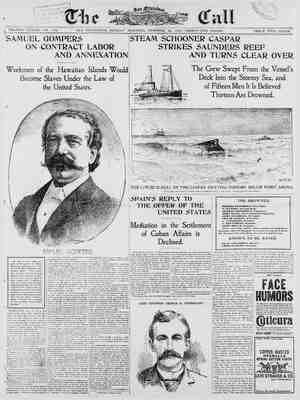

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, October 24, 1897, Page 23

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

, HE giants of the pen are dead. The great books have all been written, and the | world does not hold a great man who is really & great | writer. Literature has fail- | en upon evil times and is now in the hands of the manikins. The books that titudes from the press have not st men behind them. There are d writers by the score, there are * plenty, writers with streaks of | there are sweet singers of minor slists of extraordinary delicacy | of Words, scholars who pro- | rrenged histories and scientific But the no supreme Wh the recent book that one can read over 2 Where s tw historian who can p ing pictures le? Where is the ist who can | like Dumas or Scott? Where is the | » can make his pages gleam like | er who can sound Byrou or Tenny- no force. Itlacks t wrought in any blows and show- flights but low; | wara the | ototype in writers are photog- cenes that few care © heart; there i3 ous do not ema- ch them. dom read; the | holders and railroad | emptupon the | The mer in great thelr ener- , in changing the eartn rather what others have won among the are the writers and eople without any ag- ion in life, men of in- es and scholastics ire has become fem- | or for them. f the skald in eep of the Homeric ttle and gnifi- & sensation, becomes a | ks about it, skims itand | re is the s our heart of m is in them gleam manity. seemed 10 se; through them But torces of nature; they are partof the expres- sion of thoserforces through the brain and the 0. Tney express thoughts will live while humanity continues to exist. Through them sweep the storms of life, and its peace and light. Whatever | the changes inthe languagesof men will b2 found means for their interpretation. For they tell us the tale of the raal ife of hu- | | that | there There have been writers ot whom 1t may be | said with truth, as has been said by a gre critic concerning one, that nature herself | the pen aud utter herself | there are no such being made now; our writers ere not telling | books | | poeti | charged with the beauty and the vitality of the universe, with the power of the spirit of man, so that the least fragment of one of their statues makes all modern works seem ugly &nd contemptible, and the least strain of their music seems like notes from another spbere than ours. One resson of this condition is that books are written now with the fear of the crities before men’s eyes. cause some may aisapprove or condemn. Men write for a living or for fame, aad not because they have some great and noble thing to say. | Literature is small because the men who pro- duce it are not great. fountain. books have been great men. 1n a full sense and have understood what life means. Literature nowadays shows a lack ot convictions. lost meaning for many persons, and without a great and insplring view of life and the world, | how can great things b writien? AUTHORS AND TOBACCO. In his work entitled Medecine de 'Esprit,” M. Maurice de Fleury | devotes a chapter, summarized in this week’s | Lancet, to tobacco smoking from the point of view of men of létters. | fanatical uversi and was co deavor to purge the R ‘gie | invariably covers with contempt the characters whom he portrays as smokers, and an entire in his | consists exclusively | against the weed and its worshipers. | Vietor Hugo: | Miserables' was likewise no smoker. dore de Banville once said: Victor Hugo, Peer of France, no one has been kuown to smoke.” chapter lants” Next, a question of such magnitude that the most rigid scientific proof alo 1e could dispose of it. | I nave known great writers who smoked with- | out stint, but tneir inteilects were not ome | whit less acute. If genius be & neurosis then | why seek to cure it? Perfection is such a very { tiresome thing that I very often regret having | broken myself of the tobacco habit. Aad as 1 | know nothinz more about the question I do not dare to enlarge upon it.” DAYS OF JEANNE L’ARC-By Mary twell Catherwood. New York Co tury Company. The story of the Maid of Orleans will always be read with avility by a large number of readers. In these prosaic days one seizes ravenously on facts that have about them the romance oi lezends. Jeanne d’Arc’s iife was romantic enough to suit a 16-year-old girl or Utterance is strained be- | The stream is tike its | The authors of the really great | They have lived and will therefore turnish story-tellers with fine material until the end of the world. Much will depend, of course, on the manner of treatment. We have become more critical of late, and demand that our novelists ac- quaint themselves with historical facts before weaving nistorical romances. Tne story told by Mrs. Catherwood 18 the resultof patient study and travel in France and careful revis- ing of manuscript. The characters are weil drawn, and a ¢ flesh aud blood men and women of the filleeuth century. are describad in a vivid and raalistic manner, and ine Pucelle hers:1f is made to appear a It1s a materialistic age; life has atroduction & la | Ba'zac professed a | n to tobacco in all its forms, quently employed in an In his books he | a soulless Amazon. The au hors style is sim- ple and natural, and the book should greatly add to her reputation as a graceful writer. AN IDYL OF OLD GREECE. London: “‘Treatise on Modern Stimus= of fuiminations | APHROESSA—By George Horion. “The author of ‘Les| APFIROESSA— As Theo- | *In th se In the bonew o | L e delicaiald sxpemieh thet'i vionn Keats' “Endymion” as it does no other poem since that masterpiece appeared. It is c.assic in 1ts chasteness, and the poetical imagery running through the lines shows that its au bued with the Greek spiritand all that the term implies. The ta'e, told in blank verse, is thatof a young shep- In this connection an anec- * * Comely asa s ripling god, More graceful than a slender reed. tended his flocks in le straying about the mountains Aphroessa, who is a Nereid, appears before The youth Then people begin to ask | the story of the life and thought of manas "“e;“ms'fl;‘!31};‘90:;:‘7“‘{:95 n S tane | 2 cbout, end they find that they | tney are. They are dealing with the super- 3 "]“:;l‘"‘k °w-i Kun;i';‘ ;l:Abeeefl e v their nats over a story | ficies of life. The deoths sre unsounded. Can n, 4. think, fwas' va &-the Beneficent | K D eyt 4 ke ffects of a cigarette on a creative imagina- | thO gh « atin Quarter. A poet | any man honest ¢ literaturc of the | SReCtS T 8 IS htiaBcnbe Sostatearis | s pies and becomes the popu- | day satisfies him, thatitis in any real sense | ‘:;’ ‘_e‘ef_;i(g’o;c .mbo‘ci'; humam hr‘mtzu’-l = SR s PG IR R IR SR U e beneficial: 1t changes thought | bere Spiridon by name: \ something | all the strings of the bumsn soul as | 100U than be : e al swimn masters' have done? What mnov-| S | t tells the story of life in all its| Finally, M. £mile Zola: “Ihave no definite | the | grandeur and its suffe ‘e are playing | Opinion an the question. Personally, I gave | who in days long dead years. How can 1t | at writing; we are ma es, not of | up smoking ten or twelve yea rs ago on the ad | Argolis. Wi ew 1 mod| rature has | epics. Everything is ari, we are told; but | vice of my medical attendant, ata time when > v It is organism, but 8 man- | what art! Dead art, without a soul The | I believed myself to bs a ffected w.th heart | him 10 her he loses his heart. There are books of past| Greeks had art, too, in & sense vastly higher | disease. But to supposs thai tobacco exer- | is dist y and natural as the | than ours, but it lived, and still lives; it was | acted by her loveliness and will not lis- an influence on Frencn literature raises | ten 1o his mother's plea that he marry one of the most ancient of Parisian boulevardiers, | The batties | courageous und womanly creature instead of | | T “Aphroessa” isan idyl so dainty in concep- | the damsels of the village. Marigo, the most beautiful of them all, is scorned auda the youth retires to the hills to live alone and feed his heart with thoughts of the Nereid’s beauty. Oae day he hears sweet music in a neighbor- ing deil and hastening there he s:es his en- chanter dancing with other sprites and all unconscious of his presence. Then he remem- bers that by stealing from a Nereid her veil she is comyelled to follow him who holds it. He attempts to take it from her, but the fair sprites vanish. Aphroessa finally reappears | 2nd leads him a long chase through field and forest and tempts bim until he is nearly dead with exhaustion, As she is fleeing from him her vell catches | | in a brier and §; iridon succeeas in capturing | | it. Then the Nereid follows bim dutitully; | but, after a few hours of happiness, she | | charms the poor shepherd to sleep and lsaves | | him forever. When he awakes his grief is so | | reat that he dies and taere is mourning for | | Bim in the hearts of many people. | The madness of an hour had blighted him, Chanzing hislife to worse than ‘weariness. Haviog disposed of Spiridon, the author | | bewails the fact thet the gods and goddesses | have left us and that their temples have been | destroyed by ravegers. | A NEW THING IN FICTION. UP THE MATTERHOK Mariou Maoville Pope, tuzy Company, A queer story has been appearing in the Century during the last few months entitled “*Up the Matterhorn in a Boat.” This yarn is | now offered to the public between neat cloth covers and should not be overlooked by people who like to take their amusement in literary | form. That the story is an American one | gues without saying. Two men resch the | summit of Matterhorn in a boat. How | this is donme the book tells. A typical English Lord is rescued irom a terrible death, | and every chapter is loaded with amusing surprises. The illustrations are excellent. FOR LOVERS OF THE WEIRD. | | | VAN HOFF, OR T+E NEW FAUNT—Alired | IN A BOAT—By | New York: The Cen- | Smythe. New Y American Pub ishers’ | Corporation. Cloth, 81. This is a strange story and one wall worth reading. Van Heff, the new Faust, is a Dutch scientist who has devoied the greater part of | alifetime to finding somerhing that will re- juvenate the blood by scientific ineans. He | %nows thatif this can be accomplished the | destinies of the human race will be entirely revolutionized. He hopes to attain hisends by the materialization of electricity, which, in its turn, is to be converted into a liquid and | then injected intc the system. Van Hoff ulti- mateiy succeeds in his iabors, but only with the aid of the Prince of Darkness. He then marries & young and beautiful woman, and several characters are introduced 10 lend ¢ 10 the story, the keynote of which is tragi Finally the scientist renounces the evil power that helped him and dies a horr thereby enabling two lovers to be united How all this is nccomplished is related by Mr. Smythein & manner peculiarly forceful and interesting. LITERARY OIESWAND NEWS. The well-known scholar, Dr. Edward Dow- den, !s the author of the important volume on “French Literature” which is to appear shortly in Appleton’s Literatures of the World series. The Rev. S. Baring-Gould is said to be en- | zaged on & Welsh story. ers. Heisanovel writer, & historian, a poet, & country squire, & parish clergyman, a popu- lar preacher and, above all, he is the author bie death, | Mr. Baring-Gould is | probably the most versatile of English writ- | of the well-known hymn, ““Onward, Christian Soldiers.” Robert W. Chambers has published no book | of fiction for some time, and his forthcoming volume, “The Mpystery of Choice,” will be looked for with interest by the many readers of this brilliant and imag: ative young Ameri- can author. The App.cions are to publish the book. The publication is justannounced in London of Miss Garrison Brintow’s translation of Pel- lissier’s *'Literary Movement in France Dur- ing the Nineteenth Century,” & book which in the original has been hailed by no less distine guished a critic than M. Brunetiere as not only the “‘picture” but the “history of French literature.”’ Miss Brinton contributes & gens eral introduction and & very full biblicgraphy. ! R. H. Russell announces two books that are bound to attract attention,itfor noother reason | than their novelty. They are *‘The Alphabet” aud “The Aimanac of Twelve Sports,” both by that dariag genius, William Nicholson, whose vortrait of the Queen in “The New Keview” set all England azog and gave Joseph Pennell hours of exquisite aelizht. -The books will be printed in colors, which wiil be laid on the block by the hand of the artist himssif, The Macmillan Company have Just ready Hallam Tennyson’s memoir of his father. It was put on the market on the 6th inst., which was the anniversary of the poct’s death at Aldworth 1n 189 The work is in two octavo volumes of over 600 pages cach, and contains considerable matter, hitherto unpublished, from Tennysou’s own hand. The illustrations are mostly portraits, but there are some face ‘ similes of manuseript and one or two views. A curious old manuscript hes just come to | light 10 Geneva. Itis dated 1760, and is ene | titled “Epistle of the Devil to Monsieur de | Voltaire.” Whether it was ever sent to press does not appear; neither is there any trace of the name of the author, who affects to write s Sataw’s confidential secretary, The “Epis- | tle” contains eightesn pages, and, as may be guessed from the title, is sarcastic and, not | complimentary to the French philosopher, to | whom the enemy of soulssays in the last page, somewhat paradoxically, “Tout diable que jo | suis, j2 le suis moins que toi!’} | Dean Farrar has for a long time run a tilt with the book reviewer. He says: *<omany of the pure:t and grandest works of genius with which the world has ever been enriched bhave been wampied upon by anonymous ar- rogance, and have continued nninjured, their beneficent influence still ‘adding sunlight to daylight by makinz .the happy heppier,” and so many books, radically useless and un- worthy, have been heralded into life by flour- ishes of trumpets and indiscriminate praise— only to die before the year is over—that I, for | one, wili have as little as possible to do with | praising books which are foredoomed to fail- | ure, or ‘sneering at books which, whatever may be their imperfections, fulfill in any measure the aims which the authors have set | betore themselves, and may increase the | know!ledge or hallow the aspirations of those I who reed them.” It Las come, We have seen it. It has conquered us. Mark Twain ritten a new book that will be as great a success with bi< audiences, th here and in England, as anytbing he has written since the day when lie nailed the scalp of the anmmic Sunday-school boy to the door of his Sunday and exiibited him for the execration of the scholarly Thom yer and his ilk. The 1 Marl est is entitled * production Following the Equator,”’ and thereby hangs a tale. The first name by which the book vas to be ed was “‘The Surviving Innocent Abroad.” It was omnted out bowever, that he was not the sole survivor of the w made that famous voyage to Europe in the twenty-eight years ago, and that the restof the dramatis “Innocents Abroad” sull living might object to having their nplied, even by a humoriat. 1 fix all said Mr. Clemens, *“and I will state in a little reface that, although inere are others, I am the only one who has ned 1nnocent.’’ 1t something changed the author’s intention. About two years ago Mr. Clemens disappeared from the American ntinent, going westward on a journey around the world, “Everybody s done his little circumnavigation, and I thought it about time I did ' be said. His plan was to lecture in the princigal cities through sed and collect material for a book ot travel. He hoped to money to pay the enormous debt which his conscience had n him. Some day the story of thatsingle debt will be as famous 1s of the multitudinous ones of Balzac—with this difference, ay have paid his. o, when his fame as & writer was ripest, he became a firm of C. L. Webster & Co. of New York. An unfortu- z of the book market caused an assignment. The indebtedness to intimate friends cf the author, and he became pe:- or $200,000 of the firm’s debts. He would accept no a basis of 100 cents on the dollar. “'I am not a busi- “only a pen-pusber. And when I borrow people’s ¥ ant to return it.” ¢ With this sentimert and with a dogged determination to succeea he ried on his journey. 1t ot known that entire success has yet crowned his efforts, but his roduced a book. ifying that he himself iscontented withit. Recently he at, more than satisfied with it these later days. I wouldn’t trade it for any I have ever written, and I arh notan easy person to please. st my impression of the world at large. I go into no de- er do, for that matter. Details ere not my strong point, unless I pleasuie to go into them seriously. Besides, 1 am under no pply details to the reader. All that I undertake to do s to interest istruct him, that is his fate. He is that much ahesd. g the Equator,” which is being printed by the American Company of Hartford, to be 1ssued in New York by the Doubleday & M cClure Company, will make a large octavo, well illus- trated with original pictures by A. B. Frost, Dan Beard, Peter Newell, B. W. Clinedinst, Frederick Dielman, F. M. Senior and others, together with hali-tones from photographs taken along the route ot travel. Lacn chapter has as a sort of texta maxim drawn from “Pudd’n- head Wiison’s New Calendar.” The frontispiece isa photogravure of Mark Twain seated alone an the deck of a Pacific Mail steamer. Under itis the legend: ‘‘Be good and you will be lonesome.”” The voiume is dedicated to *'my young friend, Harry Rogers.” The first chapter opens as follows: A man may bave no bad habits and have worse.—Pudd’nhead Wilson’s New Cal- The starting point of this lecturing trip around the world was Paris, where we had been living a year or two, We sailed for America and there made certain preparations. This took but little time. Two members of my family elected to go with me. ‘Also a carbun. cie. The dictionary saysa carbuncle is a kind of jewel. Humor s out of place in adictionary. We started westward from New York in midsummer, with Major Pond to manage the platform businessas fer as the Pacific. It-was warm work allthe way and the last fortnight of it was suffocatingly smoky, for in Oregon and Brit- ish Columbia the forest fizes were raging. We had an snaded week of smoke at aboard, where we were oblized to wait a while for our ship. We sailed st and so ended a snail-paced march across the continent. Mark Twain believes in hero.c treatment. He has alway s believed in it; whether for the purpose of curing ills or ridding himself of an unia, teresting person or for the eradication of mild, attractive vices. In these later days he calls the latter “my nineteen injurious habits,” and this is the way he shook them: Lcan quit any of my nineteen injurious habits at any time, and without dis- comiort or inconvenience. 1 think that the Dr. Tanuers snd those others who go orty days without eating do it by resolutely keeping out the desire to eat in the sinning, and that alter a few hours the desire is discouraged and comesno more. Once I tricd my scheme in a large medical way. 1had been confined to my bed several days with lumbago. My case persistently refused to improve. ¥ the doctor s1d to me: medies have no fair chance. Consider what they have to fight besides bago. You smoke extravagantly, don’t you?” “You take coffee immoderately?” ‘*And some tea?” “You eat all kindsof things that are dissatisfied with each other’s com- pany?” et “You drink two hot Scotches regularly every night, I suppose?” ry well, there you see what I have to contend sgainst. We can’t make Jrogress the way the matter stands, You must makearedbction in these things; you must cut down your consum ption of them considerably for some days,” “I can’t, doctor.” . *“Why can’t your” A LATE PICTURE “Ilack the will power. Ican cut them off entirely, but I can’t merely mod- erate them.” He said that that would answer, and said he wou!d come around in tweaty- four hours and begin work again. He wes taken 11l himself and could not com but Idid not need him. Icut off all those things for two aays and nights; in fact, I cut off all kinds of food, too, and ali drinks exgept water, and at the end ot Ihe forty-eight hours the lumbego was discouraged and left me. Iwasa weil man; 5o I gave fervent thanks and immediately took to ihose delicacies again. As the steamer on which he had embarked approached Houolulu the authorrecalled his last visit there, and his pen works in a more serious, descriptive vein, and the scraps of humor dropped are conjured from a memory of the past. In speaking of the leper settlement e just touches ujon the character of Father Damien, while he lingers with more feeling upon the fate of one whom he had known—*'Billy’’ Ragsdaie, leper. And this is part of the third chapter: We all know Father Damien, the French priest who voluntarily forsook the world and went to the leper island of Mofokai to labor amobg its popuiation of sorrowful exiles who wait there, in slow consuming misery, for death to come and release them from their troubles; and we know wat the thing which he knew beforenand would happen did happen; that he became a leper himself and died of that horrible disease. There was still another case of self-sacrifice, it appears. 1 asked after “Biily” Ragsdale, interpreter to the Parliament in my time—a half-wnite. He was a brilijant young fellow and very popular. As an interpreter he would have been hard to mateh anywhere. He used to stand up in the Pariiament and turn the English speeches into.Hawaiian and the Hawailan speeches into English with a readiness and a volubility that were #stonishing. I asked after him, and was toid that h Prosperous CAreer was cut short in a sudden and unexpected way, just as he was about to marry & beau. tiful hali-caste girl. He discovered, by some nearl- invisible sign about bis skin, that the poison of leprosy was in him. The secret was his own, and might be OF MARK TWAIN. kept concealed for years; but he would nut be treacherous to the girl that loved him; bewould not marry her to a doom like his. Aud so he put his affairs in order, and went around to all his friends and bade them good-by, and sailed in the leper ship to Molokai. There he died the loathsome and lingering death that all lepers die. And one great pity of it all is, that these poor sufferers are innocent. The leprosy does not come of sins which they committed, but of sins committed by their ancestors, who escaped the curse of leprosy! On sailing from Honolulu Mark Twain qu otes from Pudd’nhead Wil. son’s New Calendar as follows: *'A dozen direct censures are easier 10 bear than one morganatic compliment.”’ Brief scenes of life on board ship are set down in the author's diary; scenes that to many travelers are dull and uninteresting in the monotony of a long voyage touch him through their very staleness. The crossing of the equator, while robbed of the old-time pranks of a sailor rigged out as Father Neptune, is made to be remembered Ly a little anecdote, suggestive of when Mark Twain vlayed pilot on the Mississ:ppi “'twenty years after.” On September 5 he made this entry in his diary : Closing 1n on the equator this noon. A sailor explained to a young girl that the ship’s specd s poor because we are climbing up the bulge toward the center of the globe, but that when we should once get over, at the equator, and starg down hill we shouid fly. When she asked him the other day what the foreyard was he said it was the front yard, the open a-ea in the frontend of the ship. That man has a good deal of learning stored up and the girl is likely to get it all- A fternoon. Crossed the equator. In the distance 1t looked like a blue rib- bon stretched across the ocean. Several passengers kodak’d it. We had no fool cere monies, no fantastics, no horse-play. All that sort of thing has gone out. According to Mark Twain the Kanaka or South Sea Islanderis rapidly becoming ciyilized; heis now well-aressed, “'sporting a Water bury watch, collars, cuffs, boots and jewelry’’—when away from hom. But a melancholy fate awaits this garb of civilized man on his retura to his native wilds. The cuffs and collars, 1f used at all, are carried off by youngsters, who fasten them round the leg, just below the knee, as ornaments. The Waterbury, broken and dirty, finds its way to the trader, who gives & trifie for i*; or the inside is taken out, the wheels strung on & thread and hung rcund the neck. Knives® axes, calico and handkerchiefs are divided among friends, and there is hardly one of these apiece. The boxes, the keys often lost on the way home, can be bought for 2s. 6d. They are to be seen rotting outside in almost any shore viliage on Tanna. (Ispeak of what Ihave seen.) A returned Kanake has been furiously aLgry with me because I would not buy his trousers, which he declared were just my fit. He sold them afterward to oue of my Aniwan teachers for 9d. worth of tobacco—a pair of trousers that probably cost 8:. or 10s. in Queensland- A coat or a shirt is handy for cold weather. The white handkerchiefs, the ‘‘senet” (perfumery), the umbrella, and perhaps the Lat, are kept. A hat, an umbrells, a belt, a neckerchief. Otherwise stark naked. day the hara-earned “civilization” has melted away to this. Later on the author expresses sympathy for the Kanaka. This is not strance. He, oo, once owned a Waterbury watch. It was in Honoluiu. He never gave it away, however, for a trifle to any trader. He smashea it and blamed the parliamentary clock. The parliamentary clock had a peculiarity which I was not’aware of at the time—a peculiarity which exists in no other clock, and wonld not exist in that one if it had been made by a sane person.. On the half-hour it strikes the suc- ceeding hour, then strikes the hour again at the proper time. Ilay reading and smoking a while; then, when I could hold my eyes open no longer and was sbout to put out the light, the great clock began to boom, and I counted—10. I reached for the Waterbury to see how it was getting along. It was marking 9:30. It seemed rather poor speed for a $3 watch, but I supposed that the climate was aflecting it. I shoved it half an hour ahead and took to my book and waited to see whut would happen. At 10 the great clock struck 10 again. I looked—the Waterbury was msrking 10:30. This was 100 much speed for the money and it troubled me. I pushed the hapds back a hali-hour and waited once moré, 1 naq 10, for I was restless and anxious. India, with her Brahmins, her Hindoos, her Parsees, her funeral pyres and ber Britizh troops, seemed at first 1o appeal to Mark Twain from the extremes of her civilization—the dignity of her ancient culture, and her modern ignorance and superstition. At firstglance India was what he im- agined ber to be; later on he was forced to see her as she was. And the Ganges, that sacred river, rising high up in the Himalayan ice cave of Garhwal, became at length a dirty, pollution-bearing, sewer-stenching, stream. His impressions would have been more interesting, perhaps, if he had waited a vear and witnessed the horrors of the famine and the plague. He wrote the following after he had lost respect for the Ganges and the pyres: In one of those Benares temples we saw & devotee working for salvation in & curious way. He had a huge wad of clay beside him and was making it up into wee gods no bigger than carpet-tacks. He stuck a grain of rice into each— to represent the lingam, I think. He turned them out nimbly, for he had had long practice and had acquired great facility. Every day he made 2000 of these gods, then threw them into the holy Ganges. This act of homage brought him the profound homage ot the pious—also their coppers. He had & sure living here and was earniug a high place in the hereafter, s e R B R R R S e e A N RS We lay off the cremation-ghat half an hour and saw nine corpses burned. I bould not wish tosee any more of it unless I might select the parties. The mourners follow the bier through the town and down to the ghat; then the bier- bearers deliver the body to some low-casie natives—Doms—and the mourners turn about and go back home. I heard no crying and saw no tears; there was no ceremony of parting. Apparently these expressions of grief ana affection are reserved for the privacy of the home. The dead women Came drapzd in red, the men in white. They are laid in the water at the river's edge while the pyre is being pre- pared. * * Meantime the corpse is burning; also several others. It wasa dismal business. The stokers did not sit down in idleness, but moved briskly about, punching up the fires with long poles and now and then adding fuel Sometimes they hoisted the half ot a skeleton into the air, then slammed it down and beat it with the pole, breaking it up so that it woula burn better. They hofsted skulls up in the same way and banged and battered them. The sight was hard to bear; it would have been harder if the mourners had staid to witness it. 1had buta moderate desire to see & cremation, so it wassoon satisfled. For sanitary reasons it would be well if cremation were universal, but this form of ig is revolting. and is not 10 be recommended. The fire used is sacred, of course, for there is money in it. Ordinary fire ig forbidden—there is no money in it. Iwas told that this sacred fire is all fure nishea by one person, and that he has a monopoly ot it and charges a good price forit. The author passed from India to South Africa and the Transvaal where the elaborate machinery of the modern gold mine astonished bu' dia not disconcert him. I had been a gold miner myself in my day, be wrote, “and krew substantially everything that these people knew about it except how to make money at it.”” While there he made these estimates of tha character of the Boer, of the Presidentand of Cecil Rhodes. * * * Thisis the Boer. He isdeeply religious; profoundly ignorant; dull, obstinate, bigoted; uncleanly in his habits; hospitable, honest in his dealings with the whiles, a hard master to his black servant; lazy, agocd shot, & good horseman, addic ed to the chase ; a lover of political independence, a good hu § ng e exe ks He (President Kruger) must have time tomodiiv his shape. The modifica- tion bad begun, in a detailor two, before the raid, and was making some prog- ress. It has made further progress since. There are wise men in the Boer Goy ernment, and that accounts for tne modification; the modification of the Boer mass has probably not begun yet, If the heads of the Boer Government had not been wise men they would have henged Jameson, and ihus turned a very commonplace pirate into a holy martyr But even their wisdcm has its limits, and they will heag Mr. Rhodes if they ever catch him. That will round him and complete him and make nim a saint. . He has always been called by ail titles that symbolizs human grandeur, and he ought to rise to this one, the grandest of all. It will be a dizzy jamp from where he is now, but that is nothing; it will iand him in good company and be & pleas- ant change for him. Ther- is not an opportunity here for critical study or characterization of this book. Whatisattempted is to give the reader some notion through extracts of its contents. That it will have wide reading is clear; that it will be widely enjoyed is not less certain, Mark Twain puts Lis hand ta nothing he does not iiluminate with his wit and adorn with his wisdom, The writer of our youth is here in his perennial charm and vigor. Allina