granary can be pulled with four horses. The moving <an be made easier by putting “wheels under the sills. Four old threshing machine cyl- inder pullies put on shafts, long enough ‘to reach -across two sills and one placed at each corner will reduce the pull, so that the granary can be move= ed with two horses. POISON THE POTATO BUGS Potato bugs are voracious feedeérs. Parig green or arsenate of lead is a good poison for them. The arsenate of ~ lead is the cheapest to use now and it sticks better than the Parie; green. It comes in dry form and as paste. Make up at the rate of three pounds of paste or one and one-half pounds of the dry arsenate of lead to 50 gal- lons of water. Spray this on the vineg as soon as the young bugs begin to hatch. Use Parils green at the rate of one-half pound to 50 gallons of water and also add three pounds of lime, KEROSENE EMULSION Kerosene emulsion is good for kill~ ing lice and other sucking insects. It Is made by dissolving one-half pound of ‘common soap in one gallon of boil= ing water. Pour this into two gallons of kerosene and stir vigorously so as to mix the kerosene with the soapy, water. ‘When ready to apply, mix one gallon of the solution (which looks somewhat like sour milk) and 10 gal= lons of water. : - STRAW SHEDS Straw sheds can be bullt so as 1o make good winter shelters for live stock, .They can be made warm and they will be well ventilated. A good way to make a straw shed is to put u a frame work on a well drained Spo and cover it with woven wire and then throw straw over it 'when threshing, ‘Walls for keeping out wind can e made out of straw by putting up a double row of posts two to four feet apart, nailing on woven wire and fill~ ing between with straw., Fertilizer for orn fields pays, ace cording to data discovered by the Ohig experiment station: $33.06 per acre fop unfertilized, and $50.73 for fertilized, .