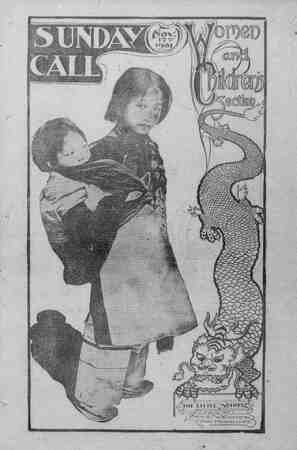

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, November 17, 1901, Page 15

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

funny name for a big, jack rabbit; but I was nor so long i when HAT 1s a long-eared not o b I 1 myself r a bunch h of a bed. beds as t have “lose beside me were two y were my I noticed they were had a dainty f each ear and sch large, long on their acks. broad They had a w two peas, and each like the other my bro into the world beau 1 world were in bloom; I high see, 100, the mountains snow n and fed us her we were came big stand throw in the night and and the alr was never was a little it there as I was my back, The grass I had gry than not yet le d to eat grass, and 1 was soon ent on and on, and then I neyard. I saw so was walking a He came my way did not know why I was fraid, in a furrow and He picked me up and 1 aid not like the And, oh, I was men g0 b ¥ e pipe In his pocket I would have gone to sleep. He gave me to a little girl who came running to meet him. and around with me to the h, Uncl Charlle, what a cunning, cute, fuzzy little thing it is.”” She held me up against her throat and talked baby talk to me. She sald: “O, e dacle! U, de dacle! pittie "ittle sing.” Her halr was 1 and llke gold and fell over her shoulders. I mestled to her throat and crept under her hair mearly to the back of her neck. She had her hands over me 21l the time so0 I could not fall. She kept cooing over me and calling me pretty names, but she &id not like me on the back of her neck. So she pulied me out from under her pretty. gold hair and cud- dled me under her chin again. I began to lick her throst. She laughed and cried out: and laughed, and s man: leve! This rabbit is a Mttle kitty, and it thinks I am cream.” Then I saw there was a boy coming toward us, and he called the little girl “Morris,” which was, I think, quite as o8d a name for a little girl as Fuzzy Fluff is for a jack rabbit. The boy was e pretty liitle lad, but there was a big dog with him, and I was afrald. The dog sniffed the alr andi made a leap to catch me. I thought he had me sure. The little girl screamed, and the little boy yelled: “Get out, Doc; get out! You rascal, And he caught the dog by the his neck and turned him e “somerset.” 1 wanted to laugh, but was afraid he would come after me again. e children took me to the house and me warm milk; they fed it to me a little silver spoon. In a few - v sat me down on the floor by a cer of milk and stuck my nose in it r that when they fed me I always t on the floor and lapped it out of a wucer. I learned from their talk that he little boy was the son of the people who owned the vineyard and the little girl was his cousin who had come from city a long way off to visit him; and t I belonged to the little girl, and she as going to take me with her when e went home. When I was older they e me a blade of grass to eat and called all the family to see me nibble it. I was fond of the children and not hair on at all when they held me in their , but the minute they turned me wild again, and they would me down or get me in a atch me. I suppose it was e to be wild. d been a pet rabbit for about two weeks two other little rabbits were brought to the house and put in my box ¥ were named Bunny and belonged to the little boy, ho was the youngest and a partnership rab- 1 it was that they saw how I d in had grown us, was color as I ow @ light, mottled, {rown- r, and the white spot on all gone. My eves, a were black in nd had a brown ring around They made a pen for us out the yard and put us into it to sieep. said wild rabbits slept out of doors we must sleep out of doors, too. ttle itz was not as rong as 1 1 were, and in the morning at on his side. He was d I thought he was dead. e to give us our break us on the front and took around in the sun. They took on a great poor Fritz. They rubbed his and head and tricd to put milk in his mcuth. The little girl said: *“His eyes are set.” She said it very sorrow- and I could see there were tears d the little boy, “he's kick. We'll make a cof- d bury him.” laid him in the sun and went They were gone a good while. When they came back they had a pretty box with a lid to it. They sat the box on the porch and went away without looking at me or Bunny or Fitz. I saw them go to the big locust tree that was the sifle of the road close to the almond orchard. The almond trees were ite with blossonms. They sat down t tree and began to dig. - were digging Fitz's grave, me back to the porch again ngements for the funeral are all took off the lid of the box and it on the porch, and went to get Fitz. 1 to myself at the sight of their here sat Fritz in a very natural when they stooped to pick him up he hopped off the porch, and they ran es. way after him and grabbed him by the hind legs just as he was going under the floor. They laughed and screamed, and the lit- tle 1 called: “Oh, Aunt Jen! Aunt Jen! the rabbit has come to!” . The woman she called came to the door and the boy said to her: z disappointed us.” “Well,” sald she, “you are not sorry, are you He smiled a funny little smile and said No; but it was a great disap- pointment.” A few days afterward I got out of the place they had for us in the corner of the yard and hid. Tke children hunted me and c3 d me and called me, and the lit- tle girl cried because I would not come back. I heard the little bog say to her: “Never mind, Morris; you can have my half of Fitzsimmons.” ‘When they gave up looking for me I slipped out from my hiding place and ran away. 1 had a very hard time for many days, and sometimes I was cold and hun- ery; and I was very lonesome. But 1 learned to gnaw the bark of the orchard trees and the joung vines, and to eat wheat and do many other of the things that make men want to kill jackrabbits. Once a dog took after me. I put my pars flat down on my shoulders and ran low and very fast—I ran for my life. He was a lean, hungry-looking greyhound.- He was just overtaking me; I could hear his breathing; I could almost feel his teeth in my body, when I tumbled heels over head into a badger’s hole, and the dog ran right over the top of me. The badger was not at home, and when the dog was gone I came out into the sunshine again, very glad to find myself allve. A year passed away. I was a full-grown Jackrabbit. I was talking one day with a very old jackrabbit, who was telling me about the country where we lived. He sald it was called Fresno County, and was the most dangerous place a jackrab- bit could try to live in. I was just on th2 point of asking him why, when he sprang up on his hind legs and stood his long ears straight up; it made him look very tall. I sprang upon my hind legs and put my ears up, too, but I could not see any- thing to be afraid of. Then I heard guns firing away off somcwhere and heard peo- ple shouting. Just then some rabbits came loping by us; their ears were ail thrown forward and they jumped so high 1 thought they were playing & new game. I asked the old rabbit what the noise was about and what the rabbits were doing. He did not answer, and then I saw that he was trembling all over, like one in a chill. I looked the way his eyes were fixed and saw & great many men and boys strung out in a line. They were about a rod apart and each one had a club in his hand—some of them had two clubs. A THE SUNDAY CALL dozen or more rzobits came running past us; they nearly knocked me over in thelr haste. “Follow me,” sald the old jack. He jumped high and started directly toward the men with the clubs. I thought he had lost his mind. I followed the rabbits that were running away from the men. ‘We ran on for two or three miles ani 'were soon over our fright. A great many rabbits were coming from behind us and from the right and the left of us. They came by hundreds, and it seemed to me were all making for the same point. 1 heard the firing again and the shouting. I ran up on a bigh knoll and sat as high as I could on my hind legs and looked back. Then it was that I saw. the great- est and strangest sight of my life, but truly hope I may never see the like again, An army of people were marching down upon us. They came In a semicircle. It must bave been two miles long at the least. The army was in three divisions. First came a’'line of men and boys on foot, each armed with a club; behind them was a line of carrlages and horse- men. The carriages were of every kind I had ever seen. The people in the car- riages were mostly women and girls; some of them were little bables. There were men and boys and young women oa the horses. Some of the young women wore bloomers and leggins and funny little caps, that did not keep away the sun, and rode prancing horses. Behind the line of carrlages came another line of men on foot; these men marched further apart than the others did and they carried guns, And in front of the whole circling army, from one end of it to the other, thére were men on horseback; each one of them had a long red, white and blue scart over one shoulder and tled under his arm at the other side; the ends of tha scarfs fluttered back on the wind as they rode. Some of them had a paper star pinned on their hat. They rode in a gal- 1op all the time, back and forth, back and forth, and shouted to the army until their volces were hoarse. Thelr horses were streaked with sweat and foam. They called these men the marshals; they kep: the moving army In a circle, and each wing of it in its place. There were more than a thousand people in that army. It was a grand sight. When a rabbit start-. ed toward the army the men and boys in the first row hurled thelr clubs at it; it they missed it, or only broke a leg and it got beyond the teams, the men with the guns shot it. And ever as they camo nearer and nearer they closed in closer and closer together. Soon. there would be a wall of people, beyond which no rab- bit could pass alive. I turned from look- ing at the advancing army and looked down at the rabbits below me. I had not known that there were so many rabbits in the world. For a half-mile square every way the ground seemed alive with hopping, jumping, frightened rabbits. I saw a long open space at either side of them, and wondered why they did not run out and get away. But a rabbit that came from the left wing told me there was & wire netting stretched for a half- mile along there, and a rabbit that had come from the right wing said it was tha same on that side. The shouting and the shooting and the tramping of men and horses came nearer. The rabblits were it terrified and began to run over each oth- er. Out of the thickest of them came a young rabbit I knew. We had gnawed the same apple tree one moonlight night; and another beautiful evening, when the mockingbirds were singing, we had played tag together. I thought of those happy times when she ran up on the knoll where I sat, and was going to speak to her, but she did not see me at all; she ran straight toward ‘the army. I called to her, but she did not hear me. I saw two men hurl their clubs at her. One struck her; she bounded high in the alr and fell flat, but jumped up and started again. One of her hind legs was broken; I saw it fiy up and down as she jumped. Another club was hurled at her; she tum- bled over and lay quivering in the grass. I heard the cry she gave, and knew that was the last of her. A rabbit only makes that cry when it knows the end of ifs life has come. A boy ran up and gave her a blow on the head. I turned away, sick at heart, and plunged into the crush- ing multitude of rabbits. Several clubs were hurled at me, but I was too far away. ‘We were crowded ahead and ran here and there, and round and round, and ran over each other, but always gradually moving in the same direction. Once I found myself on the tops of the other rabbits’ backs. I gave a sweeping glance around and then I saw how it was. The two lines of wire netting came together like the corner of a square, and the ends of the circle of the army touched the outer ends of the square and moved slow- ly along against the fence of netting. I saw that the army had closed in and be- come & solid wall. The first division of the men was down walking on their knees; thelr elbows toucked. And the marshals with the gay. fluctering scarfs galloped back and forth and shouted im front of them to keep them In place. Many rabbits were trampled under the horses’ hoofs.’ The shouting was terrify- ing. Suddenly I felt the struggling mass of rabbits give way. I slid to the ground and was forced along in the rush. I found out that the cause of it was an opening In the fence, #ight in the corner of the square and the rabbits ahead had broken through ft; the others all followed. My heart leaped with joy as I went through the opening in that fence. Alas! it leaped more wildly with fear when I got beyond it end-saw what it was. It was but the opening Into a corral—only a trap—see the cunningness of it? When I got into it, the rabbits were already piled up two or three feet deep against the fence all around the corral; those underneath were already smothered to death. Many of them lay down In the corral and died with fright. I stopped right in the middle of it. I could feel my eyes bulging with terror. I stood there in a kind of squatting pos- ture, every muscle quivering with fear, and watched the people come up and look, over the fence at us. One of the marshals called to the men to stand back and let the ladles look at the rabbits. After they had looked at us a while a man called several times for the boys to bring their clubs and get in and kill the rabbits. I saw them begin to come in through the gate that had been closed behind us. And I knew, unless a miracle should hap- pen, the end of Fuzzy Fluff had come. I thought of the sweet little girl who had cuddled me under her chin, of the kind- hearted little boy who kept the dog from killing me, and wondered why I had run away from them. The boys and men who came in at the gate had begun to kill the rabbits. The fur was flying; the alr was full of it. All at once I ran toward the fence and made & wild jump at the top of it. I struck it first at the top and fell back upon the pal- pitating heap of rabbits. I struggled to my feet; I felt a hand take me and lift me over the fence. A boy had me by the hind legs. He carried me out through the crowd of people and out to where the wagons were. He went to a carriage that had several people in it. He held me up before them and sald he was going to take me home. And then I saw it was the same little boy I had been thinking about. And one of the ladies In the car- riage was the Very same one the little golden-haired girl had called “Aunt Jen.” She said to him, “You can’t take it home,” but he stood looking down at me and dla not move. Another said to him: "x’u and take it home to the dogs.” He still stood and held me, it seemed to me a hundred years. I hoped he would know me as I did him and I wished I had never run away from his home. Never was a rabbit in such suspense. He held me up and looked at me; I thought he 4 TR T gk S P 15 was going to knock my brains out against the wagon wheel. Finally he said to me: “You look innocent; I don’t think yom ever ate much wheat.” Then hé swung me down at arm's lengih at his side: my forefeet touched s ground. I feit his fingers gradually loosen: I felt myself siiding down to the ground and mn I crouched under the wagon. T people were all off the guard. the ciubs were thrown dewn, the guns were empty—no one expected a ran- bit to escape after they were corralled. [ ran right undes the feet of the peodle and wasde— le say horses and hid under a bunch of saved and free. I heard some p¢ as they passed me going home thi.. it was a pretty good drive; they had killed 10,00 rabbits. I stayed hidden in the weeds t the sound of volces and guns, and wheels, and trampling feet had ceased. When the sun had slanted down into the west, and twilight was closing around the world, T slipped out, and away toward /(he high white peaks of snow. After some hours of traveling T came to the old ranch house where Buany and Fritz and T had lived. There were lights in the windows: the people had come home from the rabbit drive. It made me sad to look at the old place— the orchards, the vineyards, the great alfalfa fleld, and the big water ditch that ran like a river. Everything was the same except that where the locust tres was, vrder which the children had dug a grave for Fritz, I found only a stump and = pile of wood. I was looking at it and thinking of that other time when another rabbit hopped around the stump and nodded to me. To my joy I found out that it was my old friend Bunny. I told him about the rabbit drive and that I had made up my mind to go to the foothills and live. He said he would go with me, and that we would Hve together; it made me very glad. There are no beautiful wate hes there, no such flelds, and orchards and vineyards, and they say lae coyotes are on the watch for jackrabbits; but I would ruther take my luck among tke coyotes forever than in another rabbit érive. So, to-night, when the dogs srs asleep, and the big, round moon rolls up over the Sterra Nevada, we wil start for the foot- hills. THE CDD STORY OF R SPIDER. HAVE considerable resp tor the female spider, notwithstanding the fact that she does not treat the male very considerately. I had an oppor- tunity last summer to watch a large one that had a web in the top of a decaying peach tree with so few leaves that it was in plain view. I caught sight of her when watching some birds with my glass. She seemed to be climbing from the top of the tree on nothing to a telephone wire some fifteen feet away and somewhat higher than her web. When she reached the wire she went around it and then back. In studying the situation I found the web was so located that It required a cable to hold It up, and the spider had in some way got one over the wire so far away. This cable was, of course, a slender silken thread which evidently she had thrown out, and on account of its lightness it had floated to the right place and became at- tached there by its glutinous properties. It seems remarkable that it should have adhered to the wire firmly enough to al- low so large an insect to climb over it, which she did every day as long as I watched her, evidently -to mend or strengthen it. The gspider must have brains in which the ability to construct its web and adapt it to conditions is highly developed. In an article in Cham- bers’ Journal the following account of how the spider forms its silken threads is glve: e of the most Interesting features in the economy of spiders is their power of emitting slender threads of a silk-like substance called gossamer, with which most of them construct mesh-like nets, and a few long, dangling cables, by which they are buoyed through the alr with nearly as much facllity as though they had been furnished with wings. The ap- paratus provided by nature for elaborat- ing and emitting this gossamer is a deau- tiful plece of mechanism. “Within the animal there are several little bags or vesicles of a gummy mat- ter, and these vesicles are comnected with a circular orifice situated in the ab- domen. Within this orifice are five little teats or spinnerets, through which the gossamer is drawn. It must not be con- cluded, however, that thers is only one film of gossamer produced by each the fact is these teats are i small/for the naked eye to perceive, and each of these emits a thread of incon- ceivable fineness. These minute tubes are strands of ropé to form the thread of gos- samer by which a spider suspends itself, The finest thread which human mechan- ism can produce is like a ship’s cable com- pared with the delicate films which flow from the spinnerules of the largest spider. The filris are all distinctly separats on coming from the spinneret, but unite, not by any twisting process, but merely by their own glutinous or gummy nature. Thus the spinning apparatus of the dis- dained spider, when viewed by the eye of sclence, becomes one of the most won- derful pleces of animated mechanism known to man. The insect has great command over this apparatus and can apply it at will as long as the receptacles within are replenished with the gummy fluid, but as soon as this gum is exhausted all its efforts to spin are fruitless and it must wait until nature, by her inscrutable chemistry, has secreted it from the food which is devoured.—Phrenological Jour« nal.