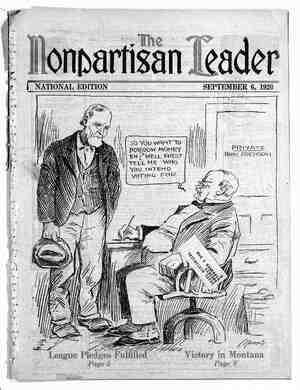

The Nonpartisan Leader Newspaper, September 6, 1920, Page 6

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

s Squeezing the Western Apple Grower Fruit Rots on Trees and on the Ground While ““Big Five” Closes Markets and Takes Over BY CHESTER W. VONIER %] POKANE, Wash.—Of all the branches #| of farming, none is more highly spe- cialized than the fruit industry. A rigid routine-of care is enforced if the grow- ers are to keep their orchards in bear- ing condition. Perhaps in no other branch of farming are there as many men in pro- portion'with more than ordinary education as in the fruit country. College men are common on these apple and cherry ranches. Men from many walks of life in the cities—physicians, professors from col- leges, men who have been successful in other walks of life—have tried it. And all of them come vp against the same stone wall of the markets and the market masters. At the Nonpartisan league'state convention in Yakima I talked with some of these men. Let me add - here that most of the men of this type of which I speak, the educated men, are ardent Leaguers. Com- ing up against the solid facts of the case, they have, a'most without exception, seen that the only way out of the wilderness for them lies in political action. One of these men with whom I talked has been a college professor. In fact, he has been president of the University of Oregon. He has been a high- calaried editor on a Portland paper. He came to Yakima as a delegate from Cowlitz county, down in the southwestern corner of Wash- ington. ‘This is an immensely fertile valley on the west side_of the Cascade mountains. He went there to raise cherries. He planted his trees and cared for them until they came into bear- ing. It was hard work, and into the venture he put long hours of work and a great deal of money. Then he began to market his cherries. But there was no compensation for the years he had spent in bringing the orchard into production. There was no compensation for the money he had expended in the venture. There was barely enough to meet the cost of harvesting and packing the cherries and sometimes not enough for that. : In the fruit markets of Washington cherries are a glut on the market. They are usually so at this time of the year, yet in the East they bring 35 cents a pound. The cherry grower saw.all these things. The orchard to which he gave his time and his The larger picture is that of one of the numerous government irrigation projects in the fruit coun- try of the Pacific Northwest. The smaller picture is of the harvest.in a Pacific Northwest fruit or- chard in a good year.(infrequent enough) when it pays the fruit farmer to harvest all his crop and offer it on the privately con- _ ‘trolled ‘and juggled market. energy is now neglected. The trees are no longer sprayed, the ground is no longer plowed between them. The ranch is given over to an attempt to make it into a dairy farm, because cherries didn’t pay. And why didn’t they? The answer of another fruit raiser, the owner of an apple orchard in Klickitat county, one of the south- ern tier of counties which border on Oregon, might be of interest. This valley also is fertile. It requires no irrigation. The crop this year will be good. Conditions have been ideal for the fruit men. Yet they are looking forward to a big loss on their crops. FRUIT GROWER IN GRIP OF THE MONOPOLIES This grower, with whom I talked, has fought the - market in every way he dared. One year he made money. How? Let me tell you. He took his ap- ples—carloads of them—1,800 miles to Minneapolis. There he rented a vacant store on the corner of Sixth street and Nicollet avenue and sold his fruit direct to the consumer. And even then he ran into the hands of the market masters, who didn’t want him to set a bad precedent. He tried to advertise his fruit in the Minneapolis Journal on their weekly home market page. He contracted for a certain amount in a certain posi- tion. He got half the amount of space for which he contracted and his ad never did get on the home market page. 3 This year he is facing the problem of how to market his apples on a paying basis. He will have to pay vastly higher freight rates, so that the rail- roads may approach a profit of 6 per cent on their. $13,000,000,000 of watered stock. He is facing the problem of buying boxes, when : the fruit box supply in Washington and the entire - West is in the hands of a. monopoly. And this monopoly- is in the hands of some five concerns in Chicago, whom A. Mitchell Palmer refused to prose- cute, because he believed they meant to be good! This monopoly is the packers. 3 He is facing the problem of getting paper to wrap his apples. Paper, too, is in the hands of monopolies. _ He pays higher for potash and nitrate for fertiliz- Farms in Competition With Small Producers Among the folks of the Middle West fruit is becoming almost a prohibitive luxury. Though “an apple a day keeps the doctor away,” if we are to credit some homely sage, it is cheaper to call gle doctor than to follow the prescrip- ion. . ' Yet in the West, “golden land of op- portunity,” apples are rotting, or will rot, and bending boughs, loaded with cherries, are mnever touched by the hands of the picker. It isn’t worth while. The canneries will not pay enough for cherries to cover the labor cost of harvesting the crop. But ‘in Minnesota and North Dakota, in Wis- consin and Nebraska, these same cher- ries are bringing 35 cents a pound. ing, he pays higher for chemicals for spraying, he pays more for his machinery, for these also are mo- nopolized. But the market masters pay no more for apples, for the apple market also is in the hands of monopoly—monopoly in effect if not in actuality. There is an insistent propaganda in Washington now for co-operation as a means of combating the political organization of the farmers. To those back in North Dakota and Minnesota who remember the Equity fight, the assertion that the old-gang newspapers are preaching agricultural co-operation may sound ridiculous, butit is a fact. Co-operation has been tried. My friend from Klickitat county has tried it. A local growers’ asso-~ ciation was formed. There are many growers’ as- sociations - throughout the state of Washington. Z_Each of these co-operative enterprises is employ- ing a high-salaried sales manager and perhaps other salesmen. But they are not getting anywhere. The man from Klickitat, who was one of the mov- ing spirits in his organization, was perhaps the first to withdraw, and a few years later saw the whole organization collapse. It collapsed because co-operatives have been found to be futile. The individual fruit raiser sells his fruit. Unless he wishes to market it himself, as did the grower who sold his prod- uce at retail, he must dispose of it through brokers or commission men. SHIPPERS® ASSOCIATION NOT FARMERS’ BODY .The salesman for the growers sells the fruit of the association whom he represents. To whom? To these same commission men and frixlit brokers, for there is no other place to sell. : _The matter of price is fixed at the begin- ning of the season by the Fruit Shippers’ as- sociation. The name would indicate, then, that the shippers, or growers, had something to say about the price of their fruit. But you are not misled.~ You who live on the farms know this would be against the ruies of the game, and the growers who had the temerity to fix their own prices would be radicals of the worst sort. But the Fruit Ship- pers’ association members ‘are not Bolsheviki. = . SE S They are not shippers at all. They are the buyers of fruit, the sommission men and the brokers. : Surely, there may be a farmer or two, but without an effective voice. And who controls these brokers and commission men? It is the pack- ers again, who have their own brokerages and commission houses in connection with the American ‘Fruit Growers, Inc., a body formed something more than a year ago, with Charles J. Brand, former head of the bureau of markets in the de- " partment of agriculture, as man- ; (Continued on page 14)