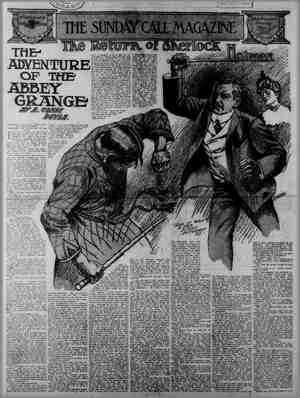

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, May 21, 1905, Page 3

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

THE SAN FRANCISCO SUNDAY CALL. nd the un- ld ques- ution. An e worth of if the friar » right., An behind him. longings been de- sting. In away beside 1 tried—and blow he might was in straits best, given his Teresa. wouid s. Must her ays bitterness? of life past re- pit th emotion the others turned will g0 back Go to my wife—you will —say—" indistinct and r. Only frag- zuished sister”— s flashed into he valet nwonted- cordato derly who had hev not d What is up with was not coun- exhaustion ad pillowed won- y pass- after one The friar in Wand, The door nba wec silently which had voiced resa had made no s ed Gordon’s head in N face with a the court »{ many people, of voices; Somalian’s rom No brow, and again like blue- warmed the cold own she had de when her arms iy, bleeding from a s declining and the air 1 v shadows. The storm that v had begun to mut- ff thunder, and the made a lurid flame Gordon stirred t length opened his are. He heard the , like distant artil- of delir k wild uage um he sat y, in a sin- Forward! ke for Greece! weakness had eme desire. He was on Lepanto. e friar's voice spoke— ictories than of war. the agony and the ds seemed to stri’ » through revered fantasies n. The dying man's eyes the speaker with a vague e was silence for a mo- side the chamber a griz- knelt by a group of offi- ed f wet with tears, ard rose the plaint- ening abyss of Gor- crumbling memory old recollection that Out of the s which a voice like very man bears Calvary. He saw beyond. ¢ brain struggled to recall. He saw dimly the the friar's hand held— hat had hung always er somewhere in a fading e of his. It expanded, a sad, vary against clive foljage e ashes of the Gethsemane y—the picture of the ternal suffer- { the Prince of Peace. but thine.” words fell faintly from the wan Jlips, scarce a murmur in the room. Gordon's form, in clasp, seemed sud- denly to grow chill, She did not see the illumination that trans- formed the friar's face, nor hear the »pen to her brother and Mavro- ato. She was deaf to all save moan of her stricken love, blind to all save that face that was slipping from life and her. Gordon’s hand fumbled in his breast end drew something forth that fell rom his merveless fingers on to the doc bed—a curling lock ¢ baby’s hair and a worn fragment ¢ er on which was a written prayer. She understood, and, lifting them, laid them against his lips His eye smiled once into her his face turned wholly to her, a her breast. “Now,” he whispered, “I shall to sleep.” A piteous cry burst from Teresa's art as the friar leaned forward thére was no .answer. George Gordon's eternal pilgrimage had v gun. R LXIIL The Great Silence. Blaquiere stood beside Teresa in the windowed chamber which had been set apart for the courtyard. All in that Grecian port knew of her love and the purpose that had upheld her To the forlorn grief seemed a tender intimate token of a loss still but- half comprehended. It had sur- rounded her with an unvarying thoughtfulness that had fallen gently across her anguish: She had listened to the muffied rumble of *cannon that the wind brought across the marshes from the stronghold of Patras, where the Turks rejoiced. She had seen the palled bier, in the midst of Gordon’s own brigade, borne on the shoulders of the officers of his corps to the Greek Church, to lie in state beside the re- mains of Botzaris—had seen it borne back to its place amid the wild mourning of half-civilized tribesmen and the sorrow of an army. The man she had loved had carried into the Great Silence a people's wor- ship and a nation’s tears. Now as she looked out across the massed troops with arms at rest—across the crowded docks and rippling shallows to @ her, overlooking \,,' — 7 - i X Q://// GorDoN GOES < the sea, where two ships rode the swells side by side, she hugged this thought closer and closer t0 her heart. One of these vessels had borne her hither and was to take her back to Italy. The other, a ship-of- the-line, had brought the man who stood beside her, with the first install- ment of the English loan, It was to bear to an English sepulture the body of the exile to whom his country had denied a living home. Both vessels were to weigh with the evening tide. Blaquiere, fooking at the white face that gazed seaward, remembered another day when he had heard her singing to her harp from a dusky gar- den. He knew that her song would never again fall with such a cadence. At length he spoke, looking down on the soldiery and the people that waited the passing to the water-side of the last cortege. “I wonder if he sees—if he knows. as I know, Contessa, what the part he acted here shall have done for Greece? In his death faction has died. and the enmities of its chiefs will be buried with him forever!” Her eyes turned to the sky, reddening N\ ZULGRIFTAGE, PN A now to sunset. “I think he knows.” she answered softly. Padre Somalian’s voice behind them intervened: ‘“We must go aboard pres- ently, my daughter.” She turned, and as the friar came and stood looking down beside Blaauiere. passed out and crossed the hall to the rcom wherein lay her dead. She approached the bier—a rude chest of wood upon rough trestles. a black mantle serving for pall. At its head, laid on the folds of a Greek flag, were a sword and a simple wreath of laurel. A dull roar shook the-air outside—the mingte-gun from the grand battery firing a last salute—and a beam of=fading sunlight glanced through the window and turned to a flery globe a glittering helmet on the walil. Gently, as though a sleeping child lay beneath it, she withdrew the pall'and white shroud from the stainless face. \ -7 ,a’ She looked at it with an infinite vearn- ing, while outside the minute-gun boomed and the great bell of the Greek church tolled slowly. Blaguiere's words were in her mind. Do you know, my darling?” she whispered. "“Do you know that Greece lives because my heart is dead?” She took from her bosom the curl of flaxen hair and the fragment of pa- per that had fallen from his chilling fingers and put tlWem in his breast. Then stooping, she touched in one last fiipss the unanswering marble of his S, At the threshold she looked back. The golden glimmer from the helmet fell across the face beneath it with an un- earthly radlance. A touch of woman's pride came to her—the pride that sits upon a broken heart. “How bheautiful he was!” she said in a low voice. “Oh, God! How beautiful he was!” CHAPTER LXIV. “Of Him Whom She Denied a Home, the Grave.” Greece was nevermore a vassal of the. Turk. In the death of the ar- chistrategos who had so loved her cause, the chieftgins put aside quarrels and buried private ambitions—all save one. In the stone chamber at Misso- longhi wherein that shrouded form had lain, the Suliote chiefs swore fealty to Mavrocordato and the constitutional government as they had done to George Gordon. Another had visited that chamber be- fore them. This was a dark-bearded man in Suliote dress, who entered it unobserved while the body of the man he had so hated lay in state in the Greek church. Trevanion forced the sealed door of the closet and examined the papers it contained. When he took horse for Athens, he bore with him whatever of correspondence and memo- randa might be fuel for the conspiracy of Ulysses—and a roll of manuscript. the completion of “Don Juan.” which he tore to shreds and scattered to the four winds on a flat rock above a deep pool a mile from the town. He found Ulysses a fugitive, deserted by his faction, and followed him to his last stronghold, a cavern in Mount Parnassus. But fast as Trevanion went, one went as fast. This was a young Greek who had ridden from Salona to Mis- solonghi with one Lambro, primate of Argos. Beneath the beard and Suliote attire he recognized Trevanion, and his brain leaped to fife with the memory of a twin sister and the fearful fate of the sack to which she had once been abandoned. From:an ambush below the entrance of Ulysses’ cave. he shot - his enemy through the heart. On the day Trevanion’s sullen career was ended, along the same highway which Gordon had traversed when he rode to Newstead on that first black home-coming, a single carriage fol- lowed a leaden casket from London to Nottinghamshire. . WHAT HAPPENED « the GOOD EXAMPLE "NCE upon a time there were two brothers more or less related in blood, but not in anything else. The eldest, who rejoiced in the euphonious cognomen of Reginald, was everything. that his name would have prepared you not to expect. The psy- chology of names is too deep a subject for my feeble intellect to penetrate at this stage of the game, but if I only had time to go into it properly, say an hour and a half some afternoon. I am sure that I could discover profound and far-reaching truths of tremendous importance to the human race. At any rate, it is a very peculiar state of af- fairs that no one should ever expect anything but sugar-coated perfection from a young gentleman struggling on- ward and upward bearing the name of Reginald. Personally I am of the opin- fon that if my sponsors in baptism had inflicted any such indignity on me I should have lived only to get even with them, if T had to start a magazine and expose them in order to satisfy my thirst for revenge. However, as I remarked some time ago, Reginald had a brother. This brother’s name was John. Now if there is one name in all this world of care which is calculated to arouse confidence and a childlike trust in the honesty and intelligence of the wearer of it, it is John. Even Theodore is no better than a fair second with John, and Alton is hopelessly lost in ‘the dust. As Reginald and John grew to man- hood it was clearly discerned by their parents and admiring friends that the former was destined to contribute ma- terially to the gayety of the town, es- pecially around midnight, and, would probably add largely to the stock of carmine in which the community was shrouded for a good part of the year. On the other hand, and eyen farther away than that, there was John. John was undeniably designed by nature to be a comfort to his parents and a prop to their declining years. Every single night found him planted close beside the family hearth reading Macaulay or the Narth American Review. He never stayed out after 10 unless the executive committee of the Young Men’s Christ- ian Association sat unusually long in extra session, debating the advisability of serving coffee or cocoa at the next sociable.. Take it all in in all. John was everything that a son should be. Time flowed along as it has been in the habit of doing for lo these many years and Reginald and John pursued their customary vocations and avoca- tions with varying degrees of assidulty and success. His parents did not know it, but John had been looking with a brotherly eye upon the ways of sin in which the feet of Reginald were stray- ing, and taking counsel with himself as to how he might best persuade them therefrom. The result of these careful cogitations was an announcement one evening that-he infended to sally forth with Reginald and/8ee if he couldn’t win him from his evil courses by de- grees. Reginald didn’t .seem particu- larly excited over the prospect of be- ing coaxed into couldn’t very well make a kick in the presefice of the old folks. As‘soon a8 they were out of sight of the house he demanded to know what was up. Being naturally a suspiclous righteousness, but he * individual and having seen more or less of the world here and there he wasn’t at all taken in by John's polite talk about saving his brother from the evil one. John put a good face on the matter.and informed Reginald that he considered a knowledge of the other side of life as an essential part of a liberal education; it didn’t seem to bother him at all when Reginald de- manded to know why he ‘considered him a competent instructor in the ways.of life on_the other side of so- clety. - “What do you take the for,” inquired Reginald in cutting accents, “an amateur guide to Chinatown or a plain - clothes’ man in disguise? Can ‘your feeble intellect grasp the idea that I don’t know any more about the ways of sin—that is, real, dyed in'the ‘wool sin—than you do? If you think I'm going to have any scion of the Association for the Feminization of the Young Men of America grabbing me by the coat tails every time I fail by the wayside for a quiet game of podl or sit -into an inoffensive seance of penny ante with a 5-cent limit, you're distinetly barking up the wrong tree, Back to the firéside for.yours. When I need a guardian I'll hire one from a ladies’ seminary who can take real care of me and see that I don't get run down by an automobile or injure my mind by reading too much exciting literature.” But John was not to be shaken. Far back in the innermost recesses of his alleged mind he was maturing a scheme, and Reginald’s assistance was nhecessary to its proper working out. Therefore he made that soft answer “which is properly supposed to take the keen edge off righteous indignation. All that he asked was that he might be allowed to accompany his dear brother and see that no serious harm befell him. It didn’t take Reginald more than three nights' to discover John’s little plot. The real secret at the bottom of his sudden interest in his brother's welfare was that he had grown weary of the life of peace and order and good work that he had been leading and was determined to do a litle busticating on his own hook. The discovery so shocked Reginlad that he reformed on the spot and went straight back home to take his brother’s place by the fam- hearth. (Copyright, 1905, by Albert Britt.) /;—., A N/ 4 / strangers who, In its course it passed a noble country-seat, the’ he=mitage of a wom- an who had once burned an effixy be- fore a gay crowd in Almack’s Assembly Rooms. Lady Caroline Lamb. diseased in mind as in body, discerned the pro- gsion from the terrace. As the hearse came opposite she saw the crest upon the pall. She fainted and never again left her bed. The cortege halted at Hucknall Church, near Newstead Abbey. and there the earthly part of George Gor- don was laid, just a year from the hour he had bidden farewell to Teresa in the Pisan garden, where now a lomely woman garnered her deathless mem- ories. At the close of the service the two friends who had shared that last journey—Dallas, now grown feeble. and Hobhouse, recently knighted and risen to political prominence—stood together in the lantern-lighted porch. “What of the Westminster chapter?” asked Dallas. “Will they grant the permission?” A shadow crossed the other’s coun- tenance. Popular feeling had under- gone a great revulsion, but clerical enmity was outspoken and undying. He thought of a bitter philippic he had heard in the House of Lords from the Bishop of London. His voice was re- sentful as he answered “The-dean has refused. The greatest poet of the age and country is dénied even a tablet on the wall of West. minster Abbey!"” The kindly eyes under thelr white brows saddened. Dallas looked out through the darkpess where gloomed the old Gothic towers of Newstead. tenantless, save for their raucous colon- fes of rooks. “The greatest poet of his age and country!” he repeated slowly. “After all, we can be satisfied with that.” AFTERMATH. Springs quickened, summers sped their hurrying blooms. autumns hung scarfet flags-In the coppice, winters fell and mantled glebe and moor. Yet the world did not forget. There came an April day when the circumstance of a sudden shower set down from an open carriage at the porch of Newstead Abbey a slender girl of seventeen, who had been visit- ing at near-by Annesley. K Waiting in the library the passing of the rain, the visitor picked up a book from the table. It was “Childe Har- old’s Pilgrimage.” For a time she read with tranquil in- terest—then suddenly startled: Is thy face like thy mother's, my fair child! Ada! sole daughter of my house and heart When last I saw thy young blue eyes they smiled, And then we parted—not as now we part, But with a hope. She looked for the name of its au- thor and paled. Thereafter she sat with parted lips and tremulous. long breathing. The master of the house entered to find an unknown guest reading in a singular rapt absorption. Her youth and interest beckoned his favorite topic. He had been one of the year by year in in- creasing numbers, visited the little town - of Hucknall—traveiers who. speaking the tongue in which Georze Gordon had written, trod the pave of the quiet church with veneration. He had purchased Newstead and had taken delight in gathering about him in those halls mementoes of the man whose youth had been spent within them. ‘While the girl listened with wide eves on his face, he told her of the life and death of the man who had written the book. He marveled while he talked. for it appeared that she had been reared in utter ignorance of his writ- ings, did not know that he had lived beneath that very roof, nor that he lay buried in the church whose spire could be seen from the mole. He waxed elo- quent as he told her how the xilded rank and fashion of London had found comfort in silence—how Tom Moore. long since become one of its complacent satellites, had read its wishes well: how he had stood in a locked room and given the smug seal of his appro- bation whjle secret flame destroyed the self-justification of a dead man’s name, the Memoirs which had been a last bequest to a living daughter. The shower passed, the sun came out rejoicing—still the master of the Abbey talked. When he had flnished he showed his listener a portrait, painted by the American, Benjamin West. When she turned from this, her face was oddly white; she was thinking of another portrait hidden by a curtain, which had been one of the unsolved mysteries of her childhood. On her departure her host drove with her to Hucknall Church, and standing in the empty chancel she read the marble tablet set into the wall: IN THE VAULT BENEATH LIE THE REMAINS OF GEORGE GORDON. LORD BYRON, THE AUTHOR OF CCHILDE HAROLD'S P! HE WAS BORN IN LONDON ON THE 22ND o RY, 1788 HE DIED AT MISSOLONGHI IN WESTERN 'REECE, ENGAGED TO RES’ ON THE 19TH OF APRIL. 1824 IN THE GLORIOUS A’ STORE THAT COUNTRY TO HER ANCIENT FREEDOM AND RENOW! 'N. HIS SISTER PLACED THIS TABLET TO HIS MEMORY. A long time the girl stood silent, her features quivering with some strange emotion of reproach and pain. Behind her she heard her escort's voice. He was repeating lines from the book she had been reading an hour beforex My hopes of being remembered are entwined With 1y land’s language: if too fond and far These aspirations i their scope inclined— It my Tame situld be. as my fortunes are, Of hasty blight, and duil Obiivion bar My name from out the temple where the dead Are homored by the natioms—Iet it be— And light the laurels on a loftier head! Meantime, 1 seek no sympathies, nor need; The thorns which I have reaped are of the tree I planted. They have torn me—and I bleed. My task is done—my song hath ceased—my theme Has died into an echo; 1t Is At The spell should break of this protracted dream. The llvl!h shall be extingulshed which hath t My midnight lamp—and what is writ. is writ. Farewell! word that must be. and bath been— A sound which makes us linger;—yet—tate- Ye! who have traced the Pligrim ' the seens Which is his last, if in your memories dwsil A thougbt which once was his, if on ye swell single vecollection, not in vain He_wore his sandal-shoon, and scallop-shel: Could he whose ashes lay beneath that recording stone have seen the look on the girl's face as she listened —could he have seen her shrink that night from a woman's contained kiss —he would have known that his lips had been touched with prophecy when he said: “The smiles of her youth have béen her mother’s, but the tears of her ma- turity shall be mine!™ - (The End) A