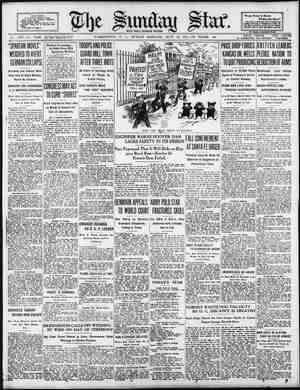

Evening Star Newspaper, July 12, 1931, Page 66

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

(- THE SUNDAY STAR, WASHINGTON, D. C, JULY 12, # immediate profits and engaged in bitter yivalries among themsclves, they haven't for many a day known anything about the tastes, hebits and financial capacities of the rest of the country. They have let their personal rivalries result in too many theaters, in dis- astrous bookings of one play againsi ancther and in a general ignoring of the welfare of the theater as an enduring institution. And be- cause when the rivalry between the two gieat theater chains, th2 Shubeit chain and the Er- langer chain (the former Theatrical Syndicate) first began there was no competition from the “movies,” the motor or the radio, and profits were cacy because the public was, thc powers- that-be never learned how to do business in & competitive woild, and don't know yet. Let us take some of the figures we have quoted, or others we can find, and analyze them, so far &s space permits, to try to dis- cover what they actually signify. Lunt and Fontanne, in “Elizabeth the Queen,” played only in larger citics—a dozcen of -them. They played as part of the Theater Guild's season. In other words, they were supported by subseription audicnces, built up over two p:evious seasons and rcady to start the rush. Prices were not raiced, though pcople were turned away. The play was of sturdy appeal, the acting ample, with the combiried reputation of the actors and the Guild behind the produe- tion to assure the public of a square deal. Even so, the Guild sent ahead of this play not one but two skilled press agents, one to handle the usual publicity, one to establish contacts with schools, colleges, clubs, ete. The play was not turned adrift to take its chances. It was handled with the utmost attention, on rigid business principies, and “sold” to the kind of people most likely to appreciate it. It rep- 1esented a triumph of the organized audience, financial square dealing, the maintenznce of an established trade mark (Theater Guild Play value) and ample, emotionally exciting acting. HE largest receipts of both Miss Barrymore’s tour and that of Walteg Hampden in “The Admirable Crichton” were not taken in thea- ters at all, but in large civic or semi-civic audi- toriums, and the ratio beiween seating capacity and receipts indicates that hundreds and hun- dreds of seats were priced at less than a dollar. This was also true of the “Strange Interlude” tour. The management of thess auditoriums is not an absentee one; it is not in New York. The management is local, and the entertainments in these auditoriums take on a civic character. More than that, they are generally sponsored by one or more civic groups, or brought to the town by a local concert manager who has his own ways of getting support. From the moment the play is booked there is a campaign on in that town to awake inter- est and sell seats. This is all the easier be- cause, being under local management, only those plays are booked for which some local demand is known to exist, and which are of the kind acceptable to that community. The reason why a Shakesperian company succeeded in Salt Lake City last Winter was because the Mormon Church, always ftiendly to the thea- ter, invited it there and rouse the interest. The reason why Walker Whiteside played two enormous performances in Omaha was because the local Drama League booked him and per- sonally saw to it that the tickets were sold. It became a local matter, and he had several hundred advance agents in that city. This last Spring Mis. Piske made a tour, under the management of Tracy Drake, owner of the Blackstone Theater, Chicago, which is now an independent house. In the tour were several weeks of one-night stands, those stand- bys of the old-time theater which used to yield a play a profit for a whole year, or even two years, after its big-town time had been ex- hausted. In many of these towns she played in “movie” houses, because they no longer pos- sess “legitimate” theaters. ‘The results were, to say the least, interesting. Ia Jowa City, Urbana, Ill, and Bloomington, Ind., business was excellent, for the simple rea- son that the performances were guaranteed by the State universities in those respective towns, and were booked there because a number of people wished to see Mrs. Fiske. In certain other Midwestrn towns business was bad be- cause, as Mrs. Piske’s manager put it, a “ninth company” of some second rate show “had just bilked the natives so that they had all joined an anti-theater association for mutual protec- tion.” The excuse given for poor business in certain Michigan towns was that Ethel Barrymore bad been there the week before, and the local pock- etbooks weren't equal to a play & week. In Pennsylvania business was very bad. Here there were no college guarantees, and no ad- vance work by local groups. Both the advance agent and company manager with Mrs. Fiske were wise in the ways of the theater, and they both declared after the tour was over that the greatest opposition they encountered on the road was not the “movies,” but the local theater manager when he belonged to the old school of sublimated janitor for the absentee owners in New York. These men they found quite out of touch with the present-day theater and its problems, without any lists of prospective patrons, any follow-up methods, any initiative in making contacts and carrying out a sales campaign. HE company agent can be in a one-night stand only a day. He has to trust the local house manager to carry out his publicity cam- paign. If all the house manager knows is to sit behind the box office with a cigar in his face, that town might just as well be wiped off the list. It is certainly dead so far as the “legitimate™” drama is concerned. books only the star or play he thinks sell to the community without inj standing, and only as many of thinks his community can afford. fanitor, taking anything that New Y. 1931, Amateur dramatic activities of the community go far to promote an interest im the professional drama. him. He knows his town and his people, and he is there on the job, working all the time. Generally such & man has the backing of Jocal clubs and organizations, and in a sense represents an organized audience. Often he is able to give positive guarantees to a play. It is noteworthy that the Guild, which originally built up its standing by means of an organized audience of subscribers in New York, has made frequent use of the concert impressario for its road tours of the smaller cities, and three years ago, when it sent a repertoire company on the road, booked the entire season through a eon- cert agency. What it amounis 0 is that the predic- tions made by a lot of us years ago, when the Theatrical Syndicate first acquired its chains of houses across the land and pro- ceeded to control them by absentee land- lordism, have been more than fulfilled. Re- ducing the local theater managers to the status of janitors, of course, has killed their initiative and made them incapable of a fight for survival. Shipping into a town any and all plays, with no consideration of the town's financial capacity to absorb them and no consideration of the town’s taste (it being gemerally assumed that the town had no taste), has disgusted millions of former theatergoers. Finally, the rivalry between the Erlanger and Shubert camps, resulting in two thesters in places where one really going to see that play and those players, and if made sufficiently aware of the impending attraction. They certainly don’t want any ‘“original Broadway They have been stung by that know, have heard glowing accounts of. That is only matural and it is nothing new. Jt was always so. Our parents went to see Booth and Jefferson and Modjeska. . But #t wouldn't bave surprised her if she had lived in one of those even in North Carolina (one of the two States which gave her the largest receipts) many plays by local authors about local life. ‘These people know a play when they see it. They are also quick to respond to fine acting and resentful of bad acting—much more re- sentful than is Broadway. They want the theater to be a2 creative adventure to mean a lot I their lives. If it ean't do that they will have none of it. Hence it is perfectly understandable not only why the star actors do the best business on the road—and especially the stars who are old enough to have acquired a wide reputa- tion and matured power—but why today they do the best business in those towns and cities which have either a theater or a civic or other auditorium that is not controlled from New York, but is, instead, managed within the community. In such places book- ings are made with due consideration of the community purse, cheap shows are kept out and hence public confidence is maintained, rival dates are eliminated and the primary consideration of the local taste is not lost sight of. The interest and support of local organizations are enlisted. The people feel it is their theater, not a shop kept by somebody in far-off New York, and they take some pride in it. All of which bolls down to the fact that = / what the theater needs on the road is a sufe ficient number of locally managed, inde- pendently conducted houses at strategic points to take care of the good plays and the es- tablished stars, and to ignore all others. It is useless to expect such houses in all towns. There would not be enough good productions to fill them if they existed. But a hundred such houses across the country, with the larger cities supplying 60 per cent of the booking, could insure highly profitable season tours to .all really “legitimate” attractions, and nobody would talk about the road being dead. And it is coming, perhaps faster than we think. NOTHER thing the poor old theater will have to get over, besides its idea that any old play, tossed any old way on to the stage, is good enough for the hicks, is the idea that there is some magic superiority in its “legitimacy.” The public, especially the younger public, doesn’t draw any hard-and- fast distinctions betwe:zn legitimacy and its opposite. It regards theater-going as a form of entertainment, whether furnished by living actors or their photographs, and it looks for what it thinks will give the most entertain- ment for the money spent. Whatever you and I think of the “movies,” we cannot deny that the people in the smallest town can and do see the very same playe's, the very same productions (minus, maybe, a sym- phony orchestra and a ballet between films) which are visible in the largest cities. The very best acting, the very best screen drama to be witnessed, are available everywhere—at least those of American manufacture are. And they are available for much less money than the spoken drama, much more frequently, and gen- erally under far more satisfactory physical con- ditions. The theater is cleaner and newer, the seats are more comfortable, the ushers are more courteous, and so on. As a result of all this the people of the whole country have developed an instinctive sense of competence to play presentation. I don't say the masses have developed a sense of com- petence in the higher reaches of play writing, for that would not be true. But in the matter of dramatic surface, at least, and in the matter of acting, setting and the projection of vivid personalities, the masses of Americans have been taught by the “movies” to know the good from the bad. Not only have the “movies” long since killed entirely the old-time “ten-twenty- thirty cent” melodramas, like “Nellie, the Beautiful Cloak Model,” which Owen Davis and his school used to write, but the “talkies” have now made it virtually impossible for poor and incompetent second and third companies to survive on the road. As between a cheap road company acting a flimsy comedy with even first-rate players couldn't make a real success on Broadway, and a movie produced by a Clarence Brown, let us say, with vivid personalities to project all the leading roles, who wouldn't choose the “movie?” ‘The more, of course, because he“could probably see it cheaper in a much cleaner and more comfortable theater, and at his own time. In other words, what the “legitimate” the- ater is up against on the road is the stiffest sort of competition—not with a second-rate product, but with a first-rate product—with the very best America has to offer on the screen. It can meet this competition only by giving its own best, not its second best, and most assuredly not its worst—which in the past it has too aften tried to foist upon the provinces. And .it‘can meet this competition intelligently only if it knows what it has to offer that is different from the “movies,” and that knowledge will inevitably lead to a knowledge of what kind of Ppeople to appeal to, and how to appeal to them. If the theater producers were wise, if they even attempted to run their business on busi- ness principles, they would have insisted long ago that all the theaters they control on the road keep a list of regular patrons and know exactly what sort of plays they come to; even now they would make a careful survey of all the companies on tour in the last two or three years, to ascertain receipts, town by town. In those towns which showed a profit with some consistency the local theaters would be eon- sidered, the type of local manager, the nature of local civic support. Still more, perhaps, the survey would extend into the amateur dramatic activities of the town or community to determine how far such activities promote an interest in the professional drama. OR instance, 12 years ago Sam French didn't even bother to send his amateur play catalogues to North Carolina, because interest in the theater in that State was virtually ex- tinct. Today, thanks to the work at the State University, every high school has its dramatic club, the university players tour the State with plays about local life, and Paul Green has arisen. It certainly seems highly likely that there is a connection between all this and the fact that Miss Barrymore drew her second most profitable audience in this State and “Strange Interlude” did large business there. Both “Interlude” and Miss Barrymore drew huge receipts in certain cities of Texas, in Oklahoma City and in Memphis. In all these places there are flourishing Little Theaters which’ have enlisted civic interest, or there are university players, Mrs. Piske was most suc- cessful on the road in university towns where there is much play production. If then a careful survey of the field should show a definite relation between good business and amateur activity the answer is plain—let the professional treater co-operate with the amateurs and build up more such work. There are a hundred, a thousand ways in which it could co-operate. Any manager interested can learn what they are from his fellow manager, Kenneth Macgowan. Further, of course, such a survey, if carefully and intelligently made, would show quite clearly the type of play and players the road wants to see, the type of theater and community in which success is most likely, the kind of people to appeal to for patronage and assistance, and would at least point the way toward a realiza- tion of what it is in the living drama which the “movies” do not supply to large numbers of people, and which accordingly can still sur- vive to the profit of all concerned.