Evening Star Newspaper, October 26, 1930, Page 93

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

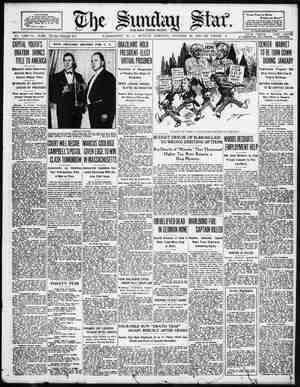

THE SUNDAY STHR, WASHINGION, D. C, 1936. = OCTOBER 26, 1% Proving Nero Didn't Fiddle W hile Rome Burned History Has Always MadeHim a Fiend, but the Emperor Was Not So Bad at T'hat, According to This Surprising Evidence,Which Shozos That HelW as Kindhearted and Loved by the Com- mon People and That He Did Not Set Fire toHis‘City. BY ARTHUR WEIGALL. EW characters in history have been so maligned as Nero, Emperor of Rome. You are no doubt accustomed to think of him as a monster of iniquity, a fiend incarnate, who callously murdered his his palace playing his mad music in the glare flames is perhaps impressed upon your b et t it is almost too much to hope that the absurd slander will ever new book, ‘“Nero, Rome,” I have done other emperor, and as -for this incident of his fiddling while his capital went up in smoke and flame—well, it simply did not happen. The fact of the matte two distinct sets of enemies, and the story of his life has come down to us from these tainted sources, and it is only by searching for and plecing together the isolated statements in his favor that I have been able to show the other side of the picture and to prove, I hope beyond question, that he was actually a kindly man of genius, a great artist and a great lover, driven by fate to perpetrate only some of those terrible deeds which have blackened his name. He was quite innocent of others, including this matter of gleating over the fire of Rome. OSEPHUS, the ancient Jewish historian, puts it in a nutshell when he writes that certain authors of his day “have so impudently raved against Nero with their lies that they them- selves are mcre worthy of execration than he.” These maligning authors all belonged to the aristocracy, and it was the aristocracy whom Nero so deeply offended by his unconvention- ality, and particularly by his insistence upon singing in public to his people like a profes- sional musician Nero possessed a marvelous voice, and, in fact, during the last years of his life was sing- ing at concerts almost every day, and naturally the old nobility thought that he was in this way ruining the prestige of the imperial throne. They had nothing good to say of him. But at the same time Nero also mortally offended the early Christians, for he supposed them to be villains who had set fire to his be- loved Rome, and he therefore punished them severely. It was the first “persecution” of the then small sect, and when, four years after this fire, the Apocalypse was written, which is the last book in the Bible, Nero was castigated in it as “The Beast,” whose number for 666— a cypher which conceals the name “Nero Caesar” (as all scholars now admit). In time the later Christian writers came to speak of him as Antichrist and as such he was the detested figure of medieval tales, and in this way all modern accounts of him have been based upon a prejudice which I have tried to expose and remove. ’]‘HE real story of the fire of Rome in A D. 64 is as follows: The Emperor was spend- ing the height of the Summer at his seaside palace at Antium, 35 miles from the city, when, during the night of July 19, A. D. 64, a con- flagration broke out in the wooden sheds and small shops at the east end of the Circus Max- | | “Thumbs down!” The Emperor Nero leads the Roman imus, at the foot of the Palatine and Caelian Hills, where great quantities of oil and inflam- mable materials were stored, and the flames and sparks, carried by the south wind, soon set the circus itself alight, for, after a long period of hot and dry Summer weather, the wooden seats and beams were like tinder. Thence the fire spread aiong the valley be- tween the Palatine and Caelian Hills towards the Esqualine, and also along the wider valley between the Palatine and Aventine Hills, and in either direction the dry woodwork of the crowded houses provided fuel for the blazd! The narrowness of the streets allowed the flames to leap quickly from the burning build- ings at one side across to those as yet unharmed on the other, while the intricate windings of the lanes and alleys carried the fire in un- expected directions. For six days the city blazed, and then, when the catastrophe was thought to be over, the flames broke out again and continued their - destruction for three days more. These nine days provided scenes of horror far transcending those when the smaller Rome of four and a half centuries earlier had been burnt by the Gauls, far transcending also those of the great fire of London in 1666 which lasted only four days. Panic soon took hold of the citizens, and during the first days of the disaster the con- fusion was appalling. The screams of the women and children, the cries and shouts of the men were incessant, and the noise and smoke, the crashing of the buildings and the heat and glare of the leaping flames bereft the people of their senses. Distractedly they ran to and fro, often finding themselves hemmed in when they had waited too long in h:'-lag the aged or infirm to escape, or in salvaging their goods. In the sudden panics and rushes which occurred as street after street was attacked scores of people were trampled underfoot or suffocated. Arthur Weigall, author of “Nero,” gives a new picture of the Roman Emperor. Scores more were burned to death as they attempted to rescue their friends or relations or to save their belongings, and it is said that many went mad and flung themselves into the flames which had destroyed all they loved or possessed, or stood dumb and motionless while their retreat was cut off. ADD]NG to the confusion, thieves were soon at work, assaulting and robbing the house- holders who were carrying their treasures into the streets, and Dion Cassius states that soldisss and police, bent on plunder, were The traditional Nero, singing his poem of the burming of Tavy while his own Rome burned. This great painting, by Edmund Bruninger, med others like it have fixed the popular idea of Nero in the public mind. people in giving the death sign for a defeated gladiator. Painting by William Peters, Norwegian artist. sometimes seen to set fire deliberately to tha houses of the wealthy so that they might steal the valuables which they were pretending to save. The flames early began to move up the east- ern and southern slopes of the Palatine Hill, on the summit of which stood that vast con- glomeration of buildings of various ages which smoke must have been blowing across the Palatine Hill from the around its southern slopes and which cut seems to have returned to the Forum and have made his way around the Capitoline and across the Tiber to that part of the: ty which was southwest of the conflagration and therefore free of smoke. private theater was situated. TRERE he had held his “Festivals of Youth,” and from ifs roof during the following days of terror he watched his palace go up in smoke and flame. The loss of hundreds of ancient books and documents of extreme value and interest, the destruction of paintings and works of art appalled and infuriated him. One by one he saw the famous buildings and monuments of Roman antiquity of which he had been so proud devoured by the flames. It was not until July 28 that the fire was finally extinguished, and by that time about two- thirds of the city had been reduced to ruinsg and ashes, and the losses in human lives, in property and in works of art and learning were incalculable. The measures which Nero took for the relief of the distress during the height of the blaze and afterward were regarded by his con- temporaries as very praiseworthy, He gathered the refugees together in that part of the Campus Martius which was free from danger, housing them in the Pantheon, the Baths of Agrippa and. other large buildings there situ- ated, and erecting temporary shelters for them in his own private gardens across the river, in what is now the Vatican neighborhood. As soon as the fire had passed from any area he placed guards there to protect the ruins on behalf of the owners of the property, and he instituted a search for the dead at his own expense. He brought up stores from Ostia and other towns to feed the homeless and he reduced she price of corn to bring it within reach of those who, though impoverished, did not need to be fed by the state. During all these days of horror he worked with indefatigable energy, directing these oper- ations and attempting to calm the terrified people, and although he had heard that those ' who had conspired against him on previous occasions were now taking advantage of the castastrophe to arouse hatred of him and to bring about his death by assassination, he went fearlessly about his business, appearing amongst . Oontinued on Thirteenth Page. ..., ..