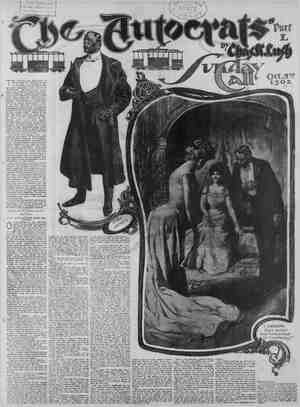

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, October 5, 1902, Page 3

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

THE SUNDAY C&LL. 8 e e n of opposite tem- one lignt, of vagaries and enthu- calm, even-tempered, 3 erton iiked lly Bar rton. patron and his cter—the because first class, rized th of hi failed to see his b in vish rhanner o the defects for which the nd contempt. fternoon of a with his , long g out tiny curls reverie be cricd gayly; “so 1 have g Painting your air ca = es on canvas? How € warn you that I = resig ger if you keep pictures painted on them,” replied the little shrug. “They matter how rich a em. culiar No of them to vered Ban- e. “You but I do. 1 ex- some r big talk, “Is it an- in it, too, 1g hand cheese in unted the artist; “then I do . beer or cheese. Your books el the second chapten Never mind, Laurie,” ecried the young ‘I will surprise you some day I will make you feel ashamed for not n ha confidence in me.” (for the life of him he Hugh anything but at it himself), when you write t in- he great picture m a b cried asping one last got I will give object in w world a great You are foolish, ing a boo! painting.” said the artist, blush- and, walking across > whistle gs of Indians adorned the wall ess these are all poor,” to himself. “Just neybags. Yes, I can let 3 for $10,600—the lit no comment, and Ban nerion, sitting down and f a pipe, t smoking. Unlike the artist, he drew and blew out great c s face growing ggestion of wrinkles and the window the Indian scalp t d gle n e ceiling; a mouse stole e c from the moccasin ahd . a rug. s broken by two light « followed by a single e re force. Both men awoke s John exclaimed Bannerton, = o his 8 stout, w i and a . - ight brown curly hair, T C n the room was T face that st teeth gleaming 1 a che that on) lines of a nd the busy man! gamble the lo as the busy T have been too fine a day put in Bannerton, n of indignation. rstand, Mr. Never- s have been at K “First or second chanter?’ asked the new gain laughing. “If it is the first of stewing ar of you, but if it is almost through with ' returned Bannerton. me tell you about the g is about to hap- 1 find out what it Bidwell has as you are means some- s mot know that ted John Han- er people cease portance to what soon drop out of s t. not command thirty ted States Senator does not W fce nnum was a lawyer, and when thing he handed it down as if decision from the Supreme n sile he honored and t udge, was in contempt of Hangum was not t a few men at the top id he was a good one, ard of him. He held a large cor- work for a s a lawyer d a great reputation for But no man ever say a word about of his chief. He neither drank nor smoked, was wise in the way of men who did both, and had - 3 v nights at B with corpora- g to-use it as a - of the great com- ) learned ko a ple buses which they 2 But he was not oumay” at times, in the the power to w eir last appeal. ice, John,’ is brow. beer beg ich men med the “I can't stand annerton, when the Jook squarely at u 2 you find them in the t of your success. But refuse to see things we know that is no sign that the nd it out. The pub- have ic does not know Bidwell as we do. And o ke underestimate his re- _ es the gullibility of the public at the same time. Eidw back with work on hand, and Is that it has something to do w er attempt to get a street T rdinance through the Common lay back in his chair and 1 are always seeing signs, Hugh,” he said. “You remind me of Leather- t dodging at a broken blade of cocking his rifle at every bent £00d,” cried Bannerton, spring- and pacing back and forth nmerv- ‘Will Be Completed in Three Sunday Call Editions. ously. “Let us continue on the same line: What were his reasons for joining the La Joie Club? Will you tell me that a man like Bidwell can find anything con- the fellowship of men like Coa- Moran or David Thorn? No. But vid Thorn is Mayor of this city and Connie Motan is chairman of the Council. i the pair, bitter enemies a short time , and leaders of rival factions, have to be great friends of late. Would genial in nie Bidweil spend a minute with either of these men if he did not wish to use them? And how can he use them except to se- re favors for the company of which he he head. They are Democrats and hz a Republican. Where js the political me you speak of? Can they place him in the Cabinet of a Republican President, or make him the tall-piece to a national ticket? “There is a bowling alley in the La Joie Club,” observed Hannum. “I was told that Bidwell was advised to take exercise. \ ‘And 1 will tell you, John,” returned Bannerton, “‘that he has taken it setting up pins in the upper rooms of the club- house, instead of knocking them down in the bowling alley. I know. Picture Bid- well with Thorn and Moran, and Ed Tub- bett and Judge Blover, and Scotty Ma- guire and Judge Delaney, and then tell that you think that Henry Bldwell ned that outfit for his health!” Hannum laughed in spite of himself. “But, after all, Hugh,” he remarked in 2 moment, “what is it all to you?” “Why, nothing, I suppose,” cried the young man, “excepting that it makes me mad to see such coarse work go through. Say, John, are the people really fools?” Mostly,” responded Hannum dry until you wake them up. Then they turn the tables fast enough and somebody s hurt.” body is going to wake them up this time if Bidwell and his gang try to go through with what I think is their programme.” “There is another end to that, Hugh. I said that when the people are waked up samebody generally gets hurt. I might add that when an attempt is made to up the people, and it fails, some body is also very apt to get hurt, Stick to 3 work of sittiug softly in the ob- servatory tower studying the earth and the inhabitants thereof.” John,” said Bannerton, “you talk but in your heart I believe you nk as I do about certain matters. I d like to see you loose and free. nnum only laughed, and, looking pictures, said: I would give everything T have or ex- to get if I could only paint as well - old friend here.” { course,” exclaimed Hugh, “and T give everything I posses and much as T expect to get, if oniy (?_‘,e ou do. I would do returned the lawyer. remember, Hugh, races are not going to the whip in the first rter. Just let me jog along.” The return of the artist put a stop to the ron of the conversation. He threw his hat to one ‘side and dropped into a chair, limp and forlorn. “Why, what 1s the matter, Laurie?” cried Hugh. “You look as if you had lost your,_best friend.” answered the artist, after a short T have lost a friend, perhaps. as a little girl. She was just ahead of me, crossing the street. She ran she slipped. A horse came and sed over her legs, That I saw.” she killed?” asked the young “Was man. “I do not know. Men came running, and then I ran awaw 1 could not lool “You should have stayed and got the name of the driver,” sald the lawyer. “You should have also given your name, so that you could be subpenaed as a wit- nes: “That is the Yankee way,” replied the paint with a little shrug. “I thought oply of the little child. You think of the money, John.” Well, we will come up and see you evening,” answered Hannum, the rebuke. : . T will stay alone to-night. 1 am {ll,” said the artist. Poor fellow!” observed Hannum, as they went downstairs from the tower “he will brood over that Jittle aacident all night It is too bad he is so sensitive.” “No,” said Hugh, “it's a godsend. He paints better for it. I suppose you ex- pect me up at your quarters to-night? Well, T won't be there, for I have an en- gagement this evening.” “The moth and the candle,” put in Han- num, with a little laugh. “You sneer at soclety in general and then cultivate it in particular.” “It's only Bannerton “Oh, o Cousin Edith,” explained Edith,” - repeated Hannum Well, you can’t court more than girl at a time yet. You are not far enough along in the society game.” “If any one but you had said -that, John,” answered Hugh, flushing a trifle, “I would call him down with a bump. You know that Edith and I—" “There, my choleric young friend, don't t in on that again. You keep on ching what you don't practice, and you will continue to be consistent in the ways of the world. We will have an even- ing up in the studio as soon as Laurie recovers, and then I shall make you apol- ogize to me. Good-night.” s Hannum turned at the corner and went down the street Bannerton stood and watched him for a moment. “A queer fellow,” he muttered, “but & loyal friend, and true blue at heart. I wonder why he is always arguing that he believes the very things he does mot. I know he feels as I do about the methods of Bidwell and his kind. Still, after all, he is one of those single-gear men; the law, the whole law, and nothing but the law. I must contrive some time to have him and Edith meet. She would have no end of fun with him, and do him good be- sides.” He laughed softly to himself as he walked to his lodgings. It would be such an excellent way of showing this man, prematurely dried and shriveled by the law, that all soclety girls were not the inane creatures he judged them to be. In his deductions concerning the new work and motives of Bidwell, Bannerton was already on the right track, although had little comprehensivn of ‘the mag- nitude of the manipulator's new scheme or the full strength of the forces he had resolved to marshal for what he thought would be his final and decisive victory. Restless and ambitious, feeling perhaps the first touch of waning forces within hjmself, Bidwell had resolved to stake all on one more great battle, in which, for the first time, he proposed to order into active service what had always heretofore been his reserves. For the first- time in his career, too, he made no plans for a retreat in case of repulse. In the judgment of a man who told much in a fearless manner it was fiot to tell the whole truth regarding the men and manners of a bygone time. To- day there is as much to tell as there was of the time of King George, and pretty much the same material it is, with the exception of séme changes in the fashions. Men are much the same, and much the same does position shield them from be- ing called to account for sins of omission and commission. Sixty-one of Lord Mo- hun's peers found him not guilty, as Thackeray has indelibly impressed upon us; and right before us now are men per- petrating offenses for which they pay no penalty beyond the scattering condemna- tion of a few who shoot high, taking great care not to aim at any individual mark. As it was when Mohun walked away from his judges free to resume his old wicked life, so now do the men who offend against the public conscfence strut in the open after each fresh offense. If the people of those times failed to wise id Baunerton firmly, “some- " identify the villainous lords, dukes and princes who moved among them in their lawless. way, much less Is it to be ex- pected that the busy men of to-day will pick out their counterparts in this genera- tion. Is it any wonder that few saw be- hind the pudgy Bidwell's smiling face an areh-conspirator, or realized the extent of his depredations? A plump little man, sedately riding to the office of a street rallway company, of which he is the resi- dent president, is not a spectacle calcu- lated to arouse suspicion, even if he be glven to the idosyncrasy of wearing a silk hat with a business suit. But from the moment that Henry Bidwell first broached the subject of a new franchise to Ledlow, the banker, he had been as busy as any plotter against the peace and security of a kingdom ever was. Tt was a masterly plan that Bidwell un- folded to the banker. INot only did he have a genius for conceiving, but he was also gifted with the ability to present these plans in the most alluring and con- vincing manner, cleverly veiling the sor- did motives behind them and assuming high ground made tenadle only by the bold ‘effrontery of assuming them. One by one the scruples of the cautious banker were swept aside until, dazzled by the magnificence of the scheme and its promise of success, he stood all but com- mitted to it. “It will bring to the good people of this city a cessation of the strife that has ex- isted so long,” Bidwell had cried, enthusi- astically, at the close of their long talk. “There may be some opposition at first, but it will cease within a month after the passage of the ordinance. - We have done much for the city, you and I, but by firm-~ ly establishing a rate of rare, and remov- ing a source of much harmful agitation, we will win the gratitude of all our best citizend.” It was soothing to Ledlow to hear Bid- well talk In this way, and perhaps Bid- well really believed what he sald; we have but recently ourselves, with a Bible in one pocket and wooden nutmegs in an- other,been killing little brown people in a far-off clime in the name of Liberty. The conditions as they appeared to the general public, and even to those who thought themselves on the inside of city and political affairs, were such that the last thing to be expected was that the electric lighting company, which now con- trolled every line in the city, would seek to secure an extension of its franchise, or grants of new ones. Less than two years previous to this time the city had been carried by the Democrats, whose ticket was headed by a man loud in threats against the company—Bidwell, in particular, and the officers of the cor- poration in general. This man, David Thorn, had seized the opportunity to gain the nomination when the popular mind was at a white heat of indignation against both the company and Bidwell. It was ir vain that the press paraded his pri- vate and professional character in no en- viable light. He promised to avenge the people by bringing Bidwell and the un- popular company to book. He was elected by an overwhelming ma- jority. The result was a shock to what is sometimes designated as the conserva- tive element, but it was not long before the public realized that it had been duped. No sooner was Thorn in the Mayor's chair than he entered into secret nego- tiations with Bidwell, ani in less than a year after his election he sent to the Common Council, with his recommenda- tion, an ordinance that had been drawn by Bidwell and his assoelates, and which Thorn had pledged to have passed through the municipal body. It conceded, on the part of the company, a reduction in fares during certain hours of the morning and evening by means of a com- mutation ticket, and the payment of $50,- 000 a year into the public treasury, in re- turn for which the franchises of the com- pany were extended fifteen years, new franchises were granted, and the com- pany was thus given immunity from all competition in the future. Both Thorn and Bidwell were unpre- pared for the storm of popular indigna- tion that greeted this proposed legisla- tion. The press of the city thundered against it, meetings were held at which spcakers representative of every class denounced the ordinance, the Mayor, and the company, and both Bidwell and Thorn were only too glad to make peace by the withdrawal of the obnoxious measure.. Bidwell, who at that time had an eye on @ seat in the United States Senate—and whose unsuccessful campaign furnishes a thrilling story in itself—cun- ningly shifted the burden to the shoul- ders of the Mayor, who was left with no other resource than to explain that he had acted for what he deemed for the best advantage of the city, but bowed now to the will of the people. With these facts In mind, it is little wonder that Banker Ledlow was startled when Bid- well first proposed to him to obtain an ordinance even more sweeping in its character than the one that had been shelved by the protests of an indignant people. To advanne again to the attack after such a repulse required courage of no mean order, and a contempt for the public which rose almost to the sublime. Both of thege Bidwell possessed, and coupled with them was a genius for in- trigue, resources that were the accumu- lation af years spent in forming an un- holy alllance between business and pol- itles and a laxity of conscience that made him hesitate at nothing when once in battle for the corporation that had grown to own him, body and soul. CHAPTER V. A BANQUET ON OLYMPUS. The engagement to which Bannerton referred was a dinner party at the home of Mrs. Warrington, and he had received . speclal message from her to surely be present, The Warrington house was one of the’most imposing mansions on Van- ecsa avenue, the fashionable street oY the city. It was a great, square house of gtone and brick, and little attempt had been made in the way of exterior orna- mentation. It was known in this Western city as “an old mansion,” and while it differed in outward appearance from the other fine residences, it was even more ] One of the Most Attractive Historical Romance divergent in the Interlor furnishings and in the atmosphere that pervaded it. The ceilings were almost twice the height of those allowed by the architects of to-day; on the walls were paintings culled’.from European galleries a decade ago and in niches on either side of the main doorway ‘were marble statues, the like of which |could not be found anywhere else inthe city. The furniture, ‘too, was of what might be called an earlier period, being of mahogany, with haircloth upholster- \Ing, while rugs and rich tapestry com- ‘pleted the setting. Carefully selected and well balanced between the classics and the moderns, the library was such as might have graced the house of an Eng- lish gentleman of culture some fifty years ago. The spaciousness of the dining-room suggested elaborate entertainments after the old English manner. It was here, too, that bluff Captain Warrington, an English gentleman, hale and hearty at 55, had drunk his last toast to his young wife the night before he was found -dead in his bed. Bannerton came early and was warmly greeted by his friend and patron. “It is a little dinner party given by Mr. Bidwell,” she explained. ‘He added you at my suggestion. I wanted you here for reasons of my own and it can do you no harm. You know I am curious, and with you here I shall know all that takes place,” she added, with a smile. “I do not quite understand, Aunt Kate,” N said Hugh, holding her soft hands and looking into the face that he loved so well. ““You' have forced me im where, perhaps, I am not wanted. Besides, you know my feelings toward Bidwell. I can- not overcome them, although perhaps it is.more a dislike of the methods than of the man. He is back. here for some mis- chief. . What it is I cannot fathom as yet.” ‘“That is one of the reasons why I have orranged to have you present to-night,” replied Mrs. Warrington. “I think you can trust to my judgment. He has been strangely reticent with me and I am as anxious as you to know his new plans.” “But how comes he to be giving a din- ner party.in your house? Does it look well, Aunt Kate?” 2 “What an excellent chaperon you would make, my dear boy. . Mr. Bidwell's house ie closed and it will be some days before it Is opened. In fact, Edith is to remain with me, and he will live alone, as he expects to have considerable business to transact. The affair to-night is to be strictly private and I myself suggested that he use my home instead of having it at the club.” . *Ah, so my missing knight has returned at last,”” cried Miss Edith, tripping into the room. ‘“Where have you been, sir? Come, an accounting.” She wore a simple gown of white mus- lin, a bunch of violets in her corsage and her brown hair was tied back in a Gre- clan knot. Hugh thought he had never before seen her half so charming; the ~delicate tan on her cheeks, the bright- ness of her eyes and the dainty freshness of her whole appearance brought back to his mind a young doe he had once seen springing from a bed of moss to gaze open-eyed at him an Instant, as his canoe ish.” s That Has Ever glided along the shores of a northern lake. “Just listen to her,” sald Hugh, ad- dressing Mrs. Warrington. ‘“Was there ever .more impugdent assumption? It is you, faithless one, who should give an accounting!” he cried, turning to the girl and lookirg down on her with a smile. “You rpsh away into- the countryiwith- out a moment’s warning, spend. three weeks at a summer resort and senfl never a ling to your faithful slave, left to toll in the-dust of. the city:. “I was very' busyy with a roguish twinkle “I do not doubt it,” retursied Hugh. “And how many poor young jmen have you left behind with aching hearts?” “With aching: backs, rather,” answered the girl, gayly. “Oh, Hugh, I had the funniest collection of oarsmen you ever saw. A little bit of a fellow from the Bast, who splashed and fretted about and whose father was so rich that the poor_boy didn’t know what to do; a sad young man, who quoted Byron and cast the most languishing glances, and.a nice, romantic old gentleman, who rowed very nicely as long as he lasted, and sang, ‘Row the boat lightly, love, over the sea,’ through his nose. But my prize was a portly gentleman, the most dignified crea- ture I ever met. He was handsome,. too, and he would row all day at just the right stroke for casting, looking at me answered Edith, in her eyes. AOVENTURE OF ANIGHT” HYaH BANNERTn, [T DR. T IIELDORFS poutingly witn great orown eyes, never saying a word. Whenever I asked him if he was tired, he would answer, ‘Oh, no,’ and never move a musecle of his face. We seemed to understand each other, as they say in novels; all 1 had to do was to go down and look at the boat, and he would appear and take his seat, pick up the oars and away we would go. He left three days before I did, and when he came to bid me good-by he drawled: ‘Miss Crosby, I wish fo thank you for the pleasure and benefit your society has afforded me. I came here to reduce my weight." Before I could reply he bowed in ' a stately manner and departed. Oh, I would like to own him!" “Well, T guess you did,” put in Hugh. “But what became of the others?” “Oh, I took little Splasher back. By the way, he was the innocent cause of the only adventure I had during my whole stay at the lake. We went down and across thé lake with the wind and then up came a storm. My! how the wind di@ blow, Hugh—worse than when we ‘were out on the Muskanong in the squall. Poor little Splasher was unable to handle the boat, although I give him credit for being a plucky little fellow. We were soon driven up on the shore and were pounding about on the rocks at a great rate, when along came a gentleman. Hé walked into the water, took hold of the boat and with & strength that was aston- ishing dragged it up high and dry. Then he helped me out, and remarked as he did so: ‘Never make the mistake, miss, of matching a feather-weight oarsman against a heavy-weight boat. The boat will always win when it comes to a fin- He turned the boat over and emp- _— Been Published tled the water out, and you should have seen him do it, Hugh. He was a regular Ajax.” Edith paused and was lost contemplat- ing the picture that came to her mind. ““Well, what happened next?” asked the young man somewhat impatiently. “Did this good gilant seize you and swim back to the hotel with you safe and dry on his back?” “He wasn’t so big,” flashed the girl, tossing back her head. “He was only strong and—and—brave. He righted the boat and then motioned poor little Splasher to take a seat in the bow. But my little oarsman took a look at the waves and said he preferred to wait and g0 back on the steamer. Then the stranger turned and asked me If.§ was afraid, too.” “And you?” broke in Hugh: “I just looked at him an Instant, and then stepped into the boat and sat down in the stern. ‘In the bow,’ he said, just as if I did not amount to & row of pins. ‘The boat will trim better. You will get & bit wet, but that won't hurt you.' Then he shoved off, poor little Splasher fuss- ing around the beach like a hen with a broed of ducklings, and shouting in his piping voice, which could hardly be heard for the roar of the wind, that we should both be drowned.” ““And I think Splasher, as you will call him, was the better-man of the two,” ob- served Mrs. Warrington, who, seated at the window, had listened to the whole recital without comment. “He had finer attributes than mere strength—judgment aud discretion.” “The trip back in the teeth of the gale was grand,” continued Edith, her cheeks glowing with the recoliection. he wind roared and the waves dashed against the boat, but my man fairly lifted it along over the wives and through the white- caps. I could see the great muscles of his back rise and fall, and his arms seemed made of steel. Oh, it was fine, and I was sorry when we were across. I cculd have let him go on and row that way all day.” “I believe you,” said Hugh, looking at the girl with a curious gleam In his eyes, “and I do not doubt he would have done so had you asked him.” To him she was quite irresistible, and he thought all men under the speil. “Did you talk with him after you were back?” asked Mrs. Warrington quietly. “He wouldn't talk, said Edith. “T thanked him and complimented him on his rowing, but he interrupted me gruffly with the remark that he ought to row well, as he had given the best years of his life to rowing when he should have been wtudying. Then he turned and walked off, never so much as looking back once.” “That is a temark I have heard a friend of mine make a good many times,” mut- tered Bannerton. “Did you learn his name?” he asked suddenly. “The man at the dock said he thought his name was Jack Hammond. Oh, Hugh, I believe you know him! You must pro ise to bring him here and introduce him to me.” Bannerton had started at mention of the name. “I know no man by the mame of Ham- mond,” he said, “but from the deScription of the man and his manners, he may prove to be a friend of mine. “If he is, proemise me that you will—" cried Edith, her eyes sparkling. ‘Make no rash promises, Hugh,” inter- fected Mrs. Warrington, rising from her chair. Bannerton looked at the girl steadily and her eyelids drooped, just for an in- stant, as the color come to her face. “I promise you, Edith,” he sald. “I hear tne telephone ringing, Miss Ecith. She turned and, light-footed as a fawn, ran from the room. “Hugh,” sald Mrs. Warrington, “let me tell you something. I first saw Captain Warrington when he felled with one blow & great, hulking fellow who had insulted me. That instant, even before he turned 80 that I could see his face, I knew that he was the man I loved.” “Aunt Warrington,” replied Bannerton, soft and low, and with a smile on his face, “I am glad I promised.” The announcement of Bidwell's arrival was followed almost immediately by his entrance into the room. He greeted Mrs. Warrington and shook hands warmly with Bannerton. “I am pleased to find you here, Banner- ton,” he said. “Mrs. Warrington told me she had une guest whom she desired to invite, and I might have surmised who it would be.” Bannerton bowed, somewhat stiffly, as hz2 was sometime$ quick to take umbrage. When Mrs. Warrington had excused heg- self for a moment, he replied: “It was a complete surprise to me to find myself a guest at a state dinner. I feel that I am intruding, and with your permission I will extend my regrets to Mrs. Warrington. I really have important business to which I should have attended this evening.” “By no means,” cried Bidwell. “I am 1oore than pleased to have you here, al- though it is In no sense a state dinner. I have brought together a number of gentlemen to whom I wish to make an announcement concerning a matter in wkich they are all particularly interest- ed, inasmuch as upon them wtll devolve fu a great measure the keeping up of the city’s reputation. You do some corre- spondence for the outside papers, do you not?” “When there is anything big,” assented Bannerton. “So I thought,” continued Bidwell, “but the fact entirely escaped my mind, or I should have invited you in the first place. It is, I might say, almost essential that you should be present this evening. I owe you an apology for not having you om my lst, but I am, as you know, a busy man, and yoy must pardon me for the oversight.” “But I still feel-” began the young man. “Not another word, my dear boy,” In- terrupted Bidwell, placing his hand on Bannerton’s shoulder famillarly, *“You are here, and I want you here. That is enough. You will no doubt be surprised when you see the somewhat cosmopolitan character of the gathering, but you will understand it clearly enough when I ex- plain my object. Is everything running smoothly on your board? You must let me know if anything should come up. There is no telling when politics will en- ter into a commission of that kind, and there are men always on the lookout for positions such as you hold,” he added sig- nificantly. “Thank you,” said Bannerman; “I ap- preciate your kindness, and realize how essential your help might be in certain contingencies. But at present things are rupning smoothly. “Ah,” exclalmed Ridwell, glancing out of the window, and catching sight of two men who were coming up the lighted there come the first palr, and strangely matched they are—Ledlow and Himmell. One can do enough listening for two, and the other can talk for a dozen.” The guests came rapidly now, and when they were gathered in the great drawing- room, Mrs. Warrington and Edith recelv- ing, Bannerton was Indeed amazed. Re- fore the dinner begins it might be well to look them over and take stock, as it wero —to see them through the eyes of Bannerton, who, moving about hers and there, took up each in his tyrn. He sdw at a glance there wers three great forces represented—the busi- ness world, the politicians and the news- papers. In the first category came August Himmell, Banker Ledlow and Herman Sprogel. Himmell belonged to that class known as the “tired business men”—men ‘who have amassed a fortune in some le- gitimate branch of Industry, and who no longer have time to conduct its manage- -l!- e cried “Alice of Old Vincennes” Begins on October 19.