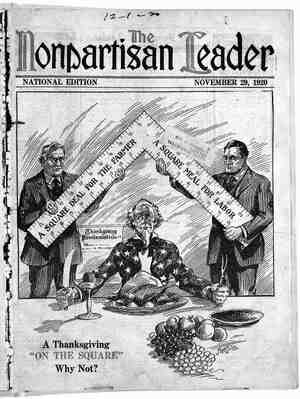

The Nonpartisan Leader Newspaper, November 29, 1920, Page 10

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

Big Business and the BiggeSt()f All Farm Wealth Makes t BY ORIN CROOKER =21 GRICULTURE is responsible, perhaps, | for the making of more millionaires in industry. - One seldom thinks of it in_ -this light for the reason that compar- atively few of these men of millions are agriculturists themselves. Their wealth has been accumulated through skilled exploitation of the fruits of husbandry, through trafficking in the products of that toil which is represented by wheat, cotton and other staples or by the raising of food animals—in short, through the “handling” of those products which have had their origin close to the : soil. f Scan the products of industry and note the sur- prisingly large proportion of them that center ei- ther in foodstuffs, im the raw materials that enter into clothing, or in other products of agricultural labor that find utilization in some line of manufac- turing. The valuation of the products of all indus- tries in this country amounted in 1914 to the huge sum of $24;246,435,000—the figures for that year being more nearly representative of mor- mal conditions than those of the subsequent war-time period. Fully one-fifth. of this ($4,816,709,000) might be covered by the single word “food.” More than one-seventh of it ($3,414,615,000) could be included un- der the term “textiles”—woven fabrics manufactured from the cotton and wool produced for the most part on American farms;-while under “leather” might be listed the sum of $1,104,5695,000, represent- ing still another phase of industry that harks back to the soil, regardless of whether the hides in question had their origin at home or abroad. The sum total of industrial products in this country which have their beginning in labor that is dis- tinctly agricultural exceeds $10,000,000,000 a year, or two-fifths of the total products of industry of more than 100,000,000 peo- ple. TEN BILLIONS FROM FARMS; WHO GETS IT? This $10,000,000,000 a year covers the operations of no inconsiderable portion .of what is commonly known as “big busi- ness.” It includes the packing interests, the milling interests, the sugar refineries and the extensive manufacture and han- dling of dairy products. It includes, also, the production of woolen and cotton cloth- ing, as well as leather goods such as boots, shoes and harness. It covers the manufac- ture of confectionery, a large part of the soap, fertilizer and canning industries, to- gether with the tobacco business and a host of lesser industries too numerous to specify. In every one of these many lines one finds examples of the “machine-made millionaire”—men who, through utilization of the products of agricultural toil, have built up fortunes of plethoric proportions. On the other hand, comparatively few of those engaged in the actual sweat and phy- sical hardship incident to such toil have succeeded in gathering a competence at all comparable to that which has rewarded the efforts of “big business” in its conversion of the fruits of husbandry-into specialized products of a thousand kinds. Three or four years ago a small group of farm- ers in southern Wisconsin did some figuring in re- gard to the material possessions of men in their immediate vicinity who, likewise, were engaged in agricultural pursuits. It was found that where a man had been farming for himself for 10 years on a farm of his own he was about $10,000 to the good. . Where he had put in 20 years ona farm of his own he had accumulated about $20,000, while in the case of the older men, 30 years of farming was re- flected in profits of about $30,000. There was but one instance where an average profit of $1,000 2 year did not approximate the real truth of the situ- ation. ' However, while a profit of $1,000 a year . seems small in comparison with the returns re- ceived in industry by men who are operating their own businesses, it should be remembered that this - this country than is any other line of ‘role of a producer. Who Gets the Profits? figure is really considerably larger than the average throughout the country. It is accounted for by the fact that this particular agricultural section of ‘Wisconsin is one of the best developed and most progressive in a state that ranks high among oth- ers in this regard. Realization of the relatively small returns to be obtained directly from .labor and capital invested in agricultural pursuits has been a mighty factor in developing the new viewpoint which is gaining such headway among those whose life effort is cen- tered on the soil. Although agriculture is con- cerned fundamentally with production, the new viewpoint reveals that the farmer has made a mis- take in the past in being content merely to fill the In doing so, he has made it possible for a host of middlemen, jobbers and spec- ulators—the last of whom harvest where they have not sown—to make a football of the fruits of agri- cultural labor. The necessity of direct marketing has become evident so far as the machinery for do- ing this profitably can be perfected. Another fact of importance has begun to impress | WHY FARMERS DON'T GET RICH | A8 —Drawn expressly for jtself upon the agricultural consciousness. Meas- ured by its invested capital, agriculture represents the biggest of big businesses. The value of farm land in this country (1910 census) is set at $28,- 475,674,169, Farm buildings represent an invest- ment of $6,325,451,5628. Farm implements are val- ued at $1,265,149,783. Livestock, poultry, ete., amount to. $4,925,173,610. Here is a total invest- ment of $40,991,449,090. The 1920 census promises to nearly double these figures. This is a staggering total—beside which the $5,000,000,000 capitaliza- tion of the steel industry, for instance, sinks into insignificapce. Looking next at production, it is found that farm crops had a total valuation in 1918 of $13,479,000,- 000. Animals and animal products added $5,682,~ 000,000—a total result from agricultural toil of $19,331,000,000. TIn such figures as these might be seen the making of a good many millionaires were it not for the single hampering circumstance that the profits of this business must be divided among. PAGE TEN the Leader by W. C Morris. he Wealth of the Steel Trust Look Small—But ) a host of stockholders. To the man who senses the fact that he is a participant in business of such proportions there must come some realization of its votential power. Were it organized, unified and systematized, as is the case with the different other phases of “big business,” no man would dare say what power it might wield for the good or ill of -our-social order. Were it to follow profiteering methods—as has been the case so flagrantly of recent years in the instance of “big business”—there is no : question but that our economic fabric would be torn to rib- bons in short order. Operated, however, with a view of bringing agricultural products more di- rectly to the consumer, and at a saving over the prices exacted by a host of middlemen and specu- lators, it must, on the other hand, become one of the greatest forces for human betterment that has been witnessed in mapy a year. Agriculture is the basic industry upon which all civilizations rest. Only when this basic industry is - freed from its chains will our Anglo-Saxon civiliza- tion come within reaching distance of its greatest possibilities. It is not to be expected that “big busi- ness,” which derives so much of its power from the lack of organization and co-oper- ation prevailing among those who consti- tute the “biggest of big businesses,” will surrender its hold upon agriculture with- out making a strong fight. However, the possibilities are vastly in favor of this sur- render being one of the certainties of com- ing years. . & “Big business” can not swing the pro- ducing end of agricultural industry. It has no callouses upon its hands! Produc- tion, therefore, must ever remain in the hands of those who man our farms. This fact alone, in the eyes of those who sense fully the keenness of the struggle before them, amounts to an assurance of victory. FARMER A BETTER PRODUCER NOW The history of production assures us of what may be expected in the case of dis- tribution now that the farmer has had his vision both strengthened and broadened. The average farmer of 1920 is a better producer than the average farmer of 1910. This is proved by the meaintenance of pro- duction in the face of a 10 per cent de- crease in farm labor. His mastery of pro- duction foreshadows his mastery of dis- tribution. Rightly enough, the farmer recognizes that he has much to learn before he can handle the distribution end of his big busi- ness as successfully as can those who have been engaged wholly in these lines while he has been devoting himself solely to pro- duction. Yet he has found in the methods of “big business” a practical suggestion for grappling with this particular prob- lem. California fruit growers successfully applied “big business” methods when they paid $17,500 for the service of brains skilled in salesmanship and merchandising. - The Nlinois Agricultural association is op- erating on the idea that $15,000 is none too much to pay for competent service with which to head its various departments. - In short, it has dawned upon the stockholders of the big business of agriculture that many of the highest-priced experts in mer- chandising employed by “big business” have come originally from the farm. These self-same stock- holders are now asking each other why they did not themselves employ such men years ago instead of letting them sell their talent to those who have 9xploited agriculture and have waxed fat in do- ing so. ; When the stockholders in the big business of ag- _riculture shall have fully perfected the selling end of their operations, it is to be anticipated that not a few of our present-day problems will be: greatly modified if not solved altogther. A decreasing pop- . ulation in the rural districts, the shortage of farm labor—even the scarcity of dwellings in the cities— can be traced back to the fact that agriculture ha e (Continued on page 16) P /L(oflqc r