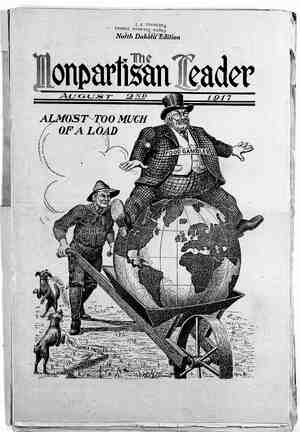

The Nonpartisan Leader Newspaper, August 2, 1917, Page 10

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

e The C_heese and Butter Gam What Wisconsin Farmers Have Been up Against and Some of the Things They Have Done to Help Themselves - Co-operative cold storage plant at BY_.E. B 'FUSSELL (Iirst of two articles on co-operation, in Wisconsin) ISCONSIN farmers produce 125,000,000 pounds of butter a year, one-sixth of the nation’s supply, 235,000,000 pounds of cheese, which is three-fifths of the cheese produced in the United States and enough to fill a freight train 75 miles long. Potatoes, grain, tobacco and sugar beets are other big crops. The farmers are at the mercy of the middlemen just as they are everywhere else. In the case of cheese it has been shown that of every dollar the con- sumer paid for the product, the farmer received only 50 cents. Besides these so-called “legitimate” profits the farmr=- ers have found the middlemen increas- ing their profits by false grading, mar- ket manipulation and other dishonest methods. In some cases farfmers have been driven to go on strike to get anything like fair prices for their products. In the sugar beet section, for instance, there were complaints by farmers that they® were not getting fair tests at the factory, which paid for beets on the basis of their sugar contents. This suspiclon was increased when the sugar factory refused point blank to allow the University of Wisconsin to make tests to check the factory tests. So the farmers just quit growing beets until the factory agreed to buy on a weigh basis instead of buying on their own tests. Tobacco growers similarly were at the mercy of the tobacco trust until the tobacco growers of the south, driven to desperation, rose in their night rider raids. CONDENSERY CONTROLS SOME CO-OPERATIVES Mostly the farmers have attempted some form of marketing co-operation in an effort to eliminate middlemen and correct vicious trade practices. They have been given assistance in this direction by the National Agricul- tural Organization society, an organi- zation largely financed by Sir Horace Plunkett of Ireland, who made millions in cattle in Nebraska in the early days, returning to Ireland to work for land reform and to assist the peasant farm- ers there. The N. A. O. S, as it is called, . has its main headquarters at Madison, which is state headquarters also for the XEquity scciety, also a staunch supporter of co-operation. There are 923 creameries in Wiscon- sin and about half of these are co- “operative enterprises or call them- selves such. Many were organized as jgint stock companies, -with one vote for each share of stock, This allows one person, if he can get control of a majority of stock, to control the en- tire company. It has happened that some of these so-called co-operative companies have become controlled by some of the large centralizing plants of the butter trust, just as some so- called farmers’' elevators have really become nothing better than line ele- vators. In one case recently at Hebron, ‘Wisconsin, one man secured control of a majority of stock in a so-called co- operative creamery and closed it in-the interests of a nearby condensery, thus - forcing the farmers to sell their milk to the . condensery instead of the creamery. Under the new Wisconsin law, how- ever, co-operative enterprises operate under the rule of one vote to a mem- ber, instead of one v0t¥ to a share of stock and stockholders’ profits are limited to 6 or 8 per cent, all above this figure going to producers as pa- tronage dividends. CO-OPERATIVES HAVE A HARD PROBLEM Wisconsin milk producers, have been encouraged to co-operate by the vast middleman’s machinery operating in the state. One milk producer told the writer that six buyers for as many dif- - ferent competing private creameries had visited him one Sunday morning. The expense of theése men naturally is taken out of the price paid for the farmer’s milk, just as the price of six competing delivery wagons, all travel- ing on the same route, is added to the price of the consumer’s milk. Many obstacles are placed in the way of the farmers going into the co- operative game. C. E. Hanson of River Falls, Pierce county, a co-operative center in the western part of Wiscon- sin, told the writer about their experi- ences. “Farmers were only getting 15 to 18 cents for their butter fat from private dealers,” said Mr. Hanson. “We thought we were entitled to more and decided on a co-operative creamery. ‘We went to the proprietor of a private creamery. He told us there was no money in the game and’ offered to sell us his plant, but he named us a price about three times what it was worth! We decided we would have to build a plant of our own. Then he came down and we finally bought at about one- third the price he had named first. “The co-operative plant is paying better than 40 cents for butter fat now. We have never paid less than 25 cents. We sell direct to large grocery stores whenever we can and cut out all the middlemen possible. “We have had the same experience with our co-operative elevators, We are only 45 miles from Minneapolis but when we were selling our barley to the line elevators we got all the way from 15 to 27 cents less than Minne- apolis prices, although the freight rate to Minneapolis is only 6 cents per 100 pounds. Since we built our co-opera- tive elevator we have be&n getting practically all the Dbusiness. There were six private elevators competing with us at the start; there are only two now, and we've got those on the run. . e “Our experience has = encouraged others. There are six co-operative ele- vators 'in the county now and seven . co-operative creameries.- Last year our elevator paid so much better prices for barley than the line elevators that farmers at Spring Valley, 23 -miles- away, hauled. their barley- by wagon to our elevator. . The line elevator at Spring Valley claimed their barley was below grade and offered them only 60 to 70 cents. We paid 90 cents to $1 and had no trouble disposing of this barley. Our elevator has paid -6 per cent on its stoek every year and we have made three or four patronage dividends besides.” 3 CO-OPERATIVE LAUNDRY IN'ONE COMMUNITY At River Falls they have gone so far along co-operative lines that ‘they operate a co-operative laundry to re- lieve farmers’ wives of backbreaking work. They do their potato buying on a co-operative plan, also. ' One of the most notable successes in the way of co-operation in Wiscon- sin is the cheese marketing organiza- tion at Plymouth, Sheboygan county, the center of the cheese district. This organization came mainly as the re- sult of the efforts of one man, Henry Krumrey, a farmer who keeps his eyes open and is watching things all the time. Cheese prices in Wisconsin are fixed by cheese boards. There are six or eight of these boards, each with a limited membership of cheese dealers. They hold meetings and chalk upon a blackboard bids and sales, just as they do in a grain exchange. Less than 10 per cent of the cheese produced in the state is actually sold at these boards, but the board prices are taken by dealers all over the state as the prices to be paid to the cheesemakers. GOOD REASON FOR CHEESE FLUCTUATIONS Cheese prices during the summer of -1911, as fixed by the board, ranged from 11 to 13 cents, and the dealers got the bulk of their supply at these rates. The next winter cheese prices came up as high as 22 cents a pound and the same cheese that went into the coolers at 11 to 13 cents came out Cheese from a co-operative plant awaiting shipment - 'PAGE TEN Plymouth, Wisconsin, owned by Sheboygan county cheese men, with Which they broke the dealer’s grip on the market at these rates. At this time of year the farmers were producing compara= tively little cheese so the increase did- r’'t do them much good. As the sum- mer of 1912 approached the price started 'to drop again, falling back o 15 cents in May and finally dropping three cents in one day. Krumrey had been watching things pretty = closely. The cheese prices looked bad; there is no reason, in the cheese market, for a marked difference ‘between summer and winter prices, as there .is in_the egg market, because cheese, unlike eggs, improves by aging in storage. Krumrey started investigating. He found evidence pointing uynmistakably ‘to a conspiracy among the cheese dealers to depress prices during the summer, when -they were buying cheese, and to raise prices during the winter, when they were selling, Krumne rey found that the Plymouth cheese board, which virtually fixed cheese prices for the whole state, other boards copying their quotations, was a close combine, refusing to admit new mem- bers. He found that in many in- *stances cheesemakers were being paid “on the side” by dealers to bring their cheese to the board and sell it at a low price. For instance, the cheese- maker in question might offer his cheese at the board for 11 cents. He would be paid 2 or 3 cents a pound extra ‘“on the the side” making the real price 13 or 14 cents, but the 11 cent rate would be adopted as the pre- vailing rate for cheese purchases. The dealers called this ‘tipping”. UNIVERSITY LOOKS INTO THE MATTER “Krumrey wrote a series of letters to newspapers exposing these practices of the board. The farmers flocked to his standard. One June day more than a thousand dropped their haying and came from miles around to-Ply= mouth to hear him speak. - The University of Wisconsin sat up and took interest in proceedings. Among farmers in Wisconsin there is considerable criticism of the college of agriculture, a branch of the univere sity at Madison. They say that the college does fine work in teaching the farmer to make two blades of grass grow where one grew before, but that it is paying practically no attention to helping the farmer market either the first blade of grass or the second one. In other words, they say all the col- lege of agriculture work is directed toward increased production and prac- tically none toward better marketing. But in this instance the university, authorities made a thorough investiga- tion. % The university Investigators got right on a tub of cheese and followed it from the maker to the consumer, They found that the farmer got just about half of the price that the cone sumer paid, In the case of American cheese which sold at 25 cents a pound, for instance, the farmer got 13 cents, the cheesemaker got 1 3-4 cents, the dealer 3-4 cent, the railroad 1 1-4 cent, wholesalers and brokers got 2 cents, storage and shrinkage cost was 3-4 cent and the retailer got § 1-2 cents. In the case of limburger cheege therq ‘was even a greater “spread” In thid case the farmer got only 11 cents, while the retail price was 26 1-2 cents, This was with comparatively hormal ¢ [ —