The Nonpartisan Leader Newspaper, January 12, 1920, Page 4

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

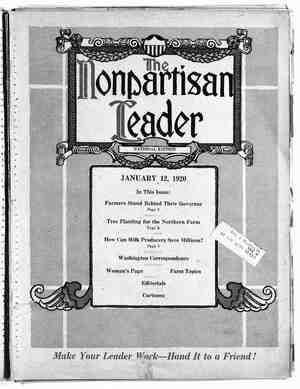

Tree Plantmg for the Northern Farm Serves Triple Purpose of Protection From Snow, Cold and Drouth and - L QUARTER of a century ago Kansas and Nebraska had suc- cessions of drouth years and complete crop failures, worse than those now experienced by the Dakotas and Montana. Twelve or 15 years ago hot, dry winds used to sweep up from the south into Minnesota, killing everything before them. But now, year after year, Kansas produces wheat and corn crops without anything approach- ing a complete failure and the hot south winds no longer trouble Minnesota farmers as they did. Be- sides that, any old timer will tell you that we don’t have the bitter cold winters that they used to have in the ’80s and ’90s. What is the explanation of this change of cli- mate over a whole section of a continent? A good many reasons might be given. One of the most likely can be told in just ’ two words: Tree planting. One reason why the win- ter cold is so severe through the Dakotas Iis that there are no moun- tains, hills or forests to the north to stop the wind that rushes down, across the flat prairie, straight from the North pole. Ev- ery one knows that 30 de- grees below zero, on a still day, is not so uncomfort- able as zero weather with a 30-mile wind. Why the hot, dry south winds of summer are so destructive is pointed out by State Forester Cox of Minnesota. “It is a well-known rule of physics,” says Cox, “that the evaporating pow- er of wind increases as the square of its velocity. That is, a 20-mile wind will take moisture out of the ground four times as fast as a 10-mile wind. So whenever, by tree plant- ing, the farmer can cut the wind velocity over his fields in half, he is cutting down the evaporation to one-fourth of what it was.” THREE KINDS OF TREE PLANTING Arthur F. Oppel, silvi- culturist of the Minnesota forestry department, a ‘resident of Murray county, in southwestern Minneso- ta, where the hot winds used to kill crops regular- ly, is convinced that the tree_planting of the last dozen years is largely re- spousible for the fact that the hot south winds don’t blow to the extent that they did. But whether tree planting, to the extent that it has been carried on, will have a general influence on climate or not, there is no doubt whatever that trees planted correctly as windbreaks and snow- sheds have a wonderful effect in protecting the property of the individual farmer. In southern Minnesota 1911 was the last drouth year. One narrow grove of young trees, only 25 feet high, saved the corn crop of one Watonwan county farmer when every other field in the district was ruined. Tests in Nebraska, during ordinary years, have shown 81-bushel yields from a field pro- railroad right of way. close to the buildings. tected by a windbreak, as compared with a 42-bush- el yield from-an adjoining field not protected. The corn directly shaded by the trees did not do so well as that a dozen rods away, but even the few rows of shaded corn did as well as the corn in the unprotected fields. There are three kinds of tree planting that should be considered from the standpoint of the farmer. belts. A grove is intended primarily for the protection of houses and other farm buildings from winter winds and snowdrifts. Cutting down the force of the cold wind not only makes living conditions more bearable for humans but makes stock raising conditions better. Wood lots are suitable for farmers who have the land to spare. Many farmers are finding it good economy to raise their own fenceposts as well as their own cordwood. In this connection it is worth remembering that a soft wood like willow, dipped in creosote, makes as good a fencepost as could be desired. It is also worth remembering that on almost every farm there is waste land of one kind or another, that may be suitable for tim- ber production, if for nothing else. In many of the states individual farmers, who have gone in for production of cord- wood and fenceposts as a commercial proposition, have found that they have been able to make as much, per acre, as they could from or- dinary farm crops. These are groves, wood lots ‘and shelter Proper tree planting will protect either farm homes or a railroad from drifts and cold. The picture at the upper left shows unprotected farm buildings and the picture at the lower left an unprotected The farm buildings at the lower right are protected by a grove, but it is too In winter the snow will bank between the buildings and the trees. The picture just above this shows a railroad right of way properly protected; the shelter belt at the left allows some snow to drift through, but it does not get as far as the track, 100 feet from the trees. The shelter belt at the right of the picture is made up of deciduous and coniferous trees niixed and stops almost all the snow. However, the question of whether commercial wood growing will pay or not is one that each individual must decide for himself. Shelter belts are intended prlmarlly for the pro- tection of crops from high winds, hot winds, cold winds and drifting snow. A variety of trees can be used, especially in states like Minnesota and Wisconsin. In the prairie states the number of varieties suitable for planting is somewhat small- er, but chance for considerable choice is still left. The trees in the three following groups can be - grown almost anywhere in the West and Northwest. Fast-growing dec1duous——W1]lows, poplars and cottonwood, box elder. Slow-growing deciduous—Elm, ash, hackberry. Coniferous—White spruce, jack pine, Norway, Scoteh and Austrian pines. A well-planned shelter belt or grove should ful- fill these requirements: : It should be at least four rods wide. - . PAGE FOUR . Provides Ample Wood Supply It should be 100 feet away from the building or fields to be protected, if it is planned as a protec- tion against snow as well as wind. It should be planted at right angles te the course of the prevailing winds from which protection is sought. It should be made up of a mixture of trees, chosen from each of the three groups listed above. The reason for the last-named rule is this: The fast-growing trees, like the willows and poplars, are needed to protect the trees of slower growth. As the slower trees get their growth the fasi-grow- ing trees can be cut out and used for firewood or other farm purposes. A mixture of the slower- growing deciduous trees with the coniferous trees gives a combination screen that will shut out the wind and snow, both above and below, much better than the trees of any single variety. PLANT TREES 100 FEET . DISTANT FROM BUILDINGS No shelter belt or grove that can be grown in ° the prairie states will prevent snow from drifting through to some extent. But the speed of the wind will be so much reduced that the snow will be piled up a few yards in front of the trees instead of blowing on to bank up around the house and other farm buildings. For this reason it is important that the grove or shelter belt be 100 feet away from the buildings to be protected. A shelter belt, four or five rods wide, is not only much better protection than a windbreak formed by a single line of trees, but- also is easier to get started. The trees will protect each other during their growth. And if the varieties of trees ‘are mixed properly, it will af- ford protection from the start and will last practi- cally indefinitely. It is important to plan the location of the shelter belt in relation to the points of the compass. This will depend upon the direction of the prevailing dangerous winds of the lo- cality. In Minnesota and Wisconsin the northwest winter wind and the south- west summer wind are to be guarded against. A shelter belt or grove to the west of the buildings or fields to be protected will guard against both these winds. Through Kansas and Nebraska, however, the hot summer winds gener- ally come direct from the south. Through the inter- mountain states of Mon- tana and Idaho an early summer wind from the northeast and the early spring chinook from the northwest are to be watched. In setting out trees a dull, cloudy day is prefer- able. Earth packed around the roots should be moist, but not muddy, and should not be too tight. After the young trees are set out they should be cultivated during the first three or four years, to keep down weeds and keep the soil open. Farmers of the prairie states interested in tree planting should write the United States experi- mental station, Mandan, N. D., for advice. The Minnesota state forestry department, St. Paul, Minn.,, is well equipped with information pertammg to that state, which also would apply to Wisconsin. The following pamphlets can be secured upon " application to the sources named: “‘Forest Planting on the Northern Prairies,” Circular 145, Forest Service, United States Government Printing Qffice, Washmgton. D. C. Séxccesaful Tree Planting,” Department of Interior, Otta- wa, Can, “Tree Planting for Shelter in Minnesota,” Forestry De- partment, State Capltnl St. Paul, Minn.