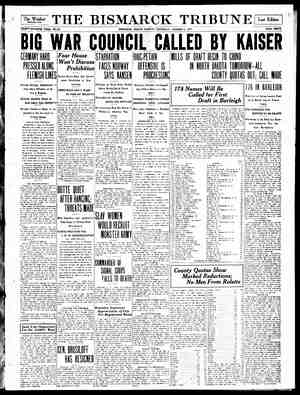

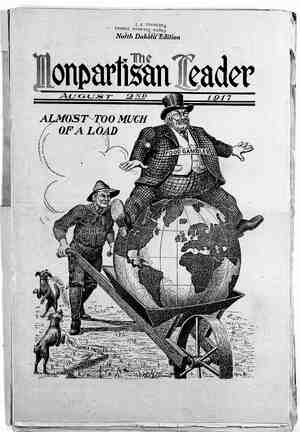

The Nonpartisan Leader Newspaper, August 2, 1917, Page 5

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

N S s e e Olaf Sjodin’s Food Factory ' How it Compares With Other Factories and Something About the Need for Organization of the Farmers BY N. S. RANDALL LAF Sjodin is one of Amer- ica’s ‘most important manu- facturers. Fourteen years ago, Olaf came to America from Sweden and settled Bbout one mile south of the village of Opsalla, Morrison county, Minn., and began his American career as a pro- ducer of food. \ Many have been the hardships en- dured while Olaf has been struggling to make his business a paying one. Year after year has seen him just on the border of bankruptcy but year after year by indomitable will has he held on and on, hoping against hope that by some fortunate circumstance he might achieve the independence that he has seen come to others that struggled not -nearly as hard or as long, only to conclude, after. fourteen years, that his business has not been conducted on the right plan and that, before he can possibly hope for the independence that has heen the idol of his dreams he must reconstruct the whole process of production. It has taken years of bitter experi- ence to bring Olaf to see the necessity of this important move. Without com- petent counsel or advisors among those engaged in like business with him he has gone on blindly trudging away, no hour too early for him to be at his task; no hour too late for him to be still found at it—and by dint of living a meager life and conserving every possible resource he has reared his little brood and provided as best he could out of. the little that was left him after he had paid the tribute exacted of him by those whom he must needs pay tribute to in order to continue at the task of feeding the world. HEARD ABOUT LEAGUE; SAW GREAT LIGHT I say that Olaf is one of America's most important ' manufacturers be- cause Olaf, like the test of the thou- sands of farmers in Minnesota, is try- ing his best to feed the world and at the same time save enough out of what he produces to feed and clothe himself. 'He has succeeded wonder- fully well with the former task, but not so well with the latter, for while he has been obliged to skimp and save that he and his family may live, those to whom he has been compelled to pay tribute have fared sumptuously. " But Olaf has seen a great light. He saw its first gleamings when an or- ganizer for the sat at his table and showed him where he was running his business at a loss; all because he had failed to take ad- vantage of his opportunities by doing Just as every other business man en- gaged in every other business except his had done, and that is to organize his business together with the busi- ness of every other food producer like him and thereby place himself in the position of those to whom he has been paying tribute all these years—in the position where he will have something to say in setting the price he sells hig product for. Strange, is it not, that an industry of such magnitude as the farming in- dustry, which is the largest single in- dustry in the United States in_ the amount of capital invested, in land ~ and ‘the machinery and stock neces- sary to operate, should continue to be such a poor paying business when Nonpartisan league . many other industries of lesser im- portance have flourished? But it is not so strange when you analyze the conditions under which the farmer is compelled to do business and a true way to analyze it is to compare the advantages afforded every other in- dustry with the disadvantage of the food-producing industry and it was this analysis that revealed to Olaf Sjodin the true condition of his busi- ness and what is true of Sjodin’s busi- ness is also true of the farming in- dustry everywhere. AFTER FOURTEEN YEARS, NO RESERVE SAVED It was Olaf himself who assisted the writer to arrive at the figures I am about to give you, relating to the amount of money he has invested in his business in land and the machin-~ ery and stock necessary to operate his farm. First of all, Olaf has 100 acres of land which he values at $100 per acre, including the buildings, This land was a forest and much of it covered with rocks when Olaf came here fourteen years ago. It was Olaf who cut the trees, carted away the rock and worked in the woods cutting railroad ties with which to make his first pay- ment on his farm. A portable sawmill cut the lumber from his forest, out of which he gave to the sawmill owner enough lumber to build five houses, that Olaf might have enough with which to build one house. Fourteen years of incessant toil have made Olaf an old man long before his time and in all that time there has been nothing stored up against the day when he can no longer go to the fields. The $10,000 of land value, together with the machinery and stock, brings his' total investment up to $11,537. With this amount of capital we are ~ PAGE FIVE Olaf Sjodin's factory hands. Olaf Sjodin, League organizer. now ready to engage in the business ‘of farming. We open a set of books and proceed like every other business does to keep account of our trans- actions, to know at the end of' the year just:- how much we have made or lost during that time. SR First, we conclude that if Olaf did not have his money invested in land and machinery he could invest it in a mortgage as the banker does, and without a stroke of work that money would earn, at T per cent, the sum of $807.59. This amount must be charged against the farm. 3 FIXED CHARGES IN. CONDUCTING FARM Charging taxes the same as last year, we have $62 also to charge up. Next comes insurance, which was $10. His seed this year he estimates as worth $400. We estimate the wear and tear of his horses and machinery at 10 per cent, for it is safe to say that every ten years such tools must be replaced; this makes $153.70 the farm must earn to be even with the game on ‘wear and tear. : Olaf says he would be satisfied to work for $2 per day straight through, winter and summer. This is $730 for labor, to which must be added a man for four months at $40 per month, which makes another ‘$160,' or a total labor cost of $890. As every other business is figured, we must expect Olaf’s farm to at least repay the cost of which in this case is the sum of -$2,313.29, In other words, $2,313.29 is the cost to produce whatever Olaf may be able to force the farm to pro- duce, but that is an unknown quan- operation, . tity. Olaf has to take chances on heat, rain, hail, wind, rust, blight, bugs, worms and, worst of all, he does not know in advance whether he will get a price for his product that will pay the cost of producing, to say nothing of paying anything for PROFIT. COMPARING THE FARM WITH THE FACTORY Having arrived at a comprehensive idea of the cost of producing an un- known quantity of food, let us direct our attention to most any other busi- ness with an equal amount of capital invested, and ascertain the method by which it is operated. Suppose we take the man who makes chairs. The Johnson Chair company is an exclusive manufacturer of chairs. The capital invested in plant and machinery is the same as Olaf’s, and the same interest ' charges must be charged up to the expense of the busi- ness, together with taxes, insurance, light, heat, power, labor and deprecia- tion. To which we add the cost of the raw material. We now have the cost of production, the same as in Olaf’s case. But unlike Olaf, we. know ex- actly the capacity of the plant to pro- duce chairs and we can tell almost to a chair what the year’s output will be. \If the cost of operation of a chair fac- tory was the same as the cost of oper=- ation of Olaf’s farm, the proprietor of the chair factory would reason about like this: “My operating cost is $2,313.29. T am entitled to a profit of 26 per cent, so my selling cost will have to be $2,891.61. But, to be safe, I will place my selling cost at an even $3,000. Now, my factory can- produce 600 chairs a month, or 6,000 chairs per year. I must sell my chairs at 60 cents apiece.” The chair manufacturer has the power to set the price and Olaf hag not. Why? WHOLESALER AND RETAILER SET PRICE Next, Olaf wants to buy a chair. He has sat on soap boxes and benches for years with never a chance to rest his back except when he sat in the easy chair in the banker’s office when he was signing notes for borrowed money. So Olaf goes to the retail fur- niture man and asks the price of chairs. The retail man says (to him- self, of course): “Let me see; these chairs cost 50 cents apiece; freight, 2 cents; clerk hire, rent, light, heat, insurance, and MY PROFIT will bring the price up to $1. The price is $1, Olaf.” 8o Olaf buys a chair and in buying it he pays the cost of the raw material, cost of everything that enters into the cost of production and the cost of freight and the cost of everything that enters into the selling of it, plus TWO PROFITS. Why? - By agreement, the Chair Manufac- turers’ association says chairs are 50 cents wholesale, By agreement the Retail Furniture Dealers’ assoclation says chairs are $1 retail: They both say so and it must be so, and Olaf pays it. I have compared the manufacture of chairs with the _manufacture of (Continued on page 16) - W { i [ }; { !