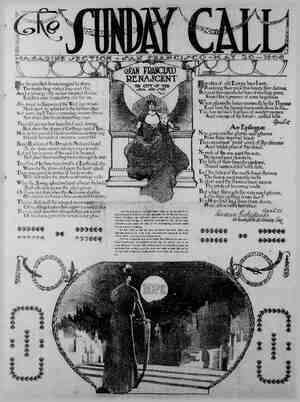

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, May 20, 1906, Page 12

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

THE SAN. FRANCISCO SUNDAY ' CALL IMAXTIM GORKRY'S LATEST WORKS - First Publication in English of the Strong Scenes in “The Children of the Sun” and “The Barbarians.” [T sty i ¥ rom "The Chi Pavel T‘yoaorovxon ! Zive him to me* one The scene slan drawing room Lize—You know how I a fear all that is coarse, and y me, as though to spite me! The locksmith call He is such a sus- rufloun Jooking men—and those large, of- 'ended eyes of his. It seems to me that I've seen them before—then—there—in the crowd. Chepurnoy—Eh, you had better not recall that! Leave him alone. Liza—Is it impossible to forget about 1t? Chepurnoy—What's the use of it? Lize—No flowers will ever grow on the epot where blood was shed. Chepurnoy—éand yet how they grow! Liza (Rises and begins to walk)—Noth- ing but hatred grows there. When I hear something coarse and harsh, when I see something red, & melancholy terror awakens in my soul, and my eyes imme- @ately behold that beastlike, dark mob, the blood-stained faces, the plashes of warm, red blood on the sand. And at my feet 1 see the youth with the fractured ekull. He i crewling somewhere; blood is pouring down his cheeks and his neck; he lifts his head toward the sky. I see his Qull eyes, his open mouth and his teeth. Hie head falls upon the sand, face downward. Chepurnoy—Eh, my God! Well, what Crepumy—ounn let us go into the gerden. Liza—Tell me—tell me, do you under- stand my terror? Chepurnoy—Of course I do. I understand 1t—1I feel it! Liza—No; that's not true! If you only understood it I would have feit relieved. 1 wish to cast off from my soul a part of the burden, and there is no other soul to take it—no Chepurnoy—] have observed everything and I have seen that life tructed miserably, that human be- ings are greeqy and stupid, and that I am wiser and better than they are. I was glad cnow th and my soul was at ease, I noticed that some human than that of the -a harder life than this was explained by more stupid than the t man horse ould you say this? You here I have come ee one consumed by nother dreaming e; a third pretending reasonable, and you have glim ;:ta somewhere into the depths v in your soul. re we spoiled you? his I cannot tell you. I company so much at first that vodka, for your But later 1 I began to feel un- what awk- mechanism of my become rusty. I feel the en of the SU Yoavl.s.e,a Iove the painter N1 S S e ] elania- I love, abnormal. n 1 must per- nd Vagin.) me tea for you? What can I do? Yelizaveta Fyodorovna. me. Oh, how you e world with moans! It is painful and “onsider it. What and I? fou had better be yes; it is beautiful, but in conception it is not profound, and the subject is not accessible to many. Vagin—Art has ever been the property he few. Therein lies the pride of art. Yelena—Therein lies her drama. ich is the opinion of the ma- Jority for this reason alone I am against it Yelena—Don’t pose! Art should ennoble mankind. Vagin—Art has no aims. Prota: My friend, there is nothing that is almless in the world Chepurnoy—Except the world Itself. Liza—My God! I have heard all this a thousand times. Yelena—Dmitry Sergeyevich! Iife 1is hard; man often grows tired of life. Life is rough, fe it not? On what is the soul to rest? Beauty is rare, but when I see something that is truly beautiful it warms my soul, like the sun that suddenly bright- ens a gloomy day. It is necessary that all mankind should understand and love the beautiful; then a moral would be con- structed upon it. The people would rate their action as beautiful and as ugly. And then life would be beautiful! Protasov—That's wonderful, Lena! Vagin—What have I to do with man- kind? I want to sing my song aloud, alone and for myself. Yelena—That will do! What's the use of your words? It is necessary that art should reflect man' eternal yearning the distance, toward the heights. ‘When there is such yearning in the artist, and when he has faith in the sunny pow- er of beauty, his painting, his book, his sonata would be clear to me, and dear, he would strike a harmonious chord in my soul. And if T grow tired I would take a rest and would again be eager for work, happiness and life! Protasov—That's capital, Lena! Yelena—Do you know, sometimes I pic- ture to myself a canvas like this: A steam- ship going in the middle of the boundless sea; green, angry waves embrace it greed- ily, and certain strong, mighty people stand by the sides on the Yore part of the ship. They simply stand there, their faces are open, brave and smiling proud- ly, they look far into the distance, ready to perish calmly on the road to their destination. That's the whole picture! Vagin—That's interesting. Yes. Protasov—Wait. Yelena—Let those people go under the sun on the yellow sand of the desert. Liza (involuntarily, in a low voice)—The sand is red. Yelena—That’s all the same! All that is necessary is that these should be extraor- dinary people, courageous and proud, un- shaken in their desires and simple even as all that is great is simple. Such a picture could make me feel proud of the people, of the artist who created them, and it would remind me of those great men who helped us to go so far away from the brute and who are forever leading us near- er to man. ¢ ¢ o Vagin—Yelena Nikolayevna! Somebody will stand alone on the forepart of the ship. His face will be that of a man who had buried all his hopes on the shore be- d him, but his eyes burn with the fire of a great tenacity, and he is on his way to create new hopes—alone amidst the lonely. Protasov—A stofm is not necessary. Or T8 U (RN A €I R AR AR » let there be a storm, but tue sun is shining in front of the ship. Call your painting oward the Sun,” the source of life! Vagin—Yes, toward the source of life. There in the distance, amid the clouds, will be the face of a woman, as bright s the sun. Protasov—Why a woman? But let there be a man like Darwin among the people on the steamship. However, I must go. (Goes out quickly.) Vagin (earnestly)—From day to day you are attracting me ever more firmly tow- ard you. Iam ready to pray to you. Yelena—Make no idol unto yourself, nor any other image. Vagin—I will paint this picture, you'll see! And its colors will sing 2 majestic hymn to Freedom, to Bcauty. o5 F T e R e Melania (earnestly)—You are a woman. you love, perhaps you will understand. Yelena—Not so loud. Your brother is in_the garden. Melania—What do I care? Now, listen. I love Pavel Fyodorovich. There! I love him so that I am ready to work for him as a cook, as a servant. You, I see, you love the painter. You don't need Pavel Fyodorovich. If you wish I will kneel be- fore you. Give him to me! I'll kiss your feet! Yelena (dumfounded)—What are you talking about? What's the matter with you? Melania—It's 2l the same. T have mon- ey. 1 would build a laboratory—a palace would I bulld for him! I would serve him so that no wind should touch him—I would sit by the doorway days and nights— that's what 1 would do! What do you need him for? While I love him as a saint—— Yelena—Compose yourself; wait! I am afraid I don’t understand you properly- Melania—Madam! You are a wise wo- man. You are a noble, pure woman. My life was so hard, so disgusting—I have seen only base people—and he! a child—he's so sublime! Beside him I would be a queen—to him a servant. to everybody else a queen! And my soul— my soul would breathe freely! I want a pure man! Do you understand me? There! Yelena (agitated)—It is difficult for me to understand you. We must talk it over at length. My God, how unfortunate you seem to be! Melania—Yes! Oh, yes! You can un- derstand me! You must understand me! That's why I speak to you like this—all at once. I know that you will understand me. Do not deceive me. also become a good woman if you will not deceive me! Yelena—I have no reason for deceiving He! He's * Perhaps T will” P MAXIME GORKY'S BIOGRAPHY 1868—Born in Nizhni Novgorod. 1878—Began to work as errand boy in shoe store. 1879—Apprentice In draughts- man’s office. 1880—Worked as kitchen boy on a steamer. 1883—Worked in cake bakery. 1884—Worked as wood sawyer. 1884—Worked as dock hand. 1885—Worked as baker. 1886—Chorist with small operatic company. 1887—Apple peddler. 1888—Attempted suicide. 1889—Rallroad guard. 1890—Secretary in lawyer’s office. 1891-—Began to tramp over Ru sia. Worked in a railroad shop. —Wrote his first story. 1884—His story “Chelkash” ap- peared in Viadimir Korol- enko’'s magazine, attracting much attention throughout Russia. Gorky has written five volumes of short storles; “Foma Gor- deyev,” “Troye,” -novels; “The Peasant,” an unfinished novel, and the following plays: “Mesh- chanye,” “On the Bottom,” “The Cottagers,” “The Children of the Sun” and “The Barbarian 1892 owm0~ PEPIEIIIE0000000000040000000000000000000000 f | ! you. I feel your suffering heart. Come to me! Come! Melanla—How you speak! that you are also good? Yelena (taking her by the hand)—Be- lieve me, believe me, if people will only be sincere they will understand one an- other. Melania (following her)—I do not Know whether I believe you or not. Your words I understand, but I cannot understand your feélings—whether you are good or not. T am afraid to trust in the good. I have never seen it, and I am myself a bad, x‘nomnt woman. I have washed my soul Is it possible with a sea of tears, but it is still dark. B e T S ey e e e Liza (nervously)—I am telling you, the earth is being piled ap evermore witl hatred.. Cruelty is growing on earth. Protasov—Liza, are you again spread- ing out your black wings? Liza—Don’t say that, Pavel. You sec nothing, you are looking into a micro- scope. Chepurnoy—And you—into a telescope’ You should not do it, you had better look with your own eyes. Liza (with anxiety)—You are all blind Open your eyes! That by which you live your thoughts, your feelings, are like flowers in a forest filled with darkness and decay, filled with horror. There are only few of you; you are not noticed on earth. Vagin (dryly)—Whom do you see on earth, then? Liza—The millions are noticed on earth, not the hundreds—and amidst the mil- lions hatred s growing. You, intoxicated by words and thoughts, do not see this, but I saw how hatred poured forth into the street and the people, infuriated, en- raged, destroyed one another with pleas- ure. ‘Some day their wrath will fall upon you. * * Protasov—Fear of death—this hinders people from being brave, beautiful, free! This fear hangs over them like a black cloud; it covers the earth with shadows and brings forth apparitions. It forces them to stray aside from the straight 10ad toward freedom, from the wide road of experience. It impels them to form hasty, abnormal conceits of the meaning of life; it frightens reason and then thought ¢ ates-delusions! But we, we human being;: children of the sun, we will conguer the dark fear of death! We are the chiliren of the sun! It is the sun that is Lurning in our blood, it is the sun that brings forth proud, flery thoughts, illum‘n.ating the darkness of our doubts; th2 sun is an ocean of energy of be.:uty and of soul in- toxicating” joy! * Liza—You lied, Pa\‘elY Life 15 full of brutes! Why do you speak of the inys of the future? Why do you decelve your- #elves and others? You have le(t man Yar_behind you—you lonely. unfortunate. small people. Is it possible that you do not understand the terror of this Lfe? You ‘are surrounded by enemies—cvery- where brutes! It is necessary to destroy cruelty, to conquer hatred. Understand me! Understand me! (Hysterics.) Curtain. “The Barbarians” is a keen 2xposura of the life and morals of the Russian so- called “Intellectuals.” The following ex- tracts are from the lasl act. The scene CLEVER TRICKS The time for little dinner table tricks is after the dessert is passed and when cordials, bonbons and cigarettes are mak- ing their way around the table. Then the ingenious person starts up some bit of foolishness and is eugerly followed 1 - others present. An old but amusing din- ner table trick is to we: the middle finger and then pass it slowly around the top of the finger bowl. { A long drawn out musical note is the r&ult. varying greatly in tone. From each finger bowl that is played on comes-a different note. Some are high and shrill, others low and dron- ing. The combined harmony produced by several finger bowl notes together is often very curious. While the finger bowis are ringing the shells of English walnuts are separated in halves and made into little barges to float on._the water. Usually they are propelled along with silver nut picks, and when the trick is most exciting they are filled. with brandy and set on fire that they may represent burning ships at sea. ‘Where brandy is used in connection with mandarin skins the purpose is quite different. It is there to make a cordial ‘which may be sipped at leisure. The skin of the mandarin is deeply cut around t.he FOR AFTER-DINNER AMUSEMENT fruit'’s middle and each half then laid back ‘until it is peeled off and appears like a small cup, the skin itself being turned inside out. 'Into the cup abgut two tablespoonfuls of brandy are poured and set on fire. As it burns it draws out the pungent ofl in the mandarin skin and forms a cordial like curacoa. The fragrance of the fruit while the brandy is burning is delightful. Thy lqueur thus formed, however, . is ‘very strong, and can only be taken by tue hardy in any but very small ‘When creme de menthe cordia] it is thought amusing to blow cigarette smoke over the top of it—that is to try and make the smoke flll the space between the .creme de menthe and the top of the glass. This is not easy to do, as the slightest movement of air. blows the smoke away. The smoke must be puffed very slowly into the glass that it may settle, and the one doing this trick. must then draw his head away sidewise 80 that no upward movement of air is created. . The color effect of the smoke as it rests on the emerald green of this cordial is mystic and beautiful. It also is so light that it can be blown off wmmut affecting the taste of the liqeu A number of ‘perso: dinner table trick przzent often a comical scerie, owing to the various positions they take w0 prevent moving the smoke. It is a trick, however, which invariably delights the artistic. To mold a pig from bread crumbs is another amusement of those that linger late at the table. . It brings out consider- able nimbleness of fingers and shows clearly which ones at the table have a lurking talent for sculpture. Those who make the pigs most successfully first make the bread into a compact oval shape about an inch long. It is then by inden- tations and modelin with the finger tips that the legs and head and even the curlicue tail of the pig gradually appear. Besides these table tricks there is an- other of making red wine rest on the top of water In'a colored stratum. The wine is lighter than the water, but unless it is manipulated very carefully the force with ‘which it is poured on the water will make it break through and sink to the bottom. The method, therefore, is to use a tea- spoon, Into which the red wine is taken and: then alowed to trickle very slowly down the side of the glass and float out over ‘water. This slow process is con- tinue the wine's pathway down the side fl? thfl ghu not being allowed to broaden to the helght desired. FINDS THE MUSIC OF AN EARLY INDIAN MELODY An interesting relic of the first genu- ine’ Indian melody has just been discov- ered by Abraham Holzmann, an Ameri- can musician, who is setting it into mod- ern dress. The curlo was found recently in an old bookshop in Oklahoma and bears the imprint of 1809, nearly a century ago. 1t is printed, or, painted, upon vellum, ‘and, although stained and tattered, is plainly legible in The: musical parchment is. & curlosity in that it bears all 29 essential notations of modern music— po. .cefs, staves, rests, etc., as embodfed in the’ ta- &on nlhzd also :lo Fgmnucu::uly 'I‘;I; e firet musical I re adopted . b the Indian. mfit‘e nm ‘Muskoges, In. dian ‘ Terr| 1 b: i k:mmw ounfled v the Chero- Professor Holzrhann, who' possesses the. Mn:mt, IM whavu himselt a/com-' ‘a8 the poser, vlfl{ written such works as "Yllxk“ Girl, American compositions, says that he believes the work was originally con- structed' by. some Indian tutor, inasmuch “Flying Arrow" plece comprises a tion of melody and adapted the opening movament and be- 7es he can evolve a wwo-step from the x::‘k. ‘whi¢h will bear modern orchestra- e et e e 1 e e W £ Ty USRI S A 0> f‘rom T}w Earbanan ‘Give takes place in a garden in a small provin- cial town: Cherkun (placing his hands on her shoulders).—Do you love me? Yes? Well, tell me, do you love me? Monakhova (in a low voice, firmly)— Yes! As soon as I saw you—at once. My George! You are my George! (She em- braces him.) Enter Anna (Cherkun's wife), her face tear stained, a handker- chief in her hand. Noticing her husband and Nadyezhda Monakhova, she straight- ens herself. Anna (in a low voice)—This is nasty! Cherkun (with a drunken smile)—Don’t be in a hurry, Anna—although—it makes no difference— Nadyezhda—TYes. same. Anna (with dlsgusty—Oh, you are a brute! You are a nasty brute— Nadyezhda (coolly)—That's because I love him? Now it is all the Cherkun (as though aroused from sleep)—Wait, Anna, be silent— Anna—You want me to be silent? Oh, how low you have fallen—I could under- stand it if it weren’t this one—If it were some one else—but this woman! This is a brute— Nadyezhda (to Cherkun)—Come George. Cherkun—Nadyezhda Polikarpovna, lis- ten) a noise in the corridor. Tsiganov runs in, followed by the doctor and Monakhov, Nadyezhda's husband)- Tsiganov—Bring this blockhead to his senses. He has spoiled my finger- Doctor (holding a large, old revolver. Leaning against the doorpost with one arm, he aims the revorver at Tsiganov)— I'll spoil 'you all. (Lets the cock go. Misses fire). Tsiganov—Ass! You can’t shoot! Cherkun (rushing over to the doctor)— Drop it! Anna and Nadyezhda (together)—Go He'll kill you! Doctor (turning the revolver with his fingers)—Be cursed, you devil— Nadyezhda (tearing the revolver from his_hands)—Oh, you fool! Cherkun—Have you lost your reason? Monakhov—Hadya—he'll kill— Lydia (running in)—What has hap- pened? Tsiganov—I have enough of my own sins—I don’t want to pay for those of others—you savage! Anna (to Lydia)—He xissed her—her! (to Monakhov.) Take away from here this—— (to Lydia) They were kissing each other— Lyvdia (leading her away)—Stepa, call auntie over here— Doctor (to Cherkun, in a dull voice)— Kissing him? You? Cherkun—Get away from here—— Tsiganov (tying a handkerchief around the hand)—He woke up—the idiot! Doctor (plaintively)—Nadyezhda! Whom hast thou chosen? Nadyezhda (regards him with a smile)— Don’t say “‘thou™ to me. Doctor—Whom hast thou chosen? Nadyezhda (pointing at Cherkun, proud- 1y)—Him! Monakhov—Nadya! Nadya! What for? What wrong have I done, Nadyusha? Bogayevskaya (coming in)—What, scandal? We have come to it to_Anna's room)! Doctor (to Tsiganov)—You, sir! T beg your pardon. I should have shot him. But then, it is all the same! You are both birds of prey. Iam sorry that I have not killed you. I am very sorry. Nadyezhda (ngret!ully)—-whxt can you a (passes do. Eh, you! Doctor—That's right! I can't do any- thing! Everything has been consumed within my soul. You have barnt it! Cherkun—Well, that's enough, I say! Monakhov—Nadya, let's go home. Nadyezhda (firmly)—My home is where his is—that’s where my home is! Doctor—My heart was burning for four long years— Tsiganov—Yégor! What is he it about? He tore my R natl— Cherkun (to m doctor)—You have pald me back oy wi %ole. fc?fiel_ 1gave qn my life ts her cheaply for your prank—go! That will do! Doctor (coming to himself, simply)— Goodby, Nadyezhda! I love thee. For- glve me—for everything! Goodby. Thou will be ruined with them—thou wilt be ruined! Goodby! Goodby, all—you crows (goes out). ° Tsiganov (to Nadyezlida)—Well, are you satisfled at last? All has turned out as in a novel—happy love, three people unfor- tunate—an attempt to shoot—biood (points to his finger, which is covered with a handkerchief). Is it good? Nadyezhda (dully)—What will he do now—also commit suicide? Tsiganov—I would have shot myself—for shame. Monakhov (to Cherkun in a low voice)— Give me back my wife! Give her to me. I have nothing eise. She's my all. T gave all my life to her. I stole for her— Cherkun (harshly)—Please, take her! Nadyezhda (astonished, to Cherkun)— What did you say? Take her? Yes? Cherkun (firmly)—Yes! Nadyezhda. 1 ask you, forgive me Nadyezhda—What? Cherkun—Don't attach any significance to my act. A momentary impulse— aroused by yourself—that's not love in the full sense. Nadyezhda (In a dull voice)—Speak more plainly, so I can easily understand. Cherkun—I do not love you—No! Nadyezhda (not belleving) That can't be! You have kissed me—nobody has ever kissed me, nobody but you! Monakhov (meekly)—And I—and 17 Nadyezhda—Be silent, corpse! Cherkun—Let us put an end to all thi Did you understand me? Forgive me -if you can! (About - go.) Nadyezhda—No. no! I will sit down George, sit down near me, won't you— Yegor “Petrovich. Cherkun—I do not love you— love you! (Exit.) 3 ¥ Lydia—I have sought for a s firm man whom I could respect!::d;:"'n sought for a long time—I am seeking for a man that I could adore, to go with him, side by side. Perhaps this is omly & dream. But I will contt e ntinue to seek for Cherkun (softly)—To worshi; ? Lydia—And to go with him .&gmb-i stde. Are there no sages among men on earth? Are there no heroes, to whom life is a great creative work? Is it possible that there is none? Cherkun (softly. in despai pair)—It is - possible to preserve one’s self here, !’J:- It is impossible. The pow- derstand me. er ordthls life—of this filth— Lydia (angrily)—Everywhere ititul people, everywhere greedy peovlo——’ shot is hard from the yard.) 18 Cherkun (sadly)—Oh, again! What's (rushing out from her room)-— there again? Anna Yegor! Where? Oh! You are here! God! (Sinks down on the couch. ) b Lydia (going out)—I'll see—— Bogayevskaya—And I was about to go to_bed already. Yes— Tsiganov (in the corri red” Cherkun—Who fireas | " D0t So— Tsiganov (pal )-sn hda Cherkun—At ‘. e Tsiganov ‘lhudderh\g)-—,\t B - my presence—in the presen-e o('r.:"h__ bln.ml~m coolly—plainly—the devil take Bogayevskaya (goes to the corridor). What a feol! Whe coul o thought of it? oo Anna .rushing over to her hu e Yegor, you are not to blame! No, .?0:::— Lherkun—whp"e—il—tlut-docwr" Monakhov (entering)—The doctor is not ge:d;‘-d There's no need for anything now. ntlemea, you have kil uman ing—what for? Tiie s Anna—oh, Yegor—not you—not i you! Monakhov (softly. with horror What have you done? b e done? (All maintain silence. ho(c:“m howling outside.) /