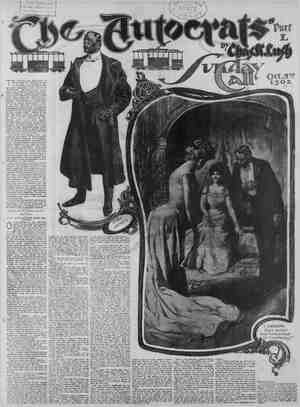

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, October 5, 1902, Page 4

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

‘THE &U NDAY CALL. B T P ST HANC W 0 S IR B U P Nt S PRSIl DI RSV SIS A, 10 W bl vl diorl e = et SR NSO P A S Pk € 0 s R AR A O A L L s S s e L DA S P IS e R e R RRPOU I, L DS ed duties of man- rs. Pompous, bis readiness to thrust body, he was yet a factor ng the events of the city. RBager monplace distinctions of civic aces which men of ud more ability were com- e, and which gave him a less leisure pelied to de standing in the community and an im- portance in the eyes of the public greauy in excess of his deserts. Ledlow, silent and calculating, but with the outward polish and manners of a gen- tleman, was the type of men who rule by the judiclous dropping of a hint that a note is about to fall due, or that there is & ney st ency impending that may reduce a line of credit. Hermen Sprogel, the millionaire! Here was a character about which Bannerton kad often wondered, a type indigenous to the American republic. At middle age, shattered in health by youthful follies, millions had been thrust upon him. Ger- man by name, but with a Celtic instinct, he turned to politics as the sphere in which he might find diversion and at the me make a name for himself. Soon ed in a game of which he did not the rudiments, and for which he kr was not mentally endowed, he fell back on the use of his money as a weapon with 24 which he might punish his opponents and make conquests with which to reward Lis followers. Bidwell early saw the ad- sentages of an alliance with such”a man, end ingratiating himself, first as a friend- Iy tu he finally became his mentor, end taught him all that was vicious both in business and in politics. Perhaps if this man had been thrown with better sdvisers he might have grown to be a factor for good; but as it was he became & great power for evil, made of honest men panders, seduced the young and was ectuated by no higher ambition than to be “in politics for the fun of the thing"; it was his delight to hear himself called & “good fellow.” Ah, thought Bannerton, if he had only read one good book when he was young! The newspaper representatives came next; Shutt! now editor-in-chief and managing editor of The Watchman, and Jon 1 Fluttery, chief editorial writer &nd shaper of The Spinning Wheel's des- tiny. As Bannerton looked at the pair engaged in conversation, he saw two men made great by sheer prehensile ability; both had risen by clinging on. And as he looked, there came to him a vision of the two men who had founded and made great the papers these men now conduct- ed; who had prevented the development of men like Henry Bidwell; who were wise in their generation, and knew men es well as books. Coming to The Watch- man twenty years ago, Shuttle had been essigned to work at a desk in the tele- ph room. Death and the blight of g Alcohol had cleared place after e for him, and steadily he had mount- i, untfl at last he stood at the head of the leading paper of the city. And yet, not once in all this time had he been out of his cell, nor varied the routine of the prison life that bound him to his task. Within these narrow confines he had learned 2!l that he knew of the great out- side world—from other papers, from the talk of men in the same business, and recently from men who came to him wearing masks, or on dress parade, to achieve a purpose through him. Pin- ned down by an accumulation of duties, for he still thought himself e drudging copyreader of twenty years , he had taken no time to learn, to broaden, or to reach out and grasp the full import of ever-changing conditions. To add further to his perplexities, he stood now between two rival factions of stockholders, striving to please both, swaying back and forth, first on one side and then the other, like a tight-rope walker. Faithful, honest and industrious though he was, he suffered all the tor- ments of & small man in a great place, end sought to conceal his littleness by essuming a dictatorial manner toward those whom he thought his inferiors. He was fretful and.peevish with his subor- dinates and discourteous to those who would have been his real friends. He dreamed of the things he would like to do, and did the things that the self-interest of the moment bade him. In the eyes of Shuttle, Bannerton was an impractical end somewhat flighty young man who could occasionally write fairly well; of this rating Bannerton was fully conscious end took no pains to disabuse the other. Shuttle was a little man, bald-headed, with sharp features and restless eyes. Jonathan Fluttery was intellectually a cross between Jeems Yellowplush and a down-East school marm. A smile came to Bannerton's face when his eyes fell upon the angular figure of the editor of the Epinning Wheel. Fluttery always amused him; his editorials amused him, and even the Spinning Wheel itself never failed to be & source of amusement. It reminded him ofttimes of the Vicar of Wakefield trying to be a devil of a fellow. Fluttery had, lke Benjamin Franklia, whom he ‘was never tired of recalling, riseh from a printer's case, and, to use a term of the craft, all his original ideas could have been expressed by em quads. When poii- ticians of Bidwell's set, in figuring up prospective support, came to Fluttery, some one always epoke and sald: “Oh, he’'s all right.” And he was, just as right as the checker you put down and move about in a game. But Jonathan did not really belong in politics, for his ambiticns led in another direction. He was a mem- ber of the literat! of the city, spoke orig- inal poetry at banquets, and—but Ban- nerton checked himself in following this interesting character and turned to the more serious business of inspecting the trio of politicians whom Bidwell had brought to Mrs. Warrington's home. Bannerton never saw David Thorn, the Mayor, without & feeling of awe; awe at the magnificent effrontery that had thus far carried him through. Tall and straight as en arrow, he was & magnifi- cent looking man, having & grand and moble carriage. His well-shaped head was poised like & Greek giadiator's, his eyes fiashed s if reflecting the light of a proud and lofty spirit within; -his fea- tures were regular, the forehead high and the nose straight and thin of nostril. He wore & mustache and a long goatee, which gave him a distinctly fierce and martial mien. His clothes were of the very finest material and the latest pat- tern and he was never without cane and gloves. ‘When Bannerton first Thorn he had said to himself: “There’s a llon.” Later he made a discovery that caused him to efface his first impression and laugh soft- iy to himself. He had found the key to Thorn's character, the fatal defect that stamped all the man’s bold pretensions as counterfeit. Bannerton had looked behirid the goatee and found a chinless man. To- might the Mayor was in his glory, for it was the ambition of his life to attain so- clal distinction, and he was wedk and wvaln enough to think that this opportun- ity of meeting Mrs. Warrington in her own home would resuit in & permanent acquaintance. Edward Tubbett was the Mayor's com- penion and posed as his guide, counselor end friend. He was a short, stout man, with fat, wagtle-like jaws, a red face and & coarse mouth. As occasion demanded be was either & prominent young busi- mess man or a saloon politiclan. To-night he assumed well-bred ease by the simple expedient of putting his hands in his trousers pockets to show himself thor- oughly at home in evening dress. Bannerton was aroused from the reverie into which he had falien by a slap on the back and a voice that greeted him n loud tones and with a jerky manner of speech. “‘Hullo, Bapny, old chap. When did you Blow In?" Turning, he beheld the Hon. Cornelius Moran, president of the Common Councll, + % Maurice Thompson’s B;st Book Costs but Fifteen Cents. in all the giory of cvening dress. “Well, what do you think of me in the ‘spike tails? 1 don't dare to move around much for fear some of the old guys here will take me for a waliter and hand me money. You know that would be bad for an alderman. They never take coin.” “Oh, I guess you are poor,” replied Bannerton, at once adopting a manner of speéch to fit the person if not the oc- casion, a trick that had become second nature to him. *“Even the Mayor isn't in it with you to-night, Connie.” “Don’t stack me up beside that' re- turned the little politician, with a depre- catory gesture and a nod of his head in the direction of the Mayor. *“He always reminds me of a barber who had found a lot of money.” “He is your chief, and what he says goes,” observed Bannerton. “Not for Connle. It was he that tossed us all in the air on the ordinance iast winter. If he had stuck, it would have gone through all right, and the good fel- lows would have got what was coming to them. But it will be pegged up this time so hard that he won't count, veto or no veto.” “It ought to go through this time all right,” said Bannerton, concealing the surprise he felt at this blunt statement concerning the programme in which he had such an interest, and of which he, as vet, knew so little. “‘The sooner it comes up the better. When will the resolution be introduced in the council?” “What are we here for?” demanded Moran. “Do you think Henry is giving us this spread for his health? 1 guess we'll find out all about it to-night. But I'm glad to see you with us. You were a Jittle on the knock the last time. Here comes me old college chum, Himmell Hear me hand out a few hot ones to him. I've got one of his long-winded. communi- cations from the commission hung up in my committee.” But Bannerton did not wait to enjoy the encounter between the Hon. August Him- mell and the fine little bit of a man who represented the toughest ward in the city, and at the same time presided over the council from the speaker's desk. The information that Moran had dropped fill- ed Bannerton with misgivings, and he would haye given a good deal to have been safely away and relieved from at- tending the coming dinner. He had no mind to participate in the council of Bid- well and then betray him, and he resolv- ed, if the opportunity arose, to express his sentiments concerning such legislation as he knew Bidwell and his company de- sired to obtain from the city. He was determined not to be tricked into a false position by a bowl of soup, a toothpick and a glass of wine. When dinner was announced the guests teok leave of Mrs. Warrington and Edith in the drawing-room, for it was one of the pleasing customs of the city that that on such occasions the ladies remained behind: the antithesis of the good old English custom, that had its uses and abuses, but had at least the merit of keeping the men to some degree sober until they had laid a foundation of food. As the guests passed into the din- ing-room Bidwell met them 'and assigned them to their places, and it did not escape the watchful eyes of Bannerton that Shuttle was given a place on the right hand of the host, while Ledlow was seated next. Mayor Thorn had the other end of the table, so that Bannerton at once knew that there would be a head de facto and a head de jure at that dinner. As if shrewdly surmising that some of his guests would be susceptible to a display of wealth and elegance, the table deco- rations were elaborate and in keeping with the repast that followed. A stiff and formal affair it was at the begipning, but, thanks to Bidwell's address and the wine, which came very early and was served with a free hand, the ice was broken. The Mayor soon announced him- self as the great, shining light he aspired to be in the national affairs of the Demo- cratic party; Jonathan Fluttery fell to discoursing on the necessity of a firm policy in the Philippines, from which he advanced by easy stages to_the conteh- tion that in mo other country but the TUnited States could a poor but intellec- tual young man raise himself to a posi- tion of great honor, in proof of which he was ready to cite Benjamin Franklin and himself as shining examples; Au- gust Himmell edified Edward Tubbett with a symphony on the art of planting trees and fertilizing; while Bannerton listened to Connie Moran's recital of an adventure that might have graced—or dis- graced—Roderick Rapdom. As for Bld- well, he was busy with Shuttle and Led- low in a discussion; there was not a word from him as to the subject of the gather- ing and Bannerton wondered wnen it would come. ) It was August Himmell who at last pre- cipitated a discussion in which all took part. The Mayor had just delivered him- self of a well-rounded and flowery sen- tence in which he declared in favor of a strong and decisive policy in the man- agement of public affairs, when Himmell cried out: “Well, I will tell you, Mr. Mayor, if you had practiced what you preach, we would now have a 4-cent fare in this city. There was no reascn why it shouldn’t have gone through. Just because a few busybodies shoyted and cut up and made a noise, that wds no reason why it should have been dropped and withdrawn. I, for one, am in favor of having the thing brought up again.” Instantly a silence fell upon the group. iy dear Mr. Himmell,” replied the Mayor, with a lordly air, “allow me to say that Rome was not bullt in a day. Some things require time. I have pledged the voters of this city that I will give them a 4-cent fare, and I intend to carry out that pledge before I retire from of- fice. In dealing with the public it is sometimes Wwise to use judgment in these matters.” “The public!” cried Mr. Himmell ex- citedly. “What has the public got to do with it? This talk about the public makes me sick. I say the public be damned! Who is the public, if we are not the public? We, the business men and taxpayers, we are the public, and we should decide what is good for the city. It has always been the e, and If you should study history, as I have done, you will find that I am correct. Whatever has been done for the public has been done by men who know better what was wanted that the public did. I am down on the ‘public’.idea, and the less we pay attention to the public the better off our city will be.” “That's no lie,” observed Connie Moran, nodding approvingly at Mr. Himmell, who had grown very red in the face, and was shaking his head in a savage manner. “While I do not entirely agree with what his Honor the Mayor and what the Hon. August Himmell have just enunci- ated,” began Jonathan Fluttery in a thin, squeaky voice, “I must admit that the public does not always know what is for its good. I think it best, perhaps, to leave it safely in the hands of these pub- lic spirited men; for instance, the Hon. Henry Bidwell here. Perhaps he will be kind enough to favor us with a few words outlining his ideas. It is my shrewd sur- mise ‘that perhaps we will then discover why we were invited to gather ’'round the festive board to-night. He can be.as- sured that—"" *“1 beg your pardon, Mr. Fluttery," broke in Bidwell at this point, “but if you had any idea that I anticipated a discussion of this question this evening you are entirely mistaken. Nothing could have been farther from my thoughts. I consider that question buried. It was with great distress that I saw our ef- forts end in failure, as I had firmly be- lieved that I saw the end of strife in our beautiful city. Circumstances over which I had no control brought about a state of affairs which made it impossible : Al§c\e of Old Vincennes” Begins October 19th--- Complete in Three Issues for us to proceed. I think, under these circumstances, that Mr. Himmell is in error in holding the Mayor responsible. There was, 1 believe. considerable news- paper opposition at the time, which § have no doubt was based on what was considered proper grounds. In addition to this' the business men of the commu- nity formed an erroneous impression and were, to say the least, lukewarm in sup- porting what 1 considered a very com- mendable measure.”" “In reference to the newspapers,” said Shuttle, “Mr. Bidwell has undoubtedly hit The Watchman, as well as some other papers of the city. I can only say that The Watchman simply reflected public sentiment at the time. A large number of business men were very much op- posed to the ordinance, and I recefved any number of letters protesting against its passage.” “If you had received an equal number urging its passage, would vou have urged its passage?” quickly asked Bidwell. “That would be a question for calm consideration,” replied Shuttle, evasively. “If a clear majority of the people really favor some project in municlpal affairs, 1 deem it the duty of a newspaper to advocate the wishes of such a majority. The pablic—"" “There you go on the pub'ic again,” cried Mr. Himmell, excitedly. ‘‘What has the public got to do with it? Alwavs the public, always the public! Who is the public? I have got four hundred of the public working for me. What. does it count what they think? When I go down to my factory I think for them. I think for four hundred of the public. Let the business men decide these questions, be- cause it Is a question purely of business, and nothing else.” “The business men were against it, Mr. Himmell,” replied Shuttle, with a little heat. “If I-remember correctly, you your- self were not in favor of the ordinance,” “Wellgwell, that may be,” replied Mr. Himmell, sputtering a little; “there were some changes that I wanted, but I did not want it killed entirely. 'Now that I have looked into the matter more, I find that 1 was wrong. 1 amgnot ashamed to admit it, for once In my Mife.” “What do you think of the question, Bannerton?” asked Bidwell, suddenly turning to the yeung man. He was the only one of whom Bidwell was not sure at that time. .“It is my opinion,” replied the young man, coolly, “that all such matters should be submitted to a vote of the people.” In spite of Bidwell's smiling face Ban~ nerton saw the gleam in the wicked eyes. But he did not quail as he looked up at the end of the table. “There are some things,” began Jona- than Fluttery, who was now somewhat flushed with wine, “there are some things which, in the opinion of men who have deeply studled a system of government where universal suffrage is the rule— there are some things which, as Benjamin Franklin says—as Ben Frank- lin says—there are some things, as Franklin says—what the devil did Ben- jamin Franklin say?”’ “It's a long time between drinks,.John. That's what Franklin said,” cried Con- nie Moran. When the laughter which greeted this sally had subsided, the Mayor ruffled his plumage, and, addressing Bannerton pointedly, said: “My young friend has evidently been reading the Populist platform. It is what is known as the ‘Referendum,” one of those vague and shadowy ideas that can never be put into practical use in this country. If there were such a thing as the ‘Referendum’ in this city, or in force in this State, I pledge you, gentlemen, on my word of honor, that I would never as- sume the responsibilities and cares of office. If every important measure were left for the rabble to decide, if the crew is to steer the ship of state, I ask you, gentlemen, what honor would there be in being in command?” “I had ne intention of precipitating a discussion when I frankly gave expres- sion to my ideas on the matter,’ replied Bannerton, “and all I have to say is this: If you are going to have a government by the people, have it. If not, the sooner you establish some other form the bet- ter. At least, let us live up to what we pretend, Make it a government by busi- ness men, if you choose. I have no doubt but that, if it were fairly administered, it would be for the general good.” “That is anarchy! That is anarchy!”: shrieked Mr. Himmell. “That is the kind of talk that is making anarchists in this country, and I am surprised that any gentleman should come and be a guest of Mr, Henry Bidwell, and—" “I beg your pardon,” interrupted Bid- well, nothing loath to have the oppor- tunity to end a discussion which had taken a form that was extremely dis- tasteful to him; “I beg your pardon, Mr. Himmell, but I do not believe that Mr. Bannerton had any intention of offending any one. This is purely an informal dis- cussion of a public question on which any person has the right to express his views. It is,” he said, pausing, and glancing about him, “‘entirely foreign to what we are here for to-night. Perhaps I should have announced the object of this gather- ing earlier in the evening. I will do so now. There are at least some things which it is essential the leading ecitizens should take hold of without consulting the public, and I believe that when I ex- plain myself a little further there will be no dissent from this statement. We must all of us, at times, take up the bur- den, sacrifice our private time for the public good, and advance the city’s inter- ests in lines wherein the public could ac- complish absolutely nothing.” “That is exactly what I have sald,” in- terrupted Mr. Himmell. “Yesterday I received a letter which T am sure you will all hear with pleasure,” continued Bidwell, oring the interrup- tion of Himmell. "{s the consumma- tion of efforts made by me while in Washington, and it Is one reason why i am back here.” He paused a while, and, looking up amid a heavy silence, continued, “‘Gen- tlemen, I have the honor to announce that the President of the United States has accepted my Invitation to visit our-eity. This announcement was greeted by a burst of applause and Jonathan Fluttery was at once on his feet, glass in hand, to propose a toast. o“éen‘t‘lemen." he cried, in his shrill, squeaky voice, “I propose that we now drink to the toast of two of the greatest men of this—" “Excuse me, Mr. Fluttery,” broke in Bidwell, “but I have not finished. The reception of the President of the United States in our city is a matter on which we must all pull together. There must be no politics in it and no personal feel- ing. Whatever wounds have been made by party, personal or business strife must be healed. It is essential that a strictly representative committee should have charge of these arrangements, and it is for this reason that I have called you together. It may have been presumpt- uous on my part to select the committee, but 1f it Is so thought I hope vou will pardon me. This committee represents three great elements in our city—the busi- ness element, the civic branch of our gov- ernment, and last, but not least, the press. Gentlemen, I await your pleasure.” ‘With this Mr. Bidwell resumed his seat, At once Jonathan Fluttery was on his feet again, glass in hand. “Gentlemen, I propose that we now drink a toast, and that we drink it stand- ing, to two of the greatest men that this country has produced, the President of the United States and the Hon. Henry Bidwell. What one has done for his coun- try the other has done for his city. Gen- tlemen, I propose the toast.” All rose and the toast was drunk. “Gentlemen, I wish to assure you that 1 deeply appreciate the honor,” sald Bid- ‘well, after they had resumed their seats, “but it is getting late apd perhaps wo can transact a little business here. course, there will be a chairman, and it is necessary that-one should be selected at once."” “I nominate Henry Bidwell for chair- man,” cried Fluttery, bobbing up again. A cloud passed over the face of the Mayor, but he made haste to say: “I second that motion.” I thank you, gentlemen,” returned Bid- ‘well, smiling, ‘‘but under no circum- stances can I accept the chairmanship. My position in politics has been such that the cry of partisanship would be raised at ence. 1 believe this is a matter where there should be no party politics of any kind. The President of the United States is to come to our city, and it behooves us to give him a weicome befitting his Position. I have given the matter con- siderable attention, and if you will allow me, I would suggest that Mr. Samuel Elliotson be selected as chairman of the committea.” The selection of Elliotson by Bidwell Was a surprise to every man at the board, but no one expressed any disapproval. Eiljotson was a man of culture and a business man at the same time. He had Opposed Bidweli's schemes on varlous oc- casions, and it was generally known that they were hardly on speaking terms. His selection under these circumstances was an earnest of good faith on .the part of Bidwell which no one could question. But In naming Eiliotson Bidwell had made a shrewd move. It was the only way in thlth he was able to avoid naming Mayer Thorn as the chairman of the commiticc. It he, Bidwell, could afford to have El- liotson at the head of this committee surely the Mayor could make no com- Plaint. Bannerton smiled to himself when he saw what a clever play Bidwell had made. It met with the enthusiastic ao- proval of the unsophisticated Shut- tle also. who, made haste to con- gratulate = Mr. ' Bidwell heartily on his generous choice, at the same time sny'ins a few words In praise of Mr. Elliot- son's public spirit and high character. The champagne had been flowing freely, and, as it will loose the tongues of the wise as well as of the foolish, the friv- olous, and the dignified, there was soon a babble of conversation at the board. The Praises of Bidwell were sung right and left, up the table and down the table, and back again. Even Shuttle, who had good cause to suspect Bidwell by reason of dealings in the past, grew enthusiastic and remarked to Ledlow: & “It is no use talking, if we had more men of this kind it would be greatly to the advantage of the community.” Having more purposes _in view than scme of the others who had attend- ed the dinner, Bannerton had partaken very sparingly of the champagne and, as @ result, his wits were keen and his ob- servation alert. A number of toasts were drunk. Jonathan'Fluttery, now much.be- fuddled, delivered an oration; and finalé 1y, Mr. Connie Moran, being also some- what exhilarated, started to sing a song, at which Bidwell, seeing that it was time to close the festivities, arose from his u;t to indicate that the dinner was at an end. 5 :I’!annerton made his way to Bidwell and said: “I would suggest, Mr. Bidwell, that some writer of higher standing in news- peper circles be selected for this com- mittee in my place.” “By no means, nothing of the kind,” replied Bidwell. “You are on the com- mittee, Bannerton. I want you. By the way, I wish to congratulate you, on what you said to-night. While I do not agree with you entirely, I still have the ut- most respect for a man who will frankly express his opinfons, I have no use for a man who is afraild to tell what he thinks.” It was Bidwell's code that a weak op- ponent remafned still weak if you won over him, but with a strong adversary, ‘when you won him, as Bidwell generally did when he sat about it, he knew that he had won one on whom he could de- pend. § Bannerton found’ Moran engaged in an altercation with a cab driver on the street when he came out. “‘Here, jump in,” cried the president of the Comimon Council, “get right in my coop, Banny, old chap. This lobster of a driver has been sitting here since 9 o'clock, and is trying to charge me by the hcur. TI'll take his license away if he - don’t back up.” CHAPTER VL THE SEQUEL TO THE OARSMAN'S BTORY. The cab in which Bannerton and Con- nie Moran left Bidwell's party did not take either of them home. By order of the Alderman they were driven to an all- night saloon, where Moran had the double pleasure of buying and drinking cham- pagne; for buying wine is one of the favorite diversions of men of Moran’s class, and produces an exhilaration much greater than merely drinking it. It was ;&vl‘::ture of the modern beggar on horse- ck. The presence of Bannerton 'at Bidwell’s dinner, where the guests had so evideutly been carefully selected, left no doubt in Moran’s befuddled mind that Bannerton was now to be counted on as a friend and an ally. He accordingly took pride in telling all he knew, to show his own finportance in the conspiracy, and Ban- nerton, by feeding his vanity and pre- tending to disagree with him on some of the details, had no difficulty in securing the full measure of the plot so far as it involved the securing of the Aldermen of Moran's coterfe. To do this he was com- pelled to drink his share and be convivial in company in which he would have died rather than have been seen by Edith or Mrs. Warrington, for, gloss it over as much as our modern writers may, the frail creature of the bagnio is now as much the boon companion of roystering men of high and low degree as she was in the days when James Fox was both a rake and Prime Minister of England. So Hugh arose the next morning with a splitting headache and shattered nerves, and it was in no happy frame of mind that he dressed and after breakfast re- paired to his office to think over the ‘events of the previous night. In Banner- ton, too, there was a change making itself felt; a change that caused him to take a more serious view of life, to look squarely at what he saw about him and to call things by their right names. He had a keen and instinctive hatred of hypocrisy and a natural love .of truth, and the curiosity which led him to look into the street rallway ordinance some months since had resulted in discoveries which filled him with pity for some, and scorn and contempt for others. Every fiber of his nature protested against men making away with rich booty by cunning deceit, with no risk to themselves, while the very ones who suffered the most were complaisant, or even applauded the rob- bers. He had a frank fondness for Robin Hood and Francois Villon, and of all men he most cordially despised Samuel Pepys. From what he had learned from Moran he was now certain that Bidwell, with the Mayor as his tool and ally, was ready to make another dugernte assault upon the pocketbooks of three hundred thou- sand people, and against that method of attack he was ready to rebel. Had Bid- /well come boldly out, seized the City Hall, and proclaimed himself a baron come to levy tribute on the burghers, he would in all probability had in Banner- ton a dashing lieutenant. ‘ But Bannerton was a singular mixturs of strength and weakness. others he kept faith, but with himself he was forever making vows and breaking them; his past was paved with good resolutions of what he would do for him- self, over which he had trampled to do for others. With an ambition some day to write a good book, he had studied books and had read men, was “'no use to argue it further. * “Well, that is not a bad idea,” re than one class, and knew the eth- ics of the barber as well as those of the banker. But having once secured mate- rial; he lacked steadfastness for the task of weaving it into a finished fabric. The events of the present were ever proving more attractive than those of the past; each day unfolded a romance of fact that to him was far more Interesting than his fiction of the day before. What to others was the commonplace of life became to him a world of romance, a comedy or tragedy, in which he loved to play a part. no matter how humble it might be. But the time was passing when he could hope to accomplish anything in the career which he had marked out for himself. With a love of hunting, fishing, and a life In the woods, he had idled away his summers only to waste his winters in the varied diversions to be found in a city: he had laid by no money, but was blessed with sound health, and sinews and mus- cles seldom found in one so slight of build. Book after book he had begun with enthusiasm, only to drop it at end of the second chapter, and each time he came with an excuse which made him proof against all the well-meant taunts of Hannum, who had an honest wish to See the young iuan succeed. And then, after each failure, he had begun anew, with flery zeal, and a resolution to go through his new journey into the realms of fancy. He had even now nearly fin- ished the fatal second chapter of a work which he had blocked out, and which Bave promise of developing Into a story worth the telling. But as he sat at his desk now, he knew that it was to be put aside, . In vain he argued that he had nothing to gain and much to lose by involving himself in the struggle he saw impend- ing. Self-interest shrank back abashed before what he regarded as his duty. his honest feeling rose within him and set fire to his indignation, and he knew that the real drama before him would efface from his mind the mimic one he sought to chronicle. In a last effort, but with something lika a smile on his face, he drew a roll of manuscript from a drawer of his desk ‘and spread it before him. How common- place it all seemed compared to the events In which he had even thns far taken part! The dinner of Bldwell, the impending visit of a /President as an ad- Junct to a scheme of robbery, the seamy- \slde revelations of Connie Moran. It was The mimic must glve way to the real, even if, in the language of Bidwell, there were “no dividends” in the latter. So he foldel the Mapuscript agaln, wrapping stout twine about it, which he tied, with grim resignation, in a hard knot. It was a restless day for Bannerton, and his humor was not improved by a Vvisit from Commissioner Himmelil. The commissioner came down to sput- ‘der, making mountains out of male-hills, dnd grating on the nerves of the younger man with an incessant chatter. “Well, well, Mr. Bannerton,” he ex- claimed, after he had frittered away halt an hour, “you were very lucky indeed to be present last evening. That will be one of the memorable| events in your life. You are also very lucky to have Henry Bidwell for your friend. I will tell you, confidentially, that he. spoke to m=2 very highly of you last evening. Well, that was not exactly necessary, but I will be frank with you, and say that it goes a*sre;t ways with me. He is one of the few great men in this city, and we stchandt together.” /Bannerton expressed his deep apprecia- tion of the value of Bidwell's friendship, and at the same time smiled at Bidwell's cunning in thus conveying to him a re- igder of his influence and his disposi- tion to be his friend. For Bidwell knew immell to be a veritable phonograph, in- to have it repeated. ‘*Are you sure you have written those letters that I told you about?” asked the crmmissioner. *“Well, it is very strange t there have been no answers. When- ever I'write letters they are always mptly answered, and when others rite them, or say that they do, the an- swers are a long time coming.” “l wrote the letters, as I told you,” snid Bannerton, with a little vibration in s voice that he could not suppress. . There, there,” cried Mr. Himmell, here you go again. You are so high- spirited that I cannot say a word but u flare up. You make me nervous all - “I am sure I did not mean to say any- thing out of the way,” said Bannerton. “It-is not o much what you say, Mr. Lannerton,” answered the great man, bobbing his head up and down like one Of those Japanese dolls that take their n‘mllve power from the earth's vibra- tions, and are never still; “but it is the way you look. That was what caused me to reply to you last evening. I know you are not an anarchist, but when you -spoke last evening you looked like one. Well}I did not intend to speak about that bere. I prefer to argue that question when we are again on an equal foot- ing, for here I am a commissioner and you are the clerk of this board.” Bannerton bit his lip, his face reddened a trifie, and then he smiled; he had grown to take Himmell as he did sloppy Weather—an unavoidable evil, a part of the climate in which he lived. “There are very few who could hope to get the better of you in an argument, commissioner,” he said, changing his tone. The effect was magical. ““Well, that is where you are correct, Mr. Bannerton,” exclaimed Mr. Hlmmell: drawing himself up. *I have argued with riend, es. The fact that he invited you to present confirms the estimate that I ave of you, But I would like to ask our advice on a little matter. I am hinking of having the President come to my house when he is in our city. Even if he were to save his entire salary for Lis whole term he would not be as rich a man as I am, and when he was in busi- ness for himself I gave him time once, ‘which I will recall to him." ' “An excellent idea,” sald Bannerton, coolly. ““You could have the thro; : brought down for him.” S claimed the commissioner, beaming on ;xl; humble servant. “That was kings of Bavaria.” oy It was late in the afternoon commissioner took his deputun‘,’hlfiul:: Bannerton limp, and yet with his head clearer by reason of the mental gymnas- tics in which he had been compelled to indulge. ‘And this Is what they call F Job!" ™ he exclaimed, with a huzl: u“h‘: threw himself back in his chair. “Some of the men who have been hanging around after this place would last about & waeh s Despite these reflections Bannerton had no cause to complain of the Hon. August Himmell. Most of the time the pompous and vain old fellow was a source of de- light and amusement to him, a human kaleldoscope merely to be shaken up in order to show new and wonderful phases of character - jumbled together. The afternoon sun was now stream- ing on his desk, and he closed it and went to the artist's studio, where he hoped to meet Hannum. He found the painter hard at work 6n a new Idea, for Laurenkranz was as fickle as Bannerton himself. “Sit and wait,” sald Laurle, in his soft, Jerky way. ‘“John is coming. I saw him this noon.” ! Bannerton threw himself on a couch, The life and beauty of nature were all about. him—the mounted Indian of the plains, the half-wild tobacco, the wide Ot versed in the manners and customs of Stretches of prairie with its clumps of bunch grass, the waters of the Platte, and the wonderful golden sunshine of the ‘West—all put on canvas by the art of the quiet man who bent over his easel near the window. And what was his recom- pense? mused Bannerton. To live in a garret-like room, far up in the top of a building, to eat the plainest of fare, and to wear coarse apparel. “Ah,’ thought Hugh, “that is what the world thinks, but I know better.” For he knew the blame- less life of the artist, his love for his work, his peace of conscience, the purity of his thoughts, the beautiful world he had made for himself and in which ne liyed—something that no money could buy. The peace and quiet of the studio were soothing, and Bannerton, wrapped in a robe of fancy, dropped off to sleep. The coming of Hannum awoke him, and ha sprang up, eager for talk. With hard- ly a preliminary word, he plunged into the recital of the events of the previous evening, the Presidential dinner, the speeches, and the disclosures made by Moran. The lawyer listened to it all with- out a word of comment, sitting in a chair, his chin supported by one hand and the other toying with his watch-guard. When the younger man was exhausted and stopped from sheer want of material, Hannum spoke: “Well, what of it?” “What of it?”" cried Bannerton. “Why, John, it means that they are going to try again. 1t means that there is a great conspiracy by which the people of this city are to be defrauded.” “And what do you propose to do about 1t?” asked Hannum. “I propose to do what I can to prevent what I consider a great crime, a great abuse of ill-gotten power, a prostitution of free government!” cried Bannerten, pausing In the center of the studio and raising one of his hands in the alir. “Ha! It is good!” exclaimed the artist. “If you could stay in that pose I would paint you, Hoo. I would call it David going to fight the gilant.” “Yes,” sald Hannum, when the laugh was over, “and you could follow it with a picture of David when the giant had finshed with him. The result of that fight between David and Gollath was the great- est fluke on record. It was one hundred to one on the giant, and it was won by a chance shot. It has made men over- match themselves ever since.” “But David won, just the same,” said Hugh, doggedly. “There is a tradition that a lamb once killed a butcher,” returned Hannum, “but the precedents are not on that side of the case.” “So you would have me sit down and see this thing go through without lifting a hand to prevent it, would you?”’ ex- claimed Hugh. “You would advise me to be a coward, and shirk what I consider net alone my duty, but the duty of every citizen of this city. I tell you, he continued, his voice rising and his eyes flashing, “I am sick and dis- gusted when I see the subserviency to men like Bidwell and Sprogel on all sides of me. Men who should be free and outspoken by reason of their wealth and position in the com- munity are dumb through gross igno- rance, or silent by reason of a fear as baseless as it is desplicable. Talk abaut the old-time groveling of the poor before the rich! It is not to be compared with the new cringing of the little rich before the great rich. It is no longer the class ruling the mass; it is a few in the class who have combined business and politics ruling and robbing men who are their betters In everything that goes to make the world advance.” “So you have turned anarchist, have to which one had simply to talk in order. you?’ observed Hannum, laughingly. “The remark is unworthy of you,” cried Hugh, ignoring the joking tone in which the lawyer spoke.. “Yes: I am the kind of an anarehist who believes there is nothing finer on earth than a rich gen- tleman, cultivated, honest, and Inspired with a knowledge of the responsibilities that riches bring; and that there is noth- ing meaner than the man who is rich and bas nothing but money. That is tne kind of an anarchist I am.” “By what right do you set yourself up to judge?” returned the lawyer, now roused by the warmth of Bannerton's mannes. “You may look at a thing from one standpoint, and I from another. These men want an ordinance that will protect them for the future; and, as they may look at it, there is nothing unreasonable in the measure.” ““You thought the other ordinance was unreasonable,”” returned Bannerton. “You sald so at the time. Moran tells me this new one will be even stronger.” “That was merely my opinion,” an- swered the lawyer. “It has been recently well said by a great jurist that ninety per cent of the cases decided by the su- preme courts could have been decided just the other way, and yet there would have been no great injustice done.” “Oh,- John,” cried Hugh, “you are a lawyer—a corporation lawyer. You can prove by words that the moon is a green cheese, and get me to agree with you. And after I have done so, you can turn around and explode your theory. You have made me agree with you on propo- sitions and later, when I expressed the views you had made me accept as fact, you have turned around and proved that I was right in my first opinfon. You have done it dozens of times, just for practice.” “Then there is not much use of arguing further,” replied Hannum, laughing. “In the first place, I do not believe the ordi- nance will be brought up at this time. Bldwell is on his last legs, politically, und the public sentiment is too strong against any measure of the kind. You have built up a theory and feel bound to stick to it. In the second place, if It does come up, it will be beaten In the Coun- cil by reason of the pressure brought to bear on the Aldermen, who cannot all be controlled by right of purchase. In the third place, the courts would afford all the mecessary protection, I cannot see, then, the use of getting worked up over the matter. Take my advice, Hugh, and let affairs of this kind take care of them- selves. You are not in a position to mix in them. By a word, Bidwell could make it unpleasant for you.” “If i thought—" cried Hugh, breaking in, and then suddenly coming to a stop. “But, pshaw, John, what is the use of our keeping this up? We will walt, afd see which of us is right. Iam pessimistic with an optimistic temperament, and your optimism is that of a cynic.” “Your only trouble is that you have Bidwell and Sprogel and Ledlow swelled to too great proportions. They are not so much as you think they are. I have met them twice myself, and I did not have to get off the track. They are good bluffers—that is all.” “Well,” remarked Hugh, “a bluff al- ways wins, if nobody calls. “I give a damn for it all!” suddenly <broke out the artist. “It is all old stuff that you talk. Hoo Is the anarchist, the peasant, the little fellow: John is the corporation, the rich, the baron. Some time you must fight each other In earnest. Put to-night we go to Suddermann’s-on- the-River. The moon comes out early, snd when you look at the moon shining on the water you forget everything ex- cepting your sweetheart.” The words of the artist, “Some time you must fight each other in ea: 3 rang in the ears of both Bannerton and Eannum for an instant, and each shot a glance at the other, which each at- fected not tofln;ucc. “Laurie is right,” Bannerton saild. * will be a beautiful night on the river, .:; the breeze will do my poor head good. kave a katzenjammer.” = “And yet,” sald Hannum, “you and Laurle will' persist in telling me what I miss by not smoking or drinking.” “John,” observed the younger placing a hand affectionately on man, his . little landing near the big bridge, friend’s shoulder, “sometimes I think you are too good to be true.” Bannerton had a way of saying thln(s’ that were not to be answered. The three men rode in an electric car, crowded into a narrow seat with other men hanging over them fore and aft. It was no place to talk and each was busy with his thoughts. They took a boat at the and Laurie appropriated the seat in the bow, while Bannerton established himself In the stern. “I like that” exclaimed the athletic lawyer in feigned protest. ‘“Who sald I was to pull you fellows up the river for two miles on a warm evening like thig 2" “That is what you get for having been a great oarsmanin your day, John," said Bannerton. “You have talked about your work, and now you must demon- rate.” have not pulled a boat for a long time," remarked Hannum. “It may be that I have forgotten. “Oh, it is not so long,” observed Hugh, carelessly. “Let my bright talk take the place of bright eyes to encourage you.” Hannum laughed ag he dipped the oars into the water, and with a sturdy pull sent the light craft Into the stream. He laughed again as he said: “The/ beauty in you, Hugh, Is that you stumble’ along pretty close to facts of which you know nothing.” “The heauty of it,” returned Hugh, “is that when some people think I am stum- bimg I am really picking my way most carefully. Wake up, Laurie, and listen while I tell a little story. It is the fable of the woman-hater who didn't practice wbat he preached when there was a woman in the case—or, more correctly speaking, in a boat.” “Go on,” sald Hannum, “and while you are at it, the dribble from the oars will play an appropriate accompaniment.” “Once upon a time,” began Bannerton. “Are you listening, Laurie? This is for you. I do not expect this crusty old bach- elor, who detests all women, and actu- ally hates girls, who sneers at chivalry, and who holds the whole female sex degenerate, to pay any attention. Well, once upon a time there was a girl who went out in a boat with a young man wHho was not intended by nature to bend an oar or strain an oar-lock. The wind came up—it blew, and then it blew. The anemic young man and the blooming grl were driven on a pebbly shore. Now, at this particular spot there stood & well- preserved gentleman of middle age, who watched the wreck with a cynical smile on his face. To have offered any assistance to the effete sprig of the moneyocracy and his frivolous companion would have been directly contrary to his whole code of ethics, and he fully in- tended to walk calmly away after he had enjoyed the complete humilfation of the pair. But just as the boat grounded on the sard he was seized with*an impulse, and before he knew it he was wading out in the water to the rescue, thereby wet- ting his neatly creased trousers to the knees. With no gentle hand, he pulled the young man out of the boat, turned it about, and, springing in, gallantly of- fered to row the fair young creature back across the storm-swept lake. The boat was one of those arks used at summer resorts, and was big enough to weather a storm in the Bay of Biscay, but the damsel wot not. ‘Nay,’ said the fair creature, ‘let me but alight, and I can ride back on the steamer.” Why risk your life for me? With a proud and scornful glance at the raging waters, our hero swung the boat round with a mighty ef- fort, and started back in the teeth of the gale. As he rowed, he heaved and bulged the great muscles of his arms and shoui- ers that he might more impress the amsel, and suddenly he burst into song, in which he—" “He did nothing of the sort,” broke in Hannum, redder in the face than was warranted by his exertions of rowing, “and if you say another word, I'll—" He stopped abruptly, ashamed of his outburst of temper. He was keenly alive to ridicule, but he knew his weakness as ‘well as Bannerton did. “Great gods and little fishes,” cried Ban- nerton, nothing daunted; 't a fellow tell a seafaring yarn without being as- saulted? I am telling this to Laurie. It is the subject for a painting. What lo you know about it, anyway?” “A man saw one of the dudes in your set floundering around in a boat. Ha wanted to get across the lake himself, so he helped the little creature out, jumped into the boat, and rowed.across the lake. There was a silly little snip of a girl in the boat, and the man didn't so much as look at her. The water took the paint and powder off her face, and—and—" “Ho, ho,” roared Bannerton, throwing himself back until he nearly went over the stern of the boat. “Paint and pow- der! That is good. You, you big, craven knight, you did not even wait to look the little snip of a girl in the face, but ran away without even giving your name. Now, sir, I Intend to present you to the Iyoung woman at the earlies§} opportun- ty.” “You will be traveling where good in- tentions are used fof paving stones befora you get that opportunity,” answered the lawyer, grimly. “‘Oh, don’t be angry with me,” eried the younger man. “Music hath charms—" And he proceeded to sing, with many variations, a topical song, each verse con- cluding with the refrain: “Thers are things that cannot be explained.” “‘Hugh,” sald Hannum, when Banner- ton had finished the last verse, “you will always be a boy.” ‘I hope so0,” replied Hugh, carelessly; “‘and you, John, will grow old and dried up. And, worst of all, the Devi) will get yer if yer don't watch out.” Again the lawyer made no reply, be- cause he was not quite sure. But the artist chuckled softly. Suddemann’s-on-theé-River is & famil: drinking resort in the best sense of thz term. In a city where the preponderance of Teut>nic blood has made beer-drink- ing a virtue rather than a vice, this great open-air saloon on the river-bank was frequented alike by the rich and the poor, the fashionables, and the ‘“community people.” And, be the truth known, the fashionables were much oftener the of- fenders against the rigid rules of deport- ment laid down by Papa Suddemann, the grizzled proprietor, than were the every- day folk who came summer evenings to drink thelr beer, to chat, and to listen to the music. But Suddemann knew ne caste, and on more than one occasion say groups had been informed that no cham- Pagne would be served, and that even the. flow of beer would cease under certain contingencies. The pavilion was large and spacious, and extended along the river- bank and out over the water. There was & house on the hill back of the pavilion, where more elaborate meals were served than in the pavilion, and a long row of sheds wherein those who came in car- riages could put up their horses. “Let us go up to the house and have a Square meal,” sald Hannum, as they left the boa‘ and began the ascent to the hill. “I am too hun; for one of your Dutch lunches, Laurte. ) “No,” replied the artist, emphatically. “That is the time to eat a Dutch lunch —when you are hungry. You eat too much, John. You can get a Wiener- schnitzel in the pavillon, and that Is enough for any one.” Laurie always had his way, because he wanted it so seldom, and the three men went up toward the pavilion. It was a beautiful evening, and the place was thronged with groups of people. As they made their way looking for an unoccu- 1 pled table, Hugh felt a tap on his arm, and heard a voice saying: “Hugh, Hugh! Where are you going?’ He turned and there was Edith smiling up at him. Mrs. Warrington and Bid- well were seated at the table with her. A walter coming down the aisle bearin, a tray filled with brimming steins block +* 4 Look Out for Future An- nouncements of Great Books. o . ] )