Evening Star Newspaper, July 12, 1931, Page 19

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

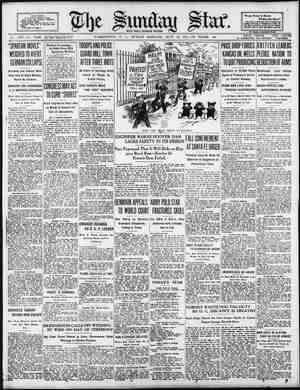

Editorial Page EDITORIAL SECTION he Sundiay Star. Part 2—8 Pages WASHINGTON, D. C, SUNDAY MORNING, JULY 12, 1931. DEBT DETAILS DIFFICULT, Politics Will Not St . Plan With Gibson ¥ BY CONSTANTINE BROWN. 4 FTER a harmful delay of some 17 days the principle of the Hoover plan has been accepted by all interested nations. The acceptance is, of course. full of #ifs” and “whens,” but still Germany been saved, for the time being at t, from disaster. As in many international discussions, there has been a good deal of give and take. No nation can say that it has won & victory over the other. President Hoover had in mind to save Germany from immediate bank- ruptey; he has succeeded. The Prench wanted to safeguard the principle of the continuity of the Ger- man obligations toward the creditor nations and the principle that post- war treaties cannot be revised. They mlso have succeeded. They have the patisfaction of having won the bout with us “on points.” The President wwished that the payments of this year's Bnnuity should be spread over a long riod. He wentloned 25 years. The tate Department indicated that we ould be willing to compromise on 17 ears. In order to save the principle ©f the Hoover plan we accepted a 12- pear period. The future will tell Whether this period is long enough to knable Germany to pay her obliga- glons. We left out of the compromise & number of important details which have to be straightened out by the Sreasury experts. Our jack-of-all- trades, Ambassador Hugh Gibson, will be in London with the experts as an official observer. Matters will be re- ferred to him_ whenever there will be &n important hitch—and there will be many. The technical experts will begin to work on July 17 and are likely to spend a long time in the capital of the British Empire. Optimists say that their labors will be ended within the next three months; pessimists declare that it may take three years. It all depends on the attitude and the interest of the va- tious European governments. Politics Introduced. ‘The truth is, however, that while the President has been trying hard to keep this question of intergovernmental debts and reparations outside the sphere of politics, the European gov- ernments have managed to introduce politics under the cloak of ‘“expert’s ‘work."” The success or failure of the work which is beginning in London depends, to a great extent, on how far the Ger- mans are willing to yield political The financial aspect of the situation, @s far as France is concerned, is really | of minor importance. The French, by | accepting the Hoover plan, have made | 8 financial sacrifice greater than the United States. By the Hoover agree- ment this country is losing this year | some $260,000,000. The French are | losing a little more than $100,000,000. | But, while this sum in the United | Btates can be divided among a nopula- tion of some 125,000,000 inhabitants, the hundred million dollars the French are likely to sacrifice must be eventual- Iy paid by & population of less than 40,000,000 people. The proportion be- tween our sacrifice and the French sacrifice is something like 2:213. Fur- thermore, while this sacrifice will have to be born in America by those indi-‘ viduals who earn at least $4,000 a year, | in France it will have to come out of the pockets of individuals or heads of | families who earn 12,500 francs a year about $500). Consequently in the case that the German reparations are lost | the burden will be greater for the| Fronch than for the American public. he French, bowever, don't scem to Vi much about this potential loss, d if the work of the experts’ commis- >n will be protracted and the French show an adamant spirit the reason will b: found, not in the footling techni- calities of reparations in kind, but in the fact that the Germans are not willing to abandon their freedom of doing what it is best to improve their situation in the world. Busy Months at Hand. During July and August European | BUT GERMANY SAVED ay Down While Ex-| perts Work Out Conclysions of Hoover as U. S. Observer. unchallenged great power on e European continent. If France shows the slightest weakening, the economic interests of the little entente states will draw them toward Germany. If that happens, the days of France's hegemony in Europe will be ended. For this reason France feels com- pelled to prevent any action which might be interpreted by her allies as: “France is becoming powerless now. | France has taken a definite stand against the Austro-German union. She informed her allies confidentially that she will not tolerate that this union.should become an accomplished fact. The matter was referred to the Hague tribunal and is awaiting the decision of that international court. Had the Hoover plan not intervened at the present moment, France might have been able to accept with grace her defeat (assuming that the Hague Court should decide in Germany's favor). But now, since in the eyes of Europe she appears to have yielded to America, it is a matter of great importance for her prestige to have the plan for an Austro-German union abandoned. Before the e Court renders its decision, the French diplomats will do their utmost to obtain from the Ger- man chancellor and his foreign secre- tary a promise that the tariff union will at least be indefinitely postponed, if not abandoned. It will be hard to obtain this from Herr Bruening, but there is no question that he will have |to show a great deal of strength of | character to resist the assaults of the | French cabinet when he meets them in Paris at the end of the month. To accept the Austro-German union means to the French to show weakness. They are in the position of the lion tamer in the cage. The moment the animals, if they are young and wild, see the | slightest sign of weakening, he is lost. |and it is up to the attendants outside | the cage to save him. It is doubtful | whether France wants to be put in | that position. Matter of Minor Import. ‘The matter of France asking Ger- | many to abandon her activities in | favor of the revision of the Versallles | treaty, and especially her dream of re- | covering the Danzig corridor. is of a minor importance today. Germany can | give officially all the assurances France wants on that subject, but she cannot repress national and public sentiment any more than PFrance could prevent her own citizens before the war from | agitating in favor of the recovery of | Alsace-Lorraine. In a case like this| official assurances are worth nothing. | The question of the conversations re- | garding the coming disarmament con- | ference s, of course, of the highest im- | portance, for us more, probably, than ! for the French. The Germans are on solid ground when they demand that the Prench should bring down substantially their present armed strength. The Germans claim that it is a disgrace for the European powers that 12 years after the war, when Germany has fulfilled all her obligations regarding the reduc- tion of her armed forces, France and her allies should be still’ fully armed We, through President Hoover and other representatives of this country, say that the trouble with Europe is! that she spends too much money on arms and armeament, and that it is Jjust this extravagant and unjustifiable expense that is at the bottom of Eu- rope’s economic trouble. The British have joined in the chorus and have been warning continental Europe in the last few weeks that she must seriously | consider disarmament. | Italy, although one of the countries which is spending much on her na- tional defense, would be willing to join the United States and Great Britain and disarm, but she feels that on ac- | count of her geographical position and | on account of her unsolved political dif- ferences with France and Jugoslavia she cannot do so. She is, however, willing to disarm if her neighbors do the same thing. The little entente states, France's satellites, claim that they cannot reduce their armament as prime ministers and foreign ministers | Jong as Russia continues to threaten will be very active. A number of offi- | them. France finally says that evrith clal conversations between the French|a sturdy German population across the end the Germans, the Germans and | Rhine, a population full of hatred for the Italians, the British and the Ger- | France and by 20,000,000 superior to mens and the British and the French | the French population: with the Ital- are scheduled to take place. Secretary | {ans rattling the saber on every occa- Stimson, who arrived in Europe on | son, she cannot possibly consider re- July 7, will see privately all these Euro- | ducing her forces unless she has ample n statesmen and will talk to all of | guarantees from Great Britain and the em and use all the prestige of the | United States that the present peace United States to avert a clash and| treaties will be maintained, and that :umme the general disarmament con- | fer present territory will remain in- erence. tact. Secretary Stimson's task is not an| % gnviable one. He will talk reconcilia- tion, co-operation and the nced of a Possible French Attitude. When the Germans go to Paris to it LR~ neral disarmament to people who | ink about security and see dangers everywhere. He will say “Let's get to- gether and forget all about this re- swered, “What are you going to do for us in case we are in trouble?” The old eonflicting theories between the French and the American point of view are bound to spring up stronger than ever before. We say disarm first and then we can talk security. The French say glive us a full guarantee that we shail not be confronted with another inva- sion of our territories and we are ready to talk disarmament. It will be difficult to reconcile the ¥French point of view to ours. In order to co-operate heartily for Germany's economic reconstructions the French want definite assurances from the Germans _on three specific questions: First. On the question of the tariff union with Austria, Second. On the question of aban- dcning the idea of revising the Ver- sailles treaty, especially in regard to the Danzig corridor. Third. On the question of the com- ing_disarmament conference. The tariff union between Germany Bnd Austria has been worrying France eatly ever since the Germans made fl' clear that they intend putting their plans through in spite of what any | ha; other nation may say. pror :«:?w:ammu.wc t is also an gconomic question. The latest financial developments in Dentral Europe have proved.to France how ly connected were the economic institutions of Central Europe with Germarny. The collapse of the ‘Austrian “Credit Anstalt” caused a run on the German banks. The weakening | the of the Reichsbank in the last two ‘weeks remtgf k\;pon Rumanian and ungarian banks. ,‘i'rhe economic link between Germany and Central Europe is already definite- Iy established and awaits only an offi- cial act to confirm it. PFrance needs, litically, to maintain her hold on umania, Czechoslovakia and Jugo- via. .l"rhe countries which belong to the entente play the French game as long as France remalns | ties of a better understanding between | co-operation, as indjcated by President ciprocal mistrust,” and will be an-| discuss with the French the possibili- the two countries hased on economic Hoover, they are /likely to find the French diffident. /The French ask for nothing better than an economic co- operation but thgt on ti own_terms. They want as proof &f faith on the part of their neighbdrs across the Rhine the gbandonment of all their political ambitions. They want the Germans not to press the disarmament question too, hard next February at Geneva_ and let France play her cards without Germany's interfegence. The Germans will undoubtedly e told that they can pe assisted econoniically and that Frapce might conceivably agree even to a revision of the Young plan payments, if the Reich leaves the he- gemony pf Continental Europe to France. Secrefary Stimson, who has left this country full of hopes that he will bring together! the European nations to agree between themselves before the Geneva BY ANDRE SIEGFRIED, Author of “America Comes of Age.” MERICAN civilization expresses more than any other in the en- tire world the idea of material progress. At the same time. largely due to the war, the United States has become the richest and most influential country. In a word, she has become a world | power, a term which until quite lately we used only for a few countries in Europe. This fact, really new, has re- sulted in some problems, also new, which we did not have before the war. What are to be the political relations of the United States with the rest of the world as a result of this? And what is to be the effect of the American concept on Western civilization and on | human civilization in general?> There are no questions which affect mropt‘\ more directly than these. They touch the private life of each individual. Until very recently the United States manufactured goods. Wheat, meat. cot- has enjoyed a very exceptional economic |ton and oil formed three-quarters of independence. Foreign countries have |the exports. This is essentially the needed her more than she has needed | commerce of a people economically them. If we consider, for example, the | young who are not yet developed indus- exports from 1886 to 1890, we ascertain that 84 per cent of them were raw |outside of their own borders without material and only 16 per cent were :turning them into manufactured ar-| Why So Many New Novels? What Is Urge Behind Production—Are They Written for Money or Fame? BY HUGH WALPOLE, HAVE noticed during these last months a certain agitation in the | Ppress as to Why so many novels are | written today. ~Mr. Harris asks the Daily Pleadc urgently, “Why, | oh, why do novelist. write novels?” and Mr. Gamp replies the very next day, “For money, of course,” and then Mr. Peacock sends a letter saying “I write | only because I can’t help myself,” and | Miss Thrush sends a little letter saying she writes because she wants ever so much to help people ever so little. | trially, and who sell natural products | the val, stepping out at the other, meeting in February, will probably have a pretty hard time with French. It ¥s opinion of our diplomats the that the Franco-Italian naval ques- tion 'must be settled before we can hope, for success at Geneva. Had Secref St n arrived before Hoover proposal he would ve French in a val trouble is no longer very serious; it's just & matter of inteypretation and good will. The French were on the it of press as the dirtatorial attitude of the Anglo-Saxon countries. The French politicians and the press have talked a good deal in the last two weeks about heavy sacrifices France has been forced to make to save Mr. Hoover's second as President and the $2,500,000,000 the American bankers T ic opinion consequently is op- posed to any further copcessions. If the concessions required from France are of & nature which might appear to interfere with her plans for national defense, Mr. Stimson will cult to obtain anything from Vany French government. The tone of the the | French press, which is aaf excellent ve | than it was 25 years ago. There are Then Mr. Priestley irritates the Ameri- | cans, Mr. Dreiser smacks Mr. Sinclair | Lewis’ face in public and the critics ex- | claim with one voice, “See what this novel writing leads to!” | Now, let me start off by saying that, s0 far as the critics go, they have all | my sympathy. Of course I like critics— | what novelist in his senses would ven- | ture to say that he did not? like the critics. I think they rottenest of all possible jobs. pecially with regard to the novel. General Merit Higher Now. Twenty-five years ago I reviewed for four years all the new fiction that came into the Standard office. At least, the place where it really came was my small and not very airy room in Glebe place, Chelsea, and I can still, if I am not very well, smell the fresh, sticky | odor and see the bright, commonplace | backs of all those new novels stepping in at one door and, after a decent inter- | have the | And es- The stream, except for two months | in the year, was continuous. It was a nightmare, and had I not ceased I should have gone mad. How Mr. Gould, Mr. Hartley and other brave lads have saved their sanity all these years.I can- not imagine. For it is much worse now many, many more new novels and the general level of merit is much higher now . The room at top is as s filled as ever it was, but below the top floor—just below it—there are a great many competitors, Why Be Angry at Authors? ‘This makes the work of the critic all the harder. He can abuse, dismiss or easily praise the work of Mr. Wells or But Ido| k World Role for America Noted French Economist Analyzes United States’ New Position in International Trade and Politics. —Drawn for The Sunday Star by J. Scott Williams. ticles. Every one knows that it is easier to sell raw products than manu- factured goods. In fact, Europe came to America looking for products of the | As a result the impres- | American soil. sion grew that Europe needed the United States—and this was far from being false—but that the United States did —Drawn for The Sunday Star by Rodney de Sarro. “WHY, OH, WHY DO NOVELISTS WRITE NOVELS?” novels that drive the critic into & {renzy. But in the first place, ought he to be in a frenzy—ought anybody to be in a frenzy—about the of novels? After all, as Mr. marked somewhere the other day, there is nothing quieter than a new book. It does not go about the streets barking like a dog. No one is compelled to read it. It is perfectly easy for any one, if he or she pleases, to avold all con- tact with new literature. 1f they neg- lect, four or five journals and never look at a bookshop window the deed is done. I have never understood why anybody should be angry with an author! Why, find it - | broken authors are insulted, abused, libeled, smacked in the face in a fashion that would, were it applied to a doctor, a lawyer or a haberdasher, lead to an instant action for libell Each Has Urge to Write. ‘There is one critic on a London news- paper who apparently is sick every morning because there are so many novelists in the world! But why does he torture himself? Novelists are of very. little importance in the general af- fairs of the world. ey are not, like pugilists, flm stars . Bernard Mr. Galsworthy. He can pat on the back or laughingly reject the obvious commercial novel, but between these is a great multitude of clever, en- terprising novelists who write well, avold sentiment, have ideas. These the barometer, is already unfavorable. The feeling in France is that Italy must yleld, that “it is high time for the to stop paying for the is in this atmosphere that the American Secretary of State will have to carry on his negotiations. Shaw, always with us. They never are mentioned unless they are divorced or some one gives them one in eye. I cannot understand why this gentle- man should make , every morn- ing, so miserable. Which brings me back to my original ‘Why do_novelists write nove rrespond cause of a desire for fame, because of & desire for money, because of a desire to do people good, because of a desire to do people harm, because they can't help it and because they have nothing better to do. Discards Fame as Object. These seem to be the reasons, and I will say at once that I think that all of ttese have something to do with it, but that only one of them has really any- thing to do with it. For fame? That is certainly a good reason. Why should man not desire to be famous? There seems to be a gen- eral shyness about admittirfig such & thing. “Oh, no,” says Mr. Blossom, the well known novelist. “Fame is the last thing that I have in mind. If one or two people happen to like my books” Nonsensel ~ Of course he loves [ COMMODITY PRICE DECLINE INCREASES GERMAN DEBT Hoover ‘Action Held Caused by Boost in Obligations Based on Value of Products Since Young Plan. BY MARK SULLIVAN. HAT happened preceding Pres- ident Hoover's proposal for postponement of _intergove erzmental debts has been fragmentarily told here and there. ‘The telling, so far, has been from the dramatic standpoint, and dra- matic it was. The full story, however, includes—indeed, starts from—a cause that is not dramatic, but very impor- tant to the world and likely to be heard in, even in relatively placid ica. In 1929 Owen D. Young and others fixed $9,249,000,000 (present capital value) as the amount of reparations | Germany must pay. The amount at the time was regarded as reasonable. | It was fixed In the spirit of reason, chiefly by neutrals. The common judg- ment was that Germany could comfort- ably pay it and the interest on it in the 59 years she was given to pay the annual installments. Owes More Today. Germany was required to pay $9,249,- 000,000. Germany up to date has actu- ally paid $700,000,000, as called for by the Young plan. But Germany today owes more than when she began—much *| more. This paradoxical statement of the fundamental difficulty of Germany (and to & less degree of ourselves and of the world) is here adopted deliberately. ‘There need be no apology. The state- ment is true. It will be indorsed by any economiet or banker. ‘To understand the truth behind the paradoz it is only necessary to remem- ber the changed value of the dollar (or of the reichsmark or any other gold unit of currency). It can be put in a way that any one can understand and which will be particularly clear to farmers. In June, 1929, when $9,249,000.000 was fixed as what Germany must pay, a bushel of wheat was worth, roughly $1. (I do not attempt to be exact.) But today a bushel of wheat is worth, Toughly—let us say for the purpose of simplicity, half a dollar. Consequently, ‘when ‘Germany's debt was fixed in 1929, | parties believe in not paying repara- ltiom. ‘The Fascists' program is to stop paying the reparations but to continue paying all other debts. The Com- munists, of course, would pay no debts, public or private. The strength shown by these two groups in_the election of 1929 scared German business men, bankers and other conservatives. These, feeling their money was unsafe in Germany, began quietly to send it out of the country, to Switzerland, to Holland, to the United States. This early “flight of the mark” was arrested by realization that after all neither the Communists nor the Pas- cists had actually triumphed in the election; that the German governtent was in conservative hands and that the German people under normal condi- tions are an orderly and conservative nation. “Creditanstalt” in Crisis. Then, about six months ago, in neighboring Austria. a great bank came to grief, the “Creditanstalt,” which did about two-thirds of all the banking business in Austria. The embarrass- ment of the “Creditanstalt” put a strain cn the German banks, increased the feeling of uneasiness in Germany and started a new flight of capital to | America and elsewhere. This flight of | German capital to America was one of | the reasons for piling up all the gold {upon us; instead of helping us it has, |so_far, increased our economic diffi- | culties. | Meantime the @epression in Germany grew worse. The German government, in order to meet reparations payments, | was obliged to decree new and heavier taxes. The decree. issued on June 6, | was accompanied by 2 manifesto. The manifesto, addressed partly to the Ger- |man people and partly to the werid, had the effect of calling spectac-lar |attention to Germany's financial and social difficulties. | The next day. June 7, by an unfor- tunate juxtaposition, was the date fixed for a visit of the heads of the German government to the heads of the British governmen:. The world assumed that the debt was 9.249,000,000 bushels of |the Germans were going to England to |declare their inability to pay repara- wheat. Today, even after she has paid her installments regularly for nearly two years, her debt is 18,498,000,000 bushels of wheat. not need Europe. Thus_ there devel- oped a feeling that the United States enjoyed a sort of continental autonomy; | that is to say, a real impunity. No| matter what tariff should be imposed, | no reprisal was considered possible. To punish America, Europe would not have deprived itself of cotton, oil or wheat | Twice as Much Copper. To put it in terms of another com- modity, copper, Germany’s debt in 1929 2mounted to 57,000,000,000 pounds of copper at the then price of 16 cents a pound. Today Germany's original debt amounts to 115,000,000,000 pounds of topp!l",dlt the present price of 8 cents a pound. For the purpose of simplicity I have stated Germany’s case worse than it really is. Not all commodities have ¢ down so far as wheat-and copper. | ut all have gone down. The average. rn;m t:m United States. And this men- z*e:‘!:d very roughly, is about 36 per tal attitude of isolation and impunity is | | so strongly ingrained in the A'l“uer’fé&n‘ To explain a little further, returning ’uonsv Actually this was not true. But the incident increased the feeling of |alarm about Germany. Two Roads Seen. It was felt. both outside Germany |and within, that the country was des- | tined to take one or two radical roa |either—as 1t has been expressed by |German writer—"the Fascist road, | which means reparations debt repudia- | tion, or the route to thorough Com- | munism, leading down the red Russian |Toad to complete collapse of the Ger- | man social order.” In this apprehension about the politi= cal future in Germany, the flight of capital became not merely a flight, but a headiong rush. The Germans sent their money to Switzerland, the United States or eisewhere. Outsiders who had loaned money to German industrial in- people that it persists even at this mo- ment. when circumstances have changed considerably. For independence is fast being re- placed today by interdependence. For- |eign trade. a faithful witness, demon- strates this change very clearly. Im-| portations of raw materials have grown in volume from year to year. In 1927 they were 50.4 per cent, as against 38.4 fg;ocent during the period from 1886 to | ‘The United States depends to a very | | formidable extent today on-foreign im- portations of silk. rubber, paper, coffee (Continued on Fourth Page.) | to be famous. He would be miserable, | he would die of chagrin, if no one ex- | cept his wife and his tailor spelled his | name right! ¢ | And yet I do not think this is a main | motive. Fame may be pleasant, but it |is a greedy devil. The more you have, the more vou want. You are undoubt- edly quieter and more happy without | any thought of it. There is no author | alive, I suppose, who is not comforted | | sometimes by the thought that one day after he is gone some one, somewhere, will pick up a shabby copy of an old | to wheat as an easily understood illus- tration, all the dollars in the world have grown bigger. What was a one- bushel dollar is now a two-bushel dol- lar, Dollars are bigger and harder to get. | 'This bears hard on all who are obliged to produce a given number of dollars. Germany is not the only debtor who suffers. Every private debtor in the world suffers. The classic illustra- tion is a farmer who gave a mortgage on his farm at a time when a bushel of wheat would pay off a dollar on the mortgage—and finds the mortgage come due (or the interest on it) at & time when it takes two bushels of wheat to pay & dollar of the mortgage. Condition World Wide. T have dwelled upon this founda- mental cause of Germany's difficulty because the condition in varying degree is world wide. It exists here in Amer- ica. If it should continue to exist in such extreme degree it will give rise to excmxxl politics. As one result we shall ortly hear of political devices for cheapening the dollar, for increasing the number of dollars, for making dol- lars easfer to get. We shall hear, among other things, projects for minting great quantities of silver into dollars. And other projects for printing the words “one dollar” on pieces of green paper without reference to the paper being transferable into gold. ‘The condition here described and now existing in relatively mild degree ex- | isted in more severe degree in the United States intermittently from after the Civil War until about 1896. It gave rise to a long series of national political contests cent g about the size of the dollar, to the “greenbackers” (meaning those who favored an abundance of pa- per money), and the “free silverites” and their opponents, the “gold bugs.” book of his and wonder of what a kind | It should said at once that there he was. Well, let that much of im-| mortality console him. It is all that most of us will get, and it is more than | is granted to most mortals. But fame! | No, I don't think that most men write | novels for fame. We live in an ironic | age. ! Rules Out Monetary Gain. For money, then? Ah, that is the common solution of this puzzling riddle. “Of course they write for money.” But do they? The best novelists most cer- tainly ‘do not. George Moore, John Galsworthy, John Masefield, E. M. Fors- ter, Virginia Woolf, D. H. Lawrence, Aldous Huxley, the Sitwells—it is be- yond any question that these writers have for years been doing exactly the opposite! “If any one will tell me that The Brook Kerith,” “Swan Song,” “Reynard the Fox,” “A Passage to In- dia,” *“Mrs. Dallowa: ‘The Pl d Serpent,” “Point Counter Point.” 11 in & Summer Day” or “Dumb Animal” —that these books were written for | money, well, the absurdity at once laughs in your face! But I will go farther and say that no novelist ever yet wrote a real novel for money. He may, of course, have a theme, & ter, a situation and think 1f: “This should be suc- has once truly n_cal middle of the world of his stop and consider his public. I know one novelist who, for some years, has so invention, to | to is no necess: reason to suppose we shall have this kind of radical move- ment in America. There is no necessary reason to suppose the present high value of the dollar or the present low prices of commodities will continue indefi nitely. If anything, the weight of prol ability runs the other way—toward a more normal value for the dollar, a more normal price range of commodities and a more normal relation between the two. For one reason there is now in the United States just about half the gold in the world. It is more gold than we or.any other nation has had before. It is more gold than we need or want. We ‘would prefer not to have so much. Other nations for a variety of causes, thrust it upon us. Gold Lowers Value. ‘The bearing of this- excessive stock of gold cn what has just been said is this: Almost invariably, the presence of so great a stock of gold results in re- ducing the value of the dollar and causing prices of commodities to go up. A rise in the prices of commodities may be more closely ahead of us than we_suppose. People have short memories. The present and recent ccnditions. the rise in the value of the dollar and the de- cmum l:lu t;ga prices of eommgw. ge! accompany. n, has occurred before, ‘nfin the mem- ory of every adult. It occurred in 1919 extremes and 1920. It went to it_had ample, can double within the space year, it did so as recently as 1926. | stitutions on ordinary 30 or 60 day notes |refused to renew the notes. The amounts ran into billions of dollars. | There was a run on the Reichsbank. the ‘equx\'alenb of what in the United Statés | would be increditable, a run on the Fed- | eral Reserve system. The flight of capi- ‘L!X and the paralysis of the German | banking system that had seemed im- | minent about June 10. would have led to |complete paralysis of industry, and | paralysis of industry would have led. so it was universally supposed. to a politi- |cal result which would consist merely | of & contest between Fascism and Com- | munism. Whichever might triumph the iemcx upon the world would take col- umns to tell. Governments Worried. The heads of government in every country in the world took alarmed no- tice, excepting Russia, where the Soviet leaders looked on in hopeful satisfac- tion. The heads of every national bank- |ing system and all industrial leaders | were almost panic stricken. What the collapse of the German Reichsbank would have meant to the banks and banking systems of the world (espe- clally France and Great Britain) can |only be imagined, probably, by those | familiar with ths fabric of world banking. | It was estimated at the time that |the American banks had least to fear. | It was thought, indeed, that the Amer- ican banking system would survive the shock fairly readily. But it was very | certain that the collapse of Germany, |followed by echoes in France, Great | Britain and elsewhere, would prolong |our business depression’ here. Had Ger- | many gone the way it seemed destined ‘lc go about June 15, America.could not have hoped to get back to normal pros- | perity for years to come. { Indeed. the consequences upon us |might have been greater than mere | prolongation of business depression. A ;member of the French cabinet in a ‘pubhc speech on June 14 said, “The world's situation is so serious that it is civilization itself which is at stake.” On the political side some foresaw Communism advancing to the Rhine. |Those who did not see Communism |advancing to the Rhine saw Fascism doing so. It was generally taken for granted that Germany as a republic was doomed, that it was sure to go either Communist or Hitlerite, the lat- ter meaning Fascism. The consequence to the whole world would have been sensational. Hoover Acts. It was at this crisis that President Hoover acted. That his action caused Startled surprise to America and the world seems, after the event, difficult |to grasp. President Hoover, of course, thad information not available to the public, Some day when the message of Presidemy Fmurnsurg to Mr. Hoover is published, as well as the other mes- sages that raced across the Atlantic, the world will know how imminert the crisis was. The average American, the newspaper reader in Spokane or Kansas City, had no faintest knowledge of what hung over. It was like the weeks ‘e- ceding the opening of the Oreat War in the Summer of 1914. This transatiantic telephone can understand now why the By every law of economics we should | War was not prevented. Hefe we a3v considered his public—or rather his editor. He is an unhappy man, who can find no longer any joy in his work. | which only the beginning is uncertain, Moreover, except for a I half- | an era of prosperity even greater than dozen, novel writing does not offer any | the one from 1921 to 1929. glittering money reward. This has been| The of the world-wide de- gone into so often that I will not em- | pression. together with natural repug- phn:l}:A it B:re. But it !’&I’.‘ money ’,fi nance fl: p-y{nl 80 much tnurvp-ruluna, are r, then, as novelist, prepare gave to two radical political move- l-imuhoodwm disturbing | ments in At an ejection in vel 5 1929 the Well.u'wfin.wmof»mmmm! strength - of the o have ahead of us now, at a time of crisis. 1y mmz-ni oo-operatio: can prevent it. And you ean see hard it is to get the co-operstice. Gl e T Didn't Kido Raflroad on the Do _you write your novels because you |one hand. and, on the other, the Hit- want _to do people good, because trans- | jerites. who are a kind of Gorman (Continugy on Third Page) equivalent ' of Italy’s