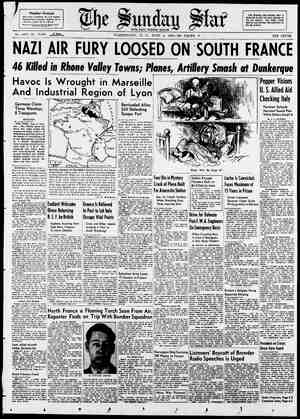

Evening Star Newspaper, June 2, 1940, Page 35

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

THE SUNDAY STAR, WASHINGTON, D. C, JUNE 2, 1940—PART TWO. c—=3 - U.S. Armed F (_)rces,’After Years of Want, Rush to Expand Air Defenses Suggested Plans of Correcting Aerial Deficiency Vary Greatly Army and Navy Combined Now Possess Only 2,707 Fighting Planes, Many of Which Are Obsolete By Richard L. Stokes. The renowned Christopher Sly, who fell asleep as a tinker beneath a hedge and awoke in a palace as lord of brave attendants and delicious banquets, was no less thunderstruck than are today the Bureau of Aero- nautics of the Navy Department and the Air Corps of the Department of War. The satanic apparition of sky power in Europe and President Roose- velt's call for a productive capacity of 50,000 planes a year have translated them overnight from beggars to potential handlers of billions. Both services, after years of cheese-paring, in order to receive. The budgeted pay of 86 flight sur- geons in the Air Corps was cut by the House not long ago from $1.440 to $720 A year. agreed, 392 to 1, to suspend until June 30, 1942, all monetary limitations on the expansion of Army aviation. the House proposed to leave our newest aircraft carrier, the Hornet, without planes, like a battleship without guns. A few weeks passed, and there was voted for the Bureau of Aeronautics a 1940- 41 appropriation three times its largest | grant in any previous year, Earlier Appropriations. For the period between June 30, 1932, and June 30, 1940, Congress allotted $399.853,642 to the Air Corps and $322,- | 554,779 to the Bureau of Aeronautics—a total of $§722408.421. Large expenditures have been required for such projects as the construction of airfields and sta- | war.” tions, and the maintenance, housing and | schooling of pilots and mechanics. In actual combat strength, the net result of this investment of three-quar- ters of a billion dollar that at present the Army and Navy combined possess something like 2,707 fighting planes, of which 1,128 are rated as obsolete or obsolescent. The list includes all pur- suit craft, all armed units, all light and medium bombers, “fiying fortresses” and “flying boats,” all tactical squadrons of Marine Corps and National Guard and the full air comple- ment of all cruisers, battleships and carriers, Nearly three-fifths of the Army’s 520 bombers consist of 300 medium planes of the B-18 type, which were purchased three vears ago at $65,000 each, or $19.- 500.000. Maj. Gen. H. H. Arnold, chief of the Air Corps, startled a Senate Ap- propriations Subcommittee on April 30 by observing that “if you take the B-18 today and send it against modern equip- ment it would be suicide.” Already a decision has been reached to withdraw these 300 bombers from the first line and relegate them to training duty Classified as obsolescent are all the Army’s 168 light bombers and 160 of its 460 pursuit planes. The pride of the Air Corps is fleet of 52 heavy bombers, popular known as ing fortresses.” The flag- Fhip is the XB-15. an experimental craft which cost $250,000 and is described as the world’s most powerful bomber. It was the first military plane ever built with complete living quarters. An all- metal ship with a wing spread of 150 feet, it has four engines of 1,000 horse- power each. An international record was set when it lifted 31.680 pounds—exclud- Ing its own weight of 30 tons and that of its gasoline load—to a height of 6,561 feet. A second distinction was a voy 1o Santiago, Chile, 5000 miles away 28 hours and 53 minutes of flying. Others Cost $185,000 Each. The 51 other heavy bombers are of the B-17 type. costing $185.000 each, or a total of $9.435.000. They are all-metal mono- planes with four 1.000-horsepower mo- tors, a wingspread of 105 feet, a weight of 221, tons and a speed excelling 260 miles an hour. In addition to their own weight and that of gasoline. planes of this type have raised a load of 11,023 pounds to a height of 34,025 feet, carried an equal load 621.4 miles at a rate of 239 reconnaissance its miles & hour and borne their crews, | without cargo. on a 2450-mile non-stop flight from Los Angeles to New York in 9 hours 14 minutes and 30 seconds— &an average of 265 miles an hour. Officers of the Air Corps contend that its “flying fortresses” excel all bombers in the vital elements of speed. miles of radius and lifting power. Nevertheless, pilots and crews ordered to battle in any of these heavy bombers would find themselves at “a distinct disadvantage™ if pitted against the latest developments of war in the air. This was acknowledged in so many words by Gen. Armold, who added by way of em- phasis: “There is no question about that.” The handicap rises from the fact that they are not equipped with three up-to-date features—anti-leak tanks, armored pilot seats and ordnance firing explosive shells. It is a Army and Navy, including the latter's bombing and fighting aircraft and the former’s celebrated pursuit planes, which have made their mark in actual warfare, particularly with regard to maneuvering facility. “We got off on the wrong track,” Gen. Arnold confessed. with a plea that Great Britain and France were equally taken by surprise. The awakening of the Air Corps began some months ago when the DO-17. a German bomber. was shot down in Scotland. To the astonishment of Allied engineers, the tank had kept its | form instead of being smashed, as would have happened with a metal container. Though pierced by 30 bullets, it still held B0 gallons of gasoline. Leak-Proof Tank Mastered. Nazi scientists had mastered a task which the Air Corps undertook several vears ago and then abandoned—the pro- duction of a leak-proof tank. The framework was stamped out of fiber board. The walls consisted of a layer of crude! uncooked rubber between two layers of cured rubber, with an outside sheath of rawhide. When a bullet passed through, the uncooked rubber expanded | and filled the hole. Members of crews were found alive in other German bombers after thev had been riddled with bullets and forced to earth. Tt was learned that the pilot seats were inclosed in light, thin armor of hardest steel. weighing no more than 126 pounds to a plane. There are re- On May 24 the same House\ By | slashing an item from Navy estimates, | | of as many as nine, suddenly find they have only to ask of Congress - ports of German pursuit craft which | continued to operate though subjected to bursts of machine-gun fire. The pilots are thought to have been equipped with helmets, breastplates and leg pieces of steel. The most serious discovery was that on many of their combat planes the | Nazis had supplemented or replaced ma- chine-guns with small-bore, rapid-fire cannon. The latter were aimed like | machine-guns through the noses of pur- suit craft. But in the tails of bombers had been installed turreted wells, each | with two cannon having a 120-degree | cone of fire. | flying in close formation, Gen. Arnold Vessels thus equipped and explained, are able to give mutual sup- port and keep interceptor craft at a re- spectful distance. “That is one reason,” he commented, “why pursuit planes are not getting as many bombers in this 200 One-Pound Shells a Minute. All American military planes are at present armed with .30 and .50 caliber machine guns, in batteries on the largest Each weapon dis- charges 800 bullets a minute. It was proved in several instances that from 3,000 to 10,000 actual hits were needed | to bring down an enemy bomber. One hit from a 37-millimeter cannon has | portance in air battle. lack | shared at present by every plane in both | often sufficed. Fed from an ammunition belt, this gun fires up to 200 1-pound shells a minute. Its range is probably no greater than that of the .50-caliber machine gun. But range is of small im- The most effec- tive attacks, it has been found, are made from distances centering around 250 vards. Though beset with awkward difficul- ties of technique, the addition of armor | and anti-leak tanks offers no insuperable problem. As hurriedly as possible, mili- tary and naval pursuit planes and bomb- ers are being sent back to the shops for equipment with these two devices. But the change of ordnance is a redesign job, so deep-seated and costly that the Air Corps has decided to forego almost en- tirelv any effort to regun its present battle fleet. Information on this point was withheld by the Navy. For the future, however, both sea and land establishments promise that all tactical planes put in service will be pro- | vided with leakless tanks and armor, and that such a proportion of new bomb- | ing and pursuit craft as is deemed neces- sary will be equipped with shell-firing cannon. Suggested Programs Vary. Suggested programs vary between Gen. Arnold’s sober estimate of 20,000 planes ! by the end of 1941 and President Roose- velt's reiterated demand for facilities to produce 50.000 annually. The starting point of either project will of necessity be the current resources of the Govern- ment’s two air-war services. Rigid ac- curacy is not claimed for all the sta- tistics that ensue. When approxima- tions are ventured, they are the closest obtanable under official regulations. On May 24 the Air Corps. in Regular Army and National Guard, possessed some 2.900 “useful” planes. The number on the same date for the Bureau of Aeronautics, including Regular Navy, Marine Corps and Naval Reserve, was 1,813. This gives a total of 4,713 for both | | establishments. The Army’'s combat strength of about 1340 planes was divided somewhat as | follows: 360 observation planes, 460 pur- suit craft and 520 bombers, of which 168 were light, 300 medium and 52 heavy. The Navy's armed aircraft numbered 1.367. which were classified as 320 scout observers, 519 scout bombers, 192 fighters, 144 bombers, or “flying boats.” Testifying a week ago before the Senate Committee | on Naval Affairs, Admiral John H. Towers, chief of the Bureau of Aero- | nautics, said only 192 of the Navy combat planes are less than a year old, and that others range as high as seven | years. Senator Byrd of Virginia, a mem- ber of the committee, calculated that 500 | of the Navy's battle planes have become out-dated for modern combat. No War Reserve of Planes. ‘war. fied Admiral Towers, “to get enough money to accumulate a war reserve of planes.” Of the Navy's armed air force, 679 planes are assigned to sea duty. There are three for each of 15 battle- ships, or 45: an average of four each on 37 light and heavy cruisers, or 148; and about 81 on each of six aircraft carriers, or 486. The Marine Corps has about 100 combat planes. The Air Corps utilizes some 1560 of its planes for transport. cargo and train- ing purposes. For similar functions the Navy employs 108 utility planes, 15 large | and 9 small transports, 230 primary training planes and 58 for advanced | training. | The personnel of the Air Corps. ac- cording to recent tables, is 43238 en- listed men, 2,142 Regular Army officers, 1,001 Reserve officers and 1542 flying | cadets. It listed on May 1 rated pilots to | the number of 1,988, seven non-rated of- | ficers, 30 balloon pilots, five balloon ob- servers, 105 non-rated students and no | parachute troops. The total of Reserve | pilots available was given at 3,300. The latest figures at hand on the Navy's air manpower are those of June 30, 1939, which may not have increased materially to date. At that time the Navy possessed a flving duty personnel (pilots, observers, gunners, etc), numbering 4.633; non-flying officers, 501, and en- | listed men, 17.101. The total was 22325. | The Marine Corps had a flying duty Maj. Gen. H. H. Arnold, U. S. A, chief of the Army Air Corps, whose testimony regarding our plane deficiencies startled mem- bers of Congress. torpedo bombers and 240 patrol | Neither service can at present muster | & single plane by way of reserves against | “Never have we been able,” testi- | —Harris-Ewing Photo. personnel of 491, 15 non-flying officers | and 856 enlisted men. Scattered about the country, under nilitary jurisdiction, are more than 90 flving fields, aviation arsenals and depots and intermediate airdromes. The Army has 15 major air bases in operation. ‘Two, at Denver and Rock Island, guard the entire Middle West. There are two bases at San Francisco and two in the | There are one each at | Canal Zone. Seattle, San Bernardino, San Antonio, Montgomery, Miami, Newport News, New York, Holyoke, Mass, and San Juan, Puerto Rico. About half the country's 2,300 commercial airports, it is said, are convertible to military use. The Navy's major air stations are at Norfolk, San Diego, Seattle, Coco Solo in the Canal Zone and Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The Navy school, at Pensacola. The course is seven months, and those able to graduate are assigned directly to combat units, with commissions at their option as ensigns | in the Naval Reserve or second lieuten- ants in the Marine Corps. There were 617 | aviation cadets at Pensacola on May 1, and pilots are turned out at a rate of 150 a month. Every six weeks the Army graduates 200 pilots, with commissions as second lieutenants in the Air Reserve. Their course of nine months begins with three months of instruction at one of nine civilian flying schools, with a combined capacity of 396 cadets. These are at Santa Maria, San Diego and Glendale, Calif.; East St. Louis and Glen View, | TIl; Tulsa, Okla.; Dallas, Tex.; Tusca- loosa, Ala., and Lincoln, Nebr. The next three months are spent at Randolph Field. San Antonio, and the final three at Kelly Field, San Antonio, known as “the West Point of the Air." Three months of post-graduate work follow at one of the Regular Army air bases. 850 in Training at One Time. In training at one time in the 11 flying | schools are generally about 850 Army | cadets. From the date of matriculation that two or three years are needed to make a first-class combat pilot. A pos- sible reservoir of battle fiyers is indicated by Robert H. Hinckley, chairman of the Civil Aeronautics Authority, who told the National Aviation Forum here last week that the Authority's training pro- gram certified 10,000 civilian pilots dur- ing the past 12 months, at a rate of 30 a day; and can readily increase the number to “several times 10,000 flyers in any year.” They would require one | or two years of added training for com- bat service. The enlisted personnel of aviation must be not only skilled, but specialized tech- nicians. Among those required are radio operators and mechanics, gun riggers, airplane electricians, aircraft welders and metal workers and artisans expert in parachutes, airplane motors and car- buretors, propellers, aviation instruments and air photography. Others are schooled as aviation administrative clerks, ob- servers and code interpreters. Training in such branches in the Navy is part of the regular schedule aboard 5 ship and at air stations. The Army has | found it necessary to set up three schools of its own and make use besides | of seven civilian schools. Scott Field at Belleville, Ill, has recently been con- verted into a basic training school for Air Corps mechanics. Students then proceed to Chanute Field, Rantoul, Il for engine and airplane specialization, or to Lowry Field, Denver, for clerical, bombing and radio instruction. There are 15 courses, ranging from one to six months. 1,000 Graduate Artisans. | The civilian schools are in Chicago | and East St. Louis, IL; Tulsa, Okla.; Glendale, Calif.; Mineola, N. Y.; New- ark, N. J,, and East Boston, Mass. They have produced thus far about 1000 possesses only one flying “in the elementary term, it is calculated | | four-motor, | cause they believe such aircraft ulti- | graduate artisans. Chanute Field han- | About a third of our pursuit ships are obsolescent. dles 1500 student mechanics a year Lowry Field has a capacity of nearly 600 and has graduated 1677 since it opened on July 1, 1939. This hasty sketch of the present con- dition of war aviation in the United | States illustrates the staggering task in- Left: It was the crash—but without fire—of a German DO-17 bomber like this one that gave the Allies their first glimpse of such perfected Nazi developments as the anti-leak gas tank, the armored pilot seat and the explosive shell “cannon” for planes. Right: “Flying fortresses,” pride of our Air Corps. | volved in any program of large and rapid expansion. It must occupy. in the nature of things, two primary fields. First comes the creation of new facilities for the production of materiel. Second is the enlistment and training of new | | fivers and ground crews. Hlustrated is a Curtiss P-36 in action. —Wide World Photo. | Accepting the computation that each plane requires two pilots and 10 men on the ground. tne problem becomes one of recruiting 40.000 to 100.000 pilots and | 200,000 to 500,000 enlisted aviation me- chanics. It means the construction of 120000 to 50000 planes by an industry —Wide World Photos. This twin-motored B-18 Ameri- can bomber is so out of date, ac- cording to Gen. Arnold, that it would be “suicide” to pit it against modern equipment. —A. P. Photo. which is the least unprepared of the country’s munition trades: but which according to high Air Corps officers, has attained even now, nine months after the war began. a potential output of only 500 military planes a month, and can scarcely touch 800 before the end of the year or as many as 1250 earlier than February, 1941. Not Impracticable, They Say. Even a goal of 50,000 planes is not impracticable, according to Ar and Navy air chieftains and spokesmen of the aviation industry. The United States possesses the raw materials, manpower, engineering genius, industrial technique and potential manufacturing plant. The effort would monopolize one-seventh of the national income and a correspond= ing segment of the national energy. These are all factors which remain within the republic's control. The one which it no longer commands— as it did so recently as in 1938—is the element of time. “Two years” were the words which rang like a somber refrain through the many interviews and pages of testimony on which this survey is founded—a minimum of two years to school pilots and ground men in ade- quate numbers; a minimum of two years for building a secure system of air bases; no less than two years for expanding the aviation industry three-fold; at least two vears for machine-tooling the as- sembly lines requisite to mass produc- tion; two years for organizing the pro- curement of materials, and two years or more for training 200,000 new artisans to man the factories. Ba ttléships an Questions Raised by Gen. Mitchell Are Revived B Associated Press Aviation Editor. Defense debate over the long-range bomber—a running argument between some Air Corps officers and some “ground soldiers” of the Army—reminds some old-timers of the famous Billy Mitchell scrap in the Army of 15 years ago. The Air Corps officers—including a few in high office—declare in drawing room conversations that the Army still | is tryving to stifle growth of the air arm, in spite of what they insist has been proved by the German-Norwegian cam- paign and the drive through the Low Countries. The ground arms of the Army, which have a major voice in matters of policy, argue that the infantry still is “queen of battle” and that air power remains | a supplementary force. Oppose “Piecemeal Buying.” The unhappy elements in the Air Corps object to “piecemeal buying” of heavy, long-range bombers, be- mately must be the first line of defense in protecting the American coastlines and, indeed, all waters of the hemi- sphere. Orders have been placed to give the Air Corps 378 such bombers in the next | 18 months to two years. The more out- | spoken of the Air Corps officers say no | less than 1,000 such aircraft should be purchased. ©One Air Corps man in an exceptionally | responsible position has stated to a brother officer that he would attack the Army's aircraft procurement policies publicly if he could obtain no satisfaction | at the War Department. Army policy regarding the Air Corps is a touchy subject—as it has been ever since the fiery Billy Mitchell, as brigadier general after the World War, brewed the storm which brought him court- martial for his outspokenness. Gen. Mitchell, holder of an enviable record in France during the World War and for four years afterward the assist- ant chief of the air force, stalked up and down the land preaching that air power had spelled the doom of sea power in its traditional form. To prove his point he was permitted y Devon Francis, The late “Billy” Mitchell. —Harris-Ewing Photo. with air bombs. and his partisans argue that events in Eurepe have more than proved his con- tentions. Stemming from that, some dissatisfaction with the War De- partment’s procurement policies, is the currenf controversy over the place of the four-motor bomber in our air defense. The Navy, which is not inclined to view any inroads on its sphere of ac- tivity with equanimity, appears tacitly to agree with the Army’s “ground sol- diers.” ‘The long-range bomber of high speed is the outstanding aircraft development of the Air Corps since the World War. There have been other types, but for the most part they have been refine- ments of planes used for similar pur- poses 25 years ago. “Attack” planes (known now as light bombers) are being purchased for the close support of ground troops. in battle. | to sink the obsolete battleship Virginia | Now Gen. Mitchell has assumed the | status of patron saint of the Air Corps, and | d Bombers They serve the same function as the | pursuits, which swept along columns of troops behind the lines in the World War and strafed them with machine guns. Medium-range bombers also are being missions of a few hundred miles—again ir support of ground troops. Pursuits always have led other types of aircraft in numbers. Because of their limited fire power, they are definitely identified with local defense operations. There are other subcategories, such as purpose amphibians and staff planes. Bomber Has Unique Record. The long-range bomber, as it is em- ployed by the Army Air Corps, has a unique record. It is extremely stable in flight, heavily powered and capable of flying as much as 1,000 miles to sea with a bomb load of a ton. It was designed with a “tactical radius of action” to deny any aggressor the opportunity of establishing bases on or near the Western Hemisphere, Air Corps enthusiasts argue that whether a plane can sink a battleship is not important; that if bombers could supporting units—transports, destroyers, cruisers, submarines and aircraft car- riers—the battleships would be left | helpless. The communiques from abroad have told of air bombs sinking or disabling cruisers, destroyers, transports and sub- to question. An overtone to the argument is the old proposal for an air force separated in command from both the Army and the Navy. The Navy has not been em- barrassed by pleas for the separation of its air arm so much as the Army because Navy planes—slower, inore vulnerable ment—are designed for close integration with the fleet's functions. In spite of all the controversy, a new giant Army bomber of 150,000 pounds weight, now under construction near Los | promptly Angeles, may prove to be a straw in the wind on Army air policy. Such a plane, said to have a cruising purchased in some quantity for use on | bomber-destroyers, transports, general- | destroy or cripple the big battlewagons’ | marines, but in what number is open | and in most cases carrying less arma- | | over Germany. | range of 6.000 miles, comes from the school of thought which contends that the way to spike an invasion of the Americas is to attack and destroy it just as it gets under way from a foreign shore, | British Air Rbid Defense Held Well Worked Out By the Associated Press. Britain’s air-raid protection s fairly | well worked out. A fresh analysis of what's what in the air over England is made by Maj. Gen. H. Rowan-Robinson of the British Army in the United States Coast Artillery Journal. He flies right in the face of many an amateur strategist who savs the famous London fog is Albion's great- est protection. Bad weather, says Gen. Rowan-Rob- inson, is all to the advantage of the raiders. They escape observation. They can hide in the fog or clouds and skim | along the tree tops to get the best view of the objective. Over London, the bombers’ problem becomes more complex. The much dis- | cussed “balloon barrage” protects the city. Hundreds of balloons hang in the air, tied to the earth by stout but slender cables. The balloons are kept just under the cloud bank that habitually hangs over London. A raiding plane coming down out of the clouds may hit one of the balloons and be incinerated by the ex- plosion of hydrogen gas. If the raider dives under the balloon, the cables wreck his plane. If he flies just over them, the air artillery knows his exact ele- vation because the gunners know how high the balloons are and how high the clouds are. With elevations known in advance, anti-aircraft artillery is very | dangerous. The general says the anti-aircraft guns worked well—in practice. Moreover, the numbers, quality, range and power of the guns are increasing. Home defense planes, too, got many a “raider.” The most effective weapon against air raids could not get into effect at all. England expects that, the moment a German squadron comes over, her own raiding bombers will wing their way That would compel some of the raiders to get back home to protect the fatherland. Further, the English raiders have an advantage. They don't have to get home. They can land in Prance.