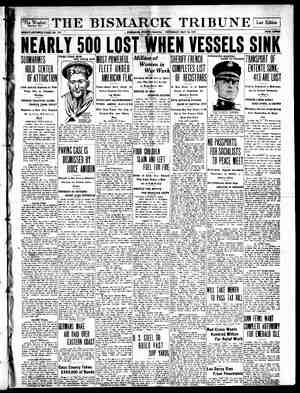

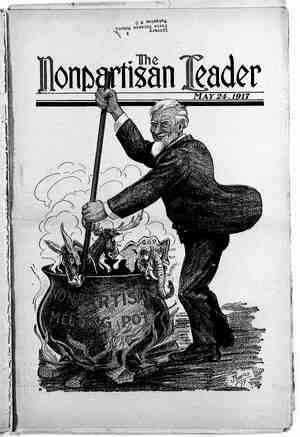

The Nonpartisan Leader Newspaper, May 24, 1917, Page 8

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

; Cold Storage Trust Outlines Plan Borrow $2 Per Case Now to Speculate in Eggs, Say the Wise, and Make the Consumers Pay Next Winter TORAGE eggs will retail at 50 cents a dozen this coming winter, the “bulls” among the egg barons predict. Farm® ers throughout the Northwest are supplying many of these eggs now. They are getting about 25 cents a dozen for them. Who gets the other 25 cents? That is quite a story. No one admits getting more than a few cents. The country grocer who buys the eggs from the farmer is sure-he gets no more than a fair profit, the produce man who buys from the grocer is positive he is en- titled to the margin he takes for hand- ling and grading, the jobber who puts the eggs in cold storage tells about the expense he is put to in keeping them there until there is a demand, and the retailer certainly has to have his bit out of the transaction. It actually works out something like this: The farmer takes his eggs to the country store. They are just “eggs” then. He gets, generally, somewhere around 25 cents a dozen for them and, more often than not, he has to take it out in trade. The grocer, when he has several cases, ships them to the pro- duce man at Mandan or Bismarck or Fargo, and gets about 30 cents. There the eggs are graded. They are ‘“cur- rent receipts” instead of just eggs at this stage of the game. Oversized and undersized eggs, eggs with thin shells, eggs with dirty shells and any that under the candling test show deterior- ation are taken out. The eggs that pass the test are repacked in new cases and shipped to a large-center, Minneapolis, St. Paul or Chicago, for storage. They are ‘“storage pack” now and are worth 35 cents a dozen or a little better. At this point the eggs go into the “cooler,” worth somewhere between 35 cents and 40 cents a dozen. The only ones who have gotten their “bit” out of the dozen eggs thus far, besides the farmer who raised and fed the hen that laid them, are the country grocer and the produce man. But several other parties make their appearance now. The jobber, who generally. owns the eggs, has to borrow money from his friend, the banker, to carry them over until there will be a demand from the US FARMERS PIDN'T GET, THEM PRICES ‘‘Why don’t you tell something about eggs and poultry?’’ a read- er asked the editor of The Nonpartisan Leader the other day. ‘‘The farmers’ losses on his chickens amount to more than his losses on his wheat.”’ This is hard to believe but it is true. The annual egg and poultry crop of the United States is worth as much as the annual wheat crop, somewhere between $600,000,000 and $700,000,000 a year. The loss to the producer and consumer is much greater than in the case of wheat, because the ‘‘spread’’ between the originall price to the farmer and the final price to the user is greater than in the case of any other major food product. The successive prof- its that the middlemen take out in the egg business make the mid- dlemen in the grain business look like pikers in comparison, consumer. He also has to pay storage charges to the refrigerator companies. Also, the insurance company comes forward for its piece of money. So if the dozen eggs go into storage costing 35 cents, they have to come out and be sold for 40 cents, or if they go in at 40 cents, they will have to be sold for 45. cents when they come out, if the jobber is to make a profit. And then sometime next fall or win- ter the eggs go to the retailer, gener- ally to the grocery store again, and another five cents.will be added to the cost. This will make the price of the dozen eggs to the consumer 45 cents this next winter if the ‘bears” of the egg market are successful in holding prices down, or 50 cents if the bhulls have their way. NICKEL BY NICKEL THE EGG PRICE CLIMBS It is like the story of the down Bast farmer who went to Coney Island for the first time. When he got home he told his friends about it, around the stove at the village grocery. “It was interestin’ but terribul ex- pensive,” he said. “Every time I turned around, bang went a nickel.” So it is with the dozen eggs. Every time the dozen eggs is turned over, bang goes a nickel onto the original price. But none of these extra nickels get back to the farmer. Some of the produce men will say that the farmer gets more than- 25 cents. The produce men are advertis- ing to pay $9 a case for eggs'in new cases, which is 30 cents a dozen. It is quite true that the farmer can get this price by shipping or bringing his eggs to the produce companies in any of the larger towns or small cities scattered through the Northwest. It is also true that if the farmer could grade these eggs and ship them by th'e case to Chicago, he would get 37 cents a dozen for them. But he can not ship them to Chicago, and in many cases he can not ship them conveniently to “Speculation and speculation alone is the cause of the the United States steps in and halts speculation, butte summer,” said F. C. Coughlan of New York. - than they ever were in New York,” said H. A Eggs may be displayed in jewelers windows, like precious stones, before next winter is over, in spite of the fact that the farmer cannot make a profit on the price he gets. agement’ has been applied to almost every big business today, except the biggest business of all, that of getting food from the producer to : the consumer. Experts say that eventually the Northwest must produce a major part of the egg supply of the nation. Grain production and egg pro- duction naturally go together. Butthe farmer today cannot make a profit from his poultry flock. This article and the one which follows tell why and suggest a remedy. : Fargo or Bismarck or Aberdeen. Gen- erally the country grocery gets them at around 25 cents on a barter ar- rangement, as primitive a means of trade as was used when the first set- tlers came to America and had to deal with the Indians. Going to the other extreme, there are plenty of farmers who are selling their eggs at even less than 25 cents. One Fargo buyer told the writer that he had bought a case of fresh eggs re- cently for $6 or 20 cents a dozen. The farmer was glad to get the cash, rather than to be forced to take it out in trade at the store. But generally, 25 cents a dozen to the farmer is a fair average for this year. \ The storage men have their own arguments, too. The writer was talk- ing to one of them the other day: “Take so-and-so,” said the storage man. - “He made $100,000 -on storage eggs last year, that's true. But year _before that he lost practically every- thing he had and nearly went to the “Scientific man- wall because he guessed wrong on the price of eggs.” BANKS GAMBLE GLADLY IN EGGS “This cold storage business is an open game. Anybody can get into it. All you have to have is $2 a case to pay on your eggs, the banks will loan you the rest, and enough to pay your " storage and insurance.” That is true, as far as it goes. But not everybody has $2 a case to pay on anywhere from 1000 to 100,000 cases. And what kind of a welcome do you suppose ‘a .farmer, with a first mort- gage on his place, would get if he went to his banker and asked for a further loan to use in egg gambling? The storage men are sincere in look- ing at it as an “open game.” Anybody who has the money can play, but the stakes are too large for a piker. How much the storage men look upon the business as a “game” is indicated by this quotation from the last issue of A EIGHT present high prices in many food stuffs. If ’ r and eggs will be comparatively cheap this “Food gambling conditions in Chicago are rottener . Emerson, food investigator for state of New York. the Egg Reporter, the official journal of the trade: “Many of our large receivers claim that 40-cent eggs in the coolers will be good stock, 45 cents to take out, 50 cents at retail, so you see that the egg proposition is already mapped -out and all we will have to do is pay our nmoney and help the egg market.” Easy, isn't it; just “pay our money and help the market,” everybody get in and boost prices and divide up after- ward. Only it makes a pretty stiff game of it; one that puts Monte Carlo in the penny ante class. In the egg business, this year, the sky is the limit with a vengeance. ¢ It is true, however, that the farmer this year is getting a higher price for his eggs per dozen, than he did last vear. The average price to the farmer at the produce house, ranges around 10 cents a dozen more than the price a year ago. In some instances buyers are paying practically double old rates. But notice, the farmer is getting more per dozen. His actual total receipts in egg money are little if any larger than a year ago. And if the farmer is ac- tually making any profits at all on hig poultry, above the cost of feed, he is extremely lucky or an extraordinary manager, for with feed at present prices there is no money for the average man in the poultry business today. POULTRY LOSSES DRIVE FARMERS OUT OF BUSINESS The reason that in the face of in- creased prices for eggs and a real egg shortage, the farmers’ actual receipts for eggs are no greater is that in the last year the American farmer has been gradually going out of the poultry bus- iness. Even Feed D wheat is too ex- pensive to feed to chickens. The farm- er in almost every section has been gradually kKilling off his flock and sell- ing it. The high price of feed and rea- sonably good prices for poultry have encouraged this. So it is that the buyers in every sec- tion of the United States are reporting back to their principals that eggs are scarce. In the face of a world-wide demand for more food, the Great- Am- erican Hen will be unable to do her share, because there is not enough of her left. That is why the farmers are getting 10 cents more a dozen this year, that is why there are only half as many eggs in storage as there usu- ally are at this season, and that is why the egg trade predicts 50-cent storage eggs this winter, with fresh eggs prob- ably entirely-out of sight. The egg situation today does not look very promising either for the farmer, who gets only 25 cents for an article that will be handled on to the consum- er for 50 cents, or to the consumer, who will be compelled to pay 50 cents for what cost only 25 cents to produce. The situation reminds one of that old wheeze about the hard boiled egg: “It can’t be beat.” But there is another egg story that ; (Continued on page 13)