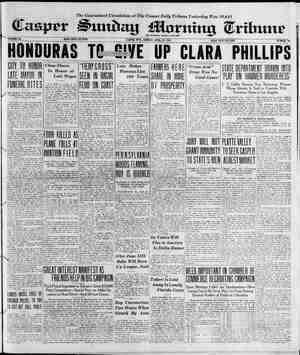

Evening Star Newspaper, April 22, 1923, Page 76

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

He Dealt 7 Fancies, But Paid #m Cold, Hard Cash. His Own Barthly Oblgatrons of Honor HERE was once a bov who picked the wrong parents; and they rinsed the spontaneity out of him, and they starched ®im with countless forms and inhibi- tions. He was rigidly, tensely repressed, But this repression partook of some- thing of the quality of a steel spring. Siever yet released, but always ready and waiting. And in his heart there ! were three renegade ambitions: One of them was to play on the Harvard oot ball team; one was to compose musical comedies which would make him rich; and the third was eventu- ally to see the world, and, in par-- ticular, France. In his seventeenth year, however, Nelson's father's business failed, al- most overnight, and this disaster, vaturally enough, affected Nelson's whole life; but for the moment it ‘meant primarily that he was to take no more music lessons, and that if he were to go to college at all he should have to work his way through. He did it, and he took honors, there was no time to play foot ball. and there was no time to make friends. Just as he graduated his father died, so Nelson went to work at the note desk of the Messina National Bank. He had u mother, two eisters and a younger brother to support. Furthermore, his father's debts were hovering over his pride. He had never understood his father, but he had been proud of him; and now he was bitterly jealous of his faith and credit, “If T live long enough.” he said to the cashier of the bank. ‘I'm go- ing to pay off every cent of it." The cashier put his hand on Nel- son’s shoulder. “You don't owe us anything. And you couldn't pay off the whole wad of it in a hundred vears. You got more'n you can do to take care of your folks” And this was genuinely stoic, because the cashier had personally loaned the elder Nelson four thousand dollars ‘without security. “That's all right” said Nelson, tight-lipped. “You just give me +ime, Mr. Miller—you just give me time.” The cashier smiled indulgently. “Well, then, I tell you what you do, Eddie. Pay me last. Because I was pretty close to being your dad's Dbest friend. . . . EE ! twenty-three, Nelson had put on a coating of responsibility which resisted all weathers. Neither of his sisters had married. and his mother observed mournfully that Nelson didn't seem to be getting aiong very well. So that Nelson shut nis lips a little tighter and worked a little harder, and, in consequence. went trom the note desk to the re- celving teller's window and thence to the paying teller's: and when Mr. Miller resigned to go into business for himself Nelson became cashier. At this stage @ great trust company in New York happened to hear of Lim, and Nelson was beckoned down into Wall street. When he was thirty-seven Nelson Wa: second vice president of the Gibraitar Trust Company, and he had cleared his patronymic of every penny which had been marked against it. fund which guaranteed his mother and his two actdulous sisters for life. e had put his brother through Tech, and bought him a partnership in a promising firm of engineers. And then Nelson was independent He was an important man in & vast tnstitution, and outside of it: and outside of its clientele he hadn't a 1ritnd in the world. And a month after he had written the last check to his father's memory the president of the Gibraltar Trust sald to him: “Ed, you're not looking so awfully fit. ... Now the Parls branch needs a little supervision, and vou could give it an hour or two a day, and loaf the rest of the time, for about four months; and then put in the next eight months just bumming around Europe. 8o I'm going to send You over for a vear.” ok ox o x S Nelson passed over the last cleat of the gangplank he had a faint flutter which was a decade and a half overdue. As he unpacked he ‘was suddenly aware of himself in a small mirror; and he beamed, mod- erately, at his own image, and forgot ghat he was the coldest proposition in Wall street, and that his heir was graying about the temples. France, which for several years had regis- tered upon him only as a country in which the Gibraltar Trust had a branch office, suddenly resumed at least a faint glimmer of its former 1llusiveness. ‘The ship was a one-class steamer of the French line; it wasn't fashion- able, but it was fast and it was com- fortable, and furthermore, in June, no other booking had been available. At the first view of the promenade deck the impression he gathered was that all the world, except himself, was twenty, and gloriously irrespon- eible. For the next two days he con- tinued to fluctuate between opposite moods. At times he was imagina- tively stirred by what was ahead of him, and during such moments as these he was vaguely wistful and lonely, when he watched the skylark- ing; but at other times, when habit clanked the shackles, he told himself that young people were an infernal nuisance. The third day, which was sweep- ingly blue and golden, brought him out of his berth with a bound. It was not yet 8 o'clock when he had breakfasted and was out on deck with s good cigar and a good conscience. He was just outside the salon, and he went in. The salon was utterly deserted, and in the farther corner tnere wae a piano. Nelson had been playing very quiet- 1y for perhaps fifteen minutes when he broke oft with a great start, and half rose from the bench. A girl w standing in the doorway, gazing at him. She was a girl whom he had already noticed, on deck, and distantly ad- mired. She had a warm vividness which set her aside as an individual. Afentally, he had compared her with a fire-opal. “Oh, I beg your pardon,” she said— and her voice was quite as boyish as her manner. “I beg your pardon. I didn't mean to interrupt you—but would you mind telling me what that was you were just playing?” “Why,” said Nelson, “it's & thing called *The Seller of Dreams. A’h- regarded her he was increas- B but| He had set up & trust| ingly conscious of his age. At close| range she seemed to be twenty-two or twenty-three, but her eyes and her | attitude both belonged to seventeen.| And her eyes were lovely. “Do you know who wrote it?" Nelson smiled at her—a smile which, because it was defensive, was almost patronizing. “I wrote it my- sel. She looked at him, looked at the plano, looked back at Nelson and shook her head. “No—truly. Please tell me.” “What?" said Nelson. believe me?* “Why, of course not. Not unless your name's Rachmaninoff or Nevin or Kreisler, and if ftis ® * " Her s had little dancing lights in them. 0, please—I really want to know who did it.” Tha's my story.” said Nelson, “and I'm going to stick to it. Espectally now you've committed yourself. She gave him the glance of a child Wwho has been teased one degrec too far; hesitated, turned .toward the door. Well,” she said, “I like it—any- way. She went out, and Nelson laughed, absently, under his breath. He couldn’t blame her; for he was said to be the coldest proposition in Wall street, his fingers were Stiff from lack of practice, and he had written tkat particular melody when he was eighteen. * * ¢ “Don’t you o ok ¥ T was another day before he met her formally. He had been sitting n the smoking room, reading, when some one coughed for his attention. It was a tall and bulky and extremely handsome young man who was the magnetic pole of the boat, and espe- cially attractive to the fire opal. “Sorry to Interrupt your devotioni said this young man genially, “but are you on any tug-of-war team yet?"’ “Tug-of-war!" sald Nelson. The young man grinned. “Then I guess you're on mine. That's all right, isn't 1t?” Nelson put down his book. “To tell the truth, I'm not even sure I can| pull my own weight. So perhaps you'd better leave me out of it | The young man shook his head| knowingly. “You've got a peach of a| build, and we need you. And, be-| sides, I was tipped off you're a kid-| der. anyway.” Nelson surveyed him blandly. “Far be it from me to question your infor- | mation, but I'm curious to know just where you got it.” | The young man laughed. “That's| all right. That's your reputation.| Don’t you want to come around and| meet some of our crowd? My name's Dexter.” | Nelson got up and went. | He met, first, a prim and retiring | chaperon, then seven boarding school | flappers and half.a dozen young men, | and finally he found himself shaking| hands with the fire opal. ! “So glad to meet you, Mr. Rubin-| stein,” she said. “I've heard your| ‘Melody in F" 80 often—on the phono- graph.” Yesterday he had thought her| charming; today he thought her ador- | able. “I understand you've been libel- ing me” he sald. “That's a serlous offense. And T ought to warn you| that, no matter how timid I look, I'm| vindictive. | She laughed infectiously. “Ana what else do you do in your spare time?” she inquired, “besides compose masterpleces?” Nelson had an inspiration. “Well” he said, “I walk. In fact, you might almost say that walking is my chief- est acoomplishment. * * * a demonstration interest you?" “Why,” she said, uncertainly, a sort of halt-way understanding | with Freddle Dexter. ¢ * * “I'll fight it out with Freddie Dex- | ter if necessary.” Her eyes were provocative. “Be | careful. Freddie was on the Harvard foot ball team * * Stil, I sup- pose you're a champion boxer among other things, aren't you? So ver-| satile.” “You never heard of Jack Twin Sulllvan, did you? * * * Really? Well, I've stayed eight rounds with | him. That was when I was in col- lege” ‘Oh, come on, and walk,” she said. “You're much more interesting than Freddie, anyhow. Freddle's so truth- T had | * ¥ % % ful” N OST women thought that he was laughing at them; and, at first, the fire opal was no exception. And what else could she think? She asked him a few questions about himself—where he lived, what he did, why he was coming abroad—and in every response there was the flavor of repartee, instead of straightfor- wardness. She laughed, obligingly, but she was more than a little piqued, because it seemed to her that Nelson was discounting himself. He was good-looking, well poised, metropoli- tan; and he told her, with appropriate epigrams, that he hadn't danced for nineteen years, that he didn't play bridge, that he couldn’t distinguish between one golf club and another. He denied that he rode horses, read novels, went to base ball games, or frequented the opera. He added, gratuitously, that he didn’t crochet, knit, tat or embroider, either. How could she know that, although he wi & master of men, he was woefully shy among women? How could she know that in telling her the truth he was also trying to cover up the sore spots in his blography? Her eyes puszled him. “Of course you know perfectly well,” she said, don't belleve a single word you've told me. And of course you didn't expect me to. Good-bye—only next time won't you please change your act? Enough is enough.” As he went below he was slightly irritable. Here was a slip of a girl who took him for a comic, even where he told her nothing but sea-level facts. It made Nelson feel very un- stable; and instability is one of the attributes of youth. Furthermorc:, Freddie Dexter had asked him to pull on a tug-of-war team. Evidently, he didn't look as senile as he had imagined. That night the air was sweet and fresh, and the sea was velvet-calm, 8o that presently thers was a con- certed rush to what Freddie Dexter called the mezsanine deck, high in the bow. y 3 In a very secluded angle of the rail there were two empty chairs: Nelson dropped into one of them and smoked, meditatively. Tru people were ¥ | body | tor you | itate. | ever know. that whatever you did was quite all THE SUNDAY STAR, 'WASHINGTON, D C., APRIL 22 )| i “THERE ARE ALL THE TREASURES OF THE WORLD SPREAD OUT FOR YOU. SELLER OF DREAMS.” 1923—PART & THE SELLER OF DREAMS “Did you have to work as hard as that? All this time? Just to get along and pay bills? Or did you want to?" No: I didn’t want to. pay bills.” “But you went to college?” “Yes; 1 worked my way through.” “And you dldn’t have any fun the: efther?” “Hardly.” “Then if this is all you've ever had,” she sald, “and you walited so long for it, why did you make it 8o hard for yourself? And when I came to you that night, why couldn’t you have talked to me then?” He shook his head. “I don’t know.” “What would you do—Iif you could?” “What would I do?” He was smil- ing out at the sea. “Why, I suppose I'd rent an ancestral estate, some- It was to— HE'S AN OLD BANDIT, OF COURSE, BUT SPILL HE'S A young—young—young. Nelson sud-[ltked it yesterday. But still You he again succeeded in getting her to]wmm near Paris, and radlate from denly filled with a curious hot resent- ment against the very qualities he longed for—youth, and gay-hearted- ness, and spontaneity. PR ““ IND if I sit down a second?” .\[ Nelson scarcely turned his head. “Of course not.”" | She curled up in the other chair. and settled herself into comfort. Nel- son went on smoking. There was a silence. “You're an awfully she said, eventually. “In what wa) She inclined a degree or two toward him. “Oh, it isn’t only the way vou act; it's in your eves, and the way you talk. You talk off the top of your mind all the time—just so no- can possibly tell what you're thinking about. Yesterday morning | and then again today you made me so provoked 1 wanted to throw.some- thing at you—but now I'm just sorry funny man,” Nelson raised his head me She nodded. “Just as sorry as I can be. Because 1 don't think you'd | ever behave like that if there weren't some good reason for it. You're not| a humorist, really. What is it: just | “Sorry for ; | | that you don't like people?” He continued to smoke, and to med- | “No, that fsn't it . . . but why | should you bother?” She hesitated. “T don’t know if I} | can even trust you not to be facetious | he said. about thie. ... Well, anyway—ever| Then it fell right into my | And | pected it lap. Right out of a clear sky. |now I'm going to have ten weeks— | ten of the” most wonderful weeks I'll She drew a long breath: her eyes were shining. “I'm the luck- lest person on the whole boat. And 1t isn’t fair for me to be 8o happy all alone: I wanted to share it with some- body. And nobody else seemed to— need any of my share. And vester- day morning, down in the salon, you were playing something that fitted so exactly everything I was thinking and feeling, and you had such a queer look on your face . . . . well, that be- gan it. And then you squelched me. And then today you did it again, and I loathed you—until I'd had time to think about it. And then I watched = The only sincere minute you've spent on this boat was when you dldn't know I was looking at you! I'm trying to help you.” * x ok E stared at her for a long half- minute. “My guess,” said Nelson, irrelevantly, “Is that you come from & small city somewhere and you've lived in the same place all your life. Isn't that so? 'You see, girls like you,” he went on, “don’t grow up very often in big cities. They go there afterward sometimes, but they don't grow up there—not often. . . You haven't been snubbed very much,” he sald thoughtfully, “and you've always been surrounded by people who loved | you and trusted you and believed it. You right, simply because you did Isn't that true? I thought so. show it.” 'You mean I'm too personal? 1 supposg I am. I suppose I never ought to have been interested at all. I'm sorry.’ 5 “No, that isn't it at all” He cleared his throat. “I meant that it's rather—startling—to have any- body so—direct. It's—refreshing.” His voice, however, was badly reg- ulated—the old, defensive note of rafllery had crept back into it “You said something about wanting #0 much to come abroad. Well, you're not even In my oclass. I've been waiting and working and plan- ning for this trip for almost as many years as you are old. ou take that thing you liked yesterday—T'll tell you the idea. .. . Did you ever build up in your mind & picture of what Cairo must be like, or Alexandria or Tunis?... You 80 out of that smashing sunlight into & shadow that pretty nearly blinds you—into & bazaar, a shop—and there are all the treasures of the world spread out before vou, and over it all, bowing and salaaming and rubbing his hands, and as pioc- turesque a8 can be. Oh, he's an old bandit, of course, but still, he's the seller of dreams—that is, 1f you think of it the way I do, and it takes hold of you. “I like the picture,” she saM. ‘T { | going haven't answered a single thing I asked you. Let's begin at the begin- | ning. Who wrote ft?° H “Why 1 di4" said Nelson, “nine- teen years ago. You didn't think I'd take that back, did you?” ! After u pause she laughed. “When you were, say, twelve? Your parents must have been awfully proud of Fong m nearly forty. And my parents never even heard it; they wouldn't have been Interested.” She stirred in her chair. minute T honestly thought to be serious. goat?” He was alone in the secluded angle by the rail. He stared at the whiten- ing water and tried to be exhilarated because he was going to Franee. “Gosh!" said Nelson, halt aloud.| “She didn't even believe I'm thirty- seven!” * o HE next day it was almost tea time when he discovered her, sit- ting sollitary and subdued, on the wrong side of the boat in somebody else’s deck chair. He had no possible reason to know then that Freddie Dexter had been proposing to her and she had asked for a moratorium; | he merely saw his opportunity, and | took 1t. “I've been looking for you ail day,” | “I wanted to explain things | to you and tell you how much | Would | since T was a little girl I've been |1 appreciate your bothering about | | crazy to see Europe, and I never ex- |m, She shook her head and smiled me- | chanicaily. It's lots better mot to explain things. So often, it just| makes everything worse. It's all| right. I've thought it over, and there simply lsn't any use in trying to| make people into what they don't| want to be. It's so much easier to | take them at their own valuation. So | sit down and tell me all about your two Rolls-Royces, and what a bright boy you were at school.” It fascinated him, perversely, to tell | her the truth, once more, in the most | literal form, and to see how she dis- believed him. “I've ‘made a fearfully bad impres- sion on you, haven't 17" he asked. “You've worked hard enough for it.” “Well—if it isn't too late—tell me how you want me to behave, and I'll behave that way.” “I want you to be yourself. That's all. “But I've been myself all the time.” She turned her face away from him. “Then go on. Keep it up. Go ahead being a comedian. Maybe that's the best thing you could do.” “But—why?" She turned swiftly back. “If I knew,” she said, “maybe I could tell | you why I like you in spite of your- self. Maybe I could tell you why I like you in spite of almost every word you've said to me. But I don’t know. All I know is . that you amuse me . and it's time for tea. Do you want to get some for me K X ¥ NE evening Nelson talked to her about travel and other serious things. And, toward the end, he had an unexpected reward, for she said to him: *“I'm awfully glad we had this talk. I'm glad to know you can be sincere about something. I ilke you lots better now. Won't you please keep on like that?” “Why—T'1l do my best,” lamely. “And by the way—' “Ye “About that “other night—I Jjust want you to know I think it was per- fectly—bully of yo “Oh!" “Nobody ever took that much trou- ble about me—in all my life.” “Nobody 7" he said, She put her hand on his arm. “Why if that’s true—then that's what's the matter with you—isn't {t?" And that was all there was to it; but a few minutes later, when they were drafted into the inevitable chorus she didn't let herself be switched aside by Freddie Dexter. She sat by Nelson, and both men were keenly aware of it. Nelson realized that he had long since stopped fretting for the Paris: he considered the Rochambeau the finest ship afloat. It lacked no single detall of perfection; it contained everything In the world he could re- motely think of wanting. Her name was Alice. On the evening of the tug-of-war {in my mind, anyway. himself, for an hour. Suddenly he said to her: “When- ever I'm with you I have the most extraordinary sort of feeling that you know everything that's going on Every now and then I wake up and find I've only been thinking, when I thought I was talking.” “Then T wish you'd really tell me about yourself.” “I've told you a good deal already. Suppose I swore It was eévery word true.” There was a long pause. “You couldn’t hurt my feelings as much as that, could you? . . . Because tonight, I'm golng to believe you. What do you do in New York?" “Why. I work in a bank. I've got something to do with foreign ex- change.” “You're not coming over just to bat around, then?" “No; on business.” And you've never been abroad be- fores I've hever been anywhere before.” But it wasn't true about your not playing any games, or not having any fun, or anything, was {t2* that was gospel Lisien,World! D& N an old Spanish story there are related the amazing wanderings of a certain student and an agreeable “devil on two sticks.” In return for favors rendered, the devil promised the student that |he would take him iIn & nighttime ight over the houses of the great city and reveal to him what went on under the divers roofs. It was done. Over the roofs they went—pompou turreted roofs; mean shabby roofs those which housed the great and saintly, and the poor and lowly. To the student's curious eyes all secrets were uncovered— But, quaintly enough, whether the roof were mean or magnificent, only one thought was found to rule the hearts of those beneath—Romance. The age or station of the house owner made no difference. Romance invari- ably dominated those hours when a man can choose to be himself. It's an old story but it is as true in America today as’it was in Spain when students and devils cavorted together In such friendly fashion. from every head you pass and peer into the most treasured secret hid- den within that head and heart, what would you find? Romance. Shy, flut- tering romance —bold, lawless ro- mance—but always some sort of romance, romancing away for all it was worth. And always throned in the midst of the romance, you would find the ideal mate, & creature usually £0 marvelous that even the devil on two sticks would have been hard put to classity it. * % k% HE other day the following letter came to me. As surely as though that accommodating fiend had lifted the roof, I saw the story of this house pf life revealed. The wistful- ness of a woman who has passed her youth, the sorry comparison of some mere man with the hero enshrined in her dreams. It's such a human little letter. So I'm glving it to you today, just as it came to me: “Dear Elsie Robinson: “As 1 read your talks on love and marriage I think so often of my ideal husband. I+ suppose other women thing of that, too. I'm going to write down my list of qualifications, for perhaps they may prove interesting. “First of all, a man to be a good husband must be a Christian no mat- ter what his occupation Is. “Second, he must be a teetotaler, have clean personal habits and not use tobacco in any form. Third, he should be a well read man. The man who does not care for good books or magazines would not appeal to me. “Fourth, in disposition he should have humor, a kind, loving, sympa- thetic nature, and not be either too lazy or ambitious. There are some men so busy making money that they have no time to help rear their chil- dren or give their wives attentioff. A man should enjoy taking his wife out in public, to church, lectures, to anything that is & diversion to him. “He must be neat but not a fop. “He must be ingelligent and wide- | ] you could by eome magic 1ift the roof | {it. Without any regular plans; just |drifting. Don't you think that would | be pleasant?” | “It's exactly what I'd do, myself.” {She drew a long breath. “That's the one idea we've always had in com- | mon.” Nelson stopped smiling. “Of course, | there’d have to be a princess . | that's understood. You come nearer | to being the princess than anybody I | ever met.” It was many seconds before she an- swered, and then her voice was very | Tow. | ‘Te TI've known it for two days . . . But why do you like me? Oh, it's all right, I wanted you to |- . . but why do you? We're 50 | terribly different . . . | His heart and his mind were full of | things he wanted to say to her, but for the life of him he couldn't get them out. Therefore: “I can't explain it he Just 15" This was Nelson's idea of a pro- sald, “It | posal of marriage. i * ok E % { NJOW almost from the very firat she had known that, without com- | | 1 vou TrRoM ouT | YOUR IDEAL MATE COULD PICK, AND GAY OR OLD OR THICK? CONSUME THE MIDNIGHT QIL? OR WOULD HE ALTHO HE MIGHT IN-PANTS, MOON WAS OER YOUD WANT awake, in short, a live wire. “He must not be cruel-hearted—a man who will mistreat even a dog I could not love. “I should llke my husband to like all the things I like. I believe that our mutual likes draw us together. I do not believe In the old saying that opposites attract, unless perhaps in & physical sense. “My fdeal husband is not too domi- neering. He is willing to compromise l“ it is not a matter of principle. “He must love children and respect womanhood 80 much that it is im- possible for him to call his wife ‘old lady’ or her friends ‘old hens. “Lovers should talk over all affairs of life to see how much they have in common. The more interests in com- mon, the less chance for discord. They should see each other in every- day clothes and be honest in court- ship, concealing nothing that might influence either one's regard. “There should not be too much dif- nce in their ages. bove all, a woman wants & man who will never bore her.” * kR X HERE'S a ploture of one woman's ideal mate. Would she like him 1f she could find him in the flesh? ‘Would any of us like our “ideals” if we could have them for the asking? e prehending him, she liked him; and more than that, she had lately begun to feel that she understood him. She realized that the background of his life had been so heavily shadowed that he blinked and drew back, in- tuitively, trom the sun. She realized that behind his eyes, there was some- thing very significant: a matured emotion, wrapped in shyness. 'm going to miss you,” she sald, slowly. “I'm going to miss you a lot.” Nelson scowled ferociously at the stars. “Your {tineary's—hard and fast, is 1t “Oh, yes, Miss Wilkins has figured every minute.” T'll see ypu soon, though.” She shivered a little. “Is it half- past nine yet? I promised to walk with Freddie Dexter.” “Half-past nine exactl. son, and stood up. For the next forty-elght hours he played follow-the-leader, while Fred- dle Dexter led. If it were a matter of dancing, to the phonograph, Nel- son stood up and danced; his feet were uneducated in the modern steps, but he had rhythm and balance, and once he had been the show-pupll in his class. If it were a matter of hand-wrestling on the boat-deck, he dropped his coat and went into it like a schoolboy. ald Nel- On the last night he was singling, | by request, an old Harvard parody, | | birthday. when he suddenly awoke to the fact that Freddle Dexter wasn't there. Neither was Alice. and went away. * K ¥ X 'OW presently the fire opal went aft along the salon deck, and stood for a little while {n the moon- lige, looking out over the sea. She ‘was unaccountably lonely. Dexter, uncommonly grim, had just left her. As she gazed at the sea, and at the ars, she wished with all her soul that Nelson might have talked to her as Freddlie Dexter had been talk- Ing to her. If only he could express himself! If only she could know that he had something to express. At this moment, somebody began to play the plano in the salon At first she was scarcely aware of it, because the music fitted s0 per- fectly with the summer night. It was as though her own life, with all fts tumult and color and exaltation and sorrow, had been distilled into gracious notes. The incense of the east was burning in it, and she could see dimly, through the haze of in- cense, the prince and the princess in the fairy tale. And as it went on, dreamily, posses- sively, there were hot tears running down her cheeks; she knew, now, that Nelson himself was playing, there in the dark salon, and that he was play- ing what she had heard him play that first morning, a century ago. A man came briskly out of the salon, and halted. “I knew you were sald Nelson. “I knew ft. If I could only talk to you,” he said, hushed, “like that You didn't be- lleve me, but I did do it . . . I did it when I was eighteen; when there wasn't a person in the world I could talk to . 1t some- where—not in the geography-books at all—there only were a real seller THE RANKS OF MEN WOULD HE BE YOUNG AND GRAVE-~ OR THIN- WOULD HE, IN JOUTS OF JAZZSOME JOV. DEDICATE HIS TIME TO. PROFITABLE TOIL? ONE THING )5 SURE~ APPEAR A SAINT &, BEFOR~ THE HONEY- ANOTHER CHANCE! The chances are large and healthy that we wouldn’t. Have you ever noticed this curious thing about happiness—it never comes ready made. And it hardly ever arrives when we expect it. For instance, you are quite sure that if the morning were bright, your work done and you could go window-shop- ping until noon, you'd be radiantly happy. Then on some lucky day it happens that the morning is bright, your work done, and off you go. But do you find bliss waliting at the corner? You do not. Suddently your corn begins to hurt, the breeze blows dust In your eves, the windows prove to be fllled with utterly unin- teresting merchandise, you lose a nickel and the world is going to the dogs. On the other hand, in the midst of a hurried errand through fog and confusion, you'll find yourself filled with song! So it is with our theorizing about lovy ‘We think we'd be perfectly happy if we could find a certain kind of a man or woman. But we're mis- taken. In all probability we'd heartily despise him or her. For hap- piness in love Is not the result of a successtul stage setting. It's the re- sult of & successful combination. Do you remember your first experl- [ He got to his feet | | well BY HOLWORTHY HALL of real dreams, where you could go and buy whatever you want; what ever you've alw: wanted—why, maybe I'd have a chance . . . but I'm & tired-out, useless hulk— and I love you." ‘She reached out her hands to him passionately. “No, you're mot! No, you're not. Don't you dare to such a thing to me!" “Nor the rest of it, either? Don't you want me to talk to you? Don't you want me to try?” She lifted her eyes to him. all the reply he needed. She drew a very long breath. “T told you I was the luckiest person on the boat. I sald that even before I knew you. Because it was & miracle that T came at all. There wasn't one chance of it in a million. It was a present.” A present She nodded. It was “From an uncle of mine. You see, this party was planned last winter. They're all girls from the same school, and Miss Wil- kins was going to chaperon, and she asked if I couldn’'t go, too. And T couldn’t—we never could have af- forded it—and then the miracle hap- pened. There was a man that had owed my uncle some money for years and years, and, of course, he abso lutely never expected to see it again: and then right out of a clear sky it came in. It was last April, on my 1 just had a telegram from Messina to say I could have & thou- sand dollars. And that's how I'm here.” Nelson was staring at her. “Mes sina? T used to know Messina prett: myself. I lived there once . . . Have you spent much tim in Messina “I've never even been there.” “And is your uncle's name the same “No; it's Miller—Stewart Miller.” He continued to stare at her blankly. There was no possible doubt about it. He himself had actually, and for cash, bought Alice her dream. Except for his sacrifices to the mem- ory of his father, he would never have met her and loved her. Shehad told him that if he had as much as $5,000 a year it would be enough. He hadn't possessed the courage to tell her yet that he had $5,000 every fort- night. She had told him that if they might have a month in the Mediter- ranean she would be ideally hap She didn’'t know yet that if she the word she could live a lifetime there and in & palace of her own choosing. He was wondering, dazedly, it this were the time to begin all over again and to bewilder her with explana- tions or if it would be better to wait for a few weeks until she came to Paris, when she could see with her own eyes the magnificence of his offices in the Place Vendome, the beautiful villa which had been taken for him near the Bols, the glitter of the limousine which even now was resting deep in the Rochambeau's hold. “When you write to your uncle,” he said finally, “tell him you've met Ed- die Nelson, who used to work at the note desk in the Messina National Bank. I think he'll remember me—all right.” (Coprright, 1923.) WRITTEN AND ILLUSTRATED BY ) ELSIE TROBINSON ments in chemistry, when you found that H20 made water? Two parts ot hydrogen placed beside one part of oxygen did not make that water, wers the hidrogen and oxygen ever so pure and perfect. They had to be com- bined until the identity of both gases was lost—then, only, did water result. 8o it {s with marriage. To be truly happy we must lose much of ourselvea as well as find some one else. We must lose our prejudies, our fears, our self-consciousness. It is that loss which makes our happiness fully as much as anything the other one can give to us. * ok %k HE truth is that “there ain't no such animal” as an ideal mate, save in our dreams. He'd be as use- less as a nine-toed doodlebug it we did find him. And we only spoil our chances of realizing happiness with the friendly, common lads we know it we keep on searching for such superspouses. Be willing to combine—to amal- gamate—to lose some of your identity and accept sbme of the other chap's. Then almost any friendly biped who's willlng to 1augh over a joke and help wash the dinner dishes will prove your ideal mate. (Copyright, 1923.)