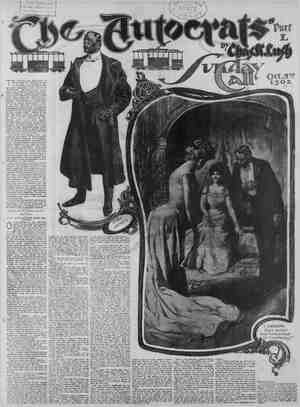

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, October 5, 1902, Page 2

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

2 THE SUNDAY CALL. w—m “True, Cousin BAaith,” returned the young man; ‘““we must respect the office if not the—the—the officeholder. Pray be seated, Aunt Kate.” “Aunts and cousins, and nephews and nieces,” exclaimed Mrs., Warrington, ughing, as she seated herself. “I won- er if such rel can be established at common law. Seriously, it is becoming somewhat embarrassing. A widow must L tions.” s, toc cried the Cousin Hugh, fare- 1 am hence- 1oy me er cousin mine g but a sister” suppose you and Hugh have been here most of the evening,” observed the elder woman; “Hugh at his old trick of tea people to pieces, and you encour- aging him in his vivisection.” We h aing our course in f human nature is much more in- we keep off the a t the lec- to- pick has manner n 2 most charming both cimen, over- said Hon- exclaimed Edith **Impos g to her face d Bannerton, he was in back!” m brow I urm heard d Mrs. Warring- er think he has I have had a with him a moment busy lance at three = days changing , his he wrote me exclaimed Edith. *I wonder what 0; go back to the old house with continue to live with you, aunty? at once. Come, Hagh,” to you must take me r me to es- the widow, it is' time great many Edith, Beside: g if a people are not to be disappointed to-mor- 16w morning “Yes Bannerton. “I prom- ised tc thing about this inter- in Hugh,” sald the har Our course of y postponed.” study is indefinitely Bannerton to him- self as he rode back to the city in an tric car. *But mine is only be- t has brought Bidwell those men in might miss it by t be thought placed it at thirty. The lat- ' He and were regu the chin H head ng type, with the one seldom £ or those who He had cy—about which he e second joint each mb. But so hands few, even e acquaintances, ever uliarity esided in this city less that time he f its affairs who had boundar- he hgd a by i in aimost w some man timate terms, ut in nce covered a wide range of liie, that what one right anotner ilege, 2 usurpa- t wledge he play . brought out his I e and waxed indignant at ung Bennerman's Jperverseness; for they were all older than he. Of his own re: s on many subjects he could argue on many ng his temper. He w g 2nd remodeling hir vet set and harden nds his guard was those who .seck the same coin; s alert in deteuse A boyish manner, ely and apparently telling things that ret, and 2 general air made a combination of g him to pursue the » which he lived. en are very much like the otice that you are , end they straightway be- was not and Jet college Bannerton on The ily paper of the nce of Bidwell, Mrs. Warring- soon raised to an ne of the younger brood to express opinions on ) one cares whether wrong. This was fol- favor which installed > the three self-made eved the commonplace distinction of ting the public debt commiseion At the monthly etings the € carefully dried h a blotter signatures of the three sioners, signed his own name to t he as dimly un- screet” hom- the prefix of older men were he gave tons as a well-treinaZ out- an mig>*. And this 1l the commissioners ~.ices, he drew his cl e born of the compensation of me from him. As he to contribute to lor derstoo age ad mission con -yship young man was plante grow, and Bidwell felt that he could bend the two twigs to suit his purpose, A MYSTERY AND A RIPPLE. The appointment Bannerton to the gecretaryship was ess and no more a mystery to Bidwell's associates than were many of his ac were dis- Those whe deep ir 5 s affaire screet seldom got ut nself had never fathomed. were, hung over and envel- His earliest recollections m house, a great, wide t sout which he roamed I where he found the pupils, and where he learned s .. ‘Then it was he née i the nameless yearning Jed his breast at tim when ed, that had made the tears come bis eves when he woke in the night— the insdnctive longing for the mother's This famous book will cos you only fifteen cents. eh love that he had mever known. His tul- tion was promptly paid; he was clothed, and presently he was allowed the small Pocket money without which many a 4 is led to the first steps that lead to dis honesty. When ready for college hé had been called to New Yors City, where, in 2 great law ofiice, he was told that there was deposited with the firm a sum of money sufficient to carry _him - through college, with the express stipulation that it was to be used only for that purpose To his appeals to he told something of himself or of the unknown fricad, the lawyer was bland but uncommunicatiy. 1L was purely a business matter for a c. ent whose name was a professional se- cret; the firm knew nothing of Mr. Ban- nerton or his affairs ana he was @ liberty to accept or declinc the money; He wisely decided to aicept it and to pide his time for finding cut somethipg sbout himseif. The day of graduatiup is & memorable one in the I of most men who have passed through ccilege. To Bannerton it became dou 0. The only thing that seemed in any way to connect him with the past was a small locket of gold, made in the form of a slipper and bearing tiie initials “J. D.” He had always had this locket and during his college days he wore it on his ch chain as a charm. At the class reception on the evening of the day of his graduation he was startled tc have a woman advence to him and say “I beg your pardon, sir, but may I ex- emine the locket you wear?” The suddenness of the request, the evi- dent air of serioisness with which it was made and the aristcratic bearing of the speaker made such an impression on the young collegian that his tongue clove to the'roof of his mouth. A thousand #nd one hopes sprung up within him, the hun- c-eds of romances he hcd bullt about himself repeated themselves in an’ in- stant and he stood transfixed, gazing &t the handsome face of the woman who was looking down at the locket. “It is the same old locket,” she sald, looking uwp. “It is marked with the ini- tials.” The eyes, the Mair, the features, the very sympathetic quality of the voice, told him instinctively that all his dreams Lad come true. He knew It was his mother. Something stronger tHan reason told him he was right. In an ecstasy he was about to clasp her to his bosom when she said: “It belonged . to your mother, Downs. 1 gave it to her.” The reaction was too great, and the Yyoung man began to laugh in a foolish, hysterical manner. “Dear me!” exclaimed the woman, tak- ing him by the arm and leading him to the door that led out into the cojllege Jeanie grounds; hard.” When the cool air struck him he re- ‘covered somewhat, and with tzars str.am- ing' down his face he begged her to tell him of his mother. thought—I thought—" “you have been studyug (wo he sobbed, Jocdness!” exclalmed the woman quickly, at ‘the®same time starting and lookiag about her. ‘‘Listen, I gave that locket to an old friend of mine, Jeane Tlowns, a girl I knew in New York many years dgo. She was the closest friend T ever bad. My name ie War ington, Mrs. Kate Warrington. If you sre indeed the &on of my. old friepd I shouid be pleasad t0 see you at my hotel to-morrow.” She took out a card and giving it ®o Bannerton said: “You had better not go back into the room. I shall be pleased to see you to- morro 3 The next day Bannerton, after a sleep- less night, cailed on his new friend. It seemed to him as if he had really founcd a mother and to her ‘he poured out the story of his life with all the frankness of youth. “It is a strange chance thai J should have met you here and that I noticed the locket,” she said, when he had finished. “I bave no doubt that you are the son of my old companion. She befriended me once when I needed help, and now I in- tend to help you. If you will come with me to the West I shall be pleased to some influences I have there to your ad- vantage. 1 cannot imagine who has helped you along and looked after you, but it is possible tkat your father still alive. 1 bave never learned whom your mother married.” Bannerton was discreet enough to ac- cept her offer—and so runs the story. “I wonder what Bidwell Is up to now?” repeated itself over and over in Bannér- ton's mind as he lcft the Watchman office and walked to his rooms. In study- ing the lives and characters of men about him he had come upon Bidwell so often as a factor in shaping their careers that he had grown to look upon him as the starting point from which to solve maLy problems concerning men and motives. And when the night was so far along that the moon, grown pale and worn, was fading In the west, and a new light was beginning to glint on the waters along The eastern horjzon, the man of whom he thought, Henry Bidwell, was paciug back and forth on the terrace overlooking the lake. In a little time, as he stood under the elm tree, the dawn opened across the water, and looking at the yellow giow that made the lake appear as a waving curtain of gold he eried, throwing up his hands: “It is too much, too much. Ten mil- Hons of dollars, and one last coup. I cannot set it aside.” CHAPTER IIL THE SLIME BELOW. Ledlow, the banker, lived in a palace fit for a prince and worked like'a slave. Ha was very tall and thin, and long bending cver his desk, sorting papers and count nz money on low tableés edrly in life had &:ven him a stoop that had rounded hs shoulders untii he looked like a giant hunchback. His hair was prematurely sray, for he was not yet 50 years old, ind his face was lined and drawn. His nouth. was small and the lips set, as of one who has had to say, many times a day and with decision, “No." ' It was not e strong face, buf it was that of the weasel, cunning and sharp. attributes that take the place of sirength until ad- verelty, the great test. reveals its ab- sence. Weazened and frail as he ap- peared, he was rea:ly a greature of iron— a glant frame of bones strung together ~ith tendons like tempered steel. Eco- romical in all things, he did not keep id flesh and bulging muscles for which he tiad no use; the food that he ate was raw ruaterial to furnish a certain amount of cnergy, as coal feeds a boiler. The bright- ness of his eyes was the only sign of health about him, but they to'd the tale of the inner works. Half a century ago this man could have wern a frayed coat, been careless of his linen and would have tkrived and - been deferred to. But he bowed to a new code. With steel-gray tousers of such close cut that the legs looked scarcely bigger than umbrella coy ers, a black frock coat, pafent leather #hoes, a high, straight coliar, encircled by a scarf of bright hue, he was the pic- ture of a high-bred business gentleman. He had even appeared at the Lake View Country Club in golfing costume, an ex- ample for diffident business men and a subject of mirth amorg young women— who were promptly reproved by their dis- creet mammas. Ledlow and Bidwell were friends. This friendship was not based on sentiment, but upon the rock of common interest, sonsequently it was enduring. BidweM criginated, planned and cerried out; Led- Iaw furnished the ammunition, looked after the heavy artillery, kept other forces off, and, frequently enough, pos- sessed himself of the secrets of the en- emy while appearing to maintain an armed neutrality. Like freebooting com- panions of old, they divided the plunder between them, Ledlow usually taking the larger share. This division was ou the kasls that Ledlow risked both his money and his reputation, while Bidwell risked iess of the one and none of the other. The evening Iflel: the “children’s party” Bidwell came to see Ledlow at his home The banker was in his library and laid aside his book as he rose to greet his ler. “S8o you are back again, Henry?’ he aald, as he shook hands. ‘“You are look- ing better. But whal brings you back now? You told me you irtended to spend a couple of years in Europe. You remem- Ler that I laughed when you told me. One trp to Europe cost me $50,000 and Lhat was enough me." Bidwell knew the trip to Europe to be one of Lediow's sore spyts and made no comment. It had cost the banker §50,000 by losing him what he thought he might lLave made if he had remained at home and been in a lucky deal that went wirough during his absence. sce you have been reading,” ob- served Bidwell, giancing at the book that Ledlow had laid aside. “I find no time to read myself and did not suppose you did.” “It 18 simply a part of my exercise,” exciaimed Ledlow. “The doctor prescribed it and 1 read half an hour every evening. Then I go to work.” Vhat is the book?"” asked Bidwell. “It is called ‘Treasure Island,’ written by a fellow named Stevenson “Some relative of Ike's, I guess,™ ob- served Bidwell. “What is it about? I like the title.” !Oh, it's gll about a couple of men, a doctor and a business man, who fitted up a ship and went to an isiand to dig up a lot of gold. They got it, too; made a big return upon the ‘Investment.” “How much did they declare?” Bidwell. “‘Several hundred thousands, I should judge,” answered the banxer. “Pooh! a mere trifle,” observed Bidwell. ‘“The original investment wasn't large,” explained the banker apologetically? “Ludlow,” sald Bidwell, impressively lowering his voice, “have you any idea that I returned for nothing? What would you think if I could show you a deal with a profit of ten millions in it?” Instantly the ferret-like eyes of the banker emitted sparks of fire. He held up a hand in warning, and rising, went softly across the -room and closed a door leading into. the adjoining apartment. There was no one in there but Ledlow's mother, oid, nearly blind and deaf as a post. He came back to his chair and, geating himself, said, speaking soft and low, for he could purr almost as well as Bldwell: “In what line is it, Henry?" “In my line,” answered Bidwell, de- cisively. “In the line of legislation. Leg- islation for the benefit of the city,” he added with a chuckle. “Street railways?”’ queried the banker, doubtfully. asked “And ‘what can be better?” well, with some spirit. done well enough so far? It gave me my start, and it has helped to build you up. Show me anything you have touched that has yielded as great and sure returns.” “Yes yes; I know we have done well answered Ledlow, half-closing his eyes cried Bid- ‘““Have we not and speak: as it to himself. “But I thought we had pressed matters as it is. What is your new plan “The extension of franchises fifteen vears, the granting of new ones to save us from future competition, the establish- ment of the rate of fare until 1950, and all done in the form of a binding contract disguised as an ordinance,” answered Bid- well, firmly “You know all that has hampered and menaced us is the fact that the courts have held that our or- dinances as th were drawn were not contracts. But this will be made In the form of a contr: With such an ord:- nance there would be no investment like it. They might put the fare down in every other city in the country, but they could not touch us for half a century.” For a time Ledlow was silent, while Bidwell watched him with anxious eyes. “I have my doubts, Henry,” he said at last. “We are close on the limits of this kind of legislation.” “That is what they are always saying,” cried Bidwell, rising and walking to and fro. “They, said the same thing ten years ago, and I told them they were wrong, and proved it, too. It is the same now. I can get this ordinance through. I am sure of it. I have looked over every inch of theé ground.” “But will the people stand it? There is bound to be trouble some time.” “The people!” exclaimed Bidwell, with A laugh. “Why, I will have the people clamoring for the passage ot the ordl- nance. I am going to give them a four- cent fare.” “What is that?” asked Ledlow, sharply. “We call it a four-cent fare. It ig the sale of tickets at the rate of six for a quarter. You know what that means.” “But what will happen when the people find out what it means?” asked the cau- tlous banker. “What can happen?’ replied Bidwell, with' a shrug and a laugh, “It will be strictly according to the law. Are we to oe blamed for making as good a bargain ar we can if we adhere strictly to the laws of the land?” “Certaiply not, certainly notS saia Ledlow, decistvely. It was his gospel that a man might drive as sharp a bar- gain as he could, no matter who suffered, provided the letter of the law was not violated. He took out a pencil and pro- cucing a pad of paper he speedily covered it with tiny figures. Then he looked up and said: “I don't find ten millions for :Alice of 011 Vingemnes,” Thustrated With Seones. From Viroinia Harmed's Great Play, Besing October + us. It is a long time to walt.” &0 no lower, and you know why. With this ordinance-contract passed it would Jump to thirty. y “How many millions do you expect te put in it?" demanded the lean banker. “Nothing of the kind,” answered the manipulator. “With a margin of a dollar you are safe. Eighty thousand dollars would yield a return of $1,500,000 when it reached twenty-eig We are in first. It Will be to twelve before a word is out.” The manner of Ledlow suddenly changed. His eyes snapped and his lips elongated, as with children and the orang-outang, when Inspired hy eagerness and greed It was o but it _aid T an instant, not escape the alert observation of Bid- well, who emitted a long breath, as if in relief. This sound is heard sumetimes at the poker tabie, and when the forem prisoners make 1t he jury rises and is mature reducing =ays, “Not guil the pressure But the banker recovered himself In an irstant. -He spoke slowly and with an of grav t. whén he said: do not like the thing, Henry. ) and I am a lLanker. t ik outright it wWo a of mar- gins is \é, as you well kEnow. give some thought &nd return a “Of ¢ » s not absolutely rertain a 1well,” cautiously, “so it m t to ‘make any move until we have c d agafn. “Why, certainly not, Henry,” returned Ledlow. “I will let you know my decision rust go slow on this, have more details.” down the street nself. He called for his n, which he had left in a day or so. V and of course I Bidweil went chuckling to niece at the re eerily to visit Ledlow, and no one was more lively and apparently free from the weight of business for the rest of the evening. But he took care to avoid being alone with Mrs. Warrington, and she no- ticed it. He worried not at all over what would be the final decision of the banker. He knew Ledlow's creed to be that a surs thing was no speculation, margin or no margin. As for Ledlow, no sooner was Bidwell out of e than he fell to figuring again. he walked back and forth, rubbing t nose, and wrinkling up his y 1ooked like a rat's. ‘It is a great scheme, and Henry is a aid ‘fo himself. "It but Henry, I would not h it. s a sure g, to a cer- ain degree. He has nevef failed me yet, and never before was he so positive.” Suddenly he bethought himself of his book. Being a man of strict method, and having paid for the prescription, he sat down, resolved to take his medicine. But somehow the book failed to take his mind away from his talk with Bidwell. How commonplace it seemed now; the chests of gold and the pieces of eight falled to thrill him as they had before. A sweeter song than ever Stevenson sung was ring- ing In his ears. In disgust he threw the book aside, and, rising, he grew in height until the great curve of his shoulders was almost straight. ‘A couple of million dollars to be picked up,” he murmured, again rubbing his nose. “What is all this tommy-rot about a few buckets of gold compared to it? And silver, too. It wouldn’t pay for the long haul. This plan of Bidwell's is some- thing like it. An exclusive franchise, and the fare fixed until 1950! It is the capture of a city, with no blood and muss about i And with this astute and humane ob- servation he went upstairs to bed, and slept the sleep of those who work hard and are tired. And this is a beginning, out of which came stirring events that moved three hundred thousand people to fight for their rights; at caused bitter hatred between friends; that cost the life of at least on man, and that wrecked the fortune of some and blighted the futurs of others. were a It was the be, ng of civic strite in which a people awoke to battle with forces secretly organized, and publicly marshaled, to enslave them—to bind them to the pa nt of tribute. And out of it also came new inspiration fot some, the awakening noble impulse, and deeds born of courage and a sense of moral right. CHAPTER 1V. “ALL KINDS TO MAKE A WORLD.™ Up in the dome of one of the big build- Ings of the city an artist had made his studio with an instinct much like that of the doves and sparrows which builld their homes in the eaves and cornices about his windows. Like his feathered compan-~ fons (for companions they were, coming to eat out of his hands, and -even ven- turing into the rooms to steal bits of fringe from the costumes that hung about the wall), he hid himself high above the city. It was in the heart of the eity, and yet it was a great way from the haunts of men. Occupants of the bulld- ing were dimly conscious that the soft- eved man with the wide-brimmed slouch hat and the closely trimmed beard was a fellow-tenant, that he had a nest some- where above the elevator, and that he was a painter. So they pitled the poor soul, and wondered why he ever got fato a business from which. he could never expect to amass the riches which they all dreamed of when they had time. And in the great dark-blue eyes of the painter none of them saw the pity with which he in turn regarded them, one and all, trom the bank president, who always rode up the one story to his office and grumbled when the man stopped the ele- vator too abruptly, to the clerks and office boys who swarmed into the eleva- tor cage in the morning to be taken to their cells for the day. For Richard Laurenkranz pitied them from the depths of his great, pure, honest heart. Often on a summer afterncon he would sit for hours at one of the windows looking over the tops of the buildings at the lake shim- mering in the distance, or lost in wonder at the new hues in the sky—for he wor- shiped the sky, God’s sky, which alone had not been touched and deflled by man —until, of a sudden, he would exclaim, with a nce at the city below: ‘“Poor fellows! They are in the dark. They live like the prairie dogs.” Born in Wurttemperg, he had early been placed under the tuition of mas- ters, and later had won by a scholarship a year's course in the galleries of Ber- lin. It was just at the conclusion of this that he, with a number of rollicking young artists, had accepted a proposi- tion to visit America and there work on the panoramas that were being painted in the new world A year with this hard- drinking, careless colony was enough of the life for him, and, with a little meney in his purse, he had fared forth into the great West to see the life of the plains. The new surroundings had = captivated hini, and it was not until two years later that Re returned to paint the cowboys and the plains as they had never been painted before. One of his large pictures caused men to stop and think at two great art exhibitions in FEurope, whither it had been sent; but no one could think of buying a picture painted by one who boldly g knowledged himself a man of the We. ern wilds. So the pictuge, with it story of the burial on the plains and the great and holy love that man may bear to man, in conception a poem and in execution a triumph of art, was sold to the widow of a rich brewer and went to adorn a house where few came who could help to herald its creator to fame. It was a gre;l pxc(\;re. and modest Richard Lau- renkranz knew it; some day ‘ will know it, too. el Between Bannmerton and Laurle (for “Laurie” he was to those who loved him) there had grown up a friendship such a ard fiction to follow. T T T ——— b Other popular works of stand- ‘f “There is no walt about it,” raid Btd= | well. “Cosmopolitan Street Ralway . Btock i{s down to eight. You know It can ! /