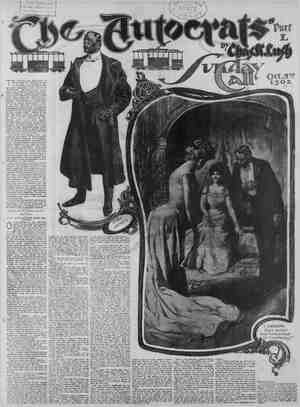

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, October 5, 1902, Page 5

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

e e e THE SUNDAY CALL. the way, and behind were people pressing forward in search of seats. The artist had pressed through, after one frightened glance at the table, but for Hannum there was 1o escupe. & Crosby, aliuw me to present my ;. Mrs. Warrington, ' said Hugh. “Mr. Bld- 1 believe you and Mr. Hannum have * said Bidwell nds with the lawyer. you sit down with us? acant chairs.” are three of us” very red in the face. said Bannerton, coolly. “Lan escaped, and there will be no & him in this crowd. You know John.” With that he pulied out a chair d himself at the table. you must join us,” cried er, this is the first time » seen you since we met on the high , rising and er. There stammered him, and , how sweet was the revenge of Ban- nerton for the “paint-and-powder” insult to the little woman whom he thought the sweetest, the daintiest, and the brightest of God’s creaures! For the “little suip of a girl,” with ready wit and charming grace, became at once the superior being, a he made of this calm, collected man of the men’s world as sorry a spectacle es any yokel picking the fringe of his blouse in helpless awe before the bright eyes of a milkmaid. The two men, Bannerton and Hannum, elipped down the river that night alone together, for Laurie was nowhere to be found. Bannerton handled the oars soft- Iy. with just enough exertion to keep the boat headed down stream. Neither spoke for some time. At last Bannerton broke the sllence. “John,” he said, “you have entered so- clety as an oarsman should—by the water route.” “Not sum * answered Hannum, with an as- of his old bravado. “If they were all lilke Mrs. Warrington I might not object. She is a magnificent woman.” “And the little snip of a girl,” ven- tured Hugh, half maliciously. “Oh, she don’t know so much,” returned the lawyer, savagely. “No,” assented Bannerton, softly. “She not know much. But, John, I would give a good deal for a stenographic re- port of the conversation to-night.” “I was thinking of something else,” eaid Hannum, sharply, and relapsed into silence. The tone made Bannerton withhold further attack, and he darted off into a discourse in which there was a good deal of his friend, Mrs. Warrington, and much more of the plots and plans of Henry Bid- well, whom he had never seen in better epirits. And Hannum was silent, and kept on thinking—thinking of something else. o CHAPTER VIL THE PLOT COMPLETED. The announcement in The Watchman, under flaring headlines, that the Presi- [t was coming to the city, and that Henry Bidwell was the man who had pre- wvalled on the Chief Executive of the na- tion to journey out into the West to make a friendly call, created a sensation. Incidentally, it was admitted that the President would stop at some other ces, but the decided inference conveyed that, without Henry BidWell's inter- est in the matter, coupled with his inti- mac with the President, the Chief Mag- e would have been content to linger It was written in that pecu- , half news and half editorial, seen in American datlies only upon those rare occasions when the chief of a paper rises to what he regards an emer- gency. To Bidwell, who knew the value of advertising, and the strength of the superlative with the masses, no matter how much it might offend or amuse a few, it was an exceedingly satisfactory article. He chuckled as he went over it the second time, and noted here and there the points he had adroitly implanted in thé mind of the guileless Shuttle. The subtle suggestion that there were many things which had better be left to the management of leading citizens and busi- mess men was there just as he wished; seed dropped where it might bear fruit later on. He chuckled again as he thought of the skillful way in which the street rallway matter had been broached at the dinner, and was well satisfied that he had made the proper impression on both Shuttle and Jonathan! Fluttery. The throwing of all these men together on & committee was also a happy inspira- tion; it would result in the breaking down of the personal prejudices that were more or less a bar to his plan of uniting antagonistic forces in support of the or- dinance which he proposed to saddle on the city. While the attitude of Banner- ton displeased him, he gave it little thought; the young man was merely a small candle that could be snuffed out in & twinkling if necessary, But, for the first time in ten years, Henry Bidwell hesitated to advance into & venture which promised to increase his wealth and at the same time to further the interests of the corporation which he served, of which he was a part and which bhad grown to be a part of him. Accus- tomed to lay his plans with absolute dis- regard for what their consummation might cost others, hampered by né more compunction than that of the hunter when he draws a bead on his quarry, much of his success had been due to e spirit of fatalism that inspired him. If men in his way, or in his service, went down to ruin, it was no fault of his; the political graveyard was filled with the skeletons of those who had given their lives for him. He had contrived to make himself believe that the hand of every men wes against the corporation; that the public was but a name for a great, ignorant, hostile muititude, and that ag- gression on his part was merely the only way of securing immunity from attack. The cost of it all, except to himself and to his associates, he had never reckoned. Bidwell had no religion. His moral code ‘was summed up in the single command- ment: Thou shalt not cheat thyself. For years he had ceased to be a man in the sense of having moral responsibilities. He was a living, breathing corporation; a politiclan and a business man—joined llke the Siamese twins. The spirit of hesitation that had come into Bidwell's mind both surprised and annoyed him. He took it as an evidence of waning strength of will, and sought to lsugh it off In his old, careless way. But it was the awakening of a voice within that refused to be silent. Despite 21l his resisting efforts, he was beginning to see some things in a new light, and the light was not a pleasant one. It made some of his past deeds look black to him for the first time, and it cast a shadow on the future. It was the awakening of & consclence, but Bidwell refused to rec- ognize it as such. He knew that his new way of looking st some things, as yet with a shifting, sidelong glance, came frem his talks with Mrs. Warrington. But he sought her companionship more than ever before. She had a way of just touching on the things that were closest to his thoughts as though she read his mind; she made clear the very things he did not want to see. Slowly but surely he was becoming conscious of Right and ‘Wrong in a world of action where he had never before acknowledged their exist- ence, Their talk at the country club on the evening of the “children’s party” had made a deep impression on him, and this conversation had been renewed in a some- what modified form on several subsequent occasions. As though solicitous for his health, she had pointed out the many - _7 ——— et One Dollar and a Half Nov- els for Ten or Fifteen Cents. vexations to which he would subject him- self If he decided to enter political life again, for she had no idea of the daring plan he had concelved of forcing an un- pepular ordinance on the people of the city. As she pictured him now, with re- newed health, in better standing with the public than he had been for years, the people content to let the company en- joy the fruits of the victory gained scme time before in the Federal courts, he had to admit the force of her reason- ing. Perhaps, after all, it was the awak- ening of a conscience, for it was based on a sense of self-interest, and what but self-interest is the mother of a whole brood of consclences? Yes, as Bidwell hesitated, it was but the hesitation of one who has a vagrant idea of turning aside, and is all the waile aware that he will do nothing of the kind; like the drunkard who makes his way to the saloon, telling himself that he will not drink, yet knowing all the while that he shall. The whole effect of the new light was to give Bidwell an uneasiness and mecntal disquietude to which he had heretofore been a stranger. From this he resolved to find relief by plunging into the work of preparnig for the great battle which he had decided should be his last. The prize was rich beyond any he had ever fought for, and the victory would be final, ir that it gave privileges to his company that could not be abrogated for half a century. Already the wires were work- ing in many directions, both underground and overhead. There were some things in his plan of action that were begotten of the im- pression that Mrs. Warrington had made uron the dormant side of his nature. He did not propose to bave any personal knowledge of some of the work necessary to pass the ordinance through the coun- cll. Sprogel had long felt that he was entitled to play a more prominent part than he had been accorded—to get more fun for his money. To gratify this am- bition, Bidwell had decided that the mil- lMonaire was to have full and complete charge of the arrangements for securing the votes of such aldermen as would be likely to be influenced by the only argu- ment that Sprogel was equipped to make. This being left to the man who was in politics for the fun of the thing, Bidwell would be free to devote himself to the work of securing the moral support that was to hold the aldermen in line after they were once ‘“‘got.” With Mayor Thorn he was to deal on one basis, while Spro- gel could negotiate with him on another. Thus fortified ‘against being led into temptation, he prepared to supervise one of the most daring highway robberies concelved ‘since the days of Dick Turpin. The part Bidwell was made to play in connection with the coming visit of the President was alike pleasing to his vanity and helpful to the furtherance of his plans. Congratulations poured in on him from business men and leading citizens, and politicians who had been lukewarm since the blight of his Senatorial ambi- tions made haste to pay homage to this phenix, who seemed destined to rise from the ashes of defeat more resplendent than ever before. The two papers con- trolled by Bidwell were fulsome in their praise, and interwoven with it all was the subtle and oft-repeated suggestion that none was closer in the confidence of the President than the Hon. Henry Bld- well. Even the sharp little Harpoon, the paper that had indeed been a penny- dreadful in the path of this great man, was silent, awed by the fear of being called to account for the slightest criti- cism of the man who was, in the cant of business circles, “‘doing so much for our city.” The Watchman, too, was under the spell, and vied with Bidwell's own or- &an in sounding his praises. Under cover of this paper-made mantle of popularity, Bidwell perfected his plans with address and daring. If Thorn and Moran were much in consultation with him, who could doubt that it was to dis- cuss the details of the President’s re- ception? If they were seen in the hotel gorridor often with Sprogel, and some- times with Lediow in the bank, what could be more natural? Were they not on the reception committee to- gether? There were meetings of the com- mittee, too, &t which Mayor Thorn, Connie Moran, and Tubbett were such well-behaved and conservative gentle- men, imbued with an earnest desire to ad- vance the interests of the city, that Sam- uel Elliotson, who had accepted tha chairmanship after some hesitation, was dispesed to modify somewhat his pre- vious estimate of them. For Shuttle it ‘was something of a triumph, because El- liotson was one of the board of directors of The Watchman, and Shuttle had often contended that Bidwell and others were not as bad as men of Elliotson’s stamp were led to believe. But on one point Elliotson was immovable. He re- fused to place any reliance in any reform- ation of Bidwell so far as his corpora- tion methods were concerned. The sub- ject of street railway legislation had been deftly brought up’at several meetings of the committee, and Bidwell had been so fair spoken as to impress the susceptible Shuttle; but when Sbuttle disclosed his views to Elliotson, he received small com- fort. “I have heard Henry talk before,” said Filiotson, dryly. “It may be new to you, but to me it is an old story. Why, just before they attempted to pass the in- famous ordinance of last spring, Henry talked to me two hours at the club on the wisdom of street rallway corporations being fair and reasonable and making concessions, based on a spirit of equity, to municipalities. When it was up before the Council he had the hardihood to de- fend it to me, claiming that it was noth- ing more than the interests of the cor- poration demanded. It was useless for me to point out that what he called a 1easonable profit was based on a great ex- cess in capitalization—on watered stock. No; on a question involving the corpo- ration, Henry Bidwell is a fanatic. He simply sees with the eyes of a corpora- tion, and can look at the question from no other standpoint.” “I do not quite agree with you, Mr. Elliotson,” sald Shuttle, respectfully. “I believe he has realized the folly of try- ing to fight the public. From self-interest he is now disposed to be fair. I believe that an effort should be made to#rrive at some permanent basis on which the people and the company should continue to do business.” “Mutual interests in these matters are very well in theory, but somewhat differ- ent in practice,” observed Elliotson. “It this was not so we should have fewer courts. There are thousands of people in this city who would not care a picayune if the company were compelled to do business at a loss so long as they rode cheaply. On the other hand, Bidwell looks on the business from the standpoint of a patentee or discoverer. It is no use to argue with him that the increase in traf- fic and the reduced cost of operation should cause a lowering of fares. The en- forcement of such a measure he considers a robbery by which he is mulcted of a proportion of his legitimate earnings. No, Shuttle; when men are making money there can be no such thing in their eyes as a reasonable reduction in their profit. Any increase is reasonable; for with that in view they embarked in the enterprise. But a decrease is unreasonable, especial- ly it enforced by a force other than rival capital, which is known as compe- tition.” “I think Mr. Bidwell is inclined to be fair,” insisted the man of the inky cloister. *“‘He has talked with me a good deal of late about the advisabllity of ending this strife.” “He has, has he?” exclaimed Elliotson, darting a keen glance at Shuttle. “In that case, I would advise you to take out an accident policy. When Bidwell talks the fairest he is the most dangerous. De- pend upon it, when he enters into any ne- gotiation with the city it will be with the end of retaining what the company now possesses, or of getting more. To do otherwise, he would be untrue to himself and his corporation, which is the same thing. But, after his recent experiences with the temper of the people of this city, I do not think there is much likeli- hood of his making another move for some tinle. They are lucky to be let alone.” Shuttle said nothing further to continue the discussion, but he was far from be- ing convinced. he had found hfm so ready to agree to the arguments advanced in favor of mutual concessions that he felt certain that he had made a deep impression on the street railway man. Besides, Shuttle had & new- born ambition. He felt that he was the man to really ‘“do something for our city” by bringing Bidwell to see the de- sirability would be to the advantage of both the consumer and the producer—a wiil-o'-the- wisp chased by many men with more gray matter than Shuttle. But the fuli getivity of Bidwell was lit- tle understood even by those who thought they knew him best. It was well enough for Klliotson to talk in a general way, but of the details of Bidwell's plans and plots and of the full secret of his power he -really knew but little. - Bannerton came nearer having an adequate conception of the wide scope of Bildwell's Influence, coupled also with some realization of the details of his methods. While Shuttle and Elliotson were talking, Bidwell was in consultation with Sprogel and Ledlow. It was an important conference and was fraught with some peril for Bidwell. Led- low had, at the last moment, shown symptoms of ‘wavering, and it was Bid- well’s task to Inspire him with new cour- age. Of Sprogel, he had no doubt, as he was sure to abide by whatever he (Bld- well) might decree in this sort of an ad- venture; for to him it was more of an adventure than a ventyre. But Ledlow knew the blind subserviency of the mil- lionaire to Bidweil, and consequently any- thing he might say would have little weight with the banker. The three men met in the office of Bid- well, as it was there that he was prepared to submit something in the way of docu- mentary evidence in support of his plans. “‘Come,” said Sprogel, in his deep, rum- bling voice, “let's get down to business. Spread out your lay-out, Henry, and let us see what you have framed up.” . “I have simply proceeded aléng the lines originally marked out,” sald Bidwell, “and I think I am safe in saying that everything is working smoothly. We are sure of a majority of the Aldermen when the time comes; we have the Mayor where he can never go back on us; and, when it comes to the pinch, we shall have the best element of the city with us. I can see nothing in the way of success.” _ ““We had the Aldermen before,” sald Ledlaw, doubtfully, “and we also had the Mayor. But when it came to the test, gentlemen, they fell away from us. I tell you the public clamor is a great force, no matter how lightly we may pretend to hold it ourselves, The public and the press are factors that we have to con- tend with in matters!of this kind.” “The Aldermen would have stuck the other time,” answered Bidwell, “‘and this time we have the Mayor where he cannot flinch under fire. Just glance over this letter.” As he spoke he picked up a letter that was on the desk before him and passed it over to Ledlow. The banker read it over, smiled, and as he handed it back he sald: “I guess there is not much doubt about him. How did he ever come to write such a letter?” “A vain, weak man can be led into do- ing anything you wish,” replied Bidwell, with a knowing smile. “It is only neces- sary that you know his weak spot.” “Well,” observed the banker, ‘all the men who will oppose this ordinance are neither weak nor vain.” “But_they can all be reached,” put in Bidwell. “I tell you, Ledlow, I never felt more confident in my life. I will stake my reputation against a penny that this will go through this time.” “That is an even bet,”” rumbled Spro- gel, with a guttural chuckle. “It is well enough for the Aldermen and the Mayor,” continued Ledlow, pay- ing no heed to the interruption from the fat millionaire. ‘“But it is a different mat- ter when you come to deal with the press and the public.” “Ledlow,” said Bidwell, rising from his chair and pacing back and forth, “I will g0 more into details than I thought would be necessary. The public, the great, solid business Interests of the city, I am sure of. The plans that I have formed will bring them into line through agencies that T cannot explain even if I tried. This much I will say: there is hardly a man that amounts te a row of pins in this community on whom I have not got some line. Of the press I am sure now, with the exception of The Watchman. But it will be the surest of them all if my plans are carried out.” “And how do you Intend to get The ‘Watchman?’ demanded Ledlow, incred- ulously. “I intend to buy it,”” answered Bidwell, impressively. ] “So you have got to Shuttle at last, have you?' exclaimed Ledlow, with a look of surprise and admiration. » “No, he could not stay bought if he sold himself,” returned Bldwell, with® a- sneer. *“I have done better than that. I can buy the paper. It is a good invest- ment in itself, for it is paying dividends.” “BuY the stock in The Watchman!" ex- claimed the banker. “Why, you could not get it for love or money."” “Mix in a little revenge and there is a different result,”” said Bidwell. ‘“Look at this scrap of paper.” Ledlow started back in surprise as he glanced at the paper laid before him. “Why,” he exclaimed, “it is an option L In his talks with Bidwell, * of making . concessions that. . in official life. on the stock held by Martin Yarr. He has sold out Elliotson and his compan- fons. How did you get it, Henry?” “It is a long story,” answered the ma- nipulator, with a smile of satisfaction. “A light remark made by Elliotson in the club was the foundation on which I built. A chance to make a handsome profit and to get even for a fancied insult was more than Yarr could resist. What do you think of it now?"” (UL 'will take that stock myself,” ex- claimed the lean banker, his eyes glowing. “No," said Bidwell, firmly, “‘we will divide it evenly between us three.”” “T ought to have a newspaper,” put in Sprogel. *“If I had a newspaper I could make it a contest between a paper and a hotel to see which is the most expensive luxury for a man to own.” : Bidwell plunged in, and fn detail went over the scope of the plan that“he had mapped out. Ledlow was an attentive listener, byt Sprogel yawned at times—it required too much thinking to follow Bidwell, and he was content to trail along with blind faith in his Mentor. “Well, well,”” exclaimed Ledlow, atlast. “] cannot see but you have things ar- ranged in a masterly way, Henry. There is nothing to do but to go ahead. The first thing is to buy Cosmopolitan Street Raflway stock. I see that it is at eight now, as it has been for the last. six months.” “Yes,” sald Bidwell, “and the work must begin to-morrow. This stock is not only for us, but it is also for others.” “\ghat do you mean?" demanded Led- low, sharply. - “I mean that it will furnish the sinews of war. There can be no harm in allow- ing a few of our friends in the council to take a flyer in.stocks. Later we will let in a few leading business men on the outside. We get it at eight. As soon as this ordinance is introduced in the council it will jump to twelve. That gives us a margin out of which we can take new stock in the name of our good friends There is no law to pre- vent an alderman, nor even a Mayor, from speculating.” ’ “Henry,” exclaimed Ledlow, dropping back In his chair, and gazing on Bidwell with undisguised admiration, “you are’a Napoleon—a civic Napoleon.” Bidwell chuckled, and slapped his hands together, as he did when he was pleased. “T am just beginning, Ledlow,” he said. “I have been working long enough for others and the party. It is time 1 looked out for myself.” “And I think I hawve done nothing but make money while you have been throw- ing yours away,” oserved Sprogel. “You have lost a lot of money in the last ten vears, Henry—money that you couldn’t get hold of.” “You will more than get even deal, Sprogel,” retorted Bidwell, nettled. 4 “Oh, that is all right, Henry. mind me,” sald the heavy-eyed man, good-naturedly. “There is one point I forgot,” said the banker. “I forgot to speak about the courts. Are they not llable to overturn everything in the end?” “Ledlow,” said Bidwell, impressively, the courts are with those who have the heaviest artillery—the big guns of tho law. Have we ever lost anything in the courts?” “Not yet,” sald Sprogel. CHAPTER VIIL BANNERTON CONFIDES A SECRET. To his friend Mrs. Warrington, who was ever ready to listen to what concerned his welfare or threatened his peace of on this a trifle Don’t money- mind, Bannerton came with what he had" learned of Bidwell’s plans, and to talk of some things which had arisen to perplex ' him.- To some extent, the young man had come to the part- ing of the ways—one of those crises that come -to men when they feel that they can no longer follow the beaten path, but-must turn aside, and cut a path thrcugh. the ' wilderness. . To follow the dull routine of his present life appalled him, for he saw nothing before him but the flat plain, rising nowhere, and de- scending in the distance. He had no mind to grow into the life of a petty office- holder, subject to the whims of some drunken politician or. the cold calculations of a sober one. The realization brought with it a sense of shame, for ha saw how unbecoming had been his jibes at other men while he was doing naught himself. Besides, and it has much to do with the unrest that was in him, he was burning with a fever, of which, for the first time, he was now fully aware. He was in love with Edith. Like the bursting of the dawn in the tropics it had come upon him suddenly, all in the dazzling light of hope, only to leave him prostrate and in de- spair when he came to look upon it steadily. What had drawn the curtain aside? What had transformed the companion of his idle hours, his comrade in the woods and flelds, his light-hearted friend of everyday life, into a divinity before which hg now kneit in worship, eager in desire, yet awed by his own presumption? A look. The 'look of another man, one glance from his friend, from John Han- num, as they drifted down the river to- gether in the moonlight., “I wondered if you would come to- night,”* said Mrs. Warrington, as Hugh held her hand a moment and looked into her face. ‘““We can spend the evening to- gether without fear of interruption, for Edith will not be here.” Instantly, and for the first time, a strange thrill ran through the young man. It was his first jealousy. ‘““Where has she gone?” he asked, try- ing to appear unconcerned. “To some re- ception?” ““Oh, no,” responded Mrs. Warrington, 5 e e ——— “she is visiting' Anne Dyles, and will spend the night there. But where have you been for several days? I have been eager to see you." “I have been alone with myselt,” an- swered Hugh, seriously, at the same time dropping into a chair, “Yes,” he added, In answer to a look from Mrs. Warring- ton, “I have been alone with myself, Aunt Warrington, for the first time in many years." ““Well, well,” exclaimed Mrs. Warring- ton, arching her eyebrows. ‘You are the last person in the world I should have suspected of doing such a thing, Hugh. And did you find out something about yourself? Most persons do when they take themselves aside.” “‘A great deal,” replied the young man. ““Enough to convince me that I have been 2 fool in a great many ways.” “In love or politics?” queried the widow, carelessly. “In both,” cried the yéung Hotspur, springing to his feet, and. walking back and forth, while his companion settled herself, back In her chair and watched him with an amused expression on her face. “In both leve and politics, if by politics you refer to my means of liveli- hood at present. What have I done dur- ing the past three years?’ he demanded, confronting his friend by pausing a ment in front of her. A ' “Nothing very bad, I hope, Hugh,” she answered. ‘‘Most men of sense pause at times in the course of their lives, and go through what has been your experis ence in the last few days. It is not so bad when vou are yet young, but when 2 man looks back on an entire life wasted it is a different thing. Good will come out of it all, Hugh."” “What bhave I done but make a fool of myself?” continued the young man, resuming his walk back and forth, and {Znérlng her words. “I have grown to an idler of the most despicable sort, drawing wages for doing nothing, and doing nothing with the money that came to me, in spite of the fact that I did not earn it. And what can be my future in such a place? To become accustomed to a life that I could not maintain if I were cast out at the caprice of a man like Henry Bidwell, to become a seedy hanger-on, waiting for crumbs that never fall. And yet, if this were all, it would not be so bad.” He flung himself on a chair and burfed his face in his hands. “My dear boy,” sald the woman, “you have had no trouble. Your life is be- fore you, and not behind you. Do not jmake me believe that you are a coward, Hugh.” “I.am not,” he cried, springing up again and looking her In the face. “Whatever else I may be, Aunt Kate, I am not a coward.” * She thought him very brave and hand- some as he stood there, his slight figure erect and rigid, and his eyes flashing, and she was proud of him, as a mother might be proud of her son. “Oh, my best friend, my only friend,” he cried, selzing her hands and covering them with kisses, “I must tell you the crowning act of my folly. I have fallen in love with Edith.” “My poor boy,” she said softly, disen- gaging her hands and pushing him gently from her, “have you just discovered that?"” “You—you knew {t?’ he stammered. “Why, I did not know it myself.” “Of course not,” she answered, with a laugh, “but I did. Now, if you will take a seat and behave yourself, I will talk to you. But if you keep this up, T must laugh at you, Hugh, for love is a disease that we all laugh at until we have it our- selves.” - “I know I have made a fool of myself,” began Hugh, humbly, “but- oy “Not at all, Hugh,” said Mrs. Warring- ton, kindly, ‘““for something higher than ourselves guides us in such matters. But the time has come when you must mark out your course in life and follow it. You have formed a feeling of strong an- tipathy to Henry Bidwell, which is unfor- tunate under the circumstances. He could be very useful to you, and might advance your interest in lines outside of political life.” “His business life is worse than his - political life,” said Hugh. no further aid from him.” “Well spoken,” said Mrs. Warrington, a little flush coming to her face, “and I share your feelings. A strange fascina- tion has attracted me to him, Hugh, and vet I have always felt a repellent force. It has been a mingling of feelings that I have never been able to analyze. I be- lieve that I have exerted a similar influ- ence over him, from which he has tried to free himself in vain. The first time I looked into his eyes they seemed to say something to me that I knew, but could not reach. He has told me many things about himself; not all, but many things. Back of it is something else. He will tell me some day. It is something that I know, and yet do not. Like =z name that has slipped one’s memory, it is almost clear to me at times, as a boat coming ashore out of the mist. Then it has faded and gone. But some time I shall know.” . She stopped, looking out into space as It in a trance, and Hugh stood amazed. He reached out his hand as if to support her, at which she turned and, with a laugh, said: o “How foollsh that must have sounded to you!” - “No,” said the young man, seriously. “I understand. I understand. But I, tvo, cannot explain. I tell myself it is the methods, and not the man that I dislike, but sometimes I feel as if that were only half true.” A “But we do object to his methods, Hugh,” said Mrs. Warrington, “as must every honest man and woman. He tells 5 “I will acept The Remarkable Heroine of o ““Alice of Old Vincennes> N a recent analysis of what it is that makes the romantic novel so fasci- nating it was shown that it is not merely a combination of swash- buckling heroes and blood-curdling adventures, but the development of char- acter, of living, pulsating emotions, of hopes and fears and love and hatred, such as we ourselves know it to-day. All this was apropos of the remarkabls success of ‘‘Alice of Old Vincennes, whom Maurice Thompson has made a roine unique even in romantic literature. Note what a heroine she was, for it is now known that she is taken from real life in the dark days of the Revolution: “And yet we are looking back over but a little more than a hundred and twenty years to see Alice Roussillon standing be- neath a cherry tree and holding high a tempting cluster of fruit, while a short, humpbacked youth looks up with longing eyes and valnly reaches for it. The tab- leau is not merely rustic. It is primitive. “Jump!” the girl is saying in French. “Jump, Jean! Jump high!" “Yes, that was very long ago, in the days when women lightly braved what the strongest man would shrink from now. “Alice Roussillon was tall, lithe, strong- 1y knit, with an almost perfect re, judging by what the master sculptors carved for the form of Venus, and her face was comely and winning, if not ab- solutely beautiful. But the time and the place were vigorously indicated by her dress, which was of coarse stuff and sim- ply designed. Plainly she was a child of the American wilderness, a daughter of 0ld Vincennes, on the Wabash, In the time that tried men's souls? ““The sturdy little hunchback did leap with surprising activity, b:t the treacher- ous brown hand went higher and higher, so0 high that the combined altitude of his jump and the reach of his unnaturally long arms was overcome. Again and again he sprang vainly into the air, com- lfcl.lly, lke a long legged, squat bodied TOg. ‘“‘And you brag of your agility and strength, Jean,’ she laughingly remarked, ‘but you can't take these cherries when they are offered to you. What a clumsy bungjer you are.’ “‘l can climb and get some,’ he said, with a hideous grin, and immediately em- braced the bole of the tree, up which he began scrambling as fast as a squirrel. ““When he had mounted high enough to be extending a hand foy a hold on a limb Alice grasped his I near the foot and pulled him down, despite his cling- ing and struggling, until. his hands clawed the soft earth at the tree's root, while she held his captive leg almost ver= tically erect. “It was a show of great strength, but Alice looked quide wunconscious of it, laughing merrily, the dimples deepening in her plump cheeks, her forearm, now bared to the elbow, gleaming white and shapely, while its muscles rippled on ac- count of the jerking and kicking of the luckless Jean."” It is such a heroine and her develop- iment in a woman who can suffer and love and love and suffer until her final triumph that has made all the rare charm of “Alice of Old Vincennes"; a ‘woman, indeed, whose strength and skill ' were such that her lover had to prove his mastery with his good sword arm be- fore she found that she really loved him. And then—*deep down in her heart she was pleased to have him master her so superbly, but as the days went by she never sald so, never gave over trying to make feel the touch of her foll. She did not know that her eyes were getting | through his guard, that her dimples were lthblal“» M:hh.mmln its middle.” A 80 e goes through the beautiful psychological study of the bud- ding and birth of a woman's love. At §1 50 the book has had a tremen- dous sale both in the East and in Europe. It was dramatized shortly after its first appearance for Virginia Harned snd made a fortune for that talented actress. The play has never been seen out here—the book itself will create a furor. And so lé has aom:l about mrouteh the Sunday ‘all's new literary policy t may have both the mymmm,:“mu cents. The play is shown in some magnificent full-page {llustrations of scenes from Virginia Harned’s plece—the book will be published In full in three issues, the first installment of which wili be pub- lished Sunday, October 19. The next two will follow on October 2 and Novem- ber 2. It 1s an offer that has never been equaled in Western journalism. The scenes from the play, which are truly ‘masterpleces of photography, are worth R R © e e u s is o the . After *‘Alice of Old Vincennes” comes ‘The Leopard’s Spots,” “The Gentleman From Indlana,” “When XKnighthood Was in 0 “The Gospel of Judas Iscariot,” etc., etc., which latter will create a sen- sation without a doubt. But just think it over. 15 cents. Can you beat it? me he 15 not to have anything to do with the attempt to push the ordinance through the council. He is merely to pre- sent the ordinance in behalf of the com- cried Hugh, *“does he lie, even to you? He is in it, body, soul, and raoney. He is the arch-conspirator.” ““Come, Hugh," she said, quietly, it down together and have a et long The young man came away from Mrs. ‘Warrington that night knowing much more of himself, and of others, than he had ever realized before. For the first time he had a coneeption of the greaf and unselfisk affection she had for him, and he marveled at it. They had talked of many things—of his early life; of the love she bore his mother, her girlhood friend: and of the creed that she (Mrs. Warrington) pro- fessed, which was so much like his own— which have made them s6 much in com- mon. But of Edith and himself she had little to say, avoiding his leads In that direction, and giving him plainly to un- cerstand, without saying it In so many words, that it was a matter in which she cared to take no part. ¥ “My dear boy,” she sald at last, driven to some expression By his persistence, ‘‘there are some things a man and a Wo- man must settle between themselves. There have been more love-knots snarled by outside fingers than were ever neatly tied by them.” On the other hand, she showed a deep interest in the plans of Bidwell and her thorough knowledge ‘'of all that was in- volved in thé impending struggle showed the young man that she had given the matter mach study and that she had a full comprehension of the great power this strange Man wielded. And yet Hugh noted that not once did she seek to dis- suade him from combating a force which she all but admitted was an overpowering one. Perhaps, by reason of his thoughts of Edith, his head was not as clear as it night have been. -At any rate, it was not long until much that Mrs. Warrington told him that evening came back to fim with its full meaning. Perhaps it was the force of after events that unveiled his cyes and gave significance to much she said; and certain it is, she did not choose that he should now understand it all. ‘The problems that confronted Banner- ton kept him awake far into the night. Looking back, he saw the mistakes that haé all been so easy, while before him were the right things to do, that as seemed so hard. It was the full knowl- edge of his love for Edith that most op- pressed and awed him. He looked back as their companionship, which had been socmething more than that of brother and sister, and something less than that of lovers. Where was he to begin, and how was he to alter the relations that had thus grown up between them? That she was to become the wife of another man, that he was not to have her always for his own, had never oecurred to him in all the years of their acquaintance. Perhaps she would be grieved and surprised when he told her of his true feelings—the new ones that now burned in him with all the passionate desire of his ardent and tmpulsive nature. Perhaps she would only laugh -at him. He groaned at the sug- gestion. Then his thoughts took a new turn. Suppose she flew to his arms and accepted him? What had he to offer? he, witk a precarious position, paying hardly enough for them to live on' comfortably in a modest way; one which he was about to jeopardize by the stand that he in- tended to take in opposition to the plans 0? her uncle. Why not go over, body 2nd soul, to the service of Bidwell, whis- pered the tempter, ingratiate himself in the service of the frée-booters, and thus win the approval that would be of serv- fce to him in his suit? The next instant he sprang from his bed, and fell to pacing beck and forth in his room, his hands clenched, and his jaw set. It was over in an instant, and, throwing himself down again, he buried his face in the pillow. / CHAPTER IX. UNDER THE ROSE. . The surface of life in the city was as yet unchanged by the work of Bidwell and his assoclates. It moved along in its accustomed channels, turgidly or im- petuously, among the different classes that form a large community. For a city is made up of circles, or groups, great and small, divisions and sub-di- visions, the members of which have ap- parently little in common, whose mode of life is dissimilar, and who really kaow as little of each other as do Hottentots and Esquimaux. The business men, calm in their satisfaction with the present, pursued the even tenor of their lives, content to manage their own affairs, and leave the greater affairs of public in- terests to men whom they dimly classi- fled ag politicians, and who, they fondly imagined, stood In much awe of them. They scanned the headlines in the daily papers, were interested in the war in South Africa, from a strictly commercial standpoint, and looked upon the killing of natives in the Philippines as a mere incident in the furtherance of a business policy, as to the wisdom of which they were divided. As a class they were as if endowed with two eyes focused for different distances. With one they saw only that which was close to them— their own immediate ventures; with the other they looked far away, and saw only that which remotely affected them. With neither could they see their inter- ests midway between the extremes. Hen- ry Bidwell was now hard at work pre- paring to take advantage of this biind- ness, to the great profit of himself and his companions. The great mass of the people, clerks, artisans, laborers, small shop keepers, workingmen, and working- women, were, as they always are, of varying sentiment and opinion, in cordance with their lot. To this great mass, in bulk nine-tenths of the whols population, Henry Bidwell gave no thought. But there was one circle that was buz- zing and humming, and all agog with the new life that had ::‘fl:u n.mn ‘was the political circle, new life came mw g which Bidwell had pro- vided, and which Herman Sprogel, the fat millionaire, had distrfbuted with a discreet hand. Ready money was the motor that made the wheels go round, and produced much life gayety. ‘What class {s so mu., mflmto:lfi as the politiclans of a city political and official circle is a guild with a code as strict as that of the Masons, and you do not get In ulu:. you ‘-’.r. eligible !o; membership, and have, & season o dissipation, and disregard for certain rules that govern most men, made your- self one of the elect. After that, you ‘are in a position to see and to understand, and not before. And the chances are many to one that in performing the in- itiatory rites you will not care to te’ about your comrades. And thus it is th- those who write most freely and mos entertainingly about these matters ar estimable young women—fair authoress- es, whose very sex is an absolute guar- antee that they were not participants in the scenes they deplct. The saloon down- town, the all-night restaurant, and the settings which form the background to the muni drama, wherein move men who make city laws, spurred on to & glddy pace by wine and women. It was In this circle that Connie Moran now set the pace to faster time than had" been known for many a day—wine, and midnight suppers, and revelry until morn- ing: Connie paying for it all, and no one asking any questions, A grade above this, in the La Jole Club, Mayor Thorn ruled with majestic grace, attended by Tubbett, resplendent in silk hat and frock coat—exact duplicates of $1 50 books for | the Mayor's—holding court until the sea- sonable hour of midnight, when he was Virg'mia Harned's Great Play and Maurice T:hqntipson’s Famous Book, All inOn s Al P accompanied to his home, a few blocks distant, by Tubbett, and sometimes Con- rie Moran, the shrewd little president of the Council. An hour later the pair— Moran and Tubbett—would appear in Ben Locksiey’s place, and there stand by the hour, drinking champagne over the bam as if it were so much beer, and paying for it as if they were the possessors of mil~ lions made by a deceased sire. The signs of impending activity along legislative lines had been noted by Ban- nerton, with quick insight into their true meaning, and he feit certain that tha time was not far distant when these tools of a greater mind would begin their work in the service of their master. His stand- ing in this circle was as yet such that he was always welcome, and there was little concealed from him. But he knew that as soon as he should appear as an 0ppo- nent of the ordinance which he felt sure was being drafted, he would no longer be “hail fellow, well met” with the co- terle. With the idea of keeping in touch as long as possible, he had spent many of his nights among these men, and he looked now with loathing on the life in which he had moved. Again he felt like dropping the whole matter, crawling into his shell and bowing to the will of Bid- well and his assoclates. But the old spirit came back to him when he thought of some of the things Mrs. Warrington had so plainly said. and he was staunch In his Jetermination, His vernal and pure love for Edith, however, made him resolve that he would no longer mingle with these men. It seemed to him as if it were sacrilege to do so with the theught of one so pure in his mind: And yet— and yet—oh, what a tangled mesh it all was, and no wonder that he knew not which way to turn, between love, self- interest, and what seemed to him to be his duty. It was now close to the time when Bld- well would be ready to begin the battle. He had worked incessantly, and with all his old cunning. So cleverly had man- ipulated that each of his confederates felt a glow of pride, and deemed himseif an indispensable agent In carrying for- ward the campaign. Ledlow had secured large holdings of the coveted stock of the company with a skill and secrecy that did much credit to his sagacity. Sprogel, with the fearlessness of one who had never known defeat, and whose moral code justified him in buying anything he might covet, had deait with the Mayor and the Aldermen as if he were dealing with so many contractors. When he con- sulted his memoranda and glanced at the figures at which he had secured the votes of some of the Aldermen he was over- whelmed with his own shrewdness and business acumen; but for the Mayor, the president of the Council, and for several of Moran's most intimate assoclates in the Councll, he had conceived a deep hat- ~red. “The damn scoundrels,” he growled to himself, “they have sandbagged me!™ But these feelings he had carefully con- cealed from them, and was as genial a man as ever bought men or drinks. May- or Thorn, swelled up to great proportions in his own eyes, by turns feit himself the master of the situation, wondered at his moderation, and dreamed of the favors to come from those whom had placed under such great obligations. So it was, down to the cheapest Alderman, who deemed a few hundred dollars a gift that the gods had thrusg upon him. For each of these men had.. unknown to Sprogel or Ledlow, been ai least once in consultation with Bidwell, and had been under the spell of his soft and persuasive tongue; and all had come away with a sense of obligation from the simple advice, delivered with a signif- icant glance, that they “See Sprogel.” With matters standing thus, Ledlow, Sprogel and Bidwell met in the private office of the banker. “Well, Henry, I guess we have got the thing coopered up all right,” sald Spro- gel, as he dropped into a chair. “The only thing to do now Is to introduce the ordinance and then smash it through.” Bidwell pursed his lips, and made no reply. ““There should be as little delay as pos- eible,” ventured Ledlow. ‘“We are car- .. rying a big load.” ‘How many men have we solid, Spro- gel?”" asked Bidwell, quietly. Direct?” queried Sprogel. “Direct,” repeated Bidwell. “I have ten under contract,” sald Spro- gel. “But,” he added, “they deliver the votes of twelve others, or they receive practically nothing.” “Precisely,” said Bidwell. “You have just ten votes sure—less than one-third of the Council. You have all you can get, Herman—all you can get your way." “My way!” exclaimed Sprogel, a purple fiush coming to his heavy face, “I do not know that it is my way any more than It is yours, Henry.” “True,” replied Bidwell, softly. “T will . amend by saying that way, instead of your ‘way. But the fact remains that we have all we can rely on to stick to a fin= ish, no matter what may happen.” “Do you mean to say that after all thiy. ‘work we have only one-third of the Coun. cil on our side? put in the banker, his face ashy gray. “In certain contingencies, yes,” an- swered Bidwell. “These men alone will stand and face the storm that may break on them.” “Then,” sald Ledlow, ke a groan, And he groaned again. F “By God!" roared Sprogel, starting his feet. “I will go through with v.nz now, no matter what you do, Henry Bid- well. Ledlow,” he eried, facing about and extending his hand to the banker, “I ‘will stick. We will push this through to= gether."” The banker made no reply to this gal- lant outburst, but sat with his chin fall~ en and his eyes set on Bidwell iIn a glassy stare. For a moment Bidwell gazed In admir- ation at the huge, quivering form of Sprogel. He felt a thrill of seifish in baving such a friend. The ‘with his passion spent, and of a sudden, his chair. A with “we have lost.” H if i!ig i i ¥ 3 H R o | i et 5755 fnt g [ i Ledlow, thirteen votes to your ten comes,” he concluded, f it | i H Skt