Evening Star Newspaper, February 2, 1930, Page 92

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

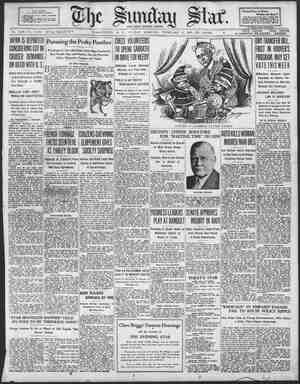

el ; el Tales of the Smithsonian Sun Wizards. { BY JAMES NEVIN MILLER. i DRAMATIC story ic told by William f H. Hoover, distinguished Smith- / sonian scientist, just returned to Washington from one of the most arid regions of primitive Southwest Africa. For three years Mr. Hoover, his wife and young daughter, and Fred A. Greely, fel- low scientist, lived in & corrugated iron hut on top a solitary mountain, 61 miles away from the nearest provision center. Mr. Hoover was in charge of the joint ex- pedition of the Smithsonian Institution and the National Geographic Society to establish a solar radiation observatory at the peak of Mount Brukkaros, a dead volcano. Just before starting back to Washington a short time ago, the Hoovers and Mr. Greely were relieved by Louls O. Sordahl and A. G. Froiland, who ar. rived at the mountain to carry on the work of “shooting” the sun six times a day. More specifically, the purpose of the expedi- tion was to set up a research center which would make reports similar to those being made Yegularly by the Smithsonian solar observa- tories in Chile and at Table Mountain, Calif. The three observatories on three continents are Yeporting daily variations of the heat of the sun that reaches the earth. Every activity on the face of the globe is dependent to some extent on the sun’s radiation, the variation of which is the subject of the recent Hoover study. While individuals are only conscious of such variations in radiation as the earth itself brings about through the procession of the seasons, evidence of the variation in the strength of the sun itself is not far to seek. Smithsonian authorities think there is a definite connec- tion between variation in solar radiation and changes in weather. The observatory in remote Africa may some day warn Chicago of a com- ing drop in temperature. MR. HOOVER describes Mount Brukkaros as: “A small isolated peak rising 2,000 feet above the surrounding plateau, which is nearly flat for a radius of 50 miles around the mountain. The plateau itself is 3,200 feet above sea level. Brukkaros forms a nearly round cup, with the floor of level meadow about half a mile in diameter. A steep rim on every side renders it practically inaccessible except where a break some 30 feet wide drops over a 60-foot precipice to a dry stream bed. The sole approach to the mountain is by -this bed.” Little Betty Hoover was only a year and & half old when her mother and father took her to the remote mountain top. Now she is 4 years old. A flock of chickens and a cow were her only playmates for three years. The nearest human neighbors were Hotten- tots, whose crude bee-hive huts dotted the valley around the mountain. Following some early contacts with these people, Mr. Hoover sent the following information to W ) “The Hottentot tribesmen, black people of Nery primitive habits, actually believed from the start that we Yankees were able to make rain. For months after our arrival on their dusky shores they waited confidently for us to demonstrate our power in this respect. But no rain came, so the black fellows wanted to know what they had done to offend the ‘Bosses,” as they referred to us. One little girl kbven opined that we had closed the skies! “But the natives did not look for rain more frequently than we did. Back in the early days of 1926, until the rain filled our reservoirs, built with the splendid co-operation of Dutch engineers, the only water supply we had was in the crater some 1,000 feet below our resi- dence and observatory. One day, however, we were pretty close to being dried out, so I told 2 native servant to get a couple of our donkeys and fetch up some water. Two days later he returned without the donkeys, claiming he couldn’t find them. Once more I sent him out on his errand. Meantime we'd decided unanimously not to wash the dishes. Next day came along and still we had no water. So we didn't even try to wash our faces. We were a mighty dirty bunch when the water supply finally did come by the third day.” MR. HOOVER gives a graphic description of ! a battle with a ferocious leopard: *“Mr. Greely and I had a precarious foothold on s =mall ledge of the mountain—a leopard had Wdestroyed our chickens, and we were on the hunt for him, had followed his trail almost o the mountain top. Now, however, the tracks were becoming pretty scare, so we had almost given up our search when all at once we saw him, huddled in a crevice hardly an ®arm’s length above us. “Knowing very little about the habits of , we two men were armed only with .22 rifles, poor protection against such ferocious beasts. And we now knew all too well that he was prepared to spring at us at any moment. One miscue and man or beast would g0 plunging into the abyss below. But we couldn’t stop to argue the whys and where- fores of the situation—we had to act and act quickly. " “Seconds passed. They seemed like hours, Wwhen suddenly out & the corner of my eye I saw the leopard assume an offensive position. Somehow I managed to pull the trigger, wounding him somewhere on the back. Yet we weren't out of danger, for the beast crashed heavily almost on our very feet. Fortunately Greely had the presence of mind to fire, and his shot must have hit the mark, for the beast tumbled over the edge, hurtling with tremendous speed to the jagged rocks below.” Despite the extreme isolation, the expedition managed to keep in touch with civilization now and again: The government of Southwest Africa, which helped bulld the corrugated iron house ¢n the rocky mountain top, ran a tele- phone line connecting with Keetmanshoep, the nearest {own, 61 miles awa During the first yeur (1220) a radio, a Ch mas gifi f.om the Battle With Leopard on Narrow Mountain Ledge and Struggle With Giant Cobra Are Among Experiences Described by Government Experts on Solar Radiation Who Have Just Returned to Washington After Three Years Spent on Remote Mountain Peak in Heart of African Hottentot Desert Region. Observatory and instruments used by Mr. Hoover in making his studies. National Geographic Society, brought the adventurers cable news of the United States and the rest of the world via the radio station at Capetown, although, of course, static inter- fered with perfect reception in rainy weather, Mr. Hoover likes to tell about his “home- made refrigerator.” During the second year of the expedition the observatory staff received the modern units of a modern electric re- frigerator, and thereafter ice cream was a regular part of the mountain top diet. The refrigerator also preserved vegetables, fruit and meat, so that the 122-mile journey to the grocery store and back might be made less frequently. A gasoline engine, which was brought up the steep mountainside piecemeal fashion on donkey back, and a generator, sup- plied current for the refrigerator. “A man setting up a solar radiation observ- atory has to be a jack of all trades,” says Mr. Hoover. “Greely and I were carpenters, plumbers, mechanics, electricians, hunters and farmers, alternately.” Discussion of important solar observations usually occupied the mornings from soon after sun-up until 9 or 10 o’clock. The rest of the day was spent in computing the results ob- tained by three instruments, each entirely dif- ferent in workmanship. ‘The computations re- quired six hours or more, The intricacy of the computations may be judged from the fact that once the data for six film exposures of solar radiation intensity have been taken the figures have to be corrected for depth of the atmosphere, omone, water vapor, dust in the air, absorption in the mirror re- flection and absorption in the prisms. At Brukkaros the observers had an average of 240 clear days per year. The observatory, Mr. Hoover believes, may prove especially valuable because its reports accentuate devia- tions in computations reported from the sta- tions at California and Chile. These deviations have put the scientists on the trail of some unknown factor governing the check on the sun’s radiation, THE expedition kept an auto truck in a garage half way up the mountain. Every 10 days some one would drive to Keetmanshoop for sup- plies and mail. On these trips the driver always took a “black boy,” whose job was to walk back in case of accident. The Hottentots have no use for work, but they do not consider walk- ing as labor. Fifty miles in a day they consider a nice jaunt. Hence the emergency “black boys” on the truck. These native boys did their bit and then some on many occasions. Once when Mr. Hoo- ver broke an axle while driving in the sand of a dried-up river, the Hottentot servant trudged 20 miles for help, and offered nary a word of complaint ! Getting water and supplies up the mountain proved to be a great trial. Donkeys afforded the only means of transportation in this regard, two loads of water being brought up dally on the backs of two faithful beasts. “Our very first contact with wild animals,” Mr. Hoover says, “took place back in 1927. One This home of the scientists for three years was a crude place, 61 miles from the nearest provision center. day, when we felt particularly lonely, our isola= tion was relieved by a visit from an uninvited leopard. The visitor paid his respects to our chickens one ‘dark night, and thereafter re= turned frequently. But very soon we learned how to prepare for him, with the result that thereafter he was heard to express his loud dise approval of finding his chicken house locked. “Traps having failed to ensnare him, we ape pealed to some of our friends of the Hottentot tribe for aid in catching the prowler. In due course of time the native captain commissioned a crowd of stalwart boys to go after the oute law. So that in a short time, armed with clubs and abetted by dogs, the youths gave Mr, Leopard a beating that spelled his quick de- mise.” The ringhals cobra, a snake that grows to six feet in length, was a frequent visitor at the Mount Brukkaros Observatory. More than a half dozen were killed near the house. Snake= bite serums were kept necessarily in the ice box at all times, Once a cobra had the impudence to curl himself right on the front porch. Another time, as Mr. Hoover entered the store house, he felt moisture on his cheek and looked up to see & ringhals cobra lying above the door. The snake had spit its poison at him. The scientist ran outside, got his gun and killed the vicious animal. It was mighty lucky, Mr. Hoover explains, that the shot of poison did not catch him in the eye, for then it causes great pain and is dangerous to the sight. CONCERNING the importance of solar ob- servations, Dr. C. G. Abbot, head of the Smithsonian, and himself a world renowned expert on the sun’s heat, says: “The very life of all the plant kingdom de= pends upon sunlight. But why does the Smithe sonian choose.to locate its research centers for studying the sun's heat on remote mountain peaks in desert lands. If we could set up a tube reaching to the outer limit of the atmos- phere and large enough to see through it and the whole disk of the sun, and entirely exhaust the air from the atmosphere, then the measure- ment of the sun’s intensity of radiation would be very simple to calculate. But situated as we are, underneath an ocean of air charged with dust, clouds, water vapor, carbon dioxide, such solar researches in most regions of the earth are very difficult. In order to minimize these difficulties as far as possible, such studies are best conducted in the most dry and cloud- less regions at high-altitude stations.” Dr. Abbot goes on to explain that science is interested in studying the possible connection between solar radiation and the phenomena which the average person knows as the northe ern lights: “It has been long known that the aurora borealis, or northern lights, have been particularly active at times of sun-spot maxie mum, and as these lights are electrical dis- turbances in our atmosphere, it has come to be believed that the sun furnishes not only light rays but also bombards us with electric ions. “Electric ions are known from laboratory exe periments to promote the formation of clouds. Hence, it is quite possible that the electric bombardment. of the earth by the sun, being - more vigorous at times of sun-spot maximum, tends to promote cloudiness; which, in turn, diminishes the amount available to warm the earth, although the direct tendency of increased solar activity is to increase the earth’s supply of radiation.”