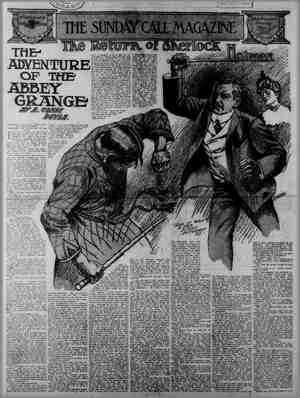

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, May 21, 1905, Page 4

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

THE SAN FRANCISCO SUNDAY CATT. The prize story for this week, 3 % “The Fate of a Cremona,” is by Miss Mabel Haughton Brown, Stanford *02. Miss Brown is one of the best known of the newgr i ¢ generation of college writers and % e s her literary work has aiready won for her considerable recog- nition. room mu X serves as Here he showed you 2 tower, in w ock of Swiss work- out the hour in chime- there he showed a silver elabrum with 2 naych’s crest; from & drawer he drew forty-six small daggers, and proceeded to give the history of each. The prices? He will tell them; but he will not = He shakes his head et each entreaty. “It is sold now.” he will say, or “I buy this myself for my wife Julia.”™ A stranger does not stare at the mention of a woman about the place, but & neighbor taps his head, and ex- plains later. “His 'wife, pever was.” Back of the shop is a small room furnished with table and chairs. It was here that Signor Domenico dis- pensed wine—rare Stuff of his own making, he would tell you. Here it was that he regaled the stranger who had come to buy. But the stranger, were he wise. had come with another object as well. “I drink to your fame, Signor Domen- jco. You will play for me, perhaps?"” It was then that Signor Domenico would straighten up, looking almost youthful under his assumed import- ance. He would go to a small hair-cloth trunk, stowed away in- & corner, and would bring out a black leather case. with dull hinges. He would handle it reverently, for the treasure it contain- ed outranked in value the contents of his shop. He stands back near the window, his long white beard flung Julia—she is not—she across his chest, the violin pressed agalnst his The first draw of the bow holds the listener spellbound. The old man not with his fingers, but with his A virtuoso! Signor Do ico—ah, where has one heard the name? t Domenico.” name is “What th 4 The signor frowns and shakes his head; he does not fancy the guestion. “¥You have played abroad—you were famous, perhaps?” Hie eyes glow now. He draws from his pocket a picture, as if he had placed it there for this express purpose. GHTON (3 “I have played for him.” he says grandly. By the uniform and by the orders you recognize a roval Personage. “The King," he tells you simply. Ah, the joy of it! Here is a man who can live, who can thrive and be happy—on & memory! And now will you look at his birds and flowers? He will speak quite freely of his wife a, the mythical companion of his age. 7 wifa Julia—she like always & bouquet in the window,” he tells you. bouquet is. there—white roses ys—with perhaps a touch of scar- anjum. Each evening the vase containing the flowers is carried ' up- L and is placed on a small ebon- ble beneath a picture. The room ly furnished (vastly different its present state); the floor is peted, the bed is carved, the hang- ings are of silk and mull. It is the Toom of his wife, Julia, he 1 you; but you must not enter. is not here now, she is away. You will come again perhaps, and may meet You draw back with unexpressed del- Is this, too, a memory, even more sacred than the other, you ask yourself, or is it but a vagary? You return to the shop. You observe now that his coat is threadbare.. Can it be that he experiences poverty in the midst of luxury? You long to drop a coin on the counter; but his glance forbids. You have had your entertdin- ment, will you now insult your host? You express your thanks in words. He bows profoundly. He. opens the door to let you out. As you pause by the window a moment you observe him k at his brasses, a contented smile n his lips. So he passes from your ken, and you from his. T an But a tragedy little shop, is to be enacted in a tragedy none the bitter because it is commonplace. is the tragedy of poverty that must me do violence to the old man’'s cannot live forever polishing brass and entertaining strangers. One must have coin as well. The time has come for him to dispose of some of his curios. But he does not sell them to s; instead, he pledges them with Jews, receiving only one-tenth of their price, and sometimes not so much. What do these Hebrews know of the value of such wares? But all the better, he thinks; they will be that much easier to redeem when the time shall come, Ah! the pathos of it! There is al- ways the ship that must come in for this old man. He has the blind faith of a child in his future. One by one the contents of the little shop are pledged; even Julia’s room is stripped at last of all save the vase and the pleture. It is now that the old man is grow- ing weak—too weak to care for him- self. Nelghbors are insistent in their attentions. One woman establishes herself part of each day in the little back kitchen to prepare the signor's meals. He has refused her ministra- tions at first; but in time he grows to watch for her coming as eagerly as he formerly watched for tourists. And it is all in order that he may play to her as played to them. Each morning the roses are gathered as before, and when the little garden grows bare So- phia brings them from her own yard and places them in the little vase, Between times the old man slips out and barters with the Jews for the tou ] i ! i j/ )/ T 3 1, s, ey Tars 2T WIFE , LA — 175, Fop SHE ZOVE'S, MENOW —~ 728, e £ pledging of smaller knicknacks he has kept till the, last, for Soppta herselt cannot afford the few pence she must spend for the stews she makes. Isaacs, the Jew, is crafty. “Some day you will bring -him—the fiddle, eh?” he a.sb. “I will give you much money—I will give you enough to live for months—eh?” The little Italian lgoks scared. “It is not for sale,” he answers, evasively. “It is not mine. It is of as the popular author. 884 If a story earns publication it the writer’s name. No story will be considered that is less than 2500 nor more than 3500 words in length. 3 length of the story must be marked in plain figures. In the selection of stories names will not count. The unknown writer will have the same standin As one of the objects of the Sunday Call is to develop a new corps of Western writers, no stories under noms de plume will be considered. The will be well worth mf wite, Tulla? “You do not sell’him—no! You lend him. 1 give you much moneys to keep him till you come.” Domenico shakes his head. “Not till the last,” he answers, The Jew shrugs his shoulders, “1 give you much moneys—much,” he tempts, “1 give you thirty dol- Jlars” v Domenico tHrows up his hands. “Thirty dollars! Only thirty dollars!"” Each Week for the Best,———— TORY The Jew realizes then that the old man knows the value of his ancient instrument. ‘Where did you get him?" he asks. “From her, my wife, Julia,” the Italian answers, her name ever ready on his lips. The Jew snorts angrily. “How long have you had him?"” he asks. But the lttle Italian is gone, shak- ing in every limb. That night he draws out his Cre- mona, tenderly, reverently. “The Jew wants this now,” he con- fides to Sophia. Her eyes fill. “You must go to the Jew no more,” she tells him. “You are too weak; you must let me go.” “It is old,” Domenico goes on in soft Italian. "It is older than she—older than I See, it is" worn there, and here is.a patch.” She looked at it pityingly. “You have had it long?”’ simply. “Nearly fifty years.” “Ah, and have kept it so good! You have been very careful. It still makes fine music,” she adds, consolingly. A cunning look is in his eyes. This woman - plainly. does not understand. He may trust her, at least. He drops back into English. “The Jew like it; he think it fine. Tt is my playing that make it fine—eh? eh? But he. offer me money—much money.” Sophia is seized with a sudden desire to cheat the Jew. “You sell ft—you buy a new one,” she hints, breathlessly. The oid man winces. “I want not a new one: It is of my wife, Julia,” he tells her. “Oh, yes; oh, yes.” The woman is all sympathy. Isaacs has not seen it close, perhaps— he has not seen the patch. He wlill see it and will know it Has been broken and will refuse to buy. Her avarice is stilled. “We shall keep it then until—" She stops short, on the point of mentioning a dread possibility. she asks Stories not uccepted will be returned at once. g Those selected will be published one each week, ® v ‘An author may submit as many manuscripts as he desires, but no one writer will be permitted turn postage. address legibly on FRANCISCO, Always inclose return postage. scripts will be returned unless accompanied by re- to win more than three prizes during the contest. vi No manu- wvit Write on one side of paper only; put name and last, page, and address to the SUNDAY Emgon OF 'THE CALL, SAN AL, ~ He clasps the violin in his thin arma “It is of my wife, Julia,” he repeats “She gave it to you?” It is the first time she has dared ask a direct question concerning his dream wife. His eyes are moist, he answers her softly: “She gave it to me—yes—it is hers—" He Lteaks off suddenly. “Listen, it is old; it will break soon— see; but I love it; it is mine, mine. It is her spirit—listen.” He draws the bow and plays a sweet, quavering melody, entirely.feminine. “See, see, she talks to me,” he keeps repeating. “It is my wife, Julla. Can you hear her voice? Listen.” The Italians are by nature romantic. The woman nods her head: she under- stands. But there is still her curiosity to be satisfled. “Your wife, Julia, the lady in the picture—is she dead?” she asks, falter. ingly. The melody ends in discord; his lips quiver. “You know, then—you know? . Oh, but you cannot know—no one knows.” The suspicion in his eyes fades away. “My wife, Julia,” he repeats wander- ingly, like a child playing make-be- leve. “She is not my wife, no; but she was - to be—no—no—I cannot tell—yes. yes; she is dead—that is it, is dead.” The woman stands irresolute, dtvided between her curlosity and her remorse at having Introduced the subject, Do- menico strokes the violin with his bow ever so softly. Its wall is that of a child crying in the night, Dbeseechingly plaintively. He quickens his movement, changes abruptly and brings in a strain from a‘famous opera. He is imitating the flutelike ‘tones of a woman's voeice. 1 die, thine fop ave. she 1. my love, shall die, sh But my heart: shall kve These are the words he interprets. Sophia sighs softly, vaguely. “And ‘was she very beautiful?” asks flnally, “and could she sing lke that?” “Ah, ten times more beautiful than this! She was the flower of all France, and I—I was nothing.” “Did you not play for her, then?” “No; ah, ne; we were children to- gether in Italy—and she forgot—but I, never. 1 sent her flowers—each time she ‘lang‘ clear to France—and my love —always my love— It was her wed- ding day—but not to me—and she sent me this—because I could play a little— and then—" “And then?” Sophla breaks in ea- gerly. ;i “She dfed,” he answers simply, sane- ly; “she dled with him—on the water— in a ship that went down.” He brushes his hand across his eyes. “It was after that I learned to play— so well that all Italy listened—aeven the King, the King! It was always on this —always on this.” He stretches forth his hands, clasp- ing the violin. “It is this, this that I call my wife, Julia—this; for she loveés me now— me, me!™ Sophia bows her head, eyes vigorously. “And all these years,” she sobbed, “and all these years—"" She breaks off suddenly and runs from the room. A few moments later she returns. “Dinner is served,” evenly. . She arranges his simple meal on a single platter, and stands behind his chair, serving him as she would -have served her sovereign. Crepe hung on the door of the little shop, a long black cloth, fastened with a /white rose. Isaacs saw it from a distznce and hastened to pay his re- spects. “I hatf come to get a fiddle—his fd- dle,” he informed Sophia. “I pay you if you get it,"” he added insinuatingly. “How much?” she asked curiously. “Four dollars—yes?” he ventured, watching her face. *“It is burned.” The Jew let forth a shriek. “Burned—who burned screamed. “f did.” “You! “You! You will be arrested— put in jai¥ It was a real Cremona— a Cremona! Do you hear? It was worth $1000—and more—more!” She looked at him pityingly. “No, it was old and worn out. He told me so, and he tcid me to burn it when he died. I did." She went into the little kitchen and bréught out the charred remains. “The Jew fell upon them eagerly, despair- ingly. He raised his hand and struck at the woman. 5 she wiping her she says un- e he